I

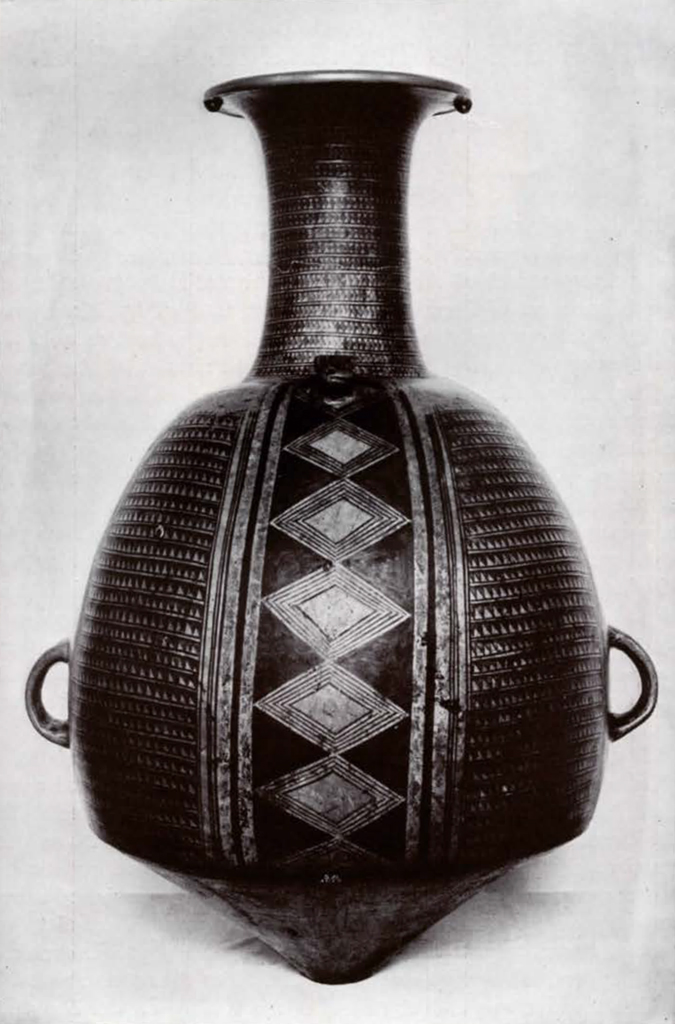

A Peruvian Aryballus

By gift of Mr. F. C. Durant the Museum has acquired an excellent and unusually large Peruvian aryballus, the most typical pottery vessel of the Inca period immediately preceding the Spanish conquest of Peru. It was secured in Peru by Mr. Durant in 1886. Seldom are these large vessels found intact, most of the known examples having lost their necks and rims. In the case of the Durant aryballus, the upper part of the neck and the rim were missing and the appearance of the break indicated that the damage had occurred in ancient days and the vessel retained in service, unmended. However, the lower half of the neck being intact, it was possible to restore neck and rim by comparing and copying those of the few large and the many smaller complete known examples.

Museum Object Number: SA4615

Image Number: 20439

As restored, the Durant aryballus stands forty inches high, one of the largest of its type. Indeed, only one larger example is known, with a height of approximately forty eight inches. According to Bingham, aryballi of ninety centimeters height—practically three feet—were not at all uncommon at Machu Picchu, the Inca city excavated by him, and this is approximately the height of several such figured in publications of European museums.

The forty inches of height is divided into an inverted conical base of seven inches, a body of twenty inches and a neck and rim of thirteen inches, the upper eight inches of which are restored. The body therefore occupies exactly half of the total height, the neck approximately one third and the base one sixth, the proportions being those which produce a vessel of considerable artistic beauty. The width of the rim is twelve inches, approximately equal to the height of the neck, and the greatest width of the vessel, exclusive of the handles, is twenty four inches, just twice that of the rim.

The massive vertical loop handles are set low on the body and a large knob, in the shape of a conventionalized animal’s head, probably a llama’s, occupies a prominent place on the front of the vessel near the base of the neck. These elements are constant features of the Peruvian aryballus, a standard type admitting of slight variation. The tiny nodes under the rim are also constant features, invariably on the same side as the handles.

The painted decoration is very typical of the Inca period, the range of variation in design being very slight and limited to a few characteristic motives. The colour scheme is equally simple, buff, red and black, the former two being employed mainly for backgrounds or slips.

The aryballus, so named because of its superficial resemblance to a type of Grecian vessel of sack shape, is found wherever the Incas penetrated. Conversely, it is never found beyond the field of their conquests, except for occasional pieces carried afar in trade, or rude imitations made by surrounding peoples.

The aryballus was doubtless used as a container for liquids, though the great variation in size, from five inches to four feet in height, indicates a corresponding diversity of use. Thus the smaller ones were probably employed as phials for precious fluids or as mortuary offerings in sepulchers, and the very largest, too heavy for ready transportation, probably stood in temples as receptacles for water or the native beer, chicha. Accurate representations of the use of aryballi of moderate size are found in the form of certain effigy jars. The vessel was carried high on the back, the angle of the body apparently fitting into the neck of the porter. A band or strap passed across the shoulders and chest of the porter, through the vertical handles and up over the animal knob at the base of the neck, this latter artifice preventing the topheavy vessel from upsetting. The form of the vessel is well suited to this purpose and there can be little doubt that its primary purpose was for the conveying of water in this manner. The ease with which water could be poured out of the vessel into a cup in the hands of the porter without putting down the ponderous urn is obvious. The orifices in the small nodes at the neck undoubtedly served to tie on the cover which protected the liquid from contamination.

II

An Unusual Stone Vessel

Another Inca Peruvian object of great interest and beauty has been lent by Mr. Durant to the Museum. This is a massive bowl of heavy hard black stone, the surface profusely decorated with coiling and wriggling serpents in half inch relief. These are quite symmetrical and equilateral. Fourteen snakes compose the decoration, one coiled in the center of each side and three wriggling to either side of these.

The purpose to which such an object was put must remain largely conjectural. Not many specimens of this type are known, and most of these are distinctly smaller and plainer. Only one similar bowl is known to the writer, one almost exactly similar except that it is apparently larger in size, illustrated by Joyce in his “South American Archaeology.” It is there termed a “stone mortar carved in the Cuzco style.” That it served as a mortar is, to say the least, doubtful and it is far more probable that it stood in an ancient Inca temple to hold or receive offerings or perform some kindred ceremonial and religious function.

Museum Object Number: SA4681

Image Number: 20476

III

A Puma Stone Cup

One of the most interesting and altogether puzzling artistic objects secured by the Museum recently is a small but massive and heavy stone figure of a feline animal, probably a puma, bearing on its back and sunk into the body a deep conical cup, all carved out of a solid piece of heavy hard black stone taking a good polish, practically identical with that used for the stone serpent bowl.

The stone puma has a maximum length of 13 inches, a width of 5 inches and a height of 7 ¼ inches. The rim of the cup has an outside diameter of 5 inches and an inside diameter of 4 inches, the walls being therefore a half inch in thickness. The cup is 3½ inches deep, the sides straight and converging towards the flat bottom, which is 2¾ inches wide.

Of massive proportions, highly conventionalized and symmetrical, perfectly finished, the surface covered with various decorative motives in low relief or incision, the specimen makes a most attractive and interesting figure.

The body is ponderous and the legs short, thick and mainly revealed in relief against the body, below which they extend for only one inch. The feet are shown as rectangular blocks with broad, flat bases. The tail also is shorter and more massive and the head much larger and more massive than is natural, but typically catlike with sub-semicircular ears, deep depressed oval orbits which may originally have been inlaid with eyes of another material, the mouth broad and conventionalized with the canine teeth prominent, slightly curving and projecting beyond one another.

The entire surface with the exception of the plain sides of the cup which projects above the level of the back is covered with carved designs and decorative motives in low relief or incised lines.

Museum Object Number: SA4627

Image Number: 20478

In the center of each flank is seen the principal decorative element, carved in low relief. Imagination may discern head, eye and tail but no vestige of limbs, and interpret it as a fish, worm or snake. Another large curvilinear figure, more enigmatic but less ornate, is seen over each rump. A large rectangular Helvetian cross is delineated on each thigh and others distributed on the body, including a string of eight around the neck, making a total of fourteen crosses. Of somewhat similar nature are three pairs of curvilinear, four-petaled rosettes found on the forelegs, cheeks and forehead. Various other small symbols and motives are carved on the borders of the body.

The massive tail is divided into segments by means of encircling incised lines, frequently of a chevron shape, and the outer and upper side of the tip is decorated with parallel short incised lines and one concentric circle. At the base of the tail on the upper side is carved a single sigmoid or figure 8 element through which a small depression has been drilled. There is a similar hole in the forehead. It seems most probable that small sticks on which banners were hung were placed in these holes.

From each eye depend two short objects in low relief, on each of which are two larger buttons. These may be interpreted as being of an illustrative rather than of a purely decorative nature, and may tentatively be termed tears.

These and other decorative or symbolic elements, nearly covering the surface of the figure, present an interesting question. In how far are they conventionalized representations of the actual or fancied markings and teatimes of the animal, in how far are they purely decorative and irrelevant, and to what degree are they esoteric symbols in some ceremonial way connected with the worship or religion of which the puma may have been a principal factor? It must be confessed that the archaeology and religion of ancient Peru are too little known to give an answer to these questions. Probably certain of the decorative ornaments would fall into each of the three classes.

Museum Object Number: SA4627

Image Number: 20479

As is so often the case, the puma figure came to the Museum with no record as to its provenience. This adds to its problem. Typical pieces can be assigned their places with considerable assurance, but unusual specimens such as this are often difficult to locate.

The stone puma apparently belongs to one of the ancient cultures of the highlands of Peru or of the adjacent portions of the surrounding countries, and probably to the oldest of the high cultures of that region, that known as Tiahuanacan, from the name of its ancient center on the shores of Lake Titicaca on the border of Peru and Bolivia.

The puma is the characteristic animal of Tiahuanacan art, and is found carved in stone, moulded in pottery and woven in cloth. The two latter forms are the more common, stone pumas being very rare. Puma heads are frequently attached to pottery vessels; these are generally somewhat conventionalized, with the faces upturned like the present specimen, but are normally plain and lack the ornate decoration, which makes comparison more difficult.

The concept of a figure, human or animal, with a depression in the upper side which forms a bowl or cup, is one which must have occurred independently to artists in many places and times. It is found, I am told, in the Orient, and occurs in several widely separated regions in America. In the National Museum in Mexico City is a great and beautiful figure of a jaguar or ocelot, another member of the cat family, with a deep and wide round cavity in the back. It is, however, reclining, naturalistic and unornamented, differing in everything except general concept from the present specimen. Such objects were known in ancient Mexico as quauhxicalli and stood in temples on or near the altars to receive and contain the hearts of the sacrificed victims. Another very similar form of figure in Mexico was that of which the well known statue generally termed Chac Mool is the type. This consists of a recumbent human figure in whose abdomen is a cavity for the reception of offerings. These are generally interpreted as gods of octli or pulque, the native drink of Mexico. This latter type, however, has even less in common with the stone puma now before us.

Museum Object Number: SA4627

The puma is thus a characteristically Tiahuanacan artistic and esoteric animal, and the shape of the bowl or cup is also Tiahuanacan, although the general concept of the figure is one occurring in many places in America and elsewhere. Furthermore, the general scheme of decoration, a lavish covering of the object with extremely conventionalized design elements, is characteristic of Tiahuanacan art.

As regards the design elements themselves, there is not one that can be called typically and solely Tiahuanacan. Several, however, are very characteristic of the general Andean region. The Helvetian cross, while apparently not a common Tiahuanacan element, is found constantly in the art of the Diaguite region of northwestern Argentina, which was an offshoot of the Tiahuanacan, and is not infrequent in the art of the Incas, in many respects the lineal descendants of the Tiahuanacans. The same may be said of the rosettes. On the other hand, these two elements are practically unknown in Mexico and Central America; they are peculiarly Peruvian.

The “tears” descending from the eyes are another characteristic which links the figure to the Tiahuanacan culture. The Weeping God was the primary deity at this great culture center, occupying the central position in the great monolithic gateway which is one of the great accomplishments of aboriginal America. The weeping eyes are also commonly found on the great burial urns of the Diaguite-Calchaqui region of northwestern Argentina, a culture closely connected with Tiahuanaco.

As regards the scrolls, sigmoid motives and smaller decorative elements, they appear to find their closest counterparts in the art of Chavin de Huantar, a culture center in the lower highlands of Peru. The art of this culture is still imperfectly known but seems to represent a blend of, or a mean between, the art of Tiahuanaco and that of the southern coast.

As the result of our careful examination of the stone puma, therefore, we determine that, if not of pure Tiahuanacan origin, at any rate it was produced by a culture closely related to and profoundly affected by that of Tiahuanaco.

IV

Extraordinary Peruvian Gold Vases

Another important accession to the Peruvian collections was made last year in the form of two unusually large and excellent gold effigy vases. These were carried from Peru to London in 1888, according to our informant, and from there secured by purchase.

Effigy vases of this type are among the most typical objects from the northwestern coast of Peru and are considered characteristic of the Chimu culture which flourished there in pre-Inca days. Most of those known, however, are of silver, gold vases being comparatively rare.

Museum Object Numbers: SA4642 / SA4643

Image Number: 20342-20344

These two vases are of approximately equal height but of different widths. Both are made of thin and apparently pure sheet gold, that of the smaller specimen being slightly heavier. Technically, they are admirable and puzzling productions, inasmuch as each seems to have been hammered out of one single piece or sheet of gold, being without seams. The difficulty of such an operation can hardly he realized by the novice. The features, and possibly the entire vessel, were beaten into shape and proper thinness over a form of stone or wood. The smaller vessel, it is true, is pieced, though even this is done in a remarkable manner. The main part of the tube ends just above the forehead of the face, where it is hammered out into a thin tenuous edge. Another tube of equal width and proper length was prepared, also apparently hammered out of a solid piece of gold without seams. The lower end of this was then slipped over the upper end of the main tube for a distance of about five sixteenths of an inch and the whole then hammered together, apparently without soldering or welding. On the exterior the hammering has been done so as to make a firm juncture, but on the inside the sharp ends of the lower tube have not been joined to the main vessel and project beyond the surface. The upper rims are thicker at the edge than the walls throughout the vessels, but it is uncertain whether the metal here is solid or whether the thin sheet is bent over upon itself and hammered down, leaving an interior cavity.

The height of the larger specimen is 12¾ inches and the weight is slightly more than 13¼ ounces. The other specimen measures 12½ inches in height and weighs nearly 14 ounces.

The region of the Gran Chimu, on the northwest coast of Peru near the present city of Trujillo, from which these gold vessels probably came, was one of the great culture centers of ancient Peru. Commencing in the hot and, when well irrigated, very fertile valleys, in early times, the inhabitants had achieved a very high grade of civilization, as manifested in their architecture, pottery, textiles, woodcarving, metalwork and other products long before the forces of the all conquering Incas from the highlands of Peru near Cuzco, about the year 1400, added the Chimu Kingdom to the great Inca Empire and to some extent imposed Inca culture upon its people.

The quantity of the gold objects made by the ancient Peruvians is almost incredible. The fabulous treasures of Atahuallpa are not within the scope of this present article, but in this same Chimu region traditions of immense treasure in buried gold have ever incited the lust of adventurers. Tradition has it that upon the coming of the Spaniards, the news of their gold fever having preceded them, two enormous treasures in gold objects were buried, known ever since as the “Great Fish” and the “Little Fish,” peje grande and peje chico. Shortly after the conquest a renegade chief, Cacique Tello, confided the secret of the peje chico to Don Garcia Gutierrez de Toledo, who at once made use of his information to such good effect that the “Royal Fifth” claimed by the crown amounted in value to $1,250,000. As a result most of the inhabitants of Trujillo have spent the last four hundred years searching for the peje grande.

The two wonderful gold cups now in the Museum are the largest of their kind known. Larger cups of silver are known—the Museum itself possesses one much larger, but I am unable to find any record of gold vases so large. The one illustrated by Lehmann in ” The Art of Old Peru,” which comes from Ica, much further to the south, whither it must have been taken in trade, is hardly more than half as high.

V

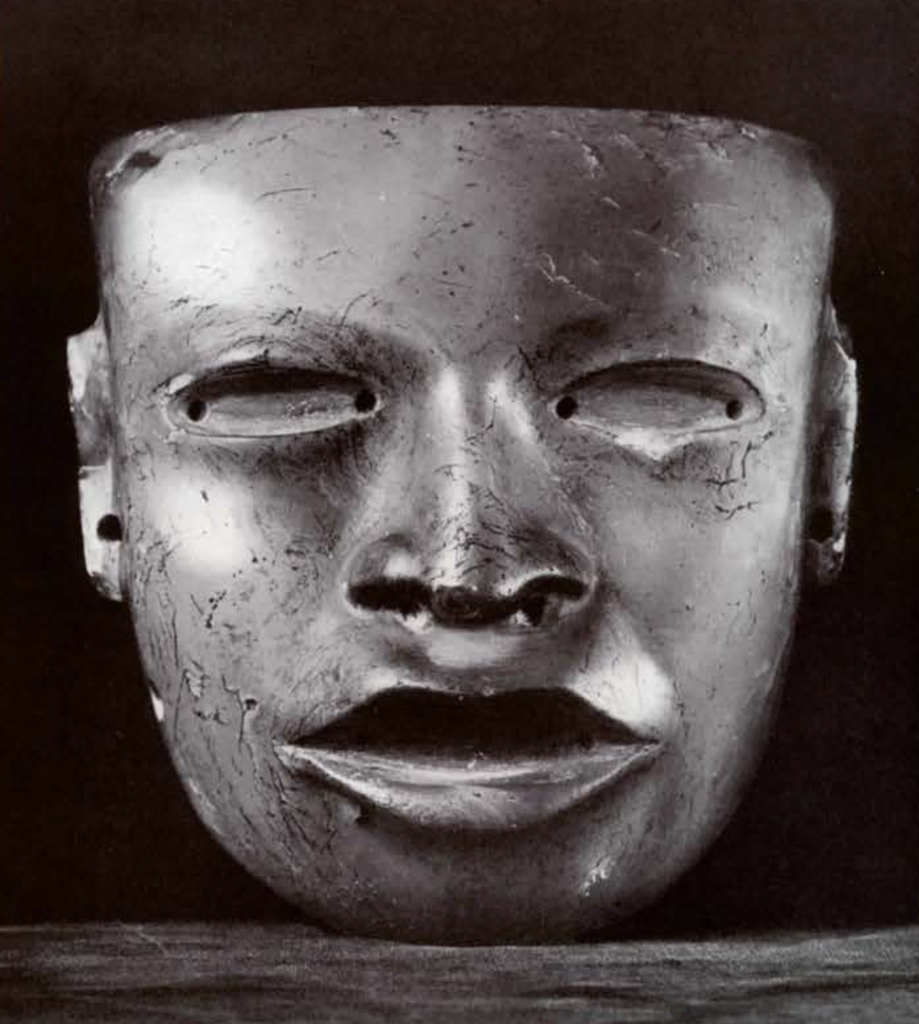

Two Mexican Stone Masks

The Mexican collections of the -Museum have recently been enriched by the acquisition of two stone masks formerly in the John Quinn Collection. Both of these are exceptional pieces, among the finest of their kind, although stone masks are by no means rare objects in large collections of Mexican archaeology. Most of them, however, are either small or of indifferent and rude workmanship and pieces of real excellence are rare.

Museum Object Number: NA10799

Image Number: 20007-20009

The smaller mask is a beautiful specimen of translucent apple green marble, resembling jade in its translucency and high polish. Its height is approximately equal to its width, about six inches, and the maximum thickness, from back to tip of nose, is just half of that. The face is, therefore, slightly more flat than natural, the nose somewhat less prominent, and the forehead flatter.

The back of the mask is concave. The ears are shown in a conventionalized fashion, narrow and rectangular, but on the other hand, the facial features are remarkably and unusually well carved. The eye orbits are deeply hollowed out, the lids being outcurved in very naturalistic fashion. The corners of the eyes contain shallow drill holes; these may be traces of the process of carving—it is known that in the later period of Mexican art much carving was done, especially in the softer stones, by drilling shafts with a hollow drill and breaking away the cores and the walls—but it is more probable that they were intended to aid in holding the inset eyes with which the finer masks frequently were provided, but which in most cases have disappeared with the passage of time. These eyes were generally of bone or shell with the irises painted black, or even with hemispherical irises of iron pyrites inserted in eyeballs of bone. The supraorbital ridges, the cheeks and the chin are all very well depicted. Though the nose is somewhat flat, the wings are well portrayed and drilled cavities simulate the nostrils excellently. The mouth, too, is admirably done with protruding lips of natural shape and a deep mouth cavity in which it is possible teeth made of bone were once displayed. Statues and masks in which the inset teeth still remain are known, but they are even rarer than the inset eyes. Shallow drilled depressions are seen in the corners of the mouth similar to those in the eyes.

In six different places, three on either side of the face, are biconical drilled perforations. That is to say, with a pointed drill, which when revolved drilled a conical hole, wide at the surface and pointed in the interior, the maker drilled three deep depressions on the front and then three from the back on either side, so that each pair of drillings met in the center of the stone and left a perforation through which cords or wires could be passed.

Perforations are found on practically every Mexican mask, but generally only one pair of them. These are interpreted as having been used for suspension or attachment and such was probably the use of the upper pair of perforations of the present specimen. Of the lower two pairs, those on the left side show certain evidences, and those on the right suggestions of copper corrosion. It is, of course, a dangerous matter to draw deductions from the appearance of an object which may have been in the possession of dozens of persons in the last four centuries and subjected to various kinds of treatment, but had the mask been recently excavated, the deduction would certainly be warranted that the copper corrosion was evidence of the former presence of copper rings in the ears.

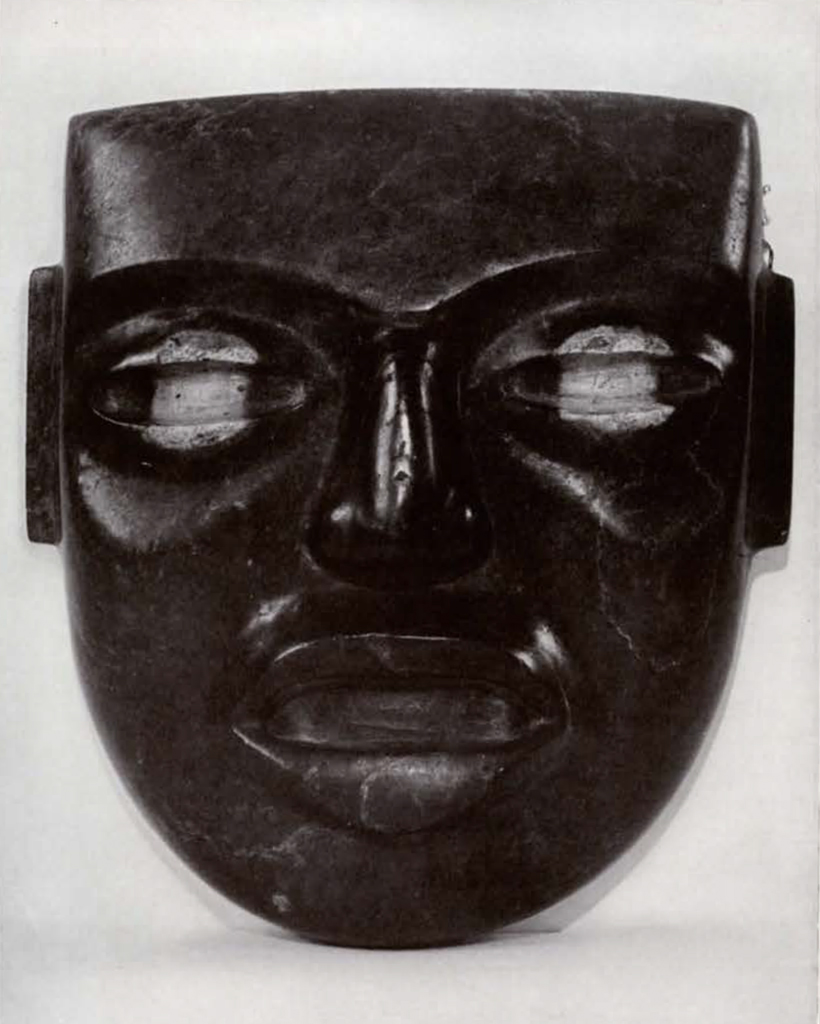

The second mask is somewhat larger than the preceding, 8¼ inches in length and 7½ in width, but the thickness is less, 21 z inches. It is therefore much flatter and consequently less naturalistic than the former. The material is a dark green opaque mottled stone of no great degree of hardness, taking a good polish, probably steatite or serpentine. The eye orbits recede from the supraorbital ridges in a sweeping curve. The eyes form the most interesting feature of this mask. They are represented as elongated ovals, sinking abruptly from the edges of the lids. The interiors of these sockets lack the drilled depressions seen on the other mask. It is possible that eyes and mouth in this specimen also were filled with inset eyes and teeth but this seems improbable in view of the peculiarity of the eyes. In the center of each eye, symmetrically placed, is a spot of light colour in the stone, vertically oval. The two spots are of approximately equal size. In colour they are a light yellowish green with a rather sharp but irregular limit and in certain places a thin band, intermediate in colour, is seen between the light spot and the natural dark stone.

The question at once arises as to the origin of these spots of lighter colour. Although they appear perfectly natural, the author was for some time inclined to think that they might have been produced artificially, possibly by calcining with fire, after the carving of the face. The nature of the spots, however, proves that this could not have been the case. On the main surface both spots were evidently originally circular, indicating that they were actually spherical. They therefore are at their greatest dimensions at the edges of the lids, where they average 1¼ inches in width. In the interior of the eye cavities, however, the width has decreased to a maximum of one inch, indicating clearly that the discolored area was originally in the shape of a sphere before the carving of the eyes was commenced.

Museum Object Number: NA10800

Image Number: 20006

The deduction is obvious, then, that the piece of stone selected for the carving of this mask had in it two spherical spots of discoloration of approximately equal size and that the sculptor cut the mask with the eyes to fit the position of these two spots. Possibly he had had the idea for some time and had long been searching for a piece of stone thus marked. Be that as it may, the mask is unique; I remember no other example like it.

The purpose for which masks served in ancient Mexico has never been satisfactorily explained. It is very doubtful if any of these heavy stone objects were actually worn on the human face; they are too massive, the backs are not properly hollowed out and the eyes and mouth are generally not perforated. There is some reason to suppose that they may have been mortuary and placed with the dead in tombs, but others may have hung in temples as religious objects or in palaces and the houses of the wealthy as ornaments.

Such masks are generally accepted as being from the Aztec period, the last and greatest period of Mexican culture. Some, apparently, were made by Aztec artists, but the specimens under consideration have the appearance of Toltec far more than of Aztec art. The Toltecs were the cultured nation of artisans who preceded the warlike Aztecs in the Valley of Mexico and from whom the Aztecs assimilated most of their culture. While Toltec ascendancy was lost, their blood and their art continued unabated in certain parts of the country such as Texcoco and Tlaxcala, and Toltecs were everywhere employed as skilled artisans. We may therefore consider these masks as of Toltec manufacture.

VI

An Aztec Stone Head

Another important accession of 1925 is an excellent stone head. This, in contradistinction to the Toltec masks, is typical Aztec art and probably dates from a period not long preceding the Spanish Conquest, possibly about 1500 A. D. The material is a heavy black stone which takes a high polish but shows a rough crystalline fracture.

Museum Object Number: NA9269

Image Number: 20024

The carving of the face ends at the chin, neither neck nor body being shown, but above and to the sides of the face is shown in low carved and incised relief a typical Mexican headdress such as is seen on many Aztec statues of the full figure. There is considerable superficial resemblance in this to Egyptian headdresses, so much so that the layman always sees a close relationship, if not actual identity, between them. These resemblances, however, disappear upon a closer comparison.

Across the forehead extends a band, shown in slight relief, on which is a line of six circles or ovals in slightly higher relief. Above this are four narrow horizontal bands or stripes made by incising five parallel horizontal lines. This probably represents either headdress or coiffure just as the line of the circles probably represents a forehead band.

The ears are represented each by a large circle in low relief, within which is a smaller concentric incised circle. This is the conventional method of showing the ear, not only in Mexico but throughout a large part of America and portions of the Old World. It represents the great earrings, made of jade, obsidian or other semiprecious stones, which were inserted in the lobes. These great ear ornaments were especially favored by the chiefs and men of importance and consequently were applied to figures of divinities.

The general appearance of the headdress, and especially the forehead band with its circles, identifies the deity represented as Chalchiuhtlicue, the Goddess of Running Water and the wife of Tlaloc, the great and terrible Rain God. Her figure is one of those most frequently met with in Mexican archaeology.