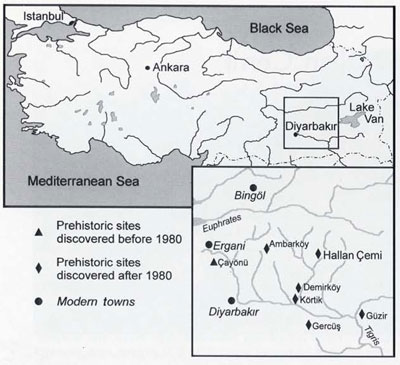

Until recently, Southeastern Anatolia (Turkish Asia Minor) was largely written off as a cultural backwater during the Neolithic period, the long transition from a hunting and gathering lifestyle to settled farming. That perception changed dramatically with the discovery of Hallan Çemi. The small Protoneolithic-period site was discovered in 1989 during an archaeological reconnaissance prior to construction of a dam on the Batman River. Excavations, which began in 1991 under the direction of Michael Rosenberg, have revealed it to be the oldest known permanently settled village in Anatolia, dating to more than 11,000 years ago.

The village sat at the edge of a riparian forest made up of ash, willow, poplar, and buckthorn. The surrounding foothills were covered with an oak, pistachio, and almond forest. Fauna consisted of wild sheep and goat, wild cattle, red deer, wild cat, brown bear, wild pig, and beaver. Turtles and clams were found in the Sason River.

The village was made up of semisubterranean huts of wattle and daub set upon stone foundations. Each hut was linked to an exterior plastered surface where many domestic activities would have been carried out. The huts rarely exceeded 2 meters in diameter and were probably used primarily for sleeping. Two large structures, found in the upper levels of the site, were 6 meters in diameter and had stone benches and plastered hearths. One contained a wild cattle skull that had originally hung on the wall. The size and nature of these structures and associated deposits of exotic materials suggest that they may have had some ritual or community-wide function.

Flint and obsidian were used to produce stone blades and chipped stone tools. The flint was found locally; the obsidian came from Lake Van and Bingöl. The presence of relatively large amounts of obsidian suggests that trade networks existed. This is further indicated by the presence of malachite, a copper ore often used as a pigment, probably from the region around Ergani.

An unexpected feature was the presence of elaborately carved and decorated stone howls and sculpted pestles. Vipers, a common motif, adorn some of the bowls. Decorative motifs would become important later, suggesting that the florescence of the later Anatolian Neolithic at sites such as Catal Höyük had its roots in early villages such as Hallan Çemi.

A major aim of the excavation was to gain information concerning the subsistence economy. Animal hone and plant remains recovered from Hallan Çemi show that the inhabitants made their living almost completely from wild resources. This is a pattern that has been well attested throughout southwest Asia and of itself is not surprising. The big surprise was the absence of any wild cereals. Instead, bitter vetch, wild lentils, seeds from Gundelia (a spiny plant), almonds, and pistachios were the staples. Many archaeologists have thought that the exploitation of dense stands of wild ‘cereals was a necessary precondition for permanent preagricultural settlements. But the evidence from Hallan Çemi suggests that any dense resource is sufficient and calls into question the hypothesized causal role of intensive cereal exploitation in precipitating the emergence of permanent settlements. Wild sheep, wild goat, red deer, and wild pig provided much of the meat consumed at Hallan Çemi. The importance of sheep and goat in southwest Asia.

Today has led to the presumption that they were the earliest animals domesticated. In this, Hallan Çemi held another surprise. The earliest attempts at domesticating animals, apart from dogs, involved pigs. Apparently pigs were ideal in part because they are extremely efficient at converting plant foods into protein, they have a high fertility rate, and the young imprint easily on humans, making them easy to tame. Pigs were also easy to obtain since they inhabited the nearby riparian forest and may have been attracted to garbage in the village.

The presence of special-purpose buildings, sophisticated craft production, objects used for record keeping, trade networks, and experimentation in animal domestication during the Protoneolithic period shows a high level of complexity. But these are not isolated phenomena. Since the discovery of Hallan Çemi, other contemporary sites have been found that will refine our understanding of this crucial period. Today, Hallan Çemi lies under a lake, and many other sites will suffer the same fate in the near future. But they indicate that the reason southeastern Anatolia showed no evidence for habitation during the Neolithic was because no one had bothered to look for it. It is, perhaps, a paradox that dam construction, the very thing that promises to destroy archaeological sites, has proven invaluable in opening our eyes to the richness of Neolithic society.

— Brian L. Peasnall,

Robert H. Dyson, Jr., Postdoctoral Fellow

Acknowledgments: This report would not have been possible without the analysis and interpretation of the animal and plant remains by Richard Redding and Mark Nesbitt. Funding and other support for the Hallan Çemi excavations was provided by the National Science Foundation, National Geographic Society, University of Delaware, University of Delaware Research Foundation, International Nut Council, and Mobil Exploration Mediterranean Inc.