Pueblo people of the American Southwest say that as long as there is Pueblo religion there will be handmade cloth. For many Pueblo textile artists, the practice of making textiles is like the breath of life itself, actively sustaining their Pueblo identity, one stitch at a time.

Although embroidered garments and decorative textiles are most visible to outsiders at annual public feasts that mark the hybrid Christian/Pueblo calendar—where hundreds of dancers move onto the plazas wearing colorfully embroidered manta dresses, kilts, hand-woven belts, and sashes— they serve many different purposes in Pueblo communities today. For example, textiles are also used to dress and bring focus to important non-human entities. During religious processions, Pueblo cloth creates a temporary sanctuary or bower to house the patron saints of many villages whose carved icons are carried from the church onto the plazas each year. On these occasions, animals such as deer, elk, buffalo, and mountain lions placed in or near the bower are honored with cloth as well. Similarly, textiles dress the Canes of Office of the Pueblo Governor on All Kings Day, in January, when newly appointed governors are installed.

Each of these examples illustrates how Pueblo cloth creates a focused space of honor. Whether worn on the body or used to define special objects or spaces, Pueblo textiles mark sacred domain. As woven expressions of place, prayer, and cosmos they transform and engage Pueblo people in relationships with the world around them. Pueblo cloth plays an active and meaningful part in the construction of Pueblo life, bringing blessings of harmony, strength, and happiness into the Pueblo world. But above all, Pueblo textiles are beautiful—they sing with color and brightness and bring smiles to Pueblo people’s faces. Shawn Tafoya has written about Pueblo textiles in the following way:

They are the clothing of the gods and dancers,

They are the clothing of our sacred spaces,

our holy places, our homes, and us.

They are symbolic and full of meaning,

They are powerful and sacred,

They are beautiful.

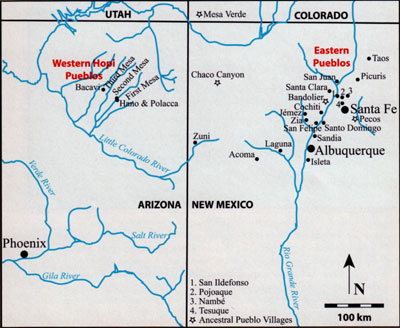

The Eastern Pueblos

The Eastern Pueblos of the Rio Grande and Jémez Mountain valleys consist of 17 communities in central New Mexico that are home to speakers of three distinct dialects of the Tanoan language family—Tiwa, Tewa, and Towa—as well as Keresan. This land has long been inhabited by their ancestors, and Pueblo origins, histories, religion, and their agricultural way of life are intricately tied to the landscape. Jémez Pueblo scholar Joe Sando has written that the basic concern of Pueblo religious life is the continuity of the harmonious relationship with the world in which they live and the maintenance of relationships between the people and the spiritual world. Pueblo textiles are material expressions of these commitments and, not surprisingly, relate closely to the landscape in which Pueblo people live.

Pueblo craftsmen have woven baskets and textiles for over 2,000 years. Predominantly made of indigenous cotton, their garments were hand spun and then woven in a balanced plain weave, and they were often decorated using dyeing, painting, or tie-dyeing techniques. Possibly as early as AD 1100, archaeological evidence in the Rio Grande region suggests that weaving was done on upright looms, possibly by both men and women, with men increasingly weaving cotton garments in ritual settings after AD 1400.

With the arrival of Spanish colonists in the 16th and 17th centuries, catastrophic changes afflicted Pueblo communities, particularly in the eastern villages close to the Rio Grande. Decades of extraordinary hardship and loss saw Pueblo families forced to pay tribute in the form of woven cotton blankets (mantas) and knit wool stockings made from sheep introduced by the Spanish. During this period, Pueblo women— who were allowed to retain their traditional dress by Franciscan missionaries—took on more of the textile arts to meet these demands. This enforced encomienda tribute system continued until 1680, when Pueblo people across the region united in successful rebellion and regained their sovereignty. Although the Spanish returned 12 years later to continue their colonial enterprise, Pueblo people continued to fight to retain the core of their religious and cultural ways alongside those of the Catholic Church.

Today, Pueblo people speak of their textiles as clothes of the spirits. With its roots in the earth and stalk and pods in the sky, the cotton plant links earth and sky together. Pueblo textiles are best understood as devoted acts of prayer for rain and wellbeing. Pueblo garments actively wrap the wearer in signs that communicate connections to the Pueblo world. In so doing, cloth directly engages, strengthens, and shapes the wearer’s very being, his or her thoughts and actions. Through song, dance, and prayer, each participant is a contributing act of devotion within the larger Pueblo cosmos.

Two Eastern Pueblo Embroidery Artists

Although many people are familiar with Western Hopi Pueblo communities as sources of traditional woven and embroidered cloth, textiles from the eastern Rio Grande and Jémez Mountain valleys in New Mexico are less well known. During recent visits to the Tewa villages, two contemporary embroiderers, Isabel Gonzales and Shawn Tafoya, agreed to share their understanding of the textiles of these Eastern Pueblo communities. Both are well known for their traditional embroidered garments used in Pueblo ritual, as well as for their innovative, secular textiles that use new forms and designs. Conversations with Shawn and Isabel enrich our understanding of the legacy of Pueblo embroidery and the vitality with which this important expression of Pueblo identity continues to be made and used in Pueblo communities today.

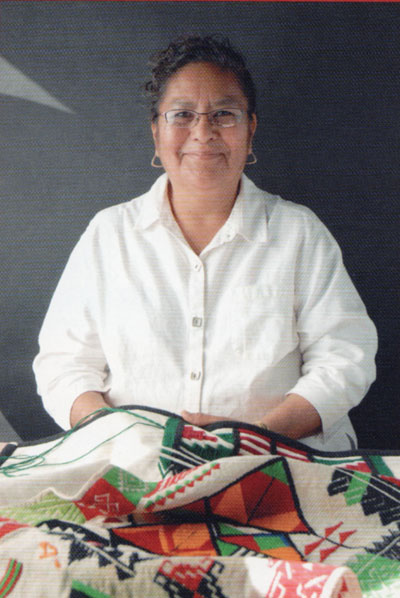

Isabel Gonzales

Isabel Cajero Gonzales was born in the Towa-speaking mountain village of Walatowa, or Jémez, located 60 miles west of Santa Fe. A member of her mother’s Badger Clan of the Pumpkin moiety, one of Isabel’s names is Paa-Kuu-la, which means “Colorful Mountains.” As a young woman Isabel married into the Tewa-speaking village of Powhogeh (“village where the water cuts through”), located 30 miles north of Santa Fe and also known by its Spanish name of San Ildefonso. She and her late husband, Raymond Gonzales, raised their four children at “San I,” and today Isabel cares for several of her grandchildren there. She also maintains a myriad of relationships and community obligations with her large family at Jémez. As a result, Isabel regularly moves in an ongoing and busy network of activities between these two communities.

Throughout her life, embroidery has been a cornerstone of strength and identity and a creative process that brings balance, calm, and meaning to Isabel’s busy and active schedule. Isabel travels frequently to teach embroidery and she exhibits her textiles in many art shows and museums. Her most important commitment, however, is to her Pueblo people. She regularly receives orders from individuals throughout the villages and works hard to fill these requests by the dates specified. Her embroidery style remains traditional to Jémez, where she was taught by her mother, Loretta, and instructed to keep her needlework true to the old forms. On some garments, therefore, she limits her embroidery color palette largely to red, green, and black. Color is a meaningful and fundamental organizing principle for all Pueblo people and a way of classifying the world. At Jémez, red, green, and black are associated with the seasons, cardinal directions, and cosmological principles.

One of Isabel’s signature pieces is the embroidered dance kilt, called kei–té in Towa. These garments are an icon of Pueblo identity and Isabel receives orders for them from individuals in many different villages. Each kei–té takes her two to three weeks to produce. Today, they are made from a rectangular piece of monk’s cloth, a commercial cotton cloth woven in a plain or “balanced” weave. To add embroidered designs, Isabel uses commercial wool yarn, which she re-spins by hand to tighten it before sewing. Designs on kei–té represent different forms of water moving on the landscape, such as rain clouds, falling rain, and fog, as well as mountains, plants, and references to the dance plaza—the center of every Pueblo community. Although Isabel’s kei–té are always traditional in overall form and color, they are creative and innovative in prescribed areas.

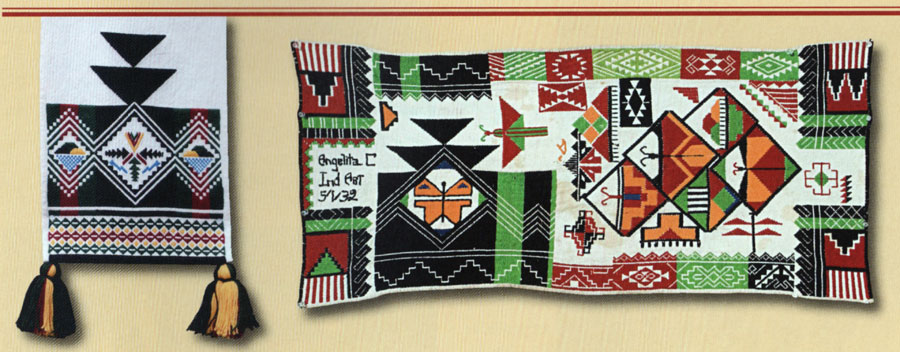

Right, as a young woman, when Isabel began to take on more difficult embroidery projects, her aunt, Lupe Sando, supported her commitment by passing down her own late daughter’s sampler. This sampler, now a favorite piece in Isabel’s personal collection, was made in 1932 by her cousin, Angelita Cajero, when she was a student at the Santa Fe Indian School. By 1930 this federal, off-reservation boarding school emphasized the preservation of traditional native arts and taught students Pueblo weaving and embroidery. The designs on Angelita’s sampler include clouds (in the corners), dragonflies, and at least four different styles of butterflies. It also contains a number of geometric motifs which, out of respect for the preservation of her culture and religion, Isabel prefers not to identify. “Pueblo knowledge is contained in cloth, not on paper, and it is not appropriate for me to share that kind of information . . . . I am so honored to have Angelita’s sampler. I never imagined I would have such a beautiful piece. She put a lot of thought into it, not knowing who would have it in the future. Right now it is meaningful because of the designs she has put on there. I can go to this to carry on my work for the next generation. Because of this, Pueblo embroidery is never going to get lost; it will always be there for us to come back to and to look at as a source of design.”

Making her living from her embroidery, Isabel has taught and inspired many students at Pojoaque Pueblo’s Poeh Center, Bandelier National Monument, the University of New Mexico, and at the Third Mesa Hopi village of Bacavi. She also shows and sells her work publicly at annual fairs including Santa Fe’s Indian Market, the Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair and Market in Phoenix, and the Annual Red Rocks Art and Crafts Show at Jémez Pueblo. Farther from home, her work is represented in the collections of the National Museum of the American Indian, the Penn Museum, the White House, and the Museo do Índio in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. In addition, her textiles have been given as gifts by Pueblo governors to indigenous presidents in Brazil and to President Evo Morales of Bolivia. In all of these contexts, Isabel’s embroidery expresses her personal spirituality and commitment as a role model in support of traditional Pueblo values and the centrality of place and community for Pueblo people.

Shawn Tafoya

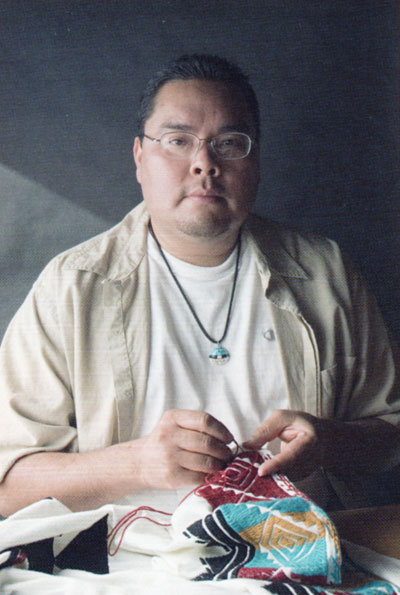

Shawn Tafoya, another prominent embroiderer, is a member of the famous Tafoya family and comes from a long line of artists and craftspeople. In his late thirties, he is the son of Lucy Year Flower of Pojoaque Pueblo and Joseph L. Tafoya of Khap’p’oo Ówingeh (“singing water”), known by its Spanish name of Santa Clara Pueblo. Shawn creates both traditional and innovative embroidered pieces and has received numerous prestigious awards, such as the Dubin Fellowship at the School of American Research (Santa Fe), and awards at the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts’ (SWAIA) Indian Market and at the Eight Northern Pueblos Crafts Fair, which takes place in the Tewa villages in July of each year.

Like Isabel, Shawn actively supports traditional Pueblo ritual and religion through the creation of embroidery. He is also an active and accomplished potter. A member of the Corn Clan and Winter moiety, Shawn regularly participates in his ceremonial kiva’s dances and activities and prepares ritual dance attire for his family and other members of his community. On important occasions he is often responsible for dressing the female participants. He is admired by his brothers, sisters, nieces, and nephews, and is a strong role model and teacher.

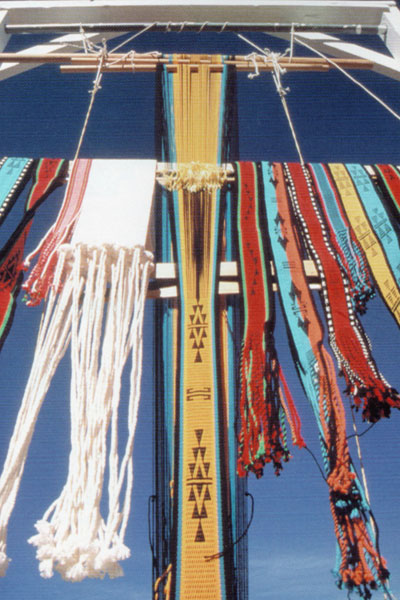

Shawn has been making embroidered and woven garments for 20 years. In Pueblo society, men are often weavers and embroiderers and, as a small boy, he remembers being drawn to the old textiles in his family’s collection. Like Isabel, Shawn’s work is among the finest produced in the Tewa communities today. Largely self-taught, he tightly re-spins the commercial cotton, wool, and acrylic yarns that he purchases for his work. Preferring to work late into the night, he has a unique way of burying the ends of his embroidery stitches and of finishing his pieces, which give them a crisp and polished elegance.

Right, entitled Puganíní, “Pueblo Butterflies,” this wall hanging has three animated butterflies embroidered within its central diamond motifs, surrounded by a multitude of others that are painted on the cloth’s surface. “Butterflies are one of the favorite designs of the Pueblo people,” notes Shawn. “They are found on everything from pottery to textiles, baskets, dance headdresses (tablitas), and paintings. They bring happiness and joy into the world. The butterflies on this wall hanging include designs from all Pueblo communities, including Hopi.” He splattered additional pigment to represent mist and motion. This piece was influenced by Shawn’s experience as a potter as well as his avid interest in his ancestors’ ancient decorative textile techniques. It expresses Pueblo narrative history and tradition in new and unique ways.

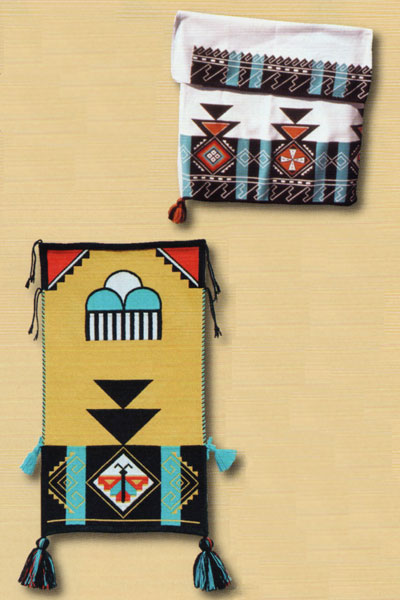

Left, this wall hanging, entitled Kwan tsáawä, or “Blue Rain,” is used to create a kind of special, sacred space, and pieces like it are often used for All Kings Day celebrations around the first of the New Year when new tribal governors are

installed into office. Hung on the wall, this cloth creates the appropriate space with which to frame the Governor’s canes of office that reside in the Governor’s home while they are blessed on that special occasion. The design elements on the piece include a Santa Clara-style butterfly with winter clouds of red and white, yet on a yellow background of summer. The small blue bows on the sides honor blue butterflies and blue flowers and the tassels represent corn. The geometric outlined design in yellow and blue in the lower portion of the piece represents hooked bird beaks bringing summer rains to the pueblo. The textile in its entirety is a prayer for rain.

Shawn’s traditional embroidery is serious, meticulous, reverent, and impassioned. Garments include embroidered white mantas, or segá, dance kilts, breechcloths, and hand-woven sashes, all of which are worn by men and women in a variety of ways on ceremonial occasions.

“Like words,” he notes, “Pueblo textiles and embroidered designs can be broken down into elements, or put together to create broader meanings.” Like language, the combining and layering of design motifs and cloth communicate different meanings within different contexts.

In addition to his traditional textiles used in Pueblo ritual, Shawn creates colorful and creative pieces that are unusual and often playful. This work has a narrative quality that honors Pueblo history and the importance of relationships, and a painterly quality that extends from his work as a potter. For example, Shawn’s embroidered wall hangings embody stories about Santa Clara’s relationship with the Hopi. Through design, technique, and imagery, these textiles bridge both time and space and tell stories about Santa Clara’s strong historical connection with the Tewa-Hopi who live at First Mesa Villages in Arizona. To this day, many Santa Clarans honor this relationship by traveling to Hopi to dance, and occasionally the Tewa-Hopi travel to Santa Clara where they help as well. According to Shawn, the details of both group’s dances have changed over time and today are a combination of Rio Grande and Hopi Pueblo styles.

Raised in a community where artistic tradition as well as innovation is revered, Shawn’s most innovative textiles continue to raise hope and expectations and to bring smiles to Pueblo faces.

Eastern Pueblo Textiles

Best understood within the contexts in which they are made and used, contemporary Eastern Pueblo textiles continue to hold meaning and purpose in Pueblo communities today. Though not all of these meanings can be shared, embroidered garments are an important material expression of Pueblo identity, and textile artists would like this to be recognized. Conversations with contemporary embroiderers enrich our understanding of the language, meaning, and beauty of Pueblo cloth. Embroidered garments are enduring material expressions of commitment to Pueblo identity and ideology. They are fundamental acts of prayer that conceptualize the Pueblo landscape and relationships to the spiritual and natural worlds. Textiles create and illustrate sacred spaces and record and reenact Pueblo narratives and histories. In addition, textiles serve as important sources of economy for Pueblo artists and circulate within and outside Pueblo communities, linking families, clans, and outsiders in unique ways. When sold to collectors and museums, Pueblo textiles leave their home contexts to function in different realms, as expressions of the work of individual artists and as markers of Pueblo culture. Their creation and use within Pueblo communities today continues to facilitate practices of Pueblo religion and bring beauty into the world.

We Pray While We Work

We pray while we work knowing that

what we do is sacred and special.

As we begin we ask for guidance from our ancestors,

who long ago sang Pueblo embroidery into being.

As we embroider we remember the shapes

and colors of our ceremonies,

the shapes and colors of the landscape.

As we work we sing life songs into our embroidery pieces,

knowing that they will embody

all of our thoughts and prayers.

To this end we bring forward this day a new life being.

Give us good fortune and bless us with a long and happy life.

That is what we say to our embroidery pieces!

Gonzales, Isabel C. “The Face of a Community.” In Native American Voices on Identity, Art, & Culture: Objects of Everlasting Esteem, edited by Lucy Fowler Williams, William Wierzbowski, and Robert W. Preucel, p. 183. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2005.

Kent, Kate Peck. Pueblo Indian Textiles: A Living Tradition. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research, 1983.Mera, Harry Percival. Pueblo Indian Embroidery. Santa Fe, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1943.

Sando, Joe S. Nee Hemish: A History of Jémez Pueblo. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1982.

Suina, Joseph H. “The Persistence of the Corn Mothers.” In The Pueblo Revolt, edited by Robert Preucel, pp. 212-16. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2002.

Tafoya, Shawn. “Thoughts from a Santa Clara Pueblo Traditional Embroiderer.” In Native American Voices on Identity, Art, & Culture: Objects of Everlasting Esteem, edited by Lucy Fowler Williams, William Wierzbowski, and Robert W. Preucel, p. 55. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2005.

Webster, Laurie D. “Effects of European Contact on Textile Production and Exchange in the North American Southwest: A Pueblo Case Study.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Arizona, 1997.