It is generally taken for granted that Museum expeditions, archaeological or ethnological, will be productive of tangible results, of objects that illustrate the life of the people studied, past or present. Here they are preserved, mute deponents to the nature of the cultures of past peoples and of exotic present ones.

But, just as it is the purpose of museums to preserve the material relics of vanished and vanishing peoples, so also is it their duty to conserve, by means of records, the non-material phases of alien cultures, their customs, folklore, and especially their languages. And the latter is far more urgent than archaeological investigations. The objects have lain in the ground for centuries or millennia, and could remain there many more. But the customs and the languages, with thousands of years of historical development behind them, are, in these days, rapidly disappearing and being replaced by those of European derivation. Once gone, they arc unrecoverable; they cannot be dug up or reconstructed.

Languages in particular are strong clues to the history of a people. If the languages of two distantly separated tribes or nations are related, it means that at one time they were adjacent, or one people, and so their movements and migrations can be traced. The same is true, but to a lesser extent, of customs and folklore, for these change much more quickly. Except for physical type, nothing is so constant as language; it changes-but slowly.

Language is such a natural feature of mankind that few people ever give it any thought, and most of their ideas on language arc misconceptions. To the average person, a foreign language is something printed in a book, but languages have been spoken for untold thousands of years; their writing has a history of only five thousand or so. The great majority of languages in the world have never been written.

The average concept of a great linguist is one who knows something of-or can speak-Latin, Creek, English, French. German, and possibly Italian and Spanish. These languages are all related, members of the same family, descended from one parent speech, and having a similar grammatical mechanism. In fact, there are only two or three languages in Europe that belong to other linguistic families, not related to the above-named: Basque, and the Finno-Ugrian languages, such as Finnish and Hungarian. But in America alone there were probably over a thousand mutually unintelligible Indian languages, in possibly a hundred and fifty separate and unrelated linguistic families, though, doubtless, the number of independent families will be greatly reduced after we know more about them and are able to compare them. And yet the “man in the street” generally thinks of the Indian language!

It is estimated that in the world there are now about two thousand mutually unintelligible languages, of which relatively few have been reduced to writing. America, North and South, is the region of greatest linguistic diversity, and probably contains nearly half of this number. In some regions the diversity is incredible. There are-or were-for instance, many more separate languages in California than in all Europe. John H. Rowe has just announced that in a linguistic survey of Colombia he counted eighty mutually unintelligible languages belonging to over twenty apparently independent and unrelated families. These are the living languages, and more than fifty have become extinct since the Spanish conquest.

Research in American Indian languages, especially in South America, is one of the greatest desiderata of anthropological research. Many of them are on the verge of extinction, spoken by only a dozen persons. Of many of them we know only that they exist. From others we have, often, a vocabulary of only forty or fifty words, made by some traveler without any linguistic training. And only in 1941 the greatest and most reliable Brazilian ethnologist, Curt Nimuendajú, announced his discovery in a small region in eastern Brazil of five new languages different from any other known to him. And yet, on this basis, a few years ago I had to attempt a classification of South American Indian languages!*

There are no “primitive” languages; there are only languages of non-literate peoples. The idea that these languages consist mainly of grunts, that they are unable to express many concepts, is radically wrong. There is no language not perfectly adequate to express any sentiment that a speaker might want to convey. Of course the savage has no single word for “atom” or “isostasy,” but if he had to explain the concepts in his language he would have no difficulty in doing so.

In fact, many of the languages of non-literate peoples are far more complex than modem European ones. In its main grammatical outlines, English is one of the simplest languages in the world, probably the next simplest after Chinese. It has found the processes of Anglo-Saxon – such as grammatical gender and inflection – superfluous, and has thrown them away. And it would be a better language yet if it would throw the rest of its grammar away – as Chinese has. After all, a language is primarily a mechanism for expressing thought, and, like all machines, the fewer gears and cams it has, the better the instrument.

For, strange to say, the present course of evolution in languages seems to be just the opposite of biological evolution; they tend to evolve-or retrograde-from the complex to the simple. Of practically all the languages of which we have historical record, such as Latin, for instance, the modern descendants-Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French, in this case – are grammatically simpler than the parent. Of course there must have been a time when grammars were building up, but that time was early in human history, maybe hundreds of thousands of years ago; of that period we know nothing.

And so, just as living primitive peoples more or less illustrate the life of our European ancestors of several thousand years ago, so their languages possibly roughly represent the type of speech of paleolithic Europe. All we can say is that, typically, their grammars are much more complex: they often have more genders, numbers, persons, tenses and modes-especially the latter-than any modern language.

These languages have no uniform-or approximately uniform-grammatical pattern, such as we are accustomed to in all well-known European languages; they differ immensely. As an illustration of how they work, however, I might give an example from one of the languages on which I have been working, the Tepehuan, a little-known language of the mountains of northern Mexico, spoken by a few natives and rapidly disappearing.

Suppose a speaker of this language were to say to another the word mai-ti-pe-shi-a-t-a-duni-a. (I normalize this a little to English spelling, and divide the elements by hyphens.) It is a single word, for no part of it is used independently, any more than “ess” is in English, but -ess may be suffixed to “host” or “patron,” where it means “feminine.”

The hearer would understand from this, more or less, the following sense: “Don’t you want to work on this job a little?” I haven’t yet finished my study of this language, and am not quite certain of the meanings of some elements, but it is somewhat as follows.

The word seems to consist of nine elements. mai is a sort of introductory, designating some types of clauses and phrases that are not statements, and ti may be a kind of subjunctive sign, indicating uncertainty. pc is the pronoun “thou,” second person singular. shi is the interrogative, making it a question. a is apparently the desiderative, indicating volition. t is the “punctual” sign, indicating that the action is rather brief. This is very important in the languages of this group, which stress the division between actions that have considerable extension in time or space and those that have little. a is a “referential,” referring to something understood – in this case, the job. duni is the heart of the word, the verb root, meaning “to work,” and the final a is one of several elements indicating various phases of future tense.

Now there are other pronouns, tense signs, and many modal elements that can be used in place of, or in addition to, the above in combination with the verb root duni, ”to work,” or “to do,” so that the possible permutations, the possible paradigms of this verb would probably number many thousands.

Logically, there is a good deal to be said for languages that work like this one, in which the verb may be modified in thousands of ways to express various shades of meaning. Such languages can obviously get along with relatively few verbs of generalized significance. It is, of course, silly to compare the number of verbs in such a language with those in English, where each one must have a very definite and specialized meaning. It would be easy to invent an artificial language on the pattern of “primitive” ones which would theoretically be an excellent one. But languages are living mechanisms and, as I said before, they all seem to be giving up their former complex grammars in favor of unchangeable definite words.

How old is the Tepehuán language? The scientific answer would be – just as old as every language, as old as human speech. For what’s in a name? Is modern Creek really an older language than Spanish merely because we still call it Greek while we call the several forms of modern Latin French, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese? Modern Greek has changed as much from the classical form as Italian has from Latin. Despite the protests of purists who cry out against all innovations and want to keep their language in its present “purity,” all languages change slowly, as they always have, until their forms become sufficiently differentiated to be called separate languages. And so, at the beginning of the Christian era, the ancestors of the Tepehuán Indians spoke an earlier form of their language, probably as different from the modern one as Latin was from Spanish. Only we have written records of Latin while we can never know much about the Tepehuán language of A.D. 1.

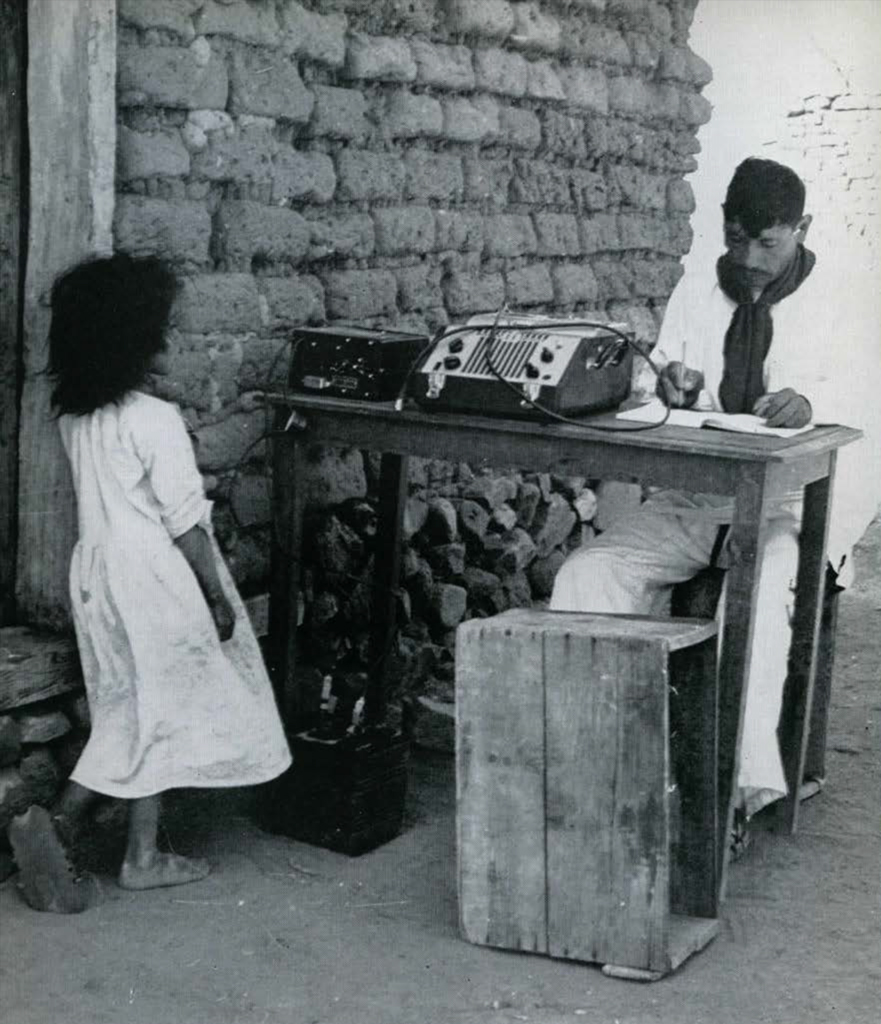

Even more than the archaeologist or ethnologist, the investigator of the languages of aborigines needs special training. The language must be written down, and the grammar worked out. Modern types of recording machines, wire and tape recorders, are of great help in this work but, of course, merely record the speech for future generations and give auditory proof of the phonetics; they are useless for working out grammar. Some light, portable recorders are now made, operating on dry batteries, but to work with the ordinary heavy office type, as I have always done, entails considerable practical difficulties. Unless the native can be brought to some place where electric current is available, a converter to change from direct to alternating current must be taken along, as well as several automobile batteries. When the latter are exhausted, unless they can be sent to be recharged, end to the work! As the last battery begins to weaken, one begins to figure how much more work can be done and still have enough current left to rewind the wire or tape back on the spool. For, without current, it must be about a day’s work to rewind by hand a mile of wire back on the reel. In the last event, a little rest and heat in the sun will often give the battery enough reserve power to complete the rewinding job.

Then, too, if one is working with a wire recorder, the hair-thin wire, escaping from the reel, will sometimes get down and snarled in the mechanism; then it’s several hours of work to cut it out and tie the wire ends together again.

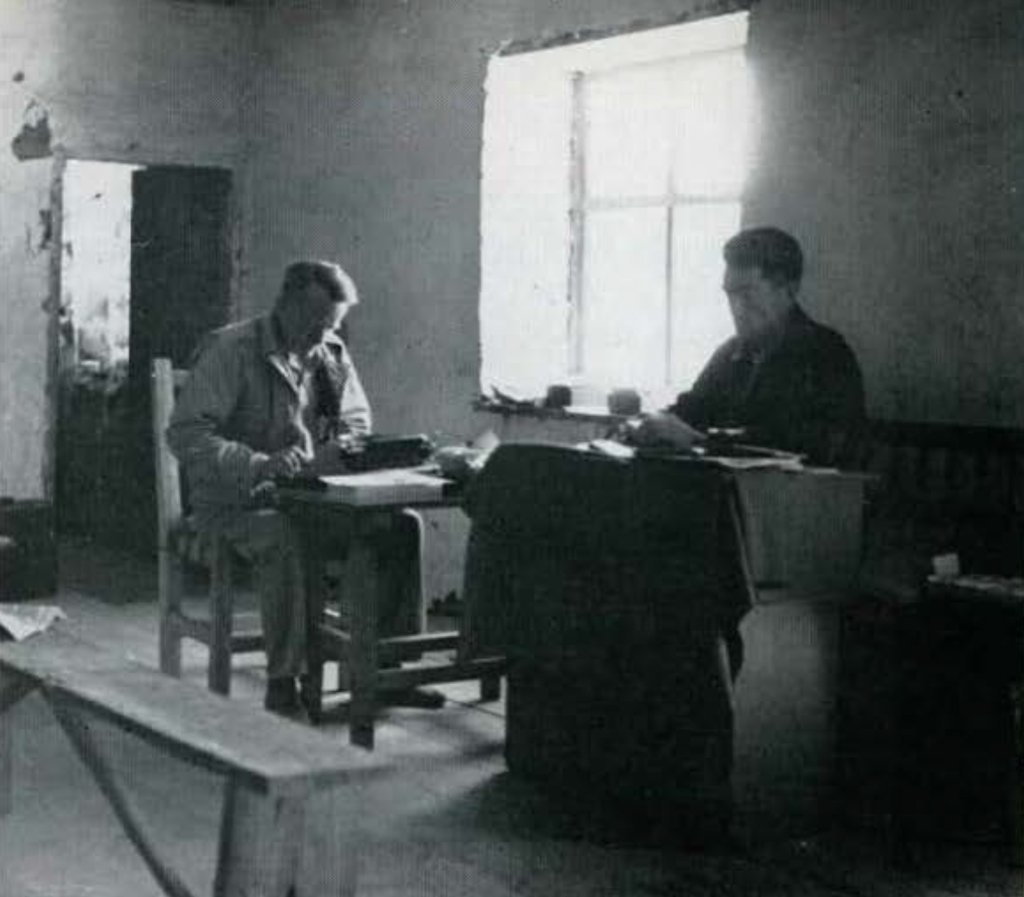

In order to work out the grammar, the text, preferably exactly as mechanically recorded, must be written clown and accurately translated to English, Spanish, or any language common to the informant and the investigator. This is the longest part of the job. To get the text exactly as it was spoken into the recorder, the latter must be played, a phrase at a time, over and over. “No, that isn’t exactly what you said to the machine. Listen again and repeat exactly!” After many hours of such work, if your tired, bored and irritated informant hasn’t thrown up the job and run away, you get it down on paper and translated. Then, following clues that you have gotten during this work, you ask “How do you say ‘He went’? ‘Go!’ ‘They wouldn’t go.’ ‘I wish I’d gone.’ ‘We couldn’t go.'”

The aborigine, of course, has no more concept of the workings and details of the grammar of his language than has the uneducated speaker of English or of any other well-known language; he merely speaks and understands it as a matter of habit.

The writing clown of a new language is no amateur task and needs training in phonetics. Missionary groups are now engaged in reducing to writing many languages that have never before been written down. Their purpose is of course to teach the natives to read, and for this they need to develop a simple orthography. The anthropological linguist uses a more complicated one with many diacritical marks to show tone, length of vowels or consonants, accent, and other such things. Most Indian words written clown by untrained travelers are almost worthless, because each one uses the orthography of his own language which is unfitted to record any other one. English, with its unphonetic and silly spelling, is one of the worst. For instance, we put an unpronounced e on the end of a word, or double a following consonant, to show the difference between preceding close (long) and open (short) vowels, as bite and bit, filing and filling.

Every person is inclined to think of the sounds in his own language as being the only natural and normal ones, of minor variations as “foreign accent.” Some phoneticians have figured that the human speech mechanism is capable of producing some fifty thousand distinguishable sounds. Many of these are theoretical and found in no language; many more are extremely rare. But no language employs over about fifty of these. English has forty-one, above the average. In speaking and writing a foreign language a person is usually inclined to assimilate a foreign sound to its nearest equivalent in his own language, but it is a rare sound that is exactly the same in two given languages. And what is the person who uses only English orthography to do when he comes up against a language that distinguishes two or three different kinds of t’s or l’s?

So the student of linguistics has to be trained in phonetics. He has to analyze every sound, determine where and how it is articulated, note the quality of tenseness or looseness, the length, the tones of vowels, nasalization, amount of aspiration, and many other qualities, and develop an alphabet to fit the language, one that distinguishes every basic sound and never confuses it with another.

Finally, after several weeks of work, you think you have all the necessary data down, and go home. Then follow months of desk work, determining the roots or stems of verbs, nouns and adjectives, and the meanings of the particles that modify them. The true linguist gets as much “kick” out of tying down the significance of a grammatical particle as the archaeologist does out of digging up a new type of object. It was never done before-a new discovery!

The University Museum has had a long tradition of research in linguistics, especially in American Indian languages, though it has never specialized in this field. One of our great pioneer founders, Dr. Daniel Garrison Brinton. the first anthropologist to call himself an Americanist, was primarily a student of Indian languages, did much of the early and fundamental work in this line, and published many articles on American languages, most of them based, however, on old published work rather than on field research. One of the great founders of the science of modern linguistics, the late revered Edward Sapir, began his career here as an instructor. Unlike Brinton, he got his experience investigating living Indian languages. The Museum published two works of his in our series of Anthropological Publications: “Takelma Texts” (Vol. II, No. 1, 1909), and “Notes on Chasta Costa Phonology and Morphology” (Vol. II, No. 2. 1914). Dr. Frank G. Speck who, in early days, was on the Museum staff and had his office in the building, also included linguistics among his varied interests, knew several Algonkian languages or dialects well, and also had a good knowledge of Iroquois, Cherokee, Catawba, Yuchi. and several other Indian languages.

Both Sapir and Speck had been students of the late Franz Boas who followed Brinton as the great authority on American Indian languages, and our Anthropological Publications is honored by having in it one of Boas’ writings, “Grammatical Notes on the Language of the Tlingit Indians” (Vol. VIII, No. l, 1917). And, apropos of the Tlingit, a late long-time Assistant Curator in the American Section, Louis Shotridge, was a pure Tlingit Indian and of course spoke the language perfectly.

Image Number: 85733

In those days there was considerable linguistic research in this Museum. In 1909 I enjoyed the invaluable experience of accompanying Edward Sapir, then a young instructor, to Utah, where he studied the language of the Northern Utes of the Uintah Reserve while I recorded folklore and archaeology. It was my first field trip. The following year, in the spring of 1910, Dr. Sapir made arrangements for Tony Tillohash, a Paiute Indian, to come from the Indian School then at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, to be informant in his seminar in American Indian languages. Of course Sapir did extra-mural work with Tony, and as a result later published his trilogy in the Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Vol. 65, Nos. 1, 2, 3, 1930 and 1931: “Southern Paiute, A Shoshonean Language,” “Texts of the Kaibab Paiutes and Uintah Utes,” and “Southern Paiute Dictionary.”

In the progress of this work, Sapir took more than two hundred songs from Tony Tillohash. In those days there were no electronic recorders, tape or wire, or even electrically driven dictaphones. One recorded on the wax cylinder of an Edison phonograph, winding up the spring by hand. The reproducer, used by the average person to play commercial music records, could be replaced by a recording attachment, which cut the wax surface of the cylinder as the informant sang or spoke into it. The recorder was then again replaced by the reproducer in order to hear the record.

These two hundred records are still in our possession, and have recently been renovated after years of neglect. Dr. Sapir’s father, a cantor, transcribed a few of them, and Sapir expected eventually to publish them, but his lamented death in 1939 at the age of only fifty-five put an end to this project, and the songs have not been utilized.

However, these two hundred wax cylinders are only about half the records of aboriginal song and speech in the Museum’s possession. Dr. Frank Speck, about this same time, 1910-1920, made many records of northeastern Algonkian languages: Penobscot, Malesit, Micmac, Passamaquoddy, and Montagnais, and also a large number of Yoruba records from a visiting member of that African tribe. Dr. Wilson D. Wallis, who was instructor here for a short time, made a number of records from a Hopi Indian of Arizona; Louis Shotridge gave Sapir a few songs and ceremonies in Tlingit, and various other records were taken. I think all were given by native visitors to the Museum, not by taking the machine into the field.

For years no study was made of any of these records, and of most of them no use has ever been made, but just recently the Penobscot and Malesit records have been sent to a young man in Maine, Mr. Nicholas N. Smith, who has been playing them to the Indians and getting them translated.

In addition to these, the Museum has received from time to time records of aboriginal song and speech on discs, tape, and wire, so that a small library is being built up, and the Museum is fulfilling its scientific obligation to save for the future everything possible of the life of other peoples.

At present I am the only person in the Museum engaged, whenever possible, in the study of unwritten languages, and I am specializing in one group, the Piman family of the Utaztecan stock. Among the other more variant members of this linguistic stock are the Aztec, Yaqui, Tarahumar, Ute, Paiute, Shoshone, Comanche, Hopi, and many others. The Piman family consists of six slightly differentiated languages for a thousand miles down the Mexican Sierra Madre from Arizona to Jalisco; from north to south they are the Pima, Papago, Névome or Lower Pima, Northern and Southern Tepehuán, and Tepecán. The last-named I first visited in 1911, and in 1917 published a very amateurish grammar on it. A somewhat better grammar, that on the Papago, was published as a Monograph of this Museum in 1950. I have visited the two Tepehuán groups, and the sole one still uninvestigated is the Névome. After obtaining data on the latter I hope to spend several years working out the comparative grammar of the group.