I

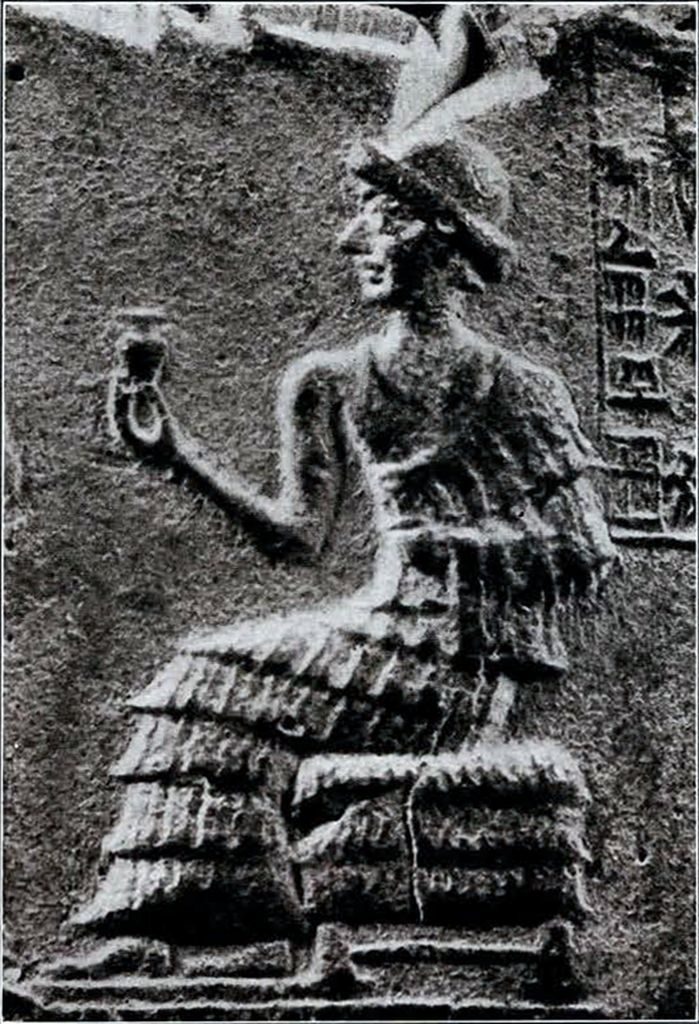

Portrait of a King Who Reigned 4130 Years Ago

Museum Object Number: B12570

Ibi-Sin, the last king of Ur, began to reign in 2210 B.C. The I only portrait of him is one stamped on a lump of clay, taken from the excavations at Nippur in Babylonia and preserved in the University Museum.

Other examples of the discovery during the last twenty years of portraits of ancient kings of Babylonia are as follows, the portrait of King Hammurabi (2000 B.C.) on his famous stela found at Susa; the statue of Gudea, Patesi of Lagash (2350 B.C.) and the relief of Naram-Sin (2600 B.C.) on his stela of victory. All of these portraits are in the Louvre.

The newly found portrait of King Ibi-Sin in the collections of the University Museum is unique in several respects. The lump of clay on which it appears was evidently used to seal a package or receptacle of some kind, as sealing wax is used today. The clay is black in colour; on the underside are seen the imbedded marks made by the knotted strings by which the sealed packet was bound; on the upper surface, on each side, is the impression, very sharp and distinct, of a Babylonian seal cylinder. Between these two seal impressions are two lines of cuneiform writing. On the seal itself is an inscription from which we learn that the seal used was that of the High Priest of the god Enlil, whose name was Sag-Nannar-Zu. We learn further that this seal was a present to the High Priest from Ibi-Sin, King of Ur.

The inscription that is written between the seal impressions gives the name SHULPAE, BANKER. SON OF ERINDAN. This may have been the address of the parcel, or perhaps it was Shulpae the banker himself who sealed the package to prevent its unauthorized opening. We possess some other records of this same banker. His quality of agent or banker is of special interest.

The fact that the seal used in closing the package was a gift from the king is an unusual and important feature, which, together with the scene engraved on the seal, makes a unique document in which we may look confidently for a portrait of Ibi-Sin himself, the deified king of Ur, the last of his dynasty. On the seal cylinders of the Ur school, the special feature is a seated personage wearing a turban. The identity or quality of this personage has remained a matter of doubt. Whether it was the moon god Sin or a deified king was not clear. In the new example the question appears to solve itself.

A seal cylinder cut by order of the king as a gift for his servant, the priest of Enlil (ARAD-DA-NI-IR, IN-NA-BA), is a favour unheard of before the days of the King Ibi-Sin. All other royal cylinders bear witness to the loyalty of the high officers, servants of the King, with the simple words: ARAD-ZU, “thy servant.” Whether this special record of the royal gift means a strengthening of the king’s authority is doubtful. Ibi-Sin’s name portended evil. Under his reign the scepter passed from -Ur to Isin. Was this a last attempt to remind independent patesis or viceroys of their submission to the central power? We know that the high intendant in Lagash, ARAD-NANNAR, received a seal with the same mention (ARAD-DA-NI-IR, IN-NA-BA). This ARAD-NANNAR was not a new name. Under the preceding king of Ur, GIMIL-SIN, he occupied the same high position in Lagash. The name of his father was UR-SHULPAE, a name identical with that of our actual banker. Could it be the same man? The name is the same but the title is different, for in this instance he is not described as a banker, but as a high officer (SUKKAL-MAH) like his son Arad-Nannar. Whether or not he could be acting at times in this capacity and at other times as a banker remains to be proved. In any case we find that in the sixth year of King Gimil-Sin, Ur-Shulpae, the banker (damgaru is the word for banker) was acting as trustee for the custodians of the temple of the deified king of Ur. Temples of the kings Dungi, Bur-Sin and Gimil-Sin were discovered both at. Lagash and at Nippur. The close relationship between the central power of the king and his representatives in neighbouring towns was exemplified by the use of seals with the name and full title of the king together with the name and rank of his local official.

An examination of the seal impression in the Museum, the subject of this article, will show that the scene represented conveys the same idea as the inscription which records the gift. Undoubtedly it represents the king Ibi-Sin in the act of making a gift to the High Priest of Enlil. Among the productions of the Ur school of engravers this seal is one of the simplest of a class representing the introduction of a person to a seated king or deity, or a scene of adoration. Some of the details however set it apart from all other known examples. Among these details is the absence of the usual beard from the seated figure of the king. The seal is a masterpiece of the engraver’s art. Only the best lapidary in the Royal City could cut a seal of such refinement and perfection. The whole design, including the minute inscription, had to be cut in a hard material like onyx, agate or lapis lazuli, used for making seals in ancient Babylonia. The illustration on page 000, showing one side of the lump of clay, is two and a quarter times larger than the original, so that the seal is magnified to that extent.

The engraving shows a scene in the classical style of Ur. Two personages are represented; the servant or official standing in front of the seated and deified king and looking him straight in the eyes. The king, or god, for such in fact he is, holds up gracefully a small twohandled cup or vase. There is a smile lurking on both faces. The meaning is clear, for, up to the present day in the East, to look at somebody is a favour, to avert the face is a mark of disgrace. In the picture the servant stands with clasped hands before his seated master. The little vase filled with precious ointment may be symbolic of the offering received or of the favour granted by the god.

Museum Object Number: B12570

Image Number: 6777

On other examples, where similar scenes are represented, there is an intermediary protecting deity who leads the worshipper by the hand, each lifting his free hand as a sign of adoration. Sometimes there may be a nude attendant or two and stars, crescent moon or other symbols. In contrast to these more elaborate scenes the present engraving attains nearly a Greek simplicity.

Such scenes of adoration existed before the time of the kings of Ur and survived them. The simple fringed garment of the servant, the high flounced mantle of the god belong to a long Sumerian tradition. The last rich frilled mantle, woven to imitate the locks of a sheep’s fleece and identified with the Greek mantle καυνάκης, by L. Heuzey, was reserved to gods and kings worshipped as gods at that time.

The low seat covered with three rows of the same fringed woolen cloth is a characteristic feature of all cylinders cut in Ur and of those that followed the Ur school. In connection with the turban, the new headdress of the gods, it forms a landmark in the field of Babylonian art and history. In the days of the old and down to the last Chaldaean empire, a high conical headdress adorned with several pairs of horns, was the proper dress and crown of the gods. Very archaic cylinder impressions represent gods and goddesses bareheaded or with long hanging hair. The turban is a human headdress from the time of Gudea, the patesi of Lagash, down to Hammurabi. Could it be at the same time a headdress of the gods? How could history account for such a change in religious tradition? We know that King Hammurabi belonged to the new race from the West, the Amurru, and that long before him, many strangers from the same western region, the Martu, were established in Babylonia. At the time of the first dynasty of Babylon new figures of gods appear on the seal cylinders by the side of the old ones. They are standing up armed with mace, dressed in a short garment reaching to the knees and wearing the turban. We have to look upon them as so many figures of the god Martu so long as they were not identified with Adad, Ramman, Ninib or Nergal.

The city of Ur lies on the western limits of the Babylonian plain. But did the kings reigning in Ur from Ur-Engur, who founded the dynasty, down to Ibi-Sin who ruined it, belong to the Sumerian or Martu-Ammuru race? What was their position of deified gods beside the old Moon god Sin, worshipped in Ur? Can we imagine the old moon god wearing the turban, which would be a Sumerian headdress? Gudea was a Sumerian and wore that headdress. Was the new Martu style forced upon the Moon god at the time when the kings of Ur were worshipped as gods and probably identified with him?

It is too early to give a positive answer to all these questions. Whatever was the racial origin of the turban, once a human headdress, it became also a divine headdress. That custom prevailed at the time of the king of Ur and in their own capital. The seated gods wearing turbans may represent the deified kings and also Sin, the patron god. Soon after the dynasty of Ur they certainly represent Sin, as well as some more western gods at the time of the first dynasty of Babylon.

Strong literary tradition speaks of the horns of Sin, which may be simply the symbol of the crescent moon, and of his long dark lapis lazuli beard. All cylinders and seal impressions of the school of Ur and later, represent the seated god wearing the turban and with a long beard hanging on his breast. Our clay relief is the only known example where the seated god is beardless. It cannot be a goddess. We have no examples of female figures wearing the turban and the complete statue of Gudea is the standard evidence of an entirely shaven man wearing the turban. The worshipper of our relief has the same shaven head, and even the same gesture of clasped hands and the same fringed mantle, as Gudea in front of his god. It will be an easy step to identify him with the high priest of Enlil in Nippur. Last of all, the beardless king god, so near to humanity, is not entirely shaven as befits liturgical cleanliness. Just a lock of hair is playing on the forehead and on the neck. The large set eyes, the high cheek bones, the curved nose, the thin lips, the firm and round chin, complete an interesting attempt to portray King Ibi-Sin the last king of Ur, with a necklace and arm band as becomes his majesty.

The inscription on the seal reads as follows:

powerful hero

King of Ur

King of the four regions, has given it

priest of Enlil

his servant

The cuneiform inscription on the clay reads:

Urd Shul-pa-e- damgar

son of Erin-da-an

II

A New List of Kings Who Reigned From 3500 to 3000 B.C.

Chronology is the framework of history. The names of the kings and the length of their reigns, the relation of father and son, the dynasty to which they belonged and the city which became their capital, the total number of kings and years of one particular dynasty and, best of all, fully developed lists of succeeding dynasties, are a leading light in the obscure path of the student of ancient history. Anything bearing on these subjects is a most valuable document for the scholar, the archaeologist or any man interested with the problem of origins.

Among the few uncatalogued tablets in the Museum collection there has come to light, during the past summer, a fragment from Nippur which is of unusual importance in this connection for it is part of a chronological tablet that fills a gap in the early history of Babylonia. It begins at a point prior to 3500 B.C. and comes down to 3000 B.C., covering a period of more than 500 years and connecting up with other chronological records that have come to light from time to time.

Museum Object Number: B14220

By degrees, thanks to the documents published in the last ten years, we are reconstructing Babylonian history over the third millennium back to the legendary times of the kings after the flood. The part played in this reconstruction by the Babylonian Expedition and excavations in Nippur cannot be overrated. Indeed, Nippur and its temple towards B.C. 2000, at the time of King Hammurabi, the very time when Abraham started on his long wandering career, appears more and more as a centre of religious and intellectual life. At Nippur records of the past used to be stored, preserved and compiled, in form of statues, slabs of stone and votive objects covered with inscriptions and reliefs, recording the names of the kings, their wars, their victories and their offerings to the gods. That ancient institution, with all respect and allowance for time and place, might compare with the modern abbeys of Westminster and St. Denis. A collection of those inscriptions on a large tablet done by a scribe of the temple is among the most precious documents preserved in the Museum. All of the inscriptions on that tablet concern three kings of the dynasty of Akkad, B.C. 2600, SARGON, RIMUSH and MANISHTUSU.

Besides the newly found fragment, the collection in the Museum contains other tablets of the same class. One of these is one-half of what must have been the standard work on chronology. It was a work complete in twelve columns, six on the obverse from left to right and six on the reverse from right to left. Column 12 is accordingly the reverse of column 1 and column 11 is opposed to column 2. This half tablet gives on the obverse and reverse the beginning and the end of the chronological scheme down to 2000 B.C. but gives no clue to the length of time covered by the missing portion or how to connect the fabulous kings who succeeded the Flood with those of the dynasties of Ur and Isin. Its text extends across columns 1, 2 and 3 on the obverse and includes columns 10, 11 and 12 on the reverse. Before the gap it fixes the dynasties of Kish, Uruk, Ur and Awan; after the gap are given the dynasties of Akkad, Guti and Isin.

The new fragment fits in the gap. It represents a portion of the text of columns 4 to 5 of the obverse and 7 to 9 of the reverse, with a few signs of columns 3 and 10, very useful to link it up with the text of the tablet just described. Unfortunately it does not belong to the same identical tablet. Their thickness is different. It is still more damaged. Top and bottom of all the columns are broken off.

Despite necessary reservations in presence of a mangled text, the great interest of the new fragment lies in the fact that it restores the main lines of Babylonian chronology as set down by tradition among the scholars of Nippur about B.C. 2000. (The Greek tradition of Abydenus and Berosus must be traced back to it.) Four new dynasties of Kish, Hamazi, Adab and Mari will take rank soon after those of Ur and Awan and before those of Upi, Kish, Akkad, Guti and Isin. We learn, too, the names of the first rulers of the Guti: Imbia, Ingishu, Warlagaba and larlagarum, four out of a total of 21 kinds who occupied the land 124 years and 40 days. The old Sargon, founder of the city of Akkad, the devotee of the god Zamama, was the father of king Rimush and the grandfather of king Manishteshu. He reigned 55 years and his son 15. King Lugalanni reigned 90 years in Adab, and Ansir, the first king of Mari, 30 years.

Museum Object Number: B14220

This new and welcome piece of information must not blind us to the fact that absolute reliable chronology is actually out of the question, not only because a legendary number of years is attributed to the kings of the first dynasty of Kish (some 6, 7, 8 or 9 hundred years each), or because any attempt to supply by indirect computation the missing portions of the text would prove fruitless, but because the texts so far published do not agree in all details. Whether the various readings have to be traced back to the old scribe, or to the modem copyist has to be further established. Poebel’s tablet attributes 125 years to the Guti dynasty where we have only 124.

Another famous chronological tablet published by V. Scheil is a full list of the kings of Upi, Kish, Uruk, Akkad, Uruk down to the invasion of the Guti, practically identical with the middle portion of the Nippur tablet. It may be an early witness of the same chronological tradition about B.C. 2400, or more probably a recent copy of the same Nippur work in three tablets instead of one; Scheil’s tablet being number 2 of the series. Anyhow the copy has peculiarities of its own. The dynasty of Kish with its 8 kings and a total of 586 years, is supposed to have been founded by a woman, Azag-Bau, who, being queen, reigned 100 years. Our fragment ignores Azag-Bau except as the mother of the first king of Kish, Basha-Enzu. His son and successor, Ur-Zamama, reigned 20 (or 80) years according to the new fragment and 6 according to Scheil’s tablet. No doubt that the total number of years of this dynasty should appear very questionable.

Summing up the new chronological data we may safely establish the following scheme: beginning of dynasty of Isin about B.C. 2200; Ur, 2300; Guti, 2425; Akkad, 2650; Kish, 2875; Upi, 3000; before which we have to place at least 8 more dynasties of Mari, Adab, Hamazi, Kish, Awan, Ur, Uruk and Kish, about B.C. 3000 to 4000.

Translation of the Text

- reigned [30 years]

[Elu]lu

reigned [25] years

[Balu]lu

reigned [36] years

[4] kings

ruled [120+] 51 years

[Ur] was defeated by arms

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . - [4 or 6 ?] kings

ruled 3600+192 years

Kish was defeated by arms

the kingdom

passed to Hamazi

In Hamazi

[ ]-ni-ish

became king

and reigned [ ] years

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . - passed to Adab

In Adab

Lugalanni established it.

being king

he reigned 90 years.

1 king

reigned 90 years.

Adab was defeated by arms.

the kingdom

passed to Mari.

In Mari.

Asir being king,

reigned 30 years.

[ ]-gi son of [Ansir]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . - reigned 99 years.

Upi was defeated by arms.

the kingdom

passed to Kish.

In Kish

Basha-Enzu

son of Azag-Bau

being king

reigned 25 years.

Ur-Zamama

son of Basha-Enzu

reigned (80?] years

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . - [liba]tor, devotee of

Zamama.

king of Akkad

who founded Akkad

being king

reigned 55 years.

Rimush son of Šar-ru-ki-in

reigned 15 years.

Ma-ni-iš-te-šu

[son of Ri]mush

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . - The people of Gutium

had no king.

Imbia ruled 5 years.

Ingishu,

ruled 7 years.

Warlagaba

ruled 6 years

Iarlagarum

ruled [3 ?] years

. . . . . . . . . . - ruled [ ] years

21 kings

124 years 40 days.

The people of Gutium

was defeated by arms.

the kingdom

passed to [ ]

. . . . . . . . . . - [son of Gimilili]shu

[reigned 21] years

[Ishme-Da]gan

[son of Idin]Dagan

. . . . . . . . . .

L. L.