2010 marks the centennial of the deaths of two notable individuals and the demise of a career for a third. Osman Hamdi Bey is as famous today as an artist and archaeologist as his contemporary, the photographer John Henry Haynes, is obscure. Their colleague, the Assyriologist Hermann Vollrath Hilprecht, remains at best infamous. Their three intersecting lives are the subject of the exhibition Archaeologists & Travelers in Otttoman Lands to open at the Penn Museum in September 2010.

The Photographer.

John Henry Haynes (1849–1910) might be regarded as the father of American archaeological photography, but chances are you have never heard of him. Much of his work was published anonymously or credited to others, or it simply remained unpublished. After graduation from Williams College, Haynes grew bored with life as a high school principal and jumped ship in 1880 to join the first American archaeological expedition to the eastern Mediterranean. One of the very few significant caprices of his life, this action determined the remainder of his career. When a permit to excavate on Crete was denied, Haynes found himself in Athens, where he learned photography, working as assistant to William Stillman while he prepared his second Acropolis folio. Haynes was subsequently dispatched to Assos in northwest Anatolia to be photographer to the first American School of Classical Studies at Athens excavation, 1881–83. After that time, Haynes traveled with a camera, documenting his journeys through Anatolia, Syria, and Mesopotamia. Rather than return home, Haynes taught at Robert College in Constantinople (Istanbul) and later at the American mission school in Aintab (Gaziantep). He joined the Wolfe Expedition of 1884–85, a reconnaissance mission to Mesopotamia, out of which grew the excavations at Nippur, in which Haynes was a major player. As a part of the American strategy in the region, Haynes was named the first American Consul in Baghdad in 1888.

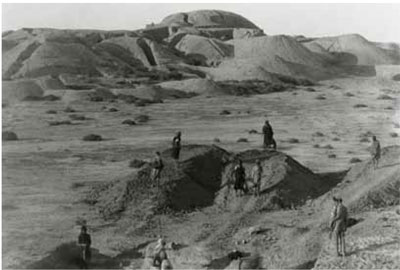

Located in the swamps of southern Iraq, Nippur was difficult of access, inhospitable in its climate, surrounded by warring tribes, and not particularly attractive. All the same, the site offered tantalizing clues to the early history of civilization, and thus the Babylon Exploration Fund (BEF) of the University of Pennsylvania was lured by the prospect of a library of cuneiform tablets. The first expedition (1888–89), led by John Punnett Peters (1852–1921), found barely enough to justify continuing; the season was marred by infighting among the participants, their difficulties exacerbated by the enmity of the locals, who robbed them and burned their camp as they departed, culminating in mass resignations. Penn’s Assyriologist Hermann Vollrath Hilprecht (1859–1925) simply refused to go back to the site. Only Peters and Haynes returned reluctantly for a second, more successful season (1889–90), when 8,000 tablets were found, but the conditions were too much for Peters. The stolid Haynes returned alone for a long third season (1893–96), during which local conditions deteriorated into what he termed “Robberdom and Murderland.” Haynes constantly feared for his life but found little sympathy from Peters in Philadelphia, who criticized his insufficient excavation reports and instructed him that “the Committee wants tablets.”

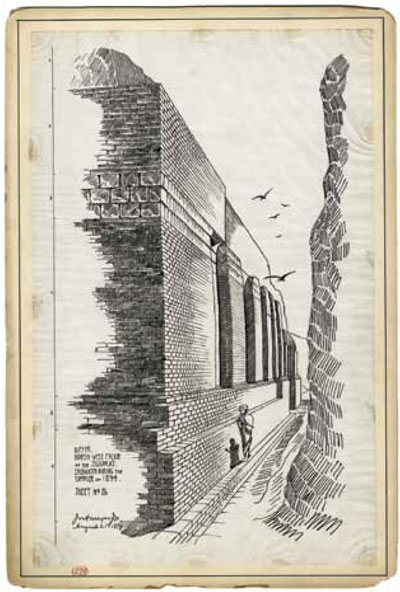

During the summer of 1894 in Baghdad, Haynes met by chance a traveling Massachusetts Institute of Technology architecture graduate, Joseph A. Meyer (1856–1894), whom he induced to join the expedition. Meyer’s insight and graphic skills made significant contributions in clarifying the architecture at Nippur. More importantly, he provided Haynes with necessary companionship in his “lonely and desolate life,” as he wrote in his unpublished account of the Nippur excavation. Less than six months later, however, Meyer was dead from dysentery, and Haynes’s mental condition deteriorated. By the time assistance finally arrived in the spring of 1896, Haynes was convinced of imminent danger and insisted on immediate evacuation—to the embarrassment of the BEF.

Haynes returned for the fourth and final season (1898–1900), but during his rest and recuperation in the United States, to the surprise of everyone, he got married. Taciturn and close to 50, he met the ebullient Cassandria Artella Smith during a visit to the Smithsonian, and they married shortly thereafter. To the consternation of the BEF, he insisted that she accompany him to Nippur. While Haynes was no great catch, his family regarded Cassandria as a floozy and a gold digger. Their relationship quickly deteriorated during the long months at Nippur, and they soon separated. Adding to the tensions, Haynes’s assistants Clarence Fisher and Valentine Geere arrived more than eight months late, due to Geere’s illness (laid low in Baghdad with “pleur-pneumonia”) and Fisher’s indecisiveness (he tended the invalid Geere, then retreated to London, then returned to accompany Geere to Nippur). To complicate matters, Fisher had developed a hopeless, unrequited infatuation with Geere, and the atmosphere at the dig house began to resemble an Edward Albee play.

In his memoirs, Geere portrays Haynes as an incompetent bungler, but in the final season Haynes hit the mother lode: what was alleged to be the Temple Library, from which 23,000 tablets were extracted. Then in March 1900, Hilprecht returned to Nippur for the first time in eleven years and took charge. By that time, most of the work was finished, and the tablets had been crated for shipment. Over the course of the next years, however, as Scientific Director of the expedition, Hilprecht discredited Haynes’s accomplishments and claimed responsibility for Haynes’s discoveries. His career in shambles, Haynes succumbed to mental illness, ending his life in an asylum.

The Assyriologist.

At the height of his fame, Hermann Vollrath Hilprecht (1859–1925) was called “the Columbus of Archaeology,” although he spent little time in the field and depended on the work of others for his “discoveries.” A talented Assyriologist, he had studied in Germany with Friedrich Delitzsch and prided himself on his “proper” (i.e. European) education. Early in his career, in 1886, he came to the U.S. to edit the Sunday School Times and was hired almost immediately at Penn, initially as a lecturer in Egyptology (the first such position in the U.S.). A few months later he was appointed Professor of Assyriology. Tapped to participate in the expedition to Nippur, he declined at first because of his “delicate health,” but overcame his misgivings when he was appointed second in command to Peters. Understanding his peculiar combination of condescension, jealousy, and hypochondria, Provost William Pepper commented, “Hilprecht will die if he does go, and he will die if he does not.”

Hilprecht went, but he complained all the way: about the Oriental paupers, the vermin, the travel conditions that were “beneath my dignity and that of the University,” but mostly about his colleagues. In letters to “my true friend” Pepper back at Penn, he railed against the willful ignorance of the team, particularly the dictatorial and “demonic” Peters (who had refused to supply him with a handgun and thereby exposed him to danger), calling the expedition a failure almost before it began. Indeed, talk of rebellion against Peters may have been the only thing to keep the expedition together.

After the disastrous finale of the first season, Hilprecht insisted that in order to save the BEF expenses, he would not return to Nippur; at the same time, he ingeniously arranged to position himself in Constantinople, at the BEF’s expense, to examine the finds before they were divided between the Turks and the Americans. He continued in this position for the next decade. Gradually, he replaced Peters as the Scientific Director but continued to oversee matters at a safe distance—from Constantinople, Jena (his second home in Germany), or Philadelphia. His instructions to Haynes, alone at Nippur, were at best vague. Meanwhile, Hilprecht ingratiated himself to Osman Hamdi Bey, the Director of the new Ottoman Imperial Museum, assisting in the organization of the Mesopotamian section and in the cataloguing of cuneiform materials. In Constantinople he was also in a prime position to oversee the divisions of the artifacts and to negotiate the necessary firmans or permits—and to impress the authorities at Penn by his achievements on their behalf without actually spending much time on campus.

Because Ottoman laws regarding antiquities did not allow for their export, foreign excavators were at the mercy of the Ottoman authorities to give them part of their finds as “gifts,” a practice Hilprecht used to his advantage. As he insisted, the antiquities from Nippur destined for Penn had been given to him “as personal gifts of the Sultan,” most of which he then magnanimously donated to the University. At the same time, he demanded the authority to limit access to and control of publication of all of Penn’s cuneiform materials.

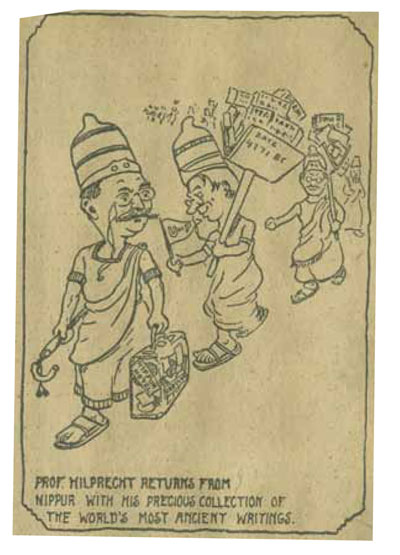

In March 1900, Hilprecht finally returned to Nippur after putting it off as long as possible. He spent a mere ten weeks at the site, attempting to put in order what had been directed from afar for the previous ten years, complaining and criticizing all the way. Claiming to have personally rescued the excavation, Hilprecht returned home to glory; newspapers wrote of his heroism leading dangerous expeditions for the past decade and of his sensational finds. Penn rewarded him with a research professorship and a three-year paid leave to catalogue the tablets and to conduct research in Constantinople.

Following the death of his first wife in 1902, Hilprecht secured his position in Philadelphia society by marrying the heiress Sallie Crozer Robinson in 1903. The pair traveled around Europe as Hilprecht lectured to great acclaim. With the publication of his Explorations in Bible Lands during the 19th Century that same year, however, public opinion of the scholar began to shift. In the book, Hilprecht overplayed his hand, touting Penn’s success at Nippur above all previous discoveries and scholarship in Mesopotamia. At the same time, he deprecated the contributions of Haynes and Peters and ignored all other members of the expedition; its success was to be credited to him alone. As his critics hastened to point out, it was Haynes and not Hilprecht who had discovered the Temple Library; moreover Hilprecht had not yet examined the tablets, most of which were still crated at the Penn Museum, so how could he know what they represented? In fact, many of the tablets used as illustrations in his book were not from Nippur at all— either they came from elsewhere or had been purchased in the bazaar. More embarrassingly, some of the artifacts from the excavation never made it to the Museum and had ended up as Hilprecht’s private property.

The most vocal critic was Peters, whom Hilprecht had replaced as Scientific Director, and with whom there was no love lost. At Peters’s insistence, Penn intitiated a formal inquiry in March 1905 that became known as “the Peters-Hilprecht Controversy.” Although conscious of his role as a power broker, Hilprecht’s relations with Assyriologist colleagues and students had frayed, and they were more than happy to testify against him. Sadly, Haynes was declared too “mentally unbalanced” to testify on his own behalf; he was represented by Cassandria, who no longer lived with him but had begun lecturing to ladies’ clubs on her travails in Mesopotamia. Ultimately the trustees of the University found the charge of “literary dishonesty” unsubstantiated. Feeling himself vindicated, Hilprecht published an edited transcript of the hearings, but his critics were not satisfied.

While obsequious to a fault, Hilprecht ultimately found himself on the wrong side of the University. When questions arose surrounding his care of the Temple Library tablets in 1910, he abruptly departed for Europe, taking the keys to the storerooms with him. The Director of the Museum changed the locks and investigated, finding the tablets deteriorating in their packing crates and unmarked as to findspot. Accused of negligence, Hilprecht resigned in protest, and to his great surprise, the trustees accepted his resignation. Even his connections within Philadelphia society could not save him. Hilprecht returned to Jena in Germany, but for all intents and purposes, his professional career ended in 1910.

The Artist, Archaeologist, and Bureaucrat.

Osman Hamdi Bey (1842–1910), Director of the Imperial Museum in Constantinople, must have puzzled at the comings and goings of the Americans, but he surely had some sympathy for them as well. Like him, they were attempting to bridge past and present, East and West. Like him, they were newcomers to archaeology, attempting to catch up with the achievements of their European colleagues. Like him, they viewed the investigation of the past as part of a civilizing mission for their country. He thus offers some parallels to the Americans’ ventures, and at the same time became a sort of deus ex machina for foreign excavators.

In fact, Hamdi Bey never intended to become an archaeologist. His father, a former Grand Vizier in the Ottoman Empire, had sent him to Paris in 1860 to study law, but he grew much more attracted to painting. He studied with the Orientalist Gustave Boulanger and was strongly influenced by Jean-Léon Gérôme (with whom he may or may not have studied), and in 1867 he exhibited three of his own paintings in the Exposition Universelle. Although he would have happily remained in France, the following year his father called him home, and subsequently he was dispatched to Baghdad as part of the retinue of Midhat Pasa, who had been appointed governor. The dramatic contrast with his Parisian life seems to have awakened his political consciousness and spurred his awareness about issues of identity, authority, and sovereignty confronting the Empire.

Nevertheless, Hamdi Bey’s years in Paris created an important component of his personal identity: he spoke French at home, dressed according to European standards, wrote his correspondence in French, and enjoyed a Westernized lifestyle, all the while acutely aware of the dramatic social contrasts of the late Ottoman Empire. His subsequent state employment situated concerns of authority and sovereignty within a more European perspective: he served as Deputy Chief of Protocol (1871); Commissioner to the Vienna World Exhibition (1873), at which he promoted the Ottoman cause with the exhibit and publication of Les costumes populaires de la Turquie; Head of the Bureau of Foreigners at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1875); Head of the Bureau of Foreign Press (1876); and Mayor of Galata and Pera (the European districts of Constantinople, 1877).

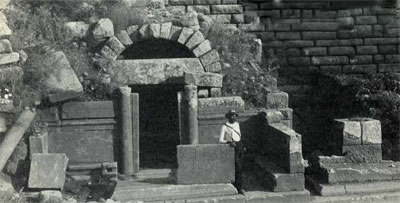

In 1881 Hamdi Bey was named Director of the Imperial Museum and in 1882 Director of the School of Fine Arts. While he had not followed his father into a vizierial post, he nevertheless found himself in a position of control over both the art and archaeology of the Empire. For the former, he established a school on the model of the École des Beaux Arts, where he served as Professor of painting. For the latter, he oversaw the construction of a new museum building and its subsequent expansion (beginning 1881, first opened 1891, expanded until 1908), and almost immediately began his own archaeological works. His 1883 expedition to the Nemrut Dag ̆ı, followed by its immediate publication, thwarted German interest in the tumulus, claiming the site for his museum and his nation. Rather than continue to allow the Empire to be the passive setting for foreign excavators and treasure-hunters, Hamdi Bey shifted the balance of power, effectively laying claim to all archaeological sites within the Ottoman Empire. He rewrote the law governing antiquities in 1883–84, prohibiting archaeological finds from leaving Ottoman territory. This change meant that his museum, rather than its European counterparts, became the repository of all new discoveries, and Hamdi Bey became the gatekeeper, to whom all foreign archaeologists had to answer.

While the antiquities law was rigid in its terms, it was more flexible in practice: “gifts” could be presented to obliging foreign archaeologists as part of Hamdi Bey’s diplomatic strategy. The American excavations at Assos had been undertaken before the law was rewritten, but the effrontery of its young director J.T. Clarke had so offended Hamdi Bey that he had not issued the export permit; Haynes had to later intervene, although he was hardly of the same stature as Hamdi Bey. Peters in turn arrived in Constantinople thinking that anything in the Imperial Museum was for sale; he was rebuffed. Then, not realizing Hamdi Bey was the author of the new antiquities legislation, Peters criticized it to his face. He did not make a favorable impression. Hilprecht fared much better, for not only was he a master of obsequiousness, he was also a European gentleman who could appeal to Hamdi Bey’s European identity. Moreover, he arrived with an important bargaining chip—a rare understanding of Assyriology and cuneiform scripts that could be put to full advantage in setting up the new museum.

As the Americans expanded their activities into the Middle East, so did Hamdi Bey, with the major excavation in 1887 at the Royal Cemetery at Sidon, from which numerous grand marble sarcophagi were unearthed, including the famed Alexander Sarcophagus. The glory of his new museum was found in his own excavation.

As founder of the art academy, originally adjacent to the museum, Hamdi Bey continued to paint in the French manner and to train students. While he did not exhibit his paintings within Turkey, they began to gain attention abroad, and were exhibited and sold in Europe and America. Foreigners interested in acquiring permits to excavate or to export antiquities quickly realized that appealing to Hamdi Bey as a European artist and intellectual was an effective strategy. Thus, for example, in 1892 two of his paintings were exhibited at the Palais d’Industrie in Paris; one was purchased by the French, through the ministrations of Léon Heurzey, Curator of Oriental Antiquities at the Louvre, who was subsequently congratulated, because “nothing could be more pleasing to an artist who can render us services and who is important to satisfy.” In the following year, Hamdi Bey was elected corresponding member of the Institut de France; the French in turn received a coveted antique. The purchased painting was not exhibited and ended up in the Musée des Colonies. In fact, the two paintings had been intended for the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago and ultimately Philadelphia, where Penn was following a strategy similar to the French. When At the Mosque Door, an Orientalist genre painting typical of Hamdi Bey’s oeuvre, finally arrived in Philadelphia alone, Peters penned a note to Hamdi Bey enquiring the whereabouts of the other painting. Nevertheless, the Penn Museum purchased the one for 6,000 francs (much more than the French had paid for its companion), while offering Hamdi Bey an honorary doctorate (1894) and honorary membership in the University Archaeological Association (1895).

Viewed from the outside, the diplomacy might seem heavy handed and the motives fairly obvious, and yet Osman Hamdi Bey succeeded in balancing his position between two worlds to satisfy both personal and national agendas. He could coexist as a European gentleman of culture and as an Ottoman diplomat. He recognized that the continuing contacts with the West were a necessary component to modernism, just as his position within the Ottoman bureaucracy was necessary to its success.

A Final Intersection.

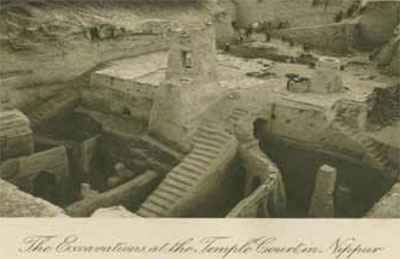

When Hilprecht’s book Explorations in Bible Lands appeared in 1903, he selected one of Haynes’s photos of the Nippur excavations as the frontispiece. Hilprecht immediately presented a copy of the book to Osman Hamdi Bey, who in turn employed the frontispiece image as the subject of a monumental painting, The Excavations at Nippur, which he signed and dated in the same year. Unique among the artist’s oeuvre in both its subject matter and style, the painting seems to have been commissioned by Hilprecht on behalf of Penn, probably intended as the backdrop for the Museum’s display of tablets and artifacts from Nippur. The impressionistic sfumato style distinguishes the painting from the crisp realism of Hamdi Bey’s earlier Orientalist paintings. While the artist commonly used photographs to compose his paintings, in this instance the style seems to depend on the frontispiece image, which had been printed in grainy sepia tones. As an amusing gesture of friendship, Hamdi Bey inserted Hilprecht into the painting, depicting him examining the pottery in the middle distance. In actual fact, the frontispiece photograph was taken early in the third campaign (1893–96), when Hilprecht was nowhere near Nippur.

Before the painting could be shipped to Philadelphia, controversies erupted over Hilprecht’s “literary dishonesty” in the book whose frontispiece served as the basis for the painting. Indeed, just as Hamdi Bey had literally painted Hilprecht in a favorable light, in the book Hilprecht had figuratively painted everyone else as unfavorably as possible. A power struggle at the Museum put Hilprecht out of favor, and with the brewing scandal, the grandiose Nippur gallery he envisioned could only serve as another source of embarrassment. When the University balked at displaying the painting, Sallie Crozer Robinson Hilprecht purchased it as a gift for her husband. It finally came to the Penn Museum in 1948, as a bequest of Mrs. Hilprecht’s granddaughter, Elise Robinson Paumgarten. Never before displayed publicly, the painting will now be the centerpiece of the Penn Museum exhibition Archaeologists & Travelers in Ottoman Lands.

Eldem, Ehdem. “An Ottoman Archaeologist Caught between Two Worlds: Osman Hamdi Bey (1842–1910).” In Archaeology, Anthropology and Heritage in the Balkans and Anatolia: The Life and Times of F.W. Hasluck, 1878-1920, 3 vols., edited by David Shankland, pp. I: 121-49. Istanbul: Isis Press, 2004.

Frith, Susan. “The Rise and Fall of Hermann Hilprecht,” The Pennsylvania Gazette (Jan.-Feb. 2003). Accessed online (27 May 2010): http://www.upenn.edu/gazette/0103/frithsidebar.html

Geere, H. Valentine. By Nile and Euphrates: A Record of Discovery and Adventure. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1904.

Haynes, John Henry. unpublished notebooks, 1884–1900, Penn Museum Archives.

Hilprecht, Hermann V. Explorations in Bible Lands during the 19th Century. Philadelphia: A. J. Holman, 1903.

Kuklick, Bruce. Puritans in Babylon: The Ancient Near East and American Intellectual Life, 1800–1930. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996.

Peters, John P. Nippur or Explorations and Adventures on the Euphrates, 2 vols. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1897, 1904.