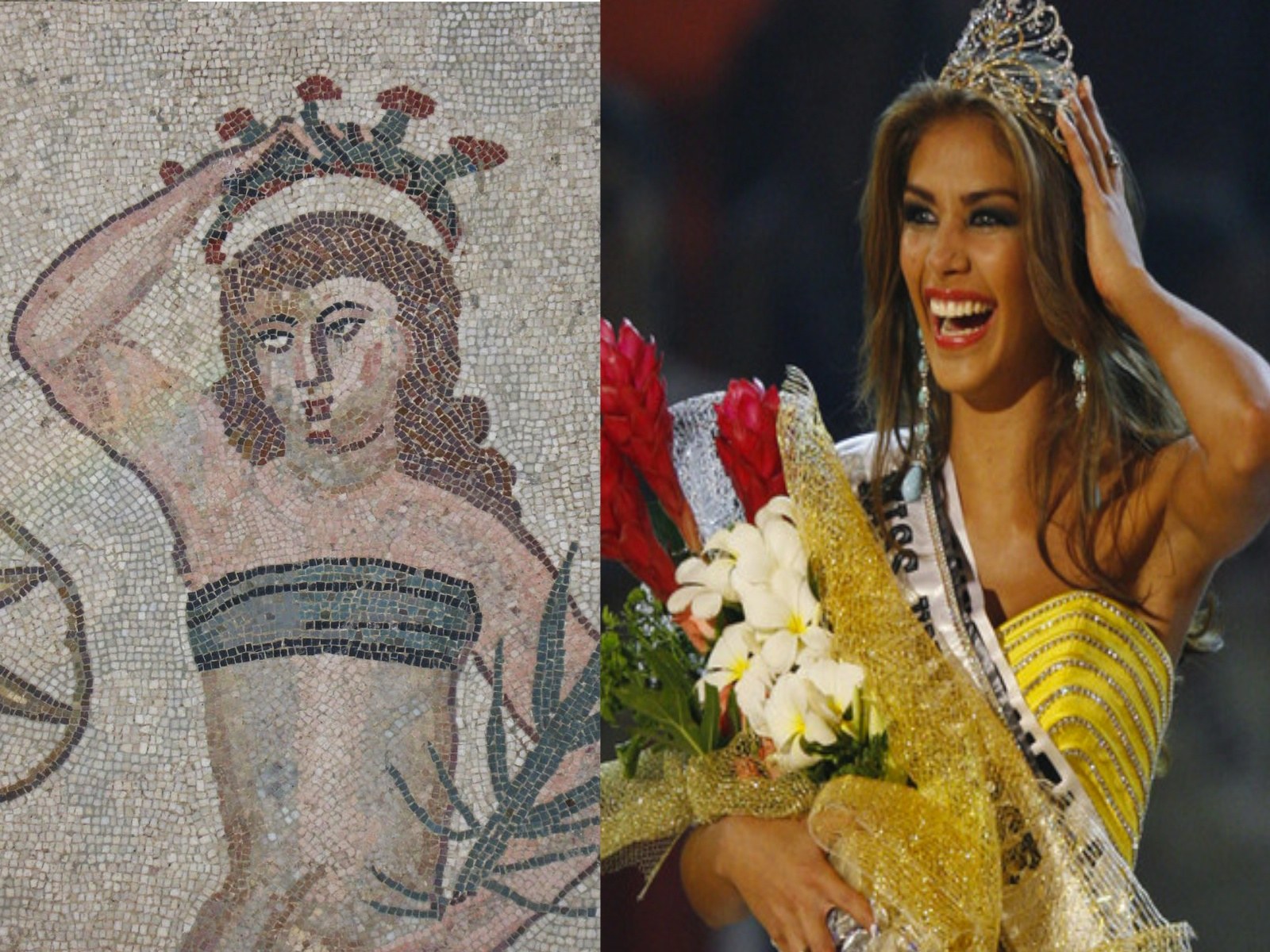

The Villa del Casale of Piazza Armerina is the 4th-5th century Roman villa that is the subject of an article of the same name by Patrizio Pensabene and Enrico Gallocchio in the 2011 summer edition of the Penn Museum’s Expedition magazine. A UNESCO World Heritage site, the villa boasts architectural remains, archaeological remains, and, most famously, extensive mosaics and frescoes that reveal aspects of economic and social practices of the late Roman Empire. Featured on the cover of the summer 2011 Expedition magazine is a detail showing two figures from the villa’s famous mosaic, “Bikini Girls,” but inside is a picture showing nine of the Bikini Girls. Only the legs of a tenth remain in the top left corner where the geometric design of another mosaic is visible from underneath. The women are arranged in two rows of five and clad in what look like a modern day two-piece bikini swim-suits. As the article briefly mentions, the women were originally thought to be contestants in a beauty competition; the center figure on the lower row, holding her hand to her crown-like headpiece while cradling a frond of some sort, does seem to be the Roman progenitor of Donald Trump’s modern-day Miss Universe. This interpretation has since been invalidated.

Today, the women are believed to be participants in an athletic competition. Upper-class women in the Roman empire were granted some personal freedoms in the realms of entertainment and leisure, often frequenting bathhouses, racetracks, theaters, and even gladiator stadia with their husbands. In fact, much was written in the early Roman empire on the female proclivity for ancient Rome’s most notorious athlete, the gladiator. Juvenal in the 1st century CE derides women’s excessive attraction to gladiators when he writes in his Satires,

“There are lots of ugly things on his face, like a huge wart on the middle of his nose, right where the helmet rubs it, and foul stuff always dripping from his eyes. But he was a gladiator. That makes him a Hyacinth; for that, she prefers him to her sons, her country, her sister, and her husband. It’s the sword that they love.”[1]

Perhaps it then comes as no surprise that women as gladiators themselves were very much frowned upon. “What decency can a woman show wearing a helmet, when she leaves her own sex behind?”,[2] Juvenal continues in the same Satires 6 on women’s faults. Nevertheless, the concept of women competing in more “feminine” sports, like ball tossing and discus throwing, was apparently celebrated among the social elite, as it is depicted and validated by this mosaic. It is especially interesting to note that villas were often constructed to offer important, high-ranking urbanites a reprieve from city life and that luxury residences in ancient Rome were not only private homes, but were also used as public spaces. So, while many questions still remain for me as to the cultural and historical significance of this mosaic, it is exciting to see a representation of female independence and athletic prowess (although as a subject of the male gaze) lauded on the walls of a socially significant, male-oriented space.

[1] Mahoney, Anne “Roman Sports and Spectacles: A Source Book.” Newport, Massachusetts: Focus Publishing, 2001. Accessed Online (August 12, 2011): http://www.pullins.com/BookViews/BV1585100099.pdf

[2] Mahoney (p67)