By Tessa Young and Jen Mikes

Conservators love gold! Not only can it be worked with ease through a variety of processes to make beautiful artwork and jewelry, but it also never tarnishes or corrodes…not in 50 years or 5000 years – NEVER! When Queen Puabi’s headdress (ca. 2450 BCE) was excavated in the 1920s by Sir Leonard Woolley, her golden adornments were gleaming just as brightly as ever. You can learn more about Queen Puabi and her amazing treatment history here, and in the new Middle East Galleries.

Left: In situ image of the headdress of Queen Puabi, excavated by Leonard Woolley in the 1920s. Right: Puabi’s headdress on display in the new Middle East Galleries.

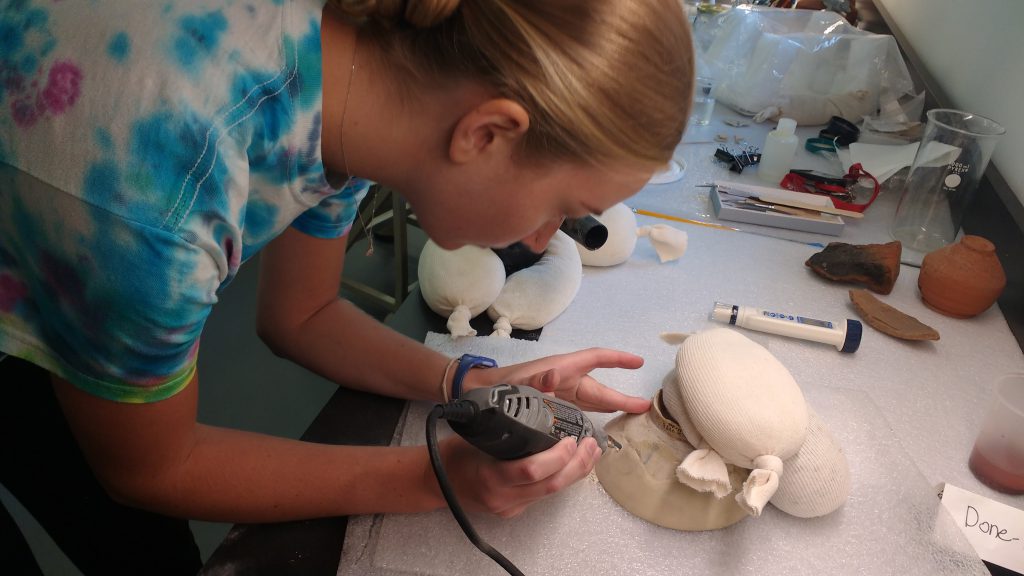

In the past few weeks, the Conservation Lab has been shimmering with gold. Williams Project Conservator Alexis North is preparing for the upcoming Mexico and Central America Gallery, treating gold pendants and ornaments. As a material, gold has virtually no inherent vices: it will not deform or crack with changes in relative humidity or temperature, nor will it discolor with age or UV exposure… it’s as stable a material as a conservator could ask for! According to the American Institute for Conservation’s Wiki gold entry, “Under normal conditions, [ ] gold is incredibly stable and is more often susceptible to damage from mechanical pressures (scratching, distortion, etc.) rather than corrosion and other chemical processes.” Since conservators spend considerable amounts of time preventing and treating corrosion of less stable metals, the chance to work with largely inert gold objects is very exciting.

Gold frog ornament, SA2902, with a mend on its back proper right foot. https://www.penn.museum/collections/object/253831

Despite it’s notorious stability, each gold object was carefully documented and assessed for condition issues, as with everything that comes through the conservation labs. For most gold objects, the only treatment necessary is a brief campaign of degreasing with ethanol on cotton swabs. For others with thin and pliable areas, such as the back right foot of the golden frog ornament pictured above, external forces exerted on the material may cause stress cracks, potentially culminating in a break. Where cracks are seen, mends with toned Japanese tissue may be applied, creating inconspicuous band-aid-like fixes. After these quick treatments, the objects can often be returned to storage by the end of the day.

However, not all that glitters is entirely gold. Because gold is such a soft and expensive material, many “gold” objects are composed primarily of a harder and less expensive metal with just a thin layer of gold at their surface. There are several processes used to achieve this look. A number of the gold objects in the upcoming Mexico and Central America Gallery, including the golden frog ornament above, were manufactured using the technique of depletion gilding. Additional methods of gilding may be used to adorn metal or wood surfaces such as water gilding, oil gilding, acrylic gilding, or mercury gilding.

Another method for achieving the look of gold while reducing the cost or fragility, is by creating alloys (mixtures) of gold and other metals; a common example is white gold, which is composed of gold and nickel, palladium, platinum, and manganese. The inclusion of other metals in a gold alloy alters the properties of the gold, and may increase the hardness of the final material. However, the presence of non-gold metals in an alloy will predispose the material to tarnishing and discoloration.

To learn more about gold in Central America, check out this piece from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.