The Ainu (or “Utari”) people are a group of people indigenous to the island of Hokkaido, the northernmost island of Japan. Though just recently recognized officially by the Japanese government, it is clear that the Ainu people have existed for at least a thousand years, maintaining a culture and ethnicity distinct from that of the Japanese.

In the early 20th century, the Ainu people grabbed the attention of many anthropologists when it was publicized that they shared physical and skeletal features with the Caucasoid typology (yes, this is a legitimate term in physical anthropology – it was misappropriated by the pseudo-scientific racists and eugenicists in the 19th and 20th century, but anthropologists agree that there do exist measureable differences in the bodies of people in different ‘racial’ categories.)

While the theory that the Ainu were unrelated to the Japanese has recently been debunked by genetic studies, it persisted for many years, and captured the imaginations of many who studied ancient human migration patterns. Some of the more eurocentric westerners were interested in studying their culture to see any potential connections between the Ainu and other caucasian peoples.

They emphasized differences between the Ainu and the Japanese in language, stature, customs, skin shade, and particularly, in their appearences, which were shocking to the fastidiously-groomed Victorians. Ainu people of both sexes had long and untamed hair, the men wore long beards and moustaches, and the women had tattoos around their mouths which westerners likened to “women’s moustaches“. The 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica entry on the Ainu states confidently: “Uncleanliness is characteristic of the Ainu, and all their intercourse with the Japanese has not improved them in that respect.” It was additionally shocking to the westerners that the Ainu raised bear cubs in their houses, like pets, and then sacrificed the full-grown bears once a year, and set their skulls up in family shrines.

Given all of this rhetoric, and the colonial relationship between the Japanese government and the Ainu peoples, it is not surprising that the culture was not well studied for many

years. In 1900, however, a traveler from Philadelphia, Hiram Hiller, took a detour from his pan-Asian journeys (yet another amazing archives story) to visit Hokkaido. He met Jenichiro Oyabe, a Japanese man who was educated as a missionary at Yale University and Howard University.

Oyabe served as a translator and a guide to the Ainu people, and consequently Hiller

amassed a large collection of the objects of daily life. The Penn Museum’s collection is one of the largest in any museum, so much so that the The Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture (FRPAC) recently borrowed almost all of our collection to display in the Ainu Craft Exhibition 2008 at Niigata Prefectural Museum of History in Nagaoka City, Japan.

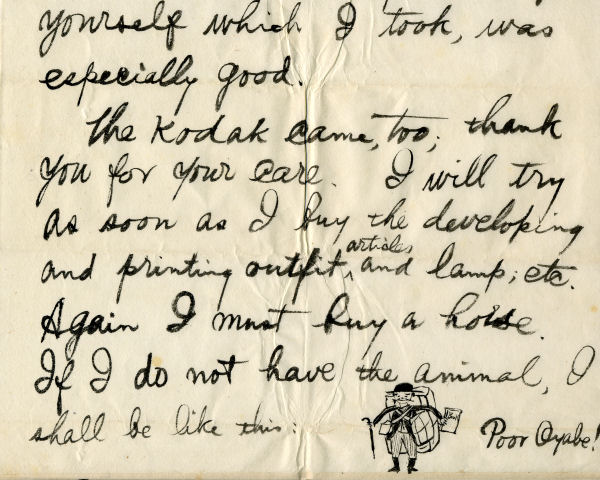

Once Hiller returned home, he stayed in contact with Oyabe, who wrote him friendly letters encouraging him to “tell the world about my beloved Ainu people”. Which brings us, finally, to our Fun Friday Image – a scan of a (small!) section of a letter from Oyabe to Hiller, in 1902. This letter is written on calligraphy paper, and the entire piece is about 11 inches wide by THREE FEET long! I love this letter for many reasons, but particularly because it illustrates the problems of early photography, and reminds us of the difficulty that our forefathers went through to bring us the images we now appreciate. It is also an excellent expression of Oyabe’s personality and sense of humor, and makes me wish he were alive to be my pen pal now.

The text of the letter: “…the picture of yourself which I took, was especially good. The kodak came too; thank you for your care. I will try as soon as I buy the developing and printing outfit, articles, and lamp; etc. Again I must buy a horse. If I do not have the animal, I shall be like this: [drawing of a man with many backpacks and parcels, holding an umbrella and a piece of paper] Poor Oyabe!”

I hope Oyabe got his horse. It’s only fair, in return for the work he did for Hiller, the Penn Museum, and for his beloved Ainu.

…………………………………………………………..

Many more references:

The Smithsonian Institution’s Excellent Website for their 1999 exhibit: Ainu – Spirit of a Northern People

– also make sure to read Adria Katz’s article “An Enthusiastic Quest: Hiram Hiller and Jenichiro Oyabe in Hokkaido 1901.” in the exhibit catalog

The Ainu Museum of Japan

Early European Writings on Ainu Culture By Kirsten Refsing

Oyabe’s Autobiography, “A Japanese Robinson Crusoe”

Jenichiro Oyabe’s collection of Ainu Riddles

A Japanese perspective on the Ainu recognition by the Japanese government

“Island of the Spirits” a website for the NOVA documentary about Hokkaido

An interesting article on the Japanese practice of Ainu-e paintings, which show a great deal of indigenous life since the mid-19th-century