Wherever there is in the world a City speaking the English language, with wards, with municipal government consisting of Mayor, Aldermen or Common Council representing the wards, there you have, on one scale or another, a model of London. These institutions, this system of municipal government was introduced in London in the twelfth century, was copied by all other cities and towns in Britain and in turn by every City and town founded by emigrants from Britain. It was brought about in London, not without some foment, not without some conflict with established authority, not without divided opinion. It was not done without invading the rights of the barons, the Church and the King, but it was done peacefully and quietly and the new order was created without violence out of orders already existing and formed from elements long planted in London. It was brought about by the general desire and in the following way.

At the very end of the Saxon Period and the early part of the Norman Period, London was divided into Manors or private estates, each of which was owned by a family whose hereditary title to the land carried with it the prerogatives of rulership. The head of the family was Lord of the Manor. His estate was his kingdom and his revenues were derived from the productive industry of the people living under his protection. He administered the Manor as a private property but with regard to the interests of its inhabitants whose rights were protected by immemorial customs that recognized the authority of the Lord of the Manor but qualified his ownership of the land. If the land were waste, he could do with it as he pleased but if it were in use, his power over it was limited by custom. The Lords of the Manors in London were styled Aldermen and -they were known as the City Barons but they were not nobles. Each Manor was a separate and independent estate. The corporate municipality did not yet exist and the hereditary proprietors constituted themselves the ruling council of London with the King as the only overlord. Within the Manor was held the Wardmote or assembly of all the inhabitants of the Manor. The voice of all the people found united .and common expression in the Folkmote, a meeting of all classes of people within the City. The meetings of the Folkmote took place whenever the great bell in Saint Paul’s bell tower was rung to call the citizens together. They assembled at the open space beside Saint Paul’s Cathedral, a space that was common ground and not included in any of the Manors. At the Folkmote anyone could speak and there matters of general concern were debated and decided. There was a Sheriff for the whole City whose duties had to do with defence and who led the citizens when they had to make common war. The Sheriff was elected by the citizens themselves at the Folkmote. There was a civil authority called the Protreeve who was appointed by the King. There was also a Bishop who exercised ecclesiastical authority over the City and who was an Alderman on account of the Church property in London. The Bishop and the Protreeve were joint rulers of the City, one wielding civil authority and the other representing the authority of the Church. This general statement is based partly on conjecture, for exact knowledge of the government during Saxon times and at the beginning of the Norman regime is very meagre and incomplete. In addition to the forms of government I have mentioned there would seem to have been other sundry powers exercised by a few within the City who bore a leading part in the government. Gradually changes came about; one by one the Lords of the Manors disposed of their titles to the land which became divided up among many owners; their families became merged in the general population and private ownership of the Manors disappeared, without however obliterating the boundaries of these estates, which have remained fixed to this day. When the hereditary Alderman or Lord of the Manor disappeared the people living on the estate began to elect their Alderman for life. This situation was not altered at the Norman conquest for it was one of the conditions that the Londoners made with William, that nothing should be changed. In the twelfth century, during the reign of Richard I, events so shaped themselves that elements of municipal government, already long enduring, were adjusted to the changed conditions brought about by the growth of the City. Old institutions put forth new ideas and took on new forms. London became a corporate body through the action of the citizens, supported by the Barons, the Bishops and all the magnates of the realm, for about this time London began to associate itself closely with the country and became the head and centre of English life.

In the change that came about in 1191 London became a municipality though the fact was not set forth as yet in any charter. The great event took place while Richard was absent on the Crusade and when his unpopular Regent Longchamp was deposed by the citizens. It was decreed that the new order should hold during the pleasure of the King. When Richard returned, all went well enough, but Richard never recognized the Mayor, neither did he interfere with his office. John, however, on his accession recognized the Mayor and gave the City a Charter embodying the new order. In fact the citizens had made sure of John beforehand, for while his brother Richard was in Palestine and he wished to make good his claim to the Crown in case of the King’s death, the Londoners at a meeting of the Folkmote received John, the Barons and the Bishops and obtained from each in turn a solemn oath to support the new order in the City. Then they administered the oath of fealty to King Richard.

The important part of the agreement was the right which the citizens successfully claimed of electing their own chief magistrate whom they called the Mayor. The Manors, retaining their old boundaries, now became the Wards, and the Aldermen, elected for life, succeeded to the old hereditary Aldermen, the Lords of the Manors.

The Mayor took over from the Merchants Guild the regulation of trade with full power and authority to enforce his ordinances. He also kept the peace and maintained order within the City and he presided over a central court that replaced the several judicial bodies having separate jurisdiction. He was supported by two sheriffs, bailiffs, officers and servants, and he was responsible for the general welfare of the City.

The Common Council started as a body of twenty four citizens chosen by the Mayor to aid and advise him. In the thirteenth century this body gave way to the Common Council elected by the Wards, for the Wardmote still retained its full force and met under the Chairmanship of the Alderman as the chief magistrate of the Ward.

After the establishment of this system of municipal government with the Mayor as chief magistrate presiding over a Court of Aldermen, the old Folkmote or parliament of citizens that from time immemorial had met in the open air at Saint Paul’s, continued to meet but its power dwindled until with the election of a Common Council by the wards it disappeared altogether, or survived only in the form of an outlet for agitated minds, a forum where any citizen availing himself of the right of free speech might air his views in public. Doubtless the tradition of the Folkmote clung to Paul’s Cross and may be recognized in the controversies that were fought out there. It was a battleground of the Reformation and the legend of Paul’s Cross is one of the most significant in London. Transferred to the windy corner of Hyde Park that legend remains today one of the most remarkable survivals in the world and one of the most wonderful sights to be seen anywhere. I have already suggested that the modern usage, localized where space affords, is a direct inheritance but whether or not we choose to regard it as a survival of an old institution associated in early times with Paul’s Cross, the fact remains that the Hyde Park practise illustrates a latitude in the use of speech in public places that is not peculiar to our generation.

The Folkmote never was officially dissolved. It might be argued that its legitimate successor was the meeting in Common Hall, the Guildhall, because at first the election of the Mayor was made by the whole body of citizens assembled in Common Hall. In a sense that is true, for the Common Hall assumed the authority of the Folkmote which was succeeded or rather superseded by the Common Hall, but nevertheless the old open air Folkmote continued to meet as before though apparently without authority. There is no record of a termination of these meetings.

The first Mayor, elected in 1191, was Henry Fitzalwyn of London Stone, so called because his house stood beside that ancient landmark. It was a century later that the title of Lord Mayoi was assumed without affecting the nature of the office.

Meantime, long before the creation of the office of Mayor and the municipal system that still prevails, we hear much of the City Guilds. These guilds were at first associations of craftsmen or of merchants united for charitable, social and religious purposes. Each craft had its guild, with entrance fees, governing rules, provisions for the sick and the unfortunate, and masses for the souls of the dead. To these functions the guilds began to add the regulation of wages and hours of work, the training of apprentices each of whom must belong to the guild and serve seven years under the master to whom he was bound. The guilds also assumed the right to set the standard of workmanship, always with a view to the improvement of the craft. Bad work was condemned and destroyed and penalties were imposed on inferior craftsmanship. The masters and the journeymen were members on equal terms but the time came when the masters or employers began to control the guilds for their own benefit—fixing hours and wages and regulating the conditions of labour without consulting the workmen in the guild. This led to varying degrees of disorganization.

At the same time that the Craft Guilds took their rise, there arose the Merchant Guild, rich and powerful, regulating the trade of the City. At the creation of his office it became one of the duties of the Mayor to adjust disputes between the guilds. Such disputes were common, for the guilds watched each other jealously lest one should overreach the other. From the first the Merchant Guild was unpopular with the Crafts. Among its members were the hereditary Aldermen who, being themselves engaged in commerce, made common cause with the merchants of the City and united with them to form a governing class. The Merchant Guild therefore was suspected of putting most of the burden on the Crafts. This led to a long struggle for it was a long time before they learned to trust each other and unite for the common good.

There came a culmination of the feud between the employers and the men, within the Craft Guilds themselves. The men formed combinations of their own—unions. There were strikes. The workmen were resolved to get the management into their own hands. The Mayor and Aldermen pronounced the new combinations illegal and ordered the men back to their guilds or companies, the only associations of labour that were licensed in London. The revolt of the men against their employers, determined though it was, failed utterly. That was six hundred years ago, and the same subjects are being discussed today. The struggle caused a general disorganization and demoralization of the guilds for a time till they were reformed as Companies under ordinances approved by the Mayor. These Companies continued from that time forward to exercise power and successfully to control the craftsmen. They consolidated their corporate power and confirmed their authority over their respective crafts and their share in the administration of the City. That share they have always maintained and today the City Companies are a component part of the Corporation.

It is natural that in such a long continued existence, some of the prerogatives and powers of the Companies should have become obsolete. On the other hand wherever these ancient rights are adaptable to modern business, the ancient franchises have full force. As an example we may take the Vintners Company. It is so old that its origin is lost in antiquity. Probably it existed as far back as the making and selling of wine. The monopolies and powers of the Vintners Company may be illustrated by the fact that its members alone could import, buy or sell wine in the City of London. The Company had power to regulate that importation and sale, and through its members controlled the entire trade in wines and spirits. The members required no license except the license of the Company. The Company in its corporate capaCity had power to enter the premises of any member, inspect his stock, condemn such part as was below standard and inflict penalties and punishments for infringement of rules and for failure to observe the amenities of the trade. Here is a case from the records of the Company.

John Right ways and John Penrose, taverners, were charged with trespass in the tavern of William Doget, in Estchepe, on the eve of Saint Martin, and there selling unsound and unwholesome wines, to the deceit of the common people, the contempt of the King, to the shameful disgrace of the officers of the City, and to the grievous damage of the commonalty. John Rightways was discharged, and John Penrose found guilty; he was to be imprisoned a year and a day, to drink a draught of the bad wine, and the rest to be poured over his head, and to forswear the calling of a vintner in the City of London for ever.

From time immemorial the Vintners Company has enjoyed the exclusive right of loading, landing, rolling, pitching and turning all wines and spirits imported to or exported from the City of London. Its tackle porters handle all the wines and spirits that arrive in London and all persons employing these tackle porters are indemnified by the Company for any loss or breakage that may be caused in the handling.

The Company through its members claims today the privilege of selling foreign wines without license throughout England. The Company exercises control over its members, it hears complaints, issues summonses, calls witnesses, takes evidence, adjudicates at its discretion. A pillory was formerly kept in the Hall for offenders. The extreme penalty is expulsion from the Company. Liverymen and their widows are entitled to pensions and donations in case of need. The Hall of the Company stands in Upper Thames Street.

The wealth and standing of some of the wine merchants may be illustrated by the example of Henry Picard, a Vintner, who in 1363 at the return of the Black Prince from France, feasted at his own house a company that included five kings and many nobles, besides the Black Prince. The kings were Edward III of England, John II of France, prisoner of the Black Prince, David king of Scotland, the king of Denmark and the king of Cyprus. After the banquet Picard entertained the kings by playing dice with them or with as many as would try their luck with him. His wife, the Lady Margaret, at the same time entertained the queens, princesses and great ladies in the same manner in her own apartment. Picard returned his winnings and distributed rich gifts to all his guests and their retinues. The Vintners Company still drinks the toast Five times Five in memory of Picard’s feast of five kings.

The Hall of the Corporation of the City of London is known as the Guildhall, where the election of the Lord Mayor takes place annually, where the State banquets of the Corporation are given and where the Lord Mayor presides at many picturesque ceremonies. The original Guildhall of unknown antiquity was replaced in the fifteenth century by the present building. In the Great Fire it lost its roof which was then restored by Christopher Wren. In the gallery of the great hall are the two uncouth wooden figures of Gog and Magog which were made to replace two similar figures that were burnt in the Great Fire and that used to be carried in the Lord Mayor’s Procession. Who and what they actually represent cannot be stated in any satisfactory terms.

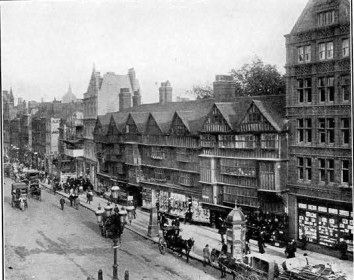

Image Number: 22668

The origin and antiquity of the name Guildhall are unknown, but the name itself would suggest that it was originally the Common Hall of the ancient City Guilds. The position of the Guilds is so important that I must restate that position at the risk of being tedious. The Romans had their trade associations or fraternities for the mutual help of their members and for social purposes. In London these Roman trade associations became merged in the Saxon Guilds and we have seen how these Guilds were transformed into the Companies after the struggle between the masters and the men. They are officially known as the Livery Companies of the City of London because the members wear distinguishing liveries with their appropriate insignia. There are seventy three of these Livery Companies with their regular order of precedence, exercising both separately and collectively a powerful influence and enjoying monopolies set forth in ancient charters granted by early Kings.

Some of the trades represented by the Guilds are extinct, such as that of the Bowyers, and that of the Fletchers, the makers of bows and the makers of arrows, but that does not mean that these Guilds are extinguished for they retain their corporate existence, their ancient civic rights and their social functions. All of the great Companies and most of the others own their halls that are among the most interesting features of the City. Some are very rich, the properties that they have owned in the City from time immemorial having acquired an enormous value. Their incomes are devoted to technical education, scientific foundations, hospitals and other charities and good works.

Among the principal Livery Companies are the Goldsmiths, Ironmongers, Clothworkers, Fishmongers and Vintners. These and others to the number of twelve are the Great Companies and take precedence of all the others. Membership is by inheritance and by special election. It is not necessary to be engaged in trade to be a Liveryman. The Prince of Wales for example is a Fishmonger—a Liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Fishmongers, having been received in that honoured position with appropriate ceremony. But you or I could not break into the Worshipful Company of Fishmongers no matter how many fish stories we might tell. But if we sold fish successfully for about five hundred years we would inherit our membership even though we might have retired from the business several generations ago.

The Lord Mayor is elected annually on Michelmas Day. On the sixth of November he is sworn in at the Guildhall and on the ninth of November he proceeds in State to the Royal Courts of Justice to be sworn in before the Judges. His progress on that occasion is attended by the gorgeous procession known as the Lord Mayor’s Show that in earlier times took place afloat on the Thames.

The qualification of the electors who elect the Lord Mayor, the two sheriffs, the chamberlain and the minor City officials is that they must be liverymen in one or another of the City Companies and freemen of London. The method of election is as follows. The liverymen elect the two sheriffs each year from the members of the Court of Aldermen, the elected sheriffs retaining of course their membership in that court as representatives of their respective wards. To fill the office of Lord Mayor the liverymen select annually two Aldermen who have passed the Chair, that is who have held the office of sheriff. The Court of Aldermen is then under obligation to choose one of these two to fill the office of Lord Mayor for the ensuing year.

The election of the sheriffs takes place on Midsummer day of

each year and a more interesting and colourful ceremony is perhaps not to be found even in London. The ground in front of the Guildhall is for the time being enclosed by a barrier in which are twenty two gates. Above each of the twenty two gates are written the names of certain guilds, the seventy three guilds being divided into groups corresponding to twenty two letters.

Over one gate would be seen

- Armourers

- Apothecaries

Over another gate would appear the legend

- Bakers

- Barbers

- Basketmakers

- Blacksmitsh

- Bowyers

- Broderers

- Butchers

The third gate would display the following

- Carpenters

- Clothworkers

- Cooks

- Coopers

- Cordwainers

- Curriers

- Cutlers

Another gaet would be distinguished by this array of names

- Farriers

- Fanmakers

- Feltmakers

- Fishmongers

- Fletchers

And so on through the alphabet.

To be admitted to the ceremony of electing the sheriffs, you must be a member of one of the 73 Guilds and also a freeman of the City.

Behind the twenty two gates stand seventy three formidable officials in a row, in seventy three different liveries, with a lot of gold lace and with maces in their hands—”terrible as an army with banners”. They are the beadles of the 73 Companies, they are there to recognize the members as they arrive and they constitute the first line of defense.

We will now suppose that you are a Lorriner and you are going to the election in company with your friend the Skinner. You may not know exactly what a lorriner is and your friend the Skinner may earn his living as President of the Anglo-Silurian Oil and Aerial Navigation Company, Limited; but these details are of no consequence—you are going to the Guildhall to elect the Sheriffs. When you arrive in front of the twenty two gates, you proceed to the gate that has Lorriners written over it and your friend separates from you and approaches the gate marked Skinners. If the beadle of your Company, mace in hand, recognizes you, you are admitted. That recognition is your passport without which you do not vote at that election. If he should fail to recognize you and you should proceed to make an assault upon the gate, the entire first line of defense would be ready to concentrate its resistance at that point to repel your attack. Having been recognized however, you proceed to the door of the Guildhall, pass through the porch and enter the Great Hall. Its floor is strewn with sweet herbs that lie with a special profusion on the dais on which the high officials are to sit in State. Presently there is a movement across that dais where, in a flourish of red and gold, scarlet and purple, and a flash of jewels, with sword and mace borne upright before them, the Lord Mayor, the retiring Sheriffs, the Aldermen who have passed the chair, and the whole list of Aldermen enter in procession and take their seats. They are robed and capped and trimmed with fur. Then enter the Town Clerk and the Recorder in wig and gown, carrying bouquets. When all are seated, the Common Crier raises his voice.

“Oyez! Oyez! All ye who are not Liverymen, depart from this hall on pain of imprisonment. All ye who are Liverymen and freemen of the City of London, draw near and give your attendance. God save the King.”

I cannot describe the method of election or the scenes that attend the voting. I have no title to be present and the accounts I have been able to extort from two or three voters whom I happen to know were disconnected and unsatisfactory. It was obviously rather stupid to be curious about anything so commonplace as an election. For a good description I can refer you to a very helpful and entertaining book, More About Unknown London by Walter George Bell, a Londoner. To that description I am indebted for much of my information about the election of the sheriffs.

Besides the Sheriffs, there are elected on the same day certain other officials, among them two Bridgemasters and seven Ale Conners. The former apparently have no longer anything to do, but the Ale Conners are understood to taste and judge the quality of all the ale drunk in London and to keep an eye on the brewsters. You may not know that brewster is the feminine of brewer or that in former times ale was made by brewsters. Brewing was a feminine occupation.

The Aldermen are elected for life by the Wardmotes. The Wardmote consists of all the inhabitants of the ward. Its meetings are called by the Alderman as the chief magistrate and presiding officer of the ward. Its function is to promote the welfare of the ward. It is the same identical body, meeting in the same identical place for the same identical purpose as that which met under the leadership of the Lord of the Manor before the Norman conquest.

The Common Council is elected annually by the Wardmotes, the number from each ward being proportionate to the population. The Court of Aldermen and the Court of the Common Council are the advisers and assistants of the Lord Mayor who presides at their meetings in the Guildhall. The position of the Lord Mayor in the City of London is altogether extraordinary and without parallel. The remarkable privileges that pertain to his office and that have been most religiously guarded for so long are all of great antiquity, and in part at least derive their origin and significance from times long before the creation of the office with which they are identified. These peculiar privileges of the Lord Mayor are as follows. His position in the City, where he is second only to the Sovereign. His right to close Temple Bar to the Sovereign. His right to be summoned to the Privy Council on the accession of a new Sovereign. His holding the keys of the Tower from the hand of the Sovereign and his receipt four times a year from the Sovereign of the password of the Tower. His position of Chief Butler at the Coronation Banquets.

London always claimed a separate decision in the election of a King. Its citizens did not deny to the rest of England the same right to make independent choice and they never interfered with that right, but it was always understood that the choice of all England outside London was not of necessity London’s choice. In other words London always claimed the right of separate election. Therefore London might have one king and the rest of England another. This happened when London elected Edmund Ironside in the century preceding the conquest and when they elected Stephen in the century after that event. But these were not the only occasions when London exercised its right to elect a King.

Does this claim to separate election account for the right of the Lord Mayor to be summoned to the meeting of the Privy Council on the accession of a new sovereign? I do not know.