![Adze collected by Sylvanus W. Godon during the cruise of the Potomac. The adze was first deposited with the American Philosophical Society in 1834, and transferred to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia in 1871. It eventually found its way to the University Museum's Pacific collection during the early 1930's. The original description, found in the records of the American Philosophical Society, is as follows: "Hatchet from the Society Islands, not in use at present—they were formerly used for all purposes, such as cutting trees, building their houses, etc., the twine is made of filling [sic] part of the Cocoanut, and is very strong—Some of these Hatchets are very large."](https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/files/1972/01/Adze-Potomac-Gordon-Collection.jpg)

Museum Object Number: 87-43-130

In February, 1831, an American merchant ship, the Friendship of Salem, anchored off the northwest coast of Sumatra, was attacked and plundered. When the captain, Charles M. Endicott, and several members of his crew went ashore to buy pepper, a Malayan boat seized the opportunity to pirate the ship. Within minutes, the Friendship vas overrun with natives who quickly gained control over the remaining crew. After killing the first officer and two seamen, and seriously wounding others, the Malays proceeded to remove everything of value aboard the ship. The total cache amounted to 12,000 dollars, 12 chests of opium, all the ship’s papers, spare sails, rigging, cabin furniture, chronometers, nautical instruments books, charts, and wearing apparel. Except for a small cargo of pepper, the marauders managed to strip the Friendship of everything that was not bolted to her decks. With the help of a few friendly natives and three American ships anchored in a nearby harbor, Captain Endicott managed to regain control of his ship before he pirates could run her aground. With the ship again under his control, Endicott could do little else than sail what remained of his command back to the United States as quickly as possible. Six months later, the captain succeeded in bringing his ravaged vessel home to rest in Salem, Massachusetts.

The sight of an empty ship anchored in one of he nation’s busiest ports aroused immediate interest and consternation. Within days, every newspaper in the country had published the story if the “Outrage against the Friendship.” Alerted D the news, Secretary of the Navy Levi Woodbury later Justice of the Supreme Court) launched an ‘mediate investigation. Meanwhile, three gentlemen from Salem called on President Andrew Jackson to demand punishment of the culprits responsible for the Friendship’s debacle. Acknowledging the request, Levi Woodbury emphasized that “every necessary preparation” was being undertaken to demand immediate redress.

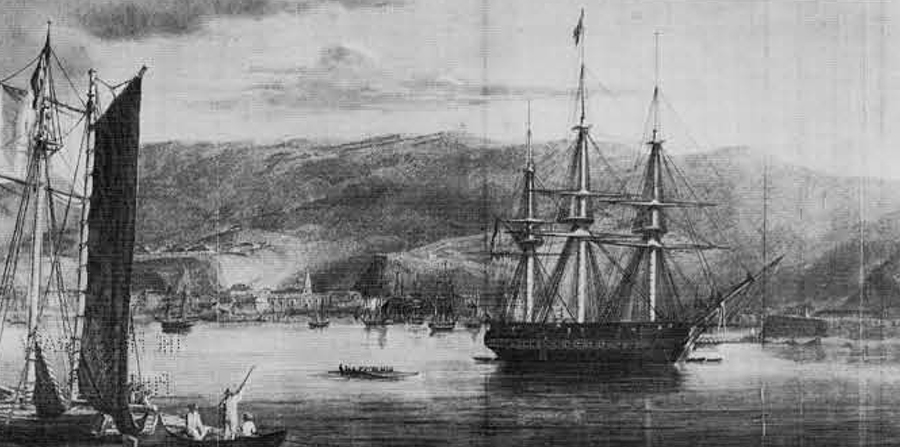

By a fortuitous coincidence, the U. S. Navy frigate Potomac, the nation’s newest and most advanced 44-gun man-o-war, was loaded and ready to sail for Europe on her maiden voyage, when the Friendship made its crippled appearance in Salem harbor. No less an honorable personage than Martin van Buren, President Jackson’s newly appointed ambassador to the Court of St. James, was scheduled to accompany the Potomac on her first cruise. After reaching England, the Potomac was to sail ’round Cape Horn and assume the duty as flagship of the Pacific Squadron stationed in Valparaiso, Chile. In the midst of final preparations for sailing, orders from Washington reached the frigate, changing her itinerary. Instructions from the Secretary of the Navy directed the captain of the Potomac to make “all haste for Quallah Battoo” along the north coast of the island of Sumatra.

On August 27, 1831, the Potomac, with orders to “vindicate our wrongs in that savage outrage,” embarked on her historic mission. One witness to the launching, a highly romantic reporter from Philadelphia’s National Gazette, noted that “with bellying sails swelled gently to the wind, the gathering force proudly bore [her] away, heaving up and dashing away the foamy billows from her bow.”

Commanding the expedition was Commodore John Downes, a veteran of the wars against Tripoli and the War of 1812. In 1815, while serving under Stephen Decatur during the “Algerian Crisis,” he captured an Algerian brig carrying 22 guns and 180 men. Before his recent promotion to Commodore of the Pacific Squadron, he had captained ships in both the Mediterranean and the Pacific. A highly competent officer, Downes’ past experience in both the martial and maritime arts would serve him well in his present assignment.

Sailing with the commodore was his ten-year-old son, John. It was common practice before the creation of the Naval Academy to train future officers directly aboard ships. Beginning as midshipmen, young boys would continue their naval training until deemed fit for promotion or released for incompetence. Since promotion to ensign never occurred before age twenty, a midshipman’s training for sea duty was long and thorough. To complete their education, a schoolmaster always sailed with the boys to instruct them in scholarship. The schoolmaster responsible for the education of the seventeen midshipmen aboard the Potomac was Francis Warriner. An aspiring author and man-of-letters, he succeeded in publishing his own account of the three-year cruise soon after the frigate reached home port. John, the commodore’s son, was to rise to the rank of commander before falling in the service of his country towards the close of the Civil War.

Another member of the cruise who had also begun his naval training at ten years of age, but had now risen to the rank of past-midshipman, was Sylvanus W. Godon. A native Philadelphian, he had been forced into the naval service as his only hope for an education after his impoverished father, a noted French mineralogist and member of the American Philosophical Society, became tragically insane. Godon eventually acquired the rank of rear admiral. After a long career, he retired in 1871 to live out the rest of his days at his ancestral home in Blois, France.

Other members of the Potomac’s crew included Nathaniel Oliver, private secretary to Downes and a long-time sufferer of consumption. As a last resort he had taken to the sea in the hope of making a recovery, but the disease was too advanced and he died halfway through the cruise. He was buried with full military honors.

Of the three surgeons assigned to oversee the health of the crew, one was Jonathan M. Foltz, a native of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. He had once walked all the way from this city to Washington, D. C., to personally plead with the President for assignment to a navy ship. This example of determination and initiative characterized his entire career, culminating in the promotion of Foltz to Surgeon General of the United States Navy.

The number of men sailing with the Potomac from New York in August, 1831, totalled 500. Of these, 40 were officers, and 44 were marines. The rest consisted of seamen, petty officers, landsmen, and boys. At least two members of the crew were black, but the exact percentage of integration is unknown. Nevertheless, at a time when slavery was the custom and the rule, the presence of even two free-blacks aboard the Potomac is noteworthy.

As the lighthouse gradually receded from view, the crew and officers set to the tasks at hand. Following the usual route pursued in those days for the Indian Ocean, the frigate sighted the Cape Verde Islands on September 21 and then shaped her course for the coast of Brazil. Three days later, a chance encounter with a supposed pirate ship provided the crew with an opportunity to relieve the monotony of their routine. Coming within two leagues of the Potomac, an unidentified ship suddenly turned about and sped away in the opposite direction. Calling the hands on deck, the captain ordered all canvas raised and immediately gave chase. The frigate made great strides towards overtaking the fleeing vessel, but nightfall and an approaching storm forced a halt to the race and the vessel was allowed to escape. One of the crew noted in his personal diary the disappointment of those aboard the Potomac: The stranger took his leave and left us to run out and secure our guns without the pleasure of such an adventure as we had anticipated.”

During this period, a concerted effort to suppress the slave trade was being carried out by American and British naval forces stationed off the coast of Africa. It was speculated that the vessel leading the Potomac on a merry chase had probably been engaged in this illicit traffic.

On the night of October 5, about one-half hour to midnight, the frigate crossed the equator, an event usually marked by riotous ceremony. But the late hour forced its cancellation, “very much to the satisfaction of the uninitiated and to the great disappointment of our old tars.” The frigate sighted Cape Frio on the afternoon of the fifteenth, and, the following day, put into the harbor of Rio de Janeiro for an uneventful two-week stopover. On November 3, the Potomac began her stretch for the Cape of Good Hope.

Not long after the Potomac sailed from New York, the members of the crew began organizing a “Company of Dramatists.” The highlight of their thespian efforts was to be an appearance before the king and queen of the Sandwich Islands midway through the voyage. Meanwhile, the first performance of the “Company” took place on the evening of November 22, when the frigate was well started on her run from Rio to Cape Town. A farce in two acts called “St. Patrick’s Day” was followed by an olio of songs, duets, and recitations. A member of the audience at this memorable event recalled that “the play with several of the songs excited much mirth and the entertainment of the evening received the praise they merited.”

The Potomac arrived at Cape Town on December 6, and was received with great excitement by the inhabitants. This was only the second American ship—after the 1828 visit of the U. S. frigate Vincennes—that the people had seen, and they eagerly overran the decks exploring, probing, and in all ways satisfying their curiosity. Since the crew was not allowed to leave the ship, the sight of the “young, the gay, and the beautiful” crowding on board brought mutual pleasure to all.

The Potomac left hospitable Cape Town, December 13, 1831. Five days later, she rounded the Cape of Good Hope and entered the Indian Ocean, running headlong into a violent storm. At the cry of “Reef topsails, reef!” every man ran to his station to hoist the sails and secure the decks. The scene was one of indescribable confusion: “The sea broke over us in every direction, deluging our main and spar decks, fore and aft, at every roll, in which the guns on our spar deck several times tasted the wave.” The storm terrified the new hands in its severity, but at least the ship was spared a visitation by the Flying Dutchman, although many eyes kept a sharp lookout, and many men half-believed she would soon appear. This superstition was universal among seafarers.

One diarist mentions that the tale was often told of the Flying Dutchman, who “continues to haunt the seas in the neighborhood of the Cape, always close-hauled to the wind and under heavy press of sail.” The storm raged for seven days and finally, on the 21st, began to abate.

Halfway between Cape Town and Australia, the ship sighted the islands of St. Paul and Amsterdam. As the frigate drew closer to the Sumatran shore, Captain Downes conducted a thorough inspection of the force destined to attack Quallah Battoo. With great singlemindedness, the men prepared themselves for combat:

The different divisions were formed and went through their evolutions better than could have been expected from men who detest the very name of soldier or marine and have so great an antipathy to that part of a ship’s company that they are ever ready to dub them with the most opprobrious epithets. But at this period, such feelings were buried and they joined with the guard with one voice and determination to revenge the death of their countrymen. They knew their duty and were determined at all hazards to perfect the mission on which they had been ordered.

On the 28th of January, the frigate passed Hog Island, lying off the coast of Sumatra. Unfavorable winds delayed the Potomac’s arrival off Quallah Battoo until February 5. The interim was used to disguise the ship in order to conceal her identity as a man-o-war from the natives. The guns were run in, the ports closed, and the sails were casually rigged to give the outward appearance of a merchantman. A Danish flag hoisted atop the mast completed the disguise.

The precautions taken to prevent discovery of the frigate’s real intentions were successful. The natives were deceived: the attack made against them the next morning was a complete surprise. At half-past two on the afternoon of February 6, one of the ship’s whaleboats, led by First Lieutenant Irvine Shubrick, advanced toward shore to reconnoitre the village and locate its forts. Two hours later, the small party returned without having landed, because of the “warlike appearance of the natives.” Preparations for a midnight attack against the village then began in earnest. Upon leaving Rio de Janeiro, the crew had been mustered and 260 men selected to “avenge the death of our countrymen.” Divisions were formed and drilled every day, so that by the time the Potomac reached Sumatra, the men were well-trained and eager to commence fighting. Significantly, on this day only three men had reported to sick bay. Since the daily “binnacle” list averaged twenty or more, this indicated a high degree of enthusiasm and unity of purpose.

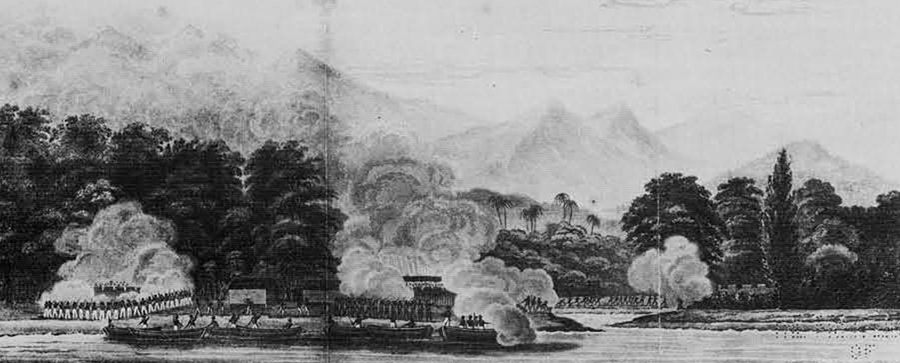

At midnight all hands were roused from sleep and called topside. Within minutes, the decks swarmed with officers, marines, and seamen busily arming themselves with weapons and issuing last minute instructions, “their bosoms .. . heaving with delight at the martial sounds that broke the stillness of the hour.” The morning star was just rising as the boats left the ship, silently rowing towards shore. One hour later, as the small flotilla came to within two miles of their destination, a meteor blazed across the sky, cheering the men who viewed the event as a sign of good fortune and a promise of victory. Upon landing, the men formed into four divisions flanked by a company of fusileers, and followed by six-pound “Betsy Baker” cannons. Quietly marching off, they headed for the lower fort where the second division separated from the group and disappeared into the jungle. Within minutes, “the din of a hundred firearms” marked the beginning of battle.

The marine guard with the first division of musketeers and pikemen proceeded to the center fort, which was taken after a short but bloody engagement. One marine was killed and others were slightly wounded, but “all who had a semblance of a native” were slaughtered. The remaining force of 85 men, led by Shubrick and Lieutenant Pinkham, carried the “Betsy Bakers” over to the third and most formidable fort. Enemy fire greeted their approach, quickly answered with a volley of lead that “shook the high arch of heaven with its thunder.” Charging from the rear, the Americans fought to make a breach in the fort’s defenses, assisted by the fusileers who stationed themselves on the opposite side to create a crossfire. One of the “Betsy Bakers” was taken to the bank of a creek and used for cannonading the enemy schooners and boats lying in the water. “Sweeping their decks fore and aft,” a great many natives were killed, and considerable damage wreaked on their vessels.

In the second charge against the main fort, one marine was shot in the head, expiring instantly. His comrades retaliated by “heaping the heathen pile upon pile at every discharge and staining the green sward with the blood of the victories of our ungovernable fury.” For all their fury, the fort still remained in the hands of the Malay warriors at the end of the second charge. Finally, ten bags containing forty musket balls each were discharged in three successive volleys. phis succeeded in dislodging the enemy from heir stronghold. The force of the charges, how-ever, shattered the gun carriage and destroyed it or any further use. Seconds after the last charge lad been made, the fort blew up, trapping its lefenders as they rushed to escape. With an ;exultant shout, past-midshipman Godon clambered to the top of the rubble and planted the American flag. The victory was now complete.

The battle of Quallah Battoo had lasted less han seven hours. In the melee, two Americans were killed and seven injured. Enemy casualties were estimated at more than one hundred killed and twice that wounded.

At the sounding of the bugle, the victorious pand collected in the boats and headed back to he ship, where they were greeted with cheers and usty shouts. While the two slain heroes were pbeing prepared for sailors’ burial, their fellow warriors regaled the others on board with detailed accounts of their own prowess in battle. All agreed that the enemy had been a worthy adversary: “They would not yield while a drop of their savage blood warmed their bosoms or they had strength to wield a weapon—fighting with that undaunted firmness which is characteristic of bold and undaunted spirits.”

The following morning, the ship anchored a mile offshore, bombarding the village and its remaining forts with a steady barrage until one o’clock in the afternoon. That evening three natives, bearing a flag of truce, pulled a boat alongside the frigate. They were conducted on board and presented to the commodore. After listening to their entreaty to cease hostilities, Downes offered them assurances of peace, but sternly warned that “if forbearance should not be exercised … from committing piracies and murders upon American citizens, other ships of war would be despatched to inflict upon them further Punishment.”

On the morning of the 5th, the ship was visited by Po Adam, a friendly rajah, who had been instrumental in facilitating the escape of captain Endicott and the recapture of his ship. He was warmly embraced by Mr. John Berry, second mate on the Potomac, who had met Adam the year before as a crew member of the Friendship. During the day, friendly Malays from nearby tillages kept a steady flow of gifts coming to the ship—great quantities of fruits, vegetables and poultry.

February 9 brought an event of special mportance to the crew of the Potomac. After 166 Jays at sea, the men received their first letters from home. A passing American brig, Oliver, 113 Jays from Boston, dropped off a packet in the morning. Not until the frigate passed another American ship, the Philip, bound for Philadelphia, over four weeks later, could the men send back their replies.

By February 15, the Potomac had replenished her stock of wood, fresh provisions, and water. Three days later, she sailed from Quallah Battoo ‘or Batavia. On the fourth day out, February 22, Captain Downes perpetrated a little joke on the crew. It was the hundredth anniversary of the birth of George Washington and word had been passed that an “extra-extra” allowance of grog would be served at noon. After a salute of seventeen guns had been fired, Downes mustered the crew and, after solemnly admonishing them not to drink a quantity sufficient to intoxicate,” announced that an extra quantity of water would be served with the usual allowance of grog. As evidenced by the grumbling that followed this announcement, the only one who could be said to have appreciated Downes’ “little joke” was Downes himself.

Passing through the Straits of Sunda, the frigate, on March 6, resupplied her stock of wood and water at Bantam, and on the 19th anchored off Batavia, remaining until April 8. During her stay, the sick list swelled with men who were stricken with dysentery. Several died. The commodore’s small son was also stricken—with fever. For days, he wavered between life and death, but slowly his health improved and by the time the frigate reached Chile, several months later, he had completely recovered. The death of Oliver, the commodore’s private secretary, occurred soon after the frigate put to sea from Batavia. A letter found among his effects revealed profound despair at the hopelessness of his situation, compounded with the knowledge that he would never see his family again:

My disease in the throat is in a dangerous state; I begin to fear for the consequences. . . . One thing, however, makes me happy. It is the birthday of my little Billy. God bless my poor Willyl[sic]. When shall I see him again! Far, far away is he—and I, all alone on the ocean billow, yes—all alone, though surrounded by half a thousand.

Oliver’s death saddened the entire crew. To express their sympathy, they passed a hat to collect contributions for his widow and children.

The Potomac entered the China Sea by way of the Gaspar Straits, arriving at Macao on June 5. After a stay of only one day, she continued on her voyage across the Pacific, stopping at Honolulu in the Sandwich Islands on July 23.

For the first time since the frigate sailed from New York, almost a year before, the crew received permission to go ashore. For two days the men feverishly burnished, polished and scrubbed the ship in preparation for the big moment. At last, the morning of July 25, the men were dismissed. Pandemonium immediately followed as every man rushed below, to hastily throw together small bundles of clothes and goods for barter, and then rushed back topside, to fly down the gangplank to shore. The next twenty-four hours they: “managed to dispose of their bundles at half cost, got most gloriously intoxicated, fought, acted the tar, returned on board with most awfully scarred features, got partially sober, and returned to their duty—much the worse for the ‘cruise’ in pocket, appearance, and feelings.”

The king and queen of the Sandwich Islands visited the ship in August, thus honoring the Potomac with its first royal recognition. Five days later, the “Company of Dramatists” presented the royal audience with a well-rehearsed performance of two plays. a comedy and a tragedy, plus the familiar olio of songs and sketches. Their efforts received enthusiastic applause. For a reward, the actors were granted a day’s liberty. “Their bacchanalian scenes . . formed a subject of amusement for many days.”

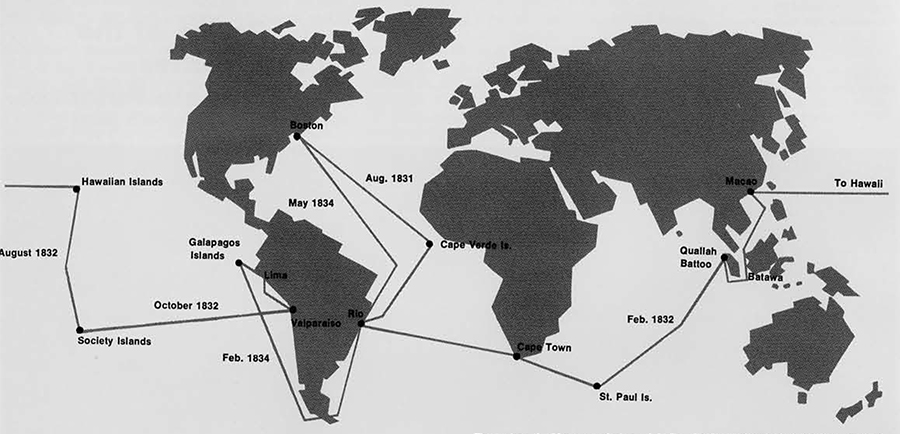

Leaving Honolulu on August 16, 1832, the Potomac made one last stop at Tahiti, in the Society Islands, before joining up with the Pacific Squadron at Valparaiso, October 23. For fourteen months she cruised the coast of South America, visiting United States’ consular ports and protecting American trade. In addition, Downes, as commodore of the fleet, executed his responsibilities to the seventy-one ships and 11,000 men serving under his command as members of the American naval force in the Pacific.

At last, on February 9, 1834, the Potomac embarked on her homeward voyage. The ship had, some months previously, been completely overhauled and painted, readying her for the long-anticipated great day. After a parting salute exchanged with the Chilian flag on shore, “the hardy tars heaved up the heavy anchors to her bows.” Passing through the Straits of Magellan, the frigate touched once again at Rio de Janeiro before turning north to the United States. Finally, after a voyage of two years and nine months, in which time she had logged more than 61,000 miles, and in the process had made a circumnavigation of the globe, the Potomac came home to rest in Boston Harbor, May 23, 1834.

Navy Department, August 9th, 1831

Sir,

Circumstances have occurred since the last instructions to you, which require a change in your route to the Pacific, and which may impose on you some new duties of a character highly delicate and important. A most wanton outrage was committed on the lives and property of certain American citizens at Quallah Battoo, a place on the western side of the Island of Sumatra, on the 7th of February last; the particulars of which are contained in the documents annexed, marked A and B.

You are therefore directed to repair at once to Sumatra, by the way of the Cape of Good Hope, touching on the voyage thither only at such places as the convenience and necessities of your vessel may render proper. On your arrival at Quallah Battoo, you will obtain from the intelligent shipmasters, supercargoes, and others, engaged in the American trade in that neighbourhood, such information as they possess in respect to the nature of the government there, the piratical character of the population, and the flagrant circumstances of the injury before mentioned, Should that information substantially correspond with what is given to you in the documents marked A and B, the President of the United States. in order that prompt redress may be obtained for these wrongs, or the guilty perpetrators made to feel that the flag of the Union is not to be insulted with impunity, directs that you proceed to demand of the rajah, or other authorities at Quallah Battoo, restitution of the property plundered, or indemnity therefor, as well as for the injury done to the vessel; satisfaction for any other depredations committed there on our commerce, and the immediate punishment of those concerned in the murder of the American citizens. Charles Knight, chief officer, and John Davis and George Chester, seamen. of the ship Friendship.

If a compliance of this demand be delayed beyond a reasonable time, you are authorized. in the following manner, to vindicate our wrongs—Firstly, having taken precautions, while making the demand. to cut off all opportunity of escape, from the individuals either concerned in that savage outrage, or protecting the offenders, or participating in the plunder, you will proceed to seize the actual murderers, if they are known, and send them hither for trial as pirates by the first convenient opportunity; to retake such part of the stolen property as can there be found and identified; to destroy the boats and vessels of any kind engaged in the piracy, and the forts and dwellings near the scene of aggression, used for shelter or defence; and to give public information to the population there collected, that if full restitution is not speedily made, and forbearance exercised hereafter from like piracies and murders upon American citizens, other ships-of-war will soon be despatched thither to inflict more ample punishment.

Any property restored, or indemnity given, you will deliver to the owners of the ship Friendship, or their agents, taking receipts therefor. Should the information obtained on the spot give a different character to the transaction from that furnished by the department. marked A and B, showing any real disapprobation of the plunder and murder by the population at large or by their rulers. or any provocation given on the part of our citizens. or the existence of a regular responsible government, acting on principles recognised by civilized nations in their conduct towards strangers, you will confine your operations to a regular demand for satisfaction on the existing authorities at Quallah Battoo….

With much consideration, your obedient servant,

Levi Woodbury