Tutankhamun, ancient Egypt's famous boy pharaoh, grew up 3,300 years ago in the royal court at Amarna, the ancient city of Akhet-aten, whose name meant the "Horizon of the Aten.” This extraordinary royal city grew, flourished—and vanished—in hardly more than a generation’s time. Amarna, Ancient Egypt’s Place in the Sun, a new exhibition at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Philadelphia, offers a rare look at the meteoric rise and fall of this unique royal city during one of Egypt’s most intriguing times. The exhibition, which opened in 2006, originally scheduled to run through October 2007, has been given a long-term extension, as a complement to the Museum's refurbished Upper and Lower Egyptian galleries.

With background information about the childhood home and unique times in which Tutankhamun lived, Amarna is a complementary exhibition to the nationally traveled, blockbuster exhibition from Egypt, Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs. Penn Museum is partnering locally with The Franklin Institute, which hosts the blockbuster Tut show beginning February 3, 2007.

Located in a previously uninhabited stretch of desert in Middle Egypt, Amarna was founded by the Pharaoh Akhenaten. His wife, Queen Nefertiti, is still known worldwide for her exquisite beauty. She was not the mother of Tutankhamun, but it is likely that Akhenaten was his father. Sometimes referred to as Egypt’s “heretic” pharaoh, Akhenaten radically altered Egypt’s long-standing, polytheistic religious practices, introducing the belief in a single deity, the disk of the sun, called the Aten. With the new religion came a dramatically new artistic style, one characterized by more naturalistic figures, curving lines, and emphasized gestures. The new era, however, proved short lived—by the time that Tutankhamun died, at about the age of 19, hardly a decade into his kingship, the “Amarna Period” was not only coming to an end, but the Egyptian people’s traditional beliefs and religious practices were being restored. Plans were also underway to abandon and dismantle the city. Monumental wall relief (E16230) of the royal family worshipping the Aten, possibly from Amarna, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE), quartzite Central to the exhibition is a monumental wall relief depicting the solar deity Aten as a disk hovering above the pharaoh Akhenaten and a female member of the royal family. The Aten’s rays descend toward the figures, each terminating in a hand. Some time after the restoration of the traditional religion, this relief was cut down, placed face down on the ground, re-inscribed, and reused, probably as a base for a statue in the shape of a sphinx for the later pharaoh Merenptah (1213-1204 BCE). Ironically, this recycling accidentally preserved the decorated front of the relief from total destruction.

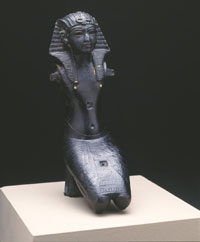

Other highlights from the exhibition, housed in two gallery rooms off the Museum’s Lower Egyptian gallery, include two statues that probably represent Tutankhamun: a bronze kneeling statuette and an elegant standing figure of Amun with Tutankhamun’s features. The latter statue is an indication of Egyptian religion reverting to traditional presentations connecting the king and the god Amun at the head of the pantheon. Other statues of traditional gods in the exhibition include the lioness-headed goddess Sekhmet and the mother-son Isis and Horus. Personal items of ancient royalty—a seal and a scarab of Amenhotep III, vessel fragments bearing cartouches of queens Nefertiti and Tiye, a comb, an elegant statue of an Amarna princess—remind the visitor of the individuals who lived at that time. An ancient wooden mallet, fiber brush, unfinished statue and decorative molds for the making of glass items speak to the presence of a vibrant artisan community. More than a decade before British archaeologist Howard Carter discovered Tutankhamun’s extraordinary tomb in the Valley of the Kings, American explorer Theodore Davis found a nearby pit that contained vessels from the boy king’s funerary feast, among other things. Some of those ceramic pieces also will be on display. Amarna is designed by the McMillan Group, designers of the Los Angeles installation of Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs. Amarna, Ancient Egypt’s Place in the Sun is co-curated by Dr. David Silverman, the Eckley Brinton Coxe, Jr. Professor and Curator of Egyptology; Dr. Jennifer Wegner, Research Specialist, Egyptian section; and Dr. Josef Wegner, Associate Curator and Professor in the Museum’s Egyptian section. All three curators also teach in the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Arts and Sciences. Amarna, Ancient Egypt’s Place in the Sun has been made possible with the lead support of The Annenberg Foundation; Andrea M. Baldeck, M.D., and William M. Hollis, Jr.; Susan H. Horsey; and the Frederick J. Manning family. Additional support was provided by the Connelly Foundation, the Greater Philadelphia Tourism Marketing Corporation, IBM Corporation, Mr. and Mrs. Robert M. Levy, Margaret R. Mainwaring, and The National Geographic Society. In time for the opening of the Amarna exhibition, Penn Museum’s renowned Upper and Lower Egyptian galleries, will be refurbished. The galleries offer visitors an opportunity to view a wide variety of ancient Egyptian artifacts from several millennia. Materials range from monumental architecture to sculptures, pottery, jewelry, tomb goods, and mummies.

*A new publication from Penn Museum Publications:

by David P. Silverman, Josef W. Wegner, and Jennifer Houser Wegner |

Amarna, Ancient Egypt’s Place in the Sun features more than 100 ancient artifacts, some never before on display—including statuary of gods, goddesses and royalty, monumental reliefs, golden jewelry as well as personal items from the royal family, and artists’ materials from the royal workshops of Amarna. Most of the show’s artifacts date to the time of Tutankhamun and the Amarna Period, including many objects excavated almost a century ago from this short lived-royal city.

Amarna, Ancient Egypt’s Place in the Sun features more than 100 ancient artifacts, some never before on display—including statuary of gods, goddesses and royalty, monumental reliefs, golden jewelry as well as personal items from the royal family, and artists’ materials from the royal workshops of Amarna. Most of the show’s artifacts date to the time of Tutankhamun and the Amarna Period, including many objects excavated almost a century ago from this short lived-royal city.

Akhenaten

& Tutankhamun:

Akhenaten

& Tutankhamun: