The first season of the collaborative Azerbaijani-American Lerik in Antiquity Archaeological Project (LAAP), co-directed by Ph.D. student Lara Fabian (Penn AAMW), recent graduate Dr. Susannah Fishman (Penn Anthropology), and Dr. Jeyhun Eminli (Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences), was funded by the Kolb Foundation, and supported by the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences.

Trekking to the top of a peak in the Talish Mountains in the southeast region of Azerbaijan, we take a moment to catch our breath and gaze out over the valley below, taking in the sweeping view…of fog. We can barely see our own team members, let alone the mountain passes we are trying to trace in order to understand how ancient people lived at the edge of the Achaemenid (550– 330 BCE), Seleucid (330–150 BCE), Roman (100 BCE–300 CE), and Parthian Empires (250 BCE–250 CE). In addition to these imperial powers, the nomadic and politically fragmentary Sarmatians wielded considerable influence concentrated nearby in the North Caucasus Mountains, and the local kingdoms of Iberia, Albania, Atropatene, Armenia, and Colchis managed to carve out space in the complicated political landscape of the South Caucasus. These mountains were both a physical boundary that empires had trouble conquering and a crossroads where diverse peoples met, traded, and traveled to get from one place to another. Empires depended on the mountains as a source of mercenaries and commerce. But archaeologists rarely work in highland zones, so we are just beginning to learn more about these dynamic communities.

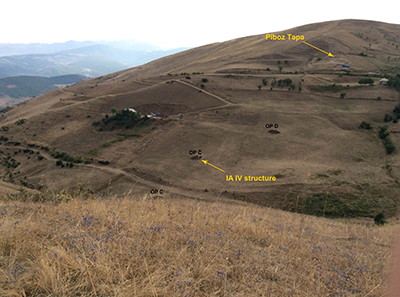

LAAP is an Azerbaijani-American collaborative expedition that seeks to understand these mountain dwellers between empires. Dr. Jeyhun Eminli, the project co director from the Azerbaijan National Academy of Science Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, has been excavating the necropolis Piboz Tepe since 2012. He has uncovered 133 remarkable burials— some with rich grave goods— and abundant Achaemenid-Parthian period tombs. This gives us a detailed snapshot of how people were treated in death, but we still do not know much about how they lived. With the collaborative work of LAAP, we are helping to contextualize the mortuary dataset through mapping and survey of the archaeological landscape, excavation of domestic contexts, ceramic technological analysis, zooarchaeology, and the scientific analysis of human remains.

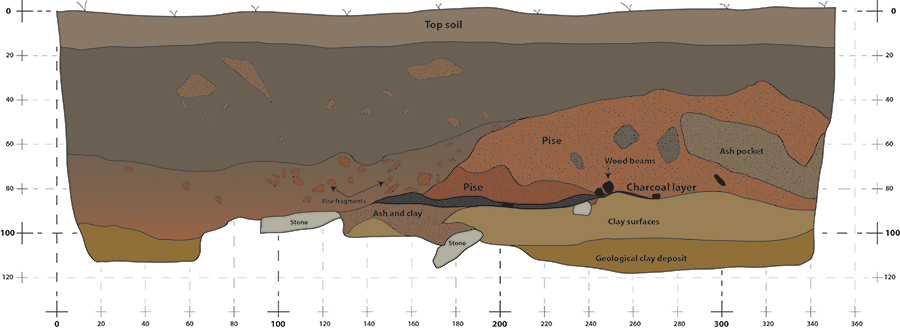

During the summer of 2016, work continued at the necropolis under the direction of Eminli and Emil Iskenderov, uncovering an additional 28 graves, which were studied by physical anthropologist Selin Nugent in order to understand more about the lives of the deceased. Fishman and Fabian excavated several test trenches below the eastern slope of Piboz Tepe in order to find evidence of the settlement that supported the necropolis. The most striking discovery from the test excavations was a burnt mud and wood beam domestic structure that was carbon dated to 440–350 BCE, or the Late Achaemenid period. This is the very first securely dated evidence for a non-urban settlement of this period in the region. We also carbon dated two burials, and found that they were from around the same time as the domestic structure, 370–220 BCE. However, while the necropolis has large amounts of imperial-style material culture (ceramics, weapons, jewelry, etc.), the domestic structure did not contain a single piece of evidence for imperial engagement. This suggests that people may have been making choices about how to use imperial culture in different contexts. However, we only excavated part of this house, and we must expand excavations to learn more about this structure and possibly others.

In addition to excavation, we conducted archaeological survey for an 18 km2 area of rough and varied terrain, mapping known sites and recording new ones. In order to facilitate quick data recording, we used a GPS-based system running on tablets and phones that allowed the real-time recording and sharing of survey results. This mapping and survey helps us understand how people lived in the landscape: where communities chose to live, where they placed their dead, and how these choices changed over time. It also allows us to collect geological samples of clays available in the region, which we use to study whether ceramics found in excavation were produced locally or imported from afar.

Without the modern technology that we used to conduct our survey, like GPS and satellite imagery, it would have been very difficult to traverse this rugged terrain without local assistance. And yet, we know that people and things were traveling across this area: we find imperial style ceramics, weapons, and jewelry, as well as descriptions of travel from Classical authors such as Strabo and Xenophon. These movements were dependent on local communities that enabled their passage. How did local communities decide what to let through, what to incorporate into their own cultural practices, and what to keep out? How were these local communities entangled with broader imperial networks? While the initial foggy view from the top of the mountains may have been limited, it is clear that more excavation, survey, and scientific analyses will help explain these complicated social negotiations.