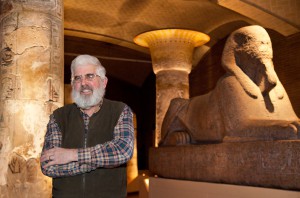

- Patrick McGovern is the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, where he is also an Adjunct Professor of Anthropology. In the popular imagination, he is known as the "Indiana Jones of Ancient Ales, Wines, and Extreme Beverages." Read more

Caption: “Dr. Pat” in the Lower Egyptian Gallery of the Penn Museum, with the largest sphinx in the Western hemisphere to his side and columns of the 13th c. B.C. Merenptah palace behind him. Photo by Alison Dunlap.

Ancient Brews Rediscovered and Re-Created

The Foreign Relations of the “Hyksos”

-

Earliest Known Eurasian Grape Wine Discovered!

In the News An 8,000-Year-Old Vintage! Penn Museum Researcher Confirms Earliest Known Evidence of Grape Wine and Viticulture in the World Penn Museum researcher Dr. Patrick McGovern, Scientific Director of […]

-

Lectures and Tastings

March 9, 2024: Lecture on ancient wine and tasting of retsina and Amarone for New Jersey Classical Associaton, Pennsauken Country Club, NJ. Nov. 16, 2023: keynote address for Ghvino VI, […]

-

Intoxicating: The Science of Alcohol

Alcohol or ethanol has long perplexed our species. Wherever we look in the ancient or modern world, humans have shown remarkable ingenuity in […]

-

Beginning of Winemaking in France

New Evidence on Origins of Winemaking in France New BIOMOLECULAR aRCHAEOLOGICAL Evidence Points to the Beginnings of Viniculture in France * * * 9,000 Year Old Ancient Near Eastern “Wine […]

-

Biomolecular Archaeological Evidence for Nordic “Grog” and Expansion of Wine Trade Discovered in Ancient Scandinavia!

Discovery Highlights Innovative and Complex Fermented Beverages of Northernmost Europe in the Bronze and Iron Ages Philadelphia, PA 2014—Winters in Scandinavia were long and cold in the Bronze and Iron […]

-

Dig, Drink, and Be Merry

In the lab, a flask of coffee-colored liquid bubbles on a hot plate. It contains tiny fragments from an ancient Etruscan amphora found at the French dig McGovern had just […]

![Earliest Known Eurasian Grape Wine Discovered! In the News An 8,000-Year-Old Vintage! Penn Museum Researcher Confirms Earliest Known Evidence of Grape Wine and Viticulture in the World Penn Museum researcher Dr. Patrick McGovern, Scientific Director of […]](https://www.biomolecular-archaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/GadachriliOverheadDroneDJI_0487-640x300.jpg)

![Lectures and Tastings March 9, 2024: Lecture on ancient wine and tasting of retsina and Amarone for New Jersey Classical Associaton, Pennsauken Country Club, NJ. Nov. 16, 2023: keynote address for Ghvino VI, […]](https://www.biomolecular-archaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/cheers_to_science_a_drinkable_feast_of_beer_biotechnology_and_archaeology-373x230lecture.jpg)

![Intoxicating: The Science of Alcohol Alcohol or ethanol has long perplexed our species. Wherever we look in the ancient or modern world, humans have shown remarkable ingenuity in […]](https://www.biomolecular-archaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Cover-640x300.jpg)

![Beginning of Winemaking in France New Evidence on Origins of Winemaking in France New BIOMOLECULAR aRCHAEOLOGICAL Evidence Points to the Beginnings of Viniculture in France * * * 9,000 Year Old Ancient Near Eastern “Wine […]](https://www.biomolecular-archaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/PNASLattesFig3press-640x300.jpg)

![Biomolecular Archaeological Evidence for Nordic “Grog” and Expansion of Wine Trade Discovered in Ancient Scandinavia! Discovery Highlights Innovative and Complex Fermented Beverages of Northernmost Europe in the Bronze and Iron Ages Philadelphia, PA 2014—Winters in Scandinavia were long and cold in the Bronze and Iron […]](https://www.biomolecular-archaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Fig3Havorhoard-640x300.jpg)

![Dig, Drink, and Be Merry In the lab, a flask of coffee-colored liquid bubbles on a hot plate. It contains tiny fragments from an ancient Etruscan amphora found at the French dig McGovern had just […]](https://www.biomolecular-archaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/smithsonian_article1.jpg)

![Earliest Known Eurasian Grape Wine Discovered! In the News An 8,000-Year-Old Vintage! Penn Museum Researcher Confirms Earliest Known Evidence of Grape Wine and Viticulture in the World Penn Museum researcher Dr. Patrick McGovern, Scientific Director of […]](https://www.biomolecular-archaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/GadachriliOverheadDroneDJI_0487-195x110.jpg)

![Lectures and Tastings March 9, 2024: Lecture on ancient wine and tasting of retsina and Amarone for New Jersey Classical Associaton, Pennsauken Country Club, NJ. Nov. 16, 2023: keynote address for Ghvino VI, […]](https://www.biomolecular-archaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/cheers_to_science_a_drinkable_feast_of_beer_biotechnology_and_archaeology-373x230lecture-195x110.jpg)

![Intoxicating: The Science of Alcohol Alcohol or ethanol has long perplexed our species. Wherever we look in the ancient or modern world, humans have shown remarkable ingenuity in […]](https://www.biomolecular-archaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Cover-195x110.jpg)

![Beginning of Winemaking in France New Evidence on Origins of Winemaking in France New BIOMOLECULAR aRCHAEOLOGICAL Evidence Points to the Beginnings of Viniculture in France * * * 9,000 Year Old Ancient Near Eastern “Wine […]](https://www.biomolecular-archaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/PNASLattesFig3press-195x110.jpg)

![Biomolecular Archaeological Evidence for Nordic “Grog” and Expansion of Wine Trade Discovered in Ancient Scandinavia! Discovery Highlights Innovative and Complex Fermented Beverages of Northernmost Europe in the Bronze and Iron Ages Philadelphia, PA 2014—Winters in Scandinavia were long and cold in the Bronze and Iron […]](https://www.biomolecular-archaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Fig3Havorhoard-195x110.jpg)

![Dig, Drink, and Be Merry In the lab, a flask of coffee-colored liquid bubbles on a hot plate. It contains tiny fragments from an ancient Etruscan amphora found at the French dig McGovern had just […]](https://www.biomolecular-archaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/smithsonian_article1-195x110.jpg)