Introduction

“Do not reproach someone older than you, for he has seen the Sun before you.”

The Instruction of Amenemope, ca. 1400 B.C.

The story of Egyptology at the University Museum is fundamentally that of the men and women who for over 80 years staffed the Egyptian Section and were responsible for the major contributions that section has made to our understanding of ancient Egypt. Some of these people, such as Rudolf Anthes, Henry Fischer and other Egyptian Section staff members of recent years are happily still alive and vigorous. The others are at least partly revealed to us in hundreds of letters preserved in the Museum archives and in the published reminiscences of themselves and their contemporaries. They varied greatly in character and personality; they had their successes and their failures, their virtues and their follies, and all of these will emerge in the course of this article. But basically the record is one of outstanding achievement, a record that challenges us, their successors, to equal, let alone surpass our predecessors; with respect and affection we dedicate this memoir to them.

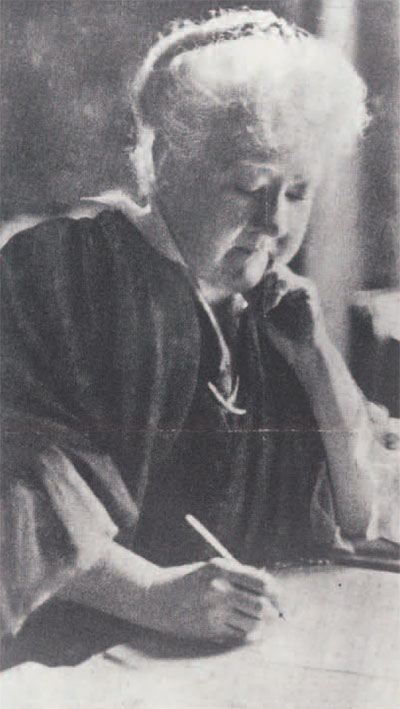

Nothing could more appropriately introduce our story than the visit of Sara Yorke Stevenson, first curator of the Egyptian Section, to Cairo in 1898. This shrewd and vigorous Philadelphia lady immediately set about trying to organize the University Museum’s first Egyptian field project. The task was a formidable one and Mrs. Stevenson’s experiences were very different from those of the many well-off tourists who flocked to Egypt at that lime. As John Wilson made vividly clear, they found a trip to Egypt ‘an easy and fascinating way to see the East.’

“From Shepheard’s [a famous hotel in Cairo, ‘with a vivid decor in pseudo-pharaonic style] famous terrace, over a coffee or a lemon squash, one could sit idly and watch the teeming throng sweep past: Egyptians in from the villages returning one’s stares openly, barefooted Nubians of great dignity, two-wheeled donkey carts, and then shouts and a rumble as an open landau carrying some fat Turkish dignitary in a red tarbush careened past, preceded by running saises who cleared the way with sticks. Veiled ladies rode by, fiercely guarded by eunuchs. A diplomatic carriage would have a fiercely moustached kavass mounted beside the driver and clothed in brilliant costume and carrying a curved saber and staff as insignia of his master’s ‘sublimity.’ ” Those tourists who tired of Cairo could sail upstream in comfortably appointed sailing house-boats or steamers and visit the tombs and temples of ancient Egypt and the picturesque native villages beside them. (John Wilson, Signs and Wonders upon Pharaoh. A History of American Egyptology, 72-74.)

Mrs. Stevenson had little opportunity to enjoy this leisurely life. The Egyptian government at this time was controlled by a British consul-general and Egyptological affairs were the responsibility of British, French and other foreign scholars and bureaucrats. Her commission was to deal with these gentlemen, who represented different, often competitive national factions and were often on bad terms with each other. Mrs. Stevenson soon made a forthright assessment of the situation. “I never in my life saw such intriguing,” she wrote. “Politics-science-personal rancor is all mixed up.” Her chosen agent and assistant, a young man called Rasher, had proven ineffectual, a fact Mrs. Stevenson accepted with a good-tempered realism which was one of her greatest assets. One must have a genius for diplomacy to steer an enterprize through Egyptian conditions today,” she noted; and as for Rasher, “one cannot expect a Tallyrand or a Roebling combined at a guinea per diem.”

Although Mrs. Stevenson contacted the English and American Egyptologists in Egypt, seeking a suitable excavator for the Museum, her principal item of business was a proposal that the American Exploration Society, which had been founded to secure funding for Museum expeditions, should pay for the removal of colossal statues and massive inscribed architectural elements which were partially exposed at Tanis. Tanis was a remote site in the northeastern Delta and the monuments would be taken to the National Museum in Cairo. In return, she requested that the Egyptian government assign duplicate material from Tanis—i.e. statues or architectural elements which were more or less identical with the material to be deposited in the Cairo Museum—to the University Museum.

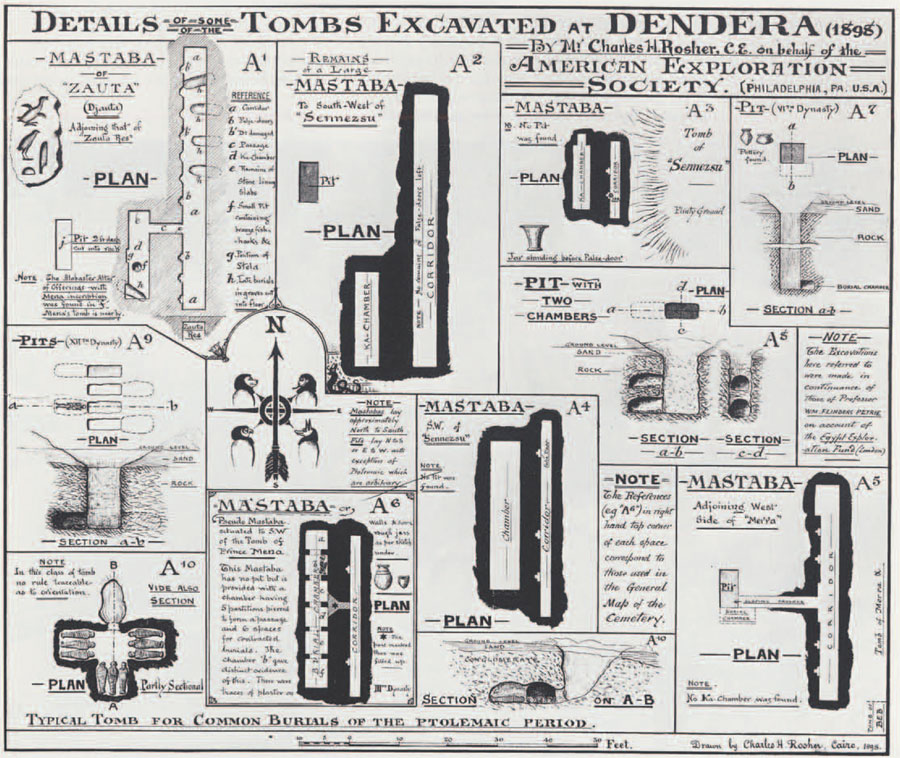

Loret, the French Director-General of the Egyptian Antiquities Organisation, quite properly turned dawn the proposal, for this was one of the rare occasions when Mrs. Stevenson’s enthusiasm led her into an error of judgment. As Loret pointed out, the appropriate way to recover antiquities was to have properly conducted excavations at Tanis followed by a division of the finds between the two museums. Sensing that Loret might be vulnerable because of rivalries within the antiquities organisation and the more generalized tension between the British and French, long-time rivals and now uneasy collaborators in Egypt, Mrs. Stevenson continued to promote her proposal with tact, skill and perseverance. She won the support of important government officials through argument and persuasion (pragmatically, she also considered bribery, but wisely rejected it). Pursuing Loret to Aswan, 580 miles south of Cairo, she made a final appeal, but he was obdurate, As her hopes for the project faded, Mrs. Stevenson’s charitable feelings towards the ineffectual Rasher cooled; somewhat waspishly she remarked; “I instructed him to go at once to Mr. Petrie—to put in two or three months’ (excavation) at Denderah under him (so that he might justify his winter’s employment).” (For Petrie and his connection with the Museum, see pp. 17 ff.)

The artifacts Rosher found were sent to Philadelphia, but in fact the first Egyptian antiquities received by the Museum had arrived (from Petrie) in 1890, the year Sara Stevenson was appointed curator of the Egyptian and Mediterranean Section. Since the Museum itself had been founded only three years earlier, in 1887, it is true to say that the history of the Egyptian Section reflects in microcosm the evolution of the Museum as a whole. For many years in the Egyptian as in some other Museum sections different individuals were respectively responsible for museology, excavation and teaching. Until the Museum’s excavations in Egypt ceased in 1932 its Egyptological field directors, while usually entitled curator, came to Philadelphia only periodically for intensive curatorial and publication work. The day-to-day management and exhibiting of the large and growing Egyptian collection was left to others, who were not professional

Egyptologists. As for teaching, formal courses in Egyptology began at the University of Pennsylvania as early as 1902 and continued—with some interruptions—thereafter, but the instructors and professors had no or only tenuous connections with the Museum. Curators and field directors did no teaching at all. It was not until 1938 when Hermann Ranke, who had been trained by the great German Egyptologist Adolf Erman, was appointed to the Oriental Studies Department that an Egyptian Section Curator became a fully affiliated member of a University teaching department.

Because of policy and structural changes over a long period of time, the story of Egyptology at this Museum is a complicated one. To simplify it we have divided it into two main topics, field-work and the collections, with research, public education and university teaching emerging as the vital links between these two topics. The current and very active and expansive phase of Museum field-work in Egypt, which began in 1967, is described elsewhere in this issue.

We must not forget however, in the need for simplification, those factors other than personal and professional activity which shaped the lives and careers of our predecessors in the Egyptian Section. These factors will emerge as critical ones from time to time in our story. The most important intellectual influences upon the professional Egyptologists associated with the Section were of course the Egyptological concepts and research methods prevalent at the time, but these changed significantly from generation to generation All Section staff members were inevitably affected by the general, always gradually changing intellectual climate, especially in so far as it was relevant to the study and exhibition of the texts and artifacts of ancient societies.

Egyptology at the Museum was strongly affected by the changing policies of that institution over 90 years and by the different personalities of the men and women who were successively the chief officers of the Museum, Also directly impinging upon the field-work were conditions in Egypt itself. From 1882 onwards Egypt was engaged in a continuous struggle—often hidden, sometimes overt and turbulent—to make itself independent of foreign rule, a struggle that did not finally end until 1952. In addition, there were both before and after this date periodic major social and economic reforms which affected the status of foreign archaeological expeditions. Egypt has been and continues to be one of the most hospitable countries in the world to the foreign scholar and excavator, but the vicissitudes of its history through this century inevitably at times seriously affected the Museum’s work. Beyond Egypt itself other events of wider significance—two world wars, the great depression, other international political and economic fluctuations, the relationships between Egypt and the United States —also affected that work for both good and ill.

Photo courtesy Egyptian expedition, Metropolitan Museum of Art.