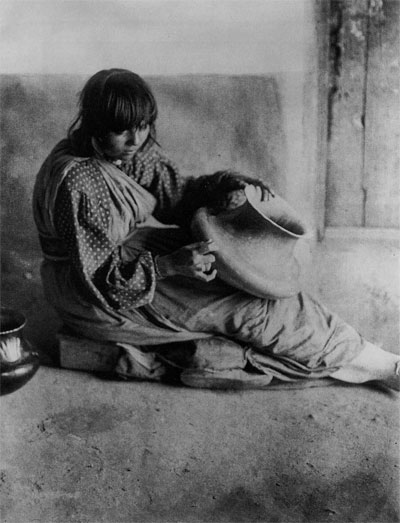

Courtesy Museum of New Mexico, neg. no. 4145. Photo by T. Harmon Parkhurst.

About 10 miles from my home in Santa Clara Pueblo, is Puce, the home of my ancestors. Puce sits on a mesa top and overlooks the Rio Grande valley. It overlooks our homes. In Puje, among the ruins of my ancestors’ homes, are the remnants of the things they used in their everyday lives. We visit and revisit our ancestral homes to connect with the past and with the spirits of those who have passed on. Prayerfully, silently we thank those spirits that, in their quiet way, welcome us to their place. If the day is good, if an extra nice pottery piece is found, it tells us that we have been “living right,” that we are remembered, and are one with our ancestors.

Clay, Community, and Cosmos

My great-grandmother, Gia-Kuhn, Mother Corn, born in the 1870s in Santa Clara (see map on p. 3), raised Cia, my mother, and taught her pottery making at an early age. My mother had eight children and all of us were introduced to pottery making as children, just as she was. Together we went for clay, helped mix the temper with the clay, and gathered materials for firing. As we grew to adulthood, we made our own pots.

Museum Object Number: 91-26-48.

For me, the making of pots was not a simple matter. I struggled with the idea of placing a monetary value on the pots. Therefore, I gave many away to those with whom I felt a spiritual kinship. It was a way of expressing and sharing friendship. Yet, I faced the reality of seeing pottery in the marketplace, and I recognized that economics had become a principal motivating force in pottery making because it provided a major source of income for my community. My inner struggle was a microcosm of the conflicts that have come about in the community because of the complexity of economic, social, and political changes.

Pottery is an old tradition that continues with strength in many Pueblo Indian communities. In Santa Clara Pueblo the making of pots embodies a cultural continuity that not only links us to our ancestors but calls forth the presence of our old Tewa cosmology. Nung-ochuquijo, meaning Unripe-earth-old-lady, is a term used by those who know to express the belief that earth, the nurturing being, coins the human being and together they give the pot form and life. The alive, organic nature of the clay is obvious. Clay and people interact on a daily and continuous basis. People talk with clay throughout the entire process of pottery making. Prayers are said when the clay is to be taken from the ground. The clay is always touched with respect and continuously asked to understand the human condition. It is understood that the human has an interdependent relationship with the clay. The clay is dependent on the human For its expression as a container and the human is dependent on the clay for the essential notion of containment in ceremonial and daily life.

University Museum Negative no. 45502. From E.S. Curtis, The North American Indian, vol. 17, no 602; photogravure from photograph copyrighted 1905.

The notion of container is crucial to the world view of the Pueblo. The lower half of our cosmos is a pot which contains life. It is the womb of the mother. The Siva, or the community house of the Pueblo, is akin to a pot when it is seen as a container of community activities. The notion of containment also is seen in the plaza which contains the outdoor community activities and is bounded by the house forms and the hills and the mountains. As the house forms are made of the mud of the earth, so are the pots which in their ceremonial role even contain lakes, or blessed water. Pottery shares this most crucial Pueblo notion of the container, along with the house and community form.

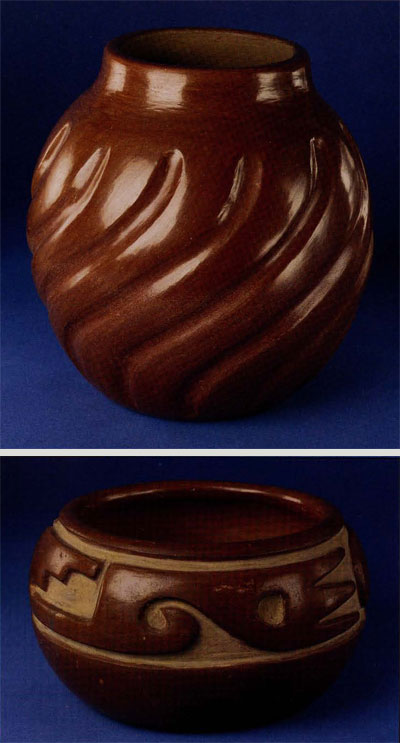

Even the elements of Pueblo pottery design always refer to the cosmic view of the world. They continually restate the connectedness of all natural elements, including humans. Mountains, clouds, lightning, water, raindrops, seeds, corn, flowers, water-serpents, bears, and feathers are incorporated into spirals and lines of continuous movement which represent the connective breath of the universe (Figs. 2, 5a,b). All represent the complex system of interrelatedness within which humans dwell. The role of pottery in our life is to bring the human into oneness with the earth through clay. Pottery production is a symbolic expression of the creative potential of the human spirit in collaborative and cooperative interaction with the earth.

A Changing World

Courtesy Museum of New Mexico, neg. no. 42274. Photo by Dorothy Stewart

Through the process of making pottery we can see our beliefs and images reflected and we can also see the intrusive influences of Western values. Our community lives in two worlds, Western and Pueblo. The encounter with the Western world has brought about changes that have ruptured the process that links us to our Pueblo world. One of the major influences has been the impact of tourism, beginning with the coming of the railroad.

The Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad reached Santa Fe on February 9, 1880. Some months later the Denver and Rio Crande Western Railroad pushed into Espanola on its route along the Chama River. The impact that these two railroads were to have on Pueblo pottery, and in the case of the Denver and Rio Grande, on Tewa pottery, cannot be underestimated. Tourists came by the carload to experience the Santa Fe Railroad’s image of the American Indian and to glimpse the simpler, mystical world of the Pueblos. This image was so strong that tourists desired nothing more than to carry a piece of that life back to their urban, secular worlds. The economics of the tourist trade created tourist pottery.

Jar- Museum Object Number: 59-14-15

Bowl- Museum Object Number: 59-14-13

The tourist trade in pottery at Santa Clara was part of the shift from a barter or trade economy to a cash economy. As a result, Santa Clara Pueblo women became wage-earners, as they were the primary makers and sellers of pottery (Figs. 3, 4). Parallel to the tourist trade, and in many ways reinforcing it, was the interest shown by ethnologists and archaeologists in the past and present Pueblo culture. Pueblo pottery was being made to fit the sensibilities of the Anglo-American tourist and anthropologist.

During the 1920s, several organizations emerged in the Santa Fe area that had an impact on Pueblo pottery making. These were the New Mexico Association on Indian Affairs (now the Southwest Association on Indian Affairs), the Pueblo Pottery Fund (now the Indian Arts Fund), and the School of American Archeology (now the School of American Research). The efforts of these organizations culminated in the Southwest Association on Indian Affair’s Indian Market, and even today, Indian Market determines to a great extent the direction and sales of Indian art.

These organizations were, of course, extensions of the larger American/ Western world. The values which they assumed and operated from were very different than those of the Pueblo world. Therefore, the effect that these organizations had on the process of Pueblo pottery making was tremendous. I will discuss three major ideological shifts that were stimulated by these organizations and give examples of how they are expressed in the pottery-making process.

Shifting Values

Individualism or the focus on the self and one’s own product—or pot—was strongly emphasized by these outside organizations. Communally or group production of pottery declined as the Pueblo people began to sign their names on pots, as was encouraged by these outsiders. Individual ownership of pots precludes the interactive process of the old way. One woman at Santa Clara states it this way:

At that time their behavior with prayerful talking caused the clay to purify itself. She purifies herself to give good luck to the individuals. If they do it the right way-hut today we are crazy—sometimes we must go for it and bring it home and Clay-old-lady feels some way [bad] and mixes things into herself…they tell you not to misuse the clay. When clay fell they did not sweep up the clay with a vacuum cleaner. They would pick it up and take it outside and automatically it would go back to where it came from. Now we pick it up and we throw it around like trash and the Clay-oldlady feels some way and that’s why she doesn’t purify the clay.

Courtesy Museum of New Mexico, neg. no. 4171. Photo by T. Harmon Parkhurst

These Anglo organizations, prizes were awarded to potters whose pots were more pleasing to the organizations’ handpicked judges, whose values matched their own. Competition is contradictory to traditional Pueblo thought. It is, of course, an exclusionary act which dilutes interaction. For instance, one-man shows, here as elsewhere in the art world, are an indication that the artist has “arrived.” It is uncommon for older Pueblo potters to be featured in one-man shows. One of the major criteria for granting a one-man show is the Western value of technical excellence. The older potter is generally making pottery for the act of making it as well as for the income. Middle-aged and younger potters opt, for reasons of economic enhancement and individual recognition, to pursue the technical excellence that will lead to one-man shows. Thus individual pursuits are seen as more important than interactive ones.

Competition, furthermore, leads to the pursuit of perfection. Pots, as an extension of everyday living in the old Pueblo world, were spontaneous acts of creation to meet functional or ceremonial needs. It was recognized that perfection also excluded interaction. Older potters most often believe that the pottery cannot impose perfection onto an interactive process. An older potter states it this way:

What’s perfect? You can’t do it! We were younger then, and old folks used to talk and they always say ‘there’s nothing perfect—unless a White man makes it with a machine. But an Indian, he believes in himself with his clay. You got faith in what you’re doing with that pottery, with mother earth. The Clay-lady makes it hut there’s no machinery.’

These are major changes. Individualism, competitiveness, and the pursuit of perfection today set the stage for the economics of Pueblo pottery making. Economics take us—Pueblo people—solidly into the Anglo-American world and further from that old world where clay is sacred, where Nung-ochu-quijo is considered alive, where we flow with her and where we need to breathe as a partner with her.