Because of ecological and environmental concerns, much attention has been given in the past few years to the erosion of natural habitats and the desiccation of wildlife in the face of spreading urban and technological development. But the same thing has been happening to people as well. Everywhere around the globe whole tribes and populations are being abused and forced from their lands and are having their folkways threatened. The threat proceeds on almost a daily basis, and is reaching the crisis stage.

Because of ecological and environmental concerns, much attention has been given in the past few years to the erosion of natural habitats and the desiccation of wildlife in the face of spreading urban and technological development. But the same thing has been happening to people as well. Everywhere around the globe whole tribes and populations are being abused and forced from their lands and are having their folkways threatened. The threat proceeds on almost a daily basis, and is reaching the crisis stage.

In Panama, engineers are laying plans for building the final link of the Pan-American Highway through the dense jungles of the “Darien Gap” which separates Panama from Colombia. There, the Cuna and the Choco (Embera) Indian tribes are facing the prospect of what will happen to them if the highway is completed. If the road pushes through, it will mean the loss of much jungle and many of their game animals and a much more intensive contact with unscrupulous traders. A proposed new dam will be an even greater threat, since it will flood 80 percent of their land and involve the resettlement of about the same proportion of their population Significantly, the water will also push them back beyond the limits of the land granted to them by the Panamanian government so that they will no longer have any title to their land.

When the primitive Stone Age Tasaday tribe emerged from their rain forest on the Philippine island of Mindanao in 1971, they were startled by helicopters and endangered by feuding and competitive logging companies.

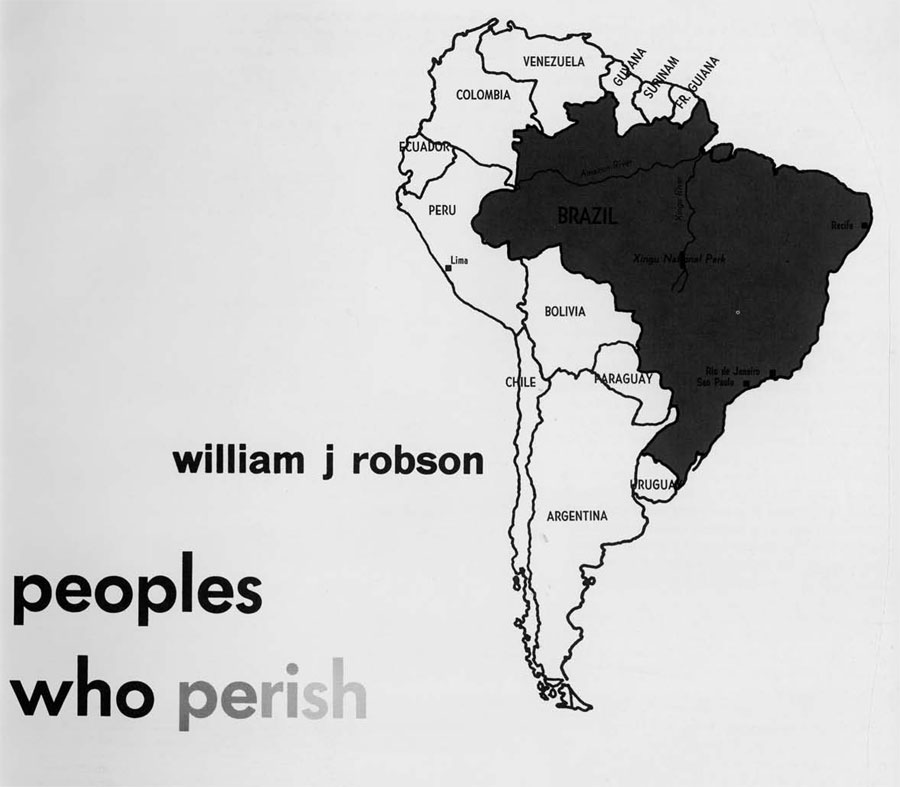

In Brazil, Indians are being harassed by squatters, prospectors and settlers who are attempting to open up new territories. There, government policy has been traditionally enlightened on behalf of the Indian, but in 1971 the government permitted the construction of a highway through Xingu National Park, the Indian sanctuary built up over the past twenty years by Claudio and Orlando Villas Boas, who were featured in Adrian Cowell’s award-winning documentary The Tribe That Hides From Man. Xingu has been given other land in compensation, but this land has already been settled, and some of the forest burned, by squatters and prospectors and it contains no Indians.

Brazil, a vast country which is only now being seriously developed under twentieth century technology, offers a dramatic example of the encounter between modern and primitive societies. In February, 1969, writer Norman Lewis observed in London’s Sunday Times Magazine that many Indian tribes in Brazil had been almost annihilated since the turn of the century and that the means of annihilation had been poison, dynamite, machine guns and torture. Disease had been the chief factor and it was introduced both purposefully and as a natural consequence of contact with disease-bearing whites. Lewis concluded that unless such processes were halted, within a decade there would be no survivors.

And, in the late 1960’s, Brazil’s Indian Protection Service was disbanded because it was found to be riddled with corruption. Many of its functionaries were prosecuted for crimes ranging from theft to murder. A certain reform came with the establishment of the National Indian Foundation (Fundacao Nacional do Indio, or FUNAI). Yet while the old Service had been directly responsible to Brazil’s president, FUNAI was made a department of the Ministry of the Interior. Since one of the most important concerns of the Ministry is the development of the interior of the country by the construction of roads and highways which bring settlers and industry into the jungle, the Indian is often displaced and suffers as a consequence.

Perhaps the saddest fact of all is that the many tribes in Brazil and elsewhere seldom meet the best representatives of modern culture. Instead, their first contact is often with greedy mineral prospectors and the rabble employed by great landowners, banks and investment companies and other agencies which seek to empty the land and sell it for a profit. Even missionaries, usually a group noted for a higher ethical and educational standard than the others, have sometimes brought tragedy along with benefits. The introduction of clothing often means the introduction of a virus, and the policies of certain groups with regard to diet have often proved detrimental to native tribes.

Primitive peoples thus face a multitude of threats to their integrity and soon many of them may vanish. Their loss to the greater body of mankind would be a real one: in human terms alone they are often among the earth’s most pleasant and gentle peoples. The Tasaday, for example, have no words in their spoken language for weapons, hostility, or war.

As knowledgeable observers of the environment, primitive peoples are a repository of wisdom. The Indians of the Western Hemisphere have already introduced the civilized world to cocaine, quinine, rubber, potatoes and maize. Tribes in the Amazon basin (which has more plant species than any other locale in the world) are familiar with many herbal remedies and plant properties. Modern scientists build upon their knowledge and from curare, used by the Indians for paralyzing game, they have produced d-tubocurarine, which has played a vital role in heart transplant operations. The Indians also have a great knowledge of the manufacture and use of hallucinogenic drugs, which is of particular importance to modern cultures.

Other primitive peoples elsewhere have lent inspiration to the art forms of the twentieth century and the varied sociological profiles of these groups have given contemporary man an insight into his own life-ways.

What can be done about this human erosion and loss? Can the world’s primitive peoples be defended against the co-option of personal or corporate greed, governmental indifference and misdirected technology and population pressures?

Some people, particularly in Great Britain, began to seek in earnest for answers after Norman Lewis’ article appeared in The Sunday Times Magazine. Nicholas Guppy, the author of a well-known book entitled Wai Wai (about a Guyana tribe of the same name) and anthropologist Francis Huxley, son of Sir Julian Huxley, who had written about South American Indians in Affable Savages, decided to do something about the situation. They offered to organize a trust to raise money for, and to survey the problems of, primitive peoples everywhere.

Designated originally as the Primitive Peoples Fund, the trust is now known as Survival International and has helped to set up similar organizations in the U.S.A. and Venezuela, and has links with groups in France, Holland, Canada and Scandinavia which are also involved in work with primitive peoples. In America, its counterpart is known as Cultural Survival.

The Chairman of Survival International is Robin Hanbury-Tenison, a 37-year-old Briton who coordinates his activities while working a 600-acre farm in Cornwall. A member of the Council of the Royal Geographic Society, he has informed English-speaking peoples about the plight of primitive tribes through newspaper and magazine articles and radio and television appearances. For fifteen years as an explorer he has taken part in nearly a dozen large and small expeditions throughout the world. In 1958 he and a partner, Richard Mason (who was later killed by a hunting party of Kreen Akrore Indians), made the first land crossing, by jeep, of South America at its widest point, east to west from Recife, Brazil to Lima, Peru. He also made a lone journey by river from the Orinoco to the Plate, which, along with the transcontinental crossing, was the subject of his first book, The Rough and the Smooth. All of these adventures brought him into contact with indigenous peoples and gave him the desire to be of help to them.

With one full-time employee (a secretary) and numerous volunteers, Survival takes a two-fold approach. First, it seeks to gather information about what is happening to primitive peoples around the globe. Secondly, with this information in hand, it brings pressure to bear at the government level so that these peoples stand a better chance of withstanding future threats to their integrity.

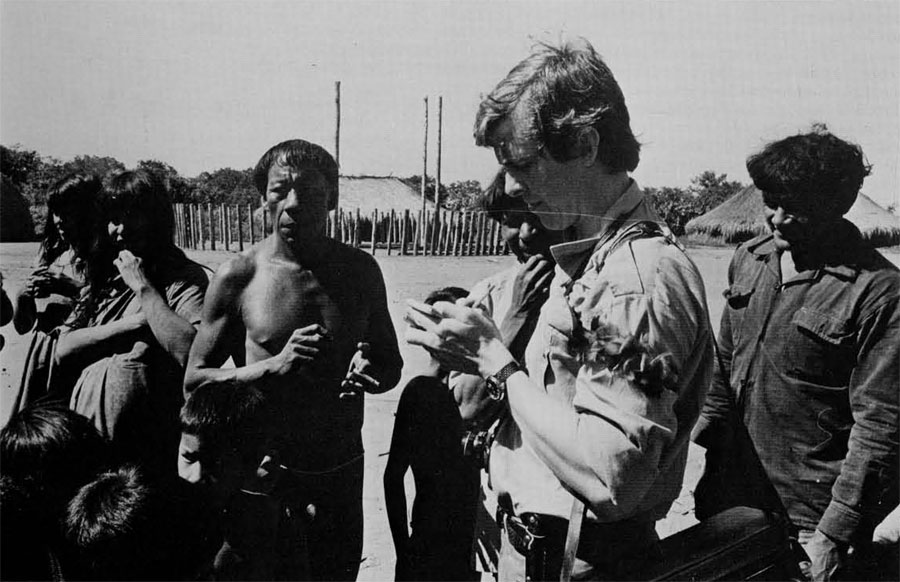

Firsthand knowledge is important. In January, 1971, Hanbury-Tenison went to Brazil upon the invitation of its government to check the areas that Norman Lewis had written about. Six months earlier, a Red Crass team had made a medical survey of the Indian settlements and had made a disturbing report. But the Brazilian government assured Survival that all of the Red Cross’s recommendations had been implemented.

However, when he arrived in the settlements, Hanbury-Tenison discovered that most of the recommendations had actually been ignored. Disease was rampant—in one area half of the people, including nearly every woman and child, had been wiped out by disease—and the population appeared to be declining rapidly.

As a consequence, there was another follow-up. In August, 1972, the Aborigines Protection Society, which is incorporated in the Anti-Slavery Society for the Protection of Human Rights, sent a Mission from England to Brazil at the invitation of the latter government. Led by Dr. Edwin Brooks, Senior Lecturer in Geography at the University of Liverpool, who had investigated the circumstances of Guyana’s Indians in 1969 on behalf of Amnesty International, the United Nations Association and APS, the Mission sought to assess the conditions of Brazil’s primitive population and to offer suggestions for improvement. Members of the Mission included author-publisher John Hemming and Francis Huxley, both of whom had assisted in Survival’s founding, and ethnologist Rene Fuerst. All had previously studied Brazilian tribes at first hand.

After two months of exploration, the Mission was able to gain a picture of the Indian’s most pressing problems. It concluded that the safeguarding of his land rights—often inadequately protected and enforced—deserved the highest priority. It also found that some of Hanbury-Tenison’s recommendations appeared to have been implemented, which seemed to suggest that Survival’s own missions were of value. The APS discovered that FUNAI recruits were receiving a brief training course for the first time, recruitment was good, and the incoming personnel were enthusiastic, although this situation might not remain if top posts “continue to be monopolized by elderly outsiders, generally military men.” The investigators found that there were improvements in the educational calibre, pay and living conditions of the staff on Indian posts. They found that many religious missionaries, both Catholic and Protestant, were re-thinking their attitudes toward tribal religions and improving the anthropological side of their work. The medical and educational assistance provided by the missionaries, they saw, was markedly superior to that given by FUNAI, although rivalries between missions were still dividing many tribes. Ultimately, an improved and properly administered FUNAI ought to shoulder full responsibility for all of the Indians of Brazil, the APS team believes.

Dr. Brooks and his associates think that some of the budget for each great new road in Brazil should be specifically allocated to the continuous medical and social protection of those threatened by it, and they observed that the Indians need and should be provided with parks and reserves that truly reflect their territories and are really inviolate. The survey team concluded, however, that modern technology and an insatiable economic system, with its bases in world capitals, are probably more responsible for the Indians’ problems than the alleged failings of the Brazilian government to care for them, or the desire of the poor citizens to find a new life in the interior.

Survival’s own surveys, and follow-ups by organizations of professionals like the APS team, are ideal ways in which to heighten a nation’s awareness of the needs of its primitive minorities and its strengths and weaknesses in dealing with them, Hanbury-Tenison believes.

“We’re not trying to leap in with both feet,” asserts the organization’s hardworking chairman. “We’re not a charity in the sense that we go out and collect blankets and food for starving babies. Primarily we’re a study group. Our main concern is to focus the public’s eye on the problem.”

Still, Survival has managed to send monies and medical supplies to primitive tribes. It is a registered charity and as such welcomes contributions. Depending on the amount, they are used in two ways.

“The first is for normal administrative expenses and these could be expanded greatly as we run on a very tight budget at present,” Hanbury-Tenison explains. “The second use involves larger sums for specific purposes which we can arrange to transmit to areas of need. However, rather than attempt to raise these large sums, we currently try to persuade the bigger established charities to support projects recommended by us.”

Aside from caring for their acute needs, what actually can be done—or should be done—for threatened primitive peoples remains very much an open question at this point as far as Hanbury-Tenison is concerned.

“What is the answer for these people?” he asks. “Is it right to force primitive people into our society? Does the answer consist of setting aside closed areas for tribal peoples? Is the answer the immediate education of all the children—even though we’ve seen this has not worked with the North American Indian? Can there, in fact, be any practical future for people. who, in thousands of years, have shown no desire to integrate with the rest of the world?”

He believes that “maybe the answer is to slow up a little. Don’t take their land from them until we’ve found an answer.”

In general, the team foresees that the more primitive or recently contacted groups will need protection for a long time to come.

For more acculturated groups it sees a need for better education and practical training and a more positive policy to remove such Indians from the status of legal minors and to give them some real authority. “The alternative strategy of treating Indians as eternal children can only prolong their alleged immaturity” the team states in the summary of its report. But it believes that the Indians themselves must set the rate for change, which should come only at a speed they can accept, and that each Indian nation should be treated as a separate case, with its distinct culture, history and problems.

The complete report by the APS team, entitled Tribes of the Amazon Basin in Brazil 1972, was published by Charles Knight & Co., Ltd., London and Tonbridge in 1973.

Hanbury-Tenison thinks that it may be possible to provide a breathing space, a means for primitive and civilized peoples to get to know each other, as is the case to a limited extent at Xingu National Park in Brazil.

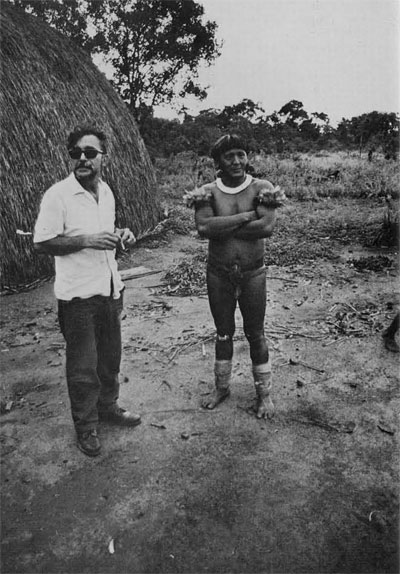

The park, located in the country’s interior, is the home for approximately 1,500 Indians from fifteen tribes. There they are given the chance to adapt to the modern world at their own pace while preserving their pride, culture and skills. They are protected from settlers and prospectors and even missionaries are not allowed into the park. Six FUNAI employees administer the 8,900square-mile reserve and there is an Indian at each post within the park who is responsible for day-to-day operations.

The Indians live in villages of palm-thatched communal huts and hunt and fish in nearby lagoons and rivers. They are relatively self-sufficient and live much as they would in the jungle beyond the park’s boundaries, except for medical service managed by the Sao Paulo School of Medicine which supplies most of the medicines and sends volunteer doctors and nurses to the reserve during their holidays and as part of their training. Emergencies are handled by means of the airstrips which are situated by all villages located at any distance from a given post.

“The Indian is happy, he is complete, he needs none of our culture for his happiness—only our medicines to protect him from our ills,”Claudio Villas Boas, one of the park’s founding brothers and a FUNAI employee, told Hanbury-Tenison at Xingu.

Villas Boas believes that the Indian should be left alone and only given the help he needs and wants. “The Indians already have a perfectly developed social system. They do not need change. Rather it is we who need to change our attitudes toward them. The problem of primitive peoples in the world is a worldwide one and should not in any way relate to an individual government’s own development programs.”

He sees no benefit in a hurried attempt to integrate the Indian into Brazilian society. Adoption of the life of the prospector or farmer would mean disruption and a less satisfying existence than he has now, and entrance into the favelas, or slums, of Rio and Sao Paulo would place him lower still, He believes, as does Hanbury-Tenison, that the most vital priority is to protect the Indian’s land rights, guaranteed in the Brazilian Constitution but so often ignored.

Survival has managed to send some relatively small sums to the Villas Boas brothers for medical work, and it was instrumental in providing £5,000 for an airplane for use in their tasks and assignments on behalf of the Indians. It has also arranged for the nomination of Claudio and Orlando for the Nobel Peace Prize for the past several years, affirming the backing of such distinguished and varied authorities as Sir Julian Huxley, Professor Claude Levi-Strauss, Dr. Edmund Leach and Peter Scott, as well as the American Anthropological Association and the Societes d’Americanistes of France and Switzerland. The brothers, who have already won several awards and honors for their work, are preparing to retire. One of their most recent concerns has been the contact of the Kreen Akrore Indians, an attempt which was noted in The Tribe That Hides From Man and which is now being conducted by the young Indian expert Apoena Meirelles, whose own father, Francisco, has pacified several tribes. The younger Meirelles was, in fact, named after an Xavante chief whom his father once encountered.

The creation of reserves like Xingu National Park is one means of aiding the world’s primitive peoples and protecting them from exploitation, but there are others. One is to try to employ lawyers to define the existing rights of indigenous populations in the land they inhabit and to get new rights accepted. It might be possible that the right of occupancy, which many primitive peoples including the Brazilian Indians possess, could be translated into actual title deeds, even though these might have to be held in common by the tribes and not by individuals.

Several states in the Australian Commonwealth have moved to secure the land rights of their Aboriginal populations, and the new Labour Party government of Prime Minister E. G. Whitlam is seeking to determine land rights in the Northern Territory where mining is being conducted on Aboriginal reserves, and to bring Australia’s native population into the country’s mainstream.

In the Philippines, President Marcos has established a 55,000-acre sanctuary in the vicinity of the Tasaday tribe, putting an end to the threat by logging companies. Manuel (Manda) Elizalde Jr., who was instrumental in introducing the Tasadays to the modern world, is doing much to help the primitive peoples of his country from being injured by the twentieth century. A Harvard-educated industrialist and President Marcos’ cabinet secretary for national minorities, he also serves as president of Panamin, a government-supported foundation devoted to such people in the Philippines, and seeks to obtain legal counsel for tribes which are being threatened by land-hungry settlers and politicians.

One source of help for primitive peoples may he the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP), which was conceived at the U.N. Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm in 1972, It is the only program so far established by the international community, through the governments which are members of the United Nations, to deal with environmental issues.

And, while concern over pollution and care for the world’s environment is central to the Program, one of its particular policy objectives is “to help governments identify and preserve natural and cultural areas which are significant ton their countries and which form part of the natural and cultural heritage of all mankind.” And Maurice F. Strong, the Canadian who is UNEP’s first executive director, is overseeing plans for a U.N. Conference-Exposition of Human Settlements, which will take place in Vancouver, B.C. in late Spring 1976. There, the problems and promises of population growth, technological change, poverty, pollution and resource constraints—germane to primitive as well as advanced peoples—will be carefully examined.

In the United States, the concern for the needs of primitive peoples is being implemented through Cultural Survival, Inc., which was started by Dr. David Maybury-Lewis of the Department of Anthropology, Peabody Museum, at Harvard University. It’s a tax-exempt, incorporated charitable organization which aims to provide information concerning, and aid to, small-scale societies faced with physical and/or cultural obliteration. Through its Cambridge headquarters it will maintain close contact with organizations and individuals throughout the world who are similarly concerned, and it hopes to work to support international bodies whose aims coincide with its own.

At this time, Cultural Survival is functioning in a directorial capacity for the Harvard-initiated Bushman Project in East Africa.

“Cultural Survival heartily welcomes volunteers,” Dr. Maybury-Lewis says. “In fact, it’s been staffed nearly exclusively by Harvard student volunteers. We haven’t yet had extensive public response. However, any response we have received has been quite favorable.”

Persons who would like to lend their support to Cultural Survival, Inc., may contact the organization at 11 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, Mass. 02138, Headquarters for Survival International is Benjamin Franklin House, 36 Craven Street, London WC2N 5NG, England.

Robin Hanbury-Tenison intends to keep the spotlight on the needs of primitive peoples as much as he can, despite a heavy schedule of other demands and duties. His book on his Brazil survey, A Question of Survival, first published in Great Britain by Angus & Robertson, has recently been issued in the U.S, by Charles Scribner’s Sons, His wife Marika, who writes a Sunday newspaper cooking column in addition to caring for her two children, authored her own light and entertaining account of the Brazil visit. Published as For Better, For Worse, by Hutchinson in England, it has been released in America as Tagging Along by Coward, McCann & Geogehegan.

Now that their needs and problems are being given more publicity Hanbury-Tenison is hopeful that the world’s primitive peoples will stand a better chance for equity from this day forward. “I find on the whole that the overall problem throughout the world is an acute one and the fact that people are so concerned about it is a matter of great hope,” he says.

But he is equally impressed with the vision of Claudio Villas Boas. While busily engaged in the details of Xingu’s administration, the Brazilian Samaritan takes a philosophical view of the future which embraces all of the world’s peoples, primitive or modern.

“Claudio sees a third world coming, after Capitalism and Communism have both failed,” Hanbury-Tenison says. “It will arrive out of an awareness that we have over-exploited our world and that further exploitation will only bring about our own destruction. A new respect for cultural diversity will create a world in which the ways of an individual or a group will be respected and it will not be necessary to conform to certain rigid principles. It will be a world in which the Indian will have a place in society.”

Villas Boas regards Hanbury-Tenison and Survival’s existence as the first sign of the new world’s appearance.

Suggested Reading

1973

The Horizon Book of Vanishing Primitive Man

American heritage Publishing Co.