Museum Object Number: 29-69-2

As early as 1924 the art historian Ananda K. Coomaraswamy recognized the importance of the Penn Museum’s Brahmā sculpture, now on display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Dating to central peninsular India’s Later Cālukyan period (10th–12th centuries CE), it is known primarily for the inscription on its base identifying its maker and noting his connection to the Mallikārjuna temple (built by his architect father) at Kuruvatti in the modern state of Karnataka. Since the sculpture’s early publication, scholars have presumed it was created for this temple. But was this the case?

Approximately 170 cm tall, 77 cm wide, and 25 cm thick, the Brahmā is carved from a single slab of dark green chloritic or magnesian schist. Such fine-grained, soft metamorphic stones became the medium of choice of Karnataka’s artisans from the 11th to the 14th centuries, driving an aesthetic revolution in both sculpture and architecture. Brahmā and two diminutive flanking attendants—the goddesses Sārasvatī and Savitrī—stand on a base with two projecting faces, the central one of which bears the prominent inscription. An elaborate ornamental archway, or prabhāvali, springs from columns behind the attendants and encircles the principal figure. Although generally quite well-preserved, the sculpture has lost major portions of three of Brahmā’s four arms and several of the more delicate elements ornamenting the central figure and its surround.

Kuruvatti

The Brahmā is perfectly suited stylistically to the temple mentioned in its inscription, the Mallikārjuna at Kuruvatti. Actually fitting the image— physically and ritually—into this temple, however, proves nearly impossible. Unlike the collection of disparate images currently found in the temple’s common spaces, the Brahmā would have held a place of ritual distinction if it had been created for this temple. But it is much too large to fit in one of the temple’s exterior niches or in the three cells (which are vertically partitioned by stone shelves) that radiate off the sanctum, or garbhagṛha. The only place where the Brahmā could have been accommodated is in the sanctum proper, where the large Śiva linga and its pedestal currently stand. This possibility also has its own problems.

While temples do undergo shifts in cultic affiliation, temples dedicated solely to Brahmā are extremely rare. In virtually every known instance before the modern period, Brahmā worship within temple sancta involved a triad of images: Siva, Viṣṇu, and Brahmā. But placing three images the size of the Brahmā side by side in the Mallikārjuna’s square sanctum would render the space impossibly cramped. Rather than trying to force the Brahmā to fit into this sanctum simply because this temple is mentioned in its inscription, I wondered if it might not have come from a nearby temple designed to accommodate such a set.

Kalakēri

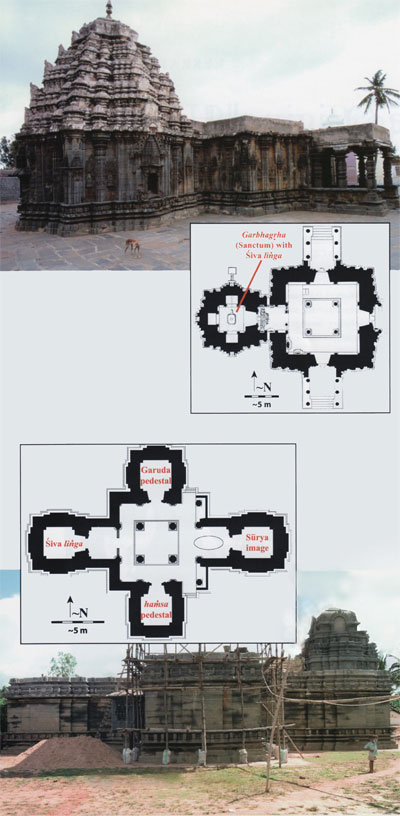

(Bottom) Basavēśvara temple and plan, Kalakēri.

happens that a letter in the Museum Archives identifies just such a temple. Writing to Museum Director George Byron Gordon in 1922, the Brahmā’s seller, Hagop Kevorkian, reports that the sculpture was removed in 1835 from “the temple at Kalkerry at Talook Kode, southern Mahratta County, India.” The modern village of Kalakēri, 48 km west of Kuruvatti, has two 11th-century temples. The quadruple shrine Basavēśvara temple there is the one I believe was the Brahmā’s original home.

The current disposition of images in the Kalakēri temple’s sancta indicates the disruption of an earlier arrangement. In the north and south chambers, crudely carved Sūrya and Nāga-nāgini images stand atop comparatively elegant, and much larger, pedestals. These images are mismatched to their pedestals physically, stylistically, and iconographically. The pedestals bear central images of Viṣṇu’s vehicle, Garuda, in the northern sanctum and Brahmā’s vehicle, the haṁsa (goose), in the southern one. In the western sanctum is a Śiva linga, while the occupant of the fourth, or eastern sanctum, ties the evidence together. Here stands an extremely fine image of Sūrya that is a perfect match, both to its pedestal bearing the sun god’s seven horses and, more importantly, to the Museum’s Brahmā!

The Sūrya and the Brahmā are essentially the same size with strikingly similar proportions, poses, and renderings of their figures. Their personal ornaments are nearly identical, as are many individual motifs used throughout the two sculptures. A particularly telling correspondence is the complex structure of their framing columns. Even the damaged inscription on the Sūrya’s base is strikingly like that on the Brahma’s in both orthography and content. Given Kevorkian’s identification of the site; the physical, stylistic, and epigraphic similarities between these two sculptures; and the tradition of housing sets of deities in multiple-shrine temples, it is almost certain that the Museum’s Brahma was removed from the haṁsa pedestal in this temple’s southern sanctum.

But where is the missing Viṣṇu for the Garuda pedestal in the northern sanctum? A well-known image of Keśava (Viṣṇu) in New York might be it. Purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art from Kevorkian in 1918—the same year he lent the Brahmā to the Penn Museum—this image is not as close a stylistic match. Its inscription, however, associates its maker with the artists of the other two images, and another letter to the Museum Director indicates that the Brahmā and the Keśava were brought from India together.

The case of the Museum’s Brahmā reminds us that the task of re-contextualizing museum art objects requires a broad spectrum of approaches. Stylistic evidence can reveal a great deal about an object’s probable provenience, as well as about the history of technological development and how it may have affected production and perception. Epigraphic evidence can also help us reconstruct elements of an object’s past and shed light on individual and group authorship and identity. But often the stylistic and epigraphic evidence alone cannot reveal the full story. Sometimes there is just no substitute for returning to the field with a tip from the archive, a map, and a measuring tape.

Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. History of Indian and Indonesian Art. London: Edward Goldston, 1927.

Dhaky, M. A., ed. Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture: South India, Upper Dravidadesa, Later Phase, A.D. 973–1326. 2 vols. New Delhi: American Institute for Indian Studies, 1996.

Newman, Richard. The Stone Sculpture of India: A Study of the Materials Used by Indian Sculptors from ca. 2nd century B.C. to the 16th century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, 1984.

Seshadri, M. “Sculptors and Architects of Ancient and Medieval Karnataka.” Journal of the Mysore University. New Series, Section A–Arts 29-30 (1970–71):1-10.