I never saw myself as separate or different as a child growing up in Denver, Colorado. Perhaps it was because my classmates in Headstart were a diverse bunch. Perhaps it was because the powwows my family attended had both Native and non-Native people coming together. Perhaps it was because Denver was a mixed race city. I’m not sure.

Patty Talahongva at age 2, and with her sister Berni. In the early 1960s, her parents moved to Denver from the reservation so that her father could find employment.

My family had moved to Denver under the U.S. Government’s relocation program that targeted the Hopi and Navajo people in Arizona, and many other tribes across the nation. The idea was to move the younger generation off the reservations and into cities where they could “assimilate” into mainstream society. The more sinister goal may have been to wipe out the reservation system and kill the Native cultures. The program gave the families money to move, $19 in my parents’ case, and set up host families in each city to help those relocated find a place to live and get jobs for the men. My father was hired at a bakery. We lived in Denver for nine years; my younger sister and I were born there. Then my family moved back home to Arizona and closer to our reservation so we could participate in our Native culture and religion.

In Arizona I was around more white people than ever before and that’s when I started to see some differences. I have one clear memory of something that happened when I was about seven or eight. My friend, a white girl, brought her cousin over to play. Her cousin was a redhead and quite fair. She had freckles and she hated them! I didn’t think they were so bad until she said in disdain, “Well, at least I have a lot of freckles. You’re just one big freckle!” I remember looking at my arm and wondering, “Is that what it is? That brown color? A big freckle?” I decided I didn’t like her and I didn’t like being called a freckle. Image matters and I reassured myself that I was “okay” even when boys pulled on my thick black braids and teased me about having “horse hair.” Yet, in my teens I was amused to see my peers frantically trying to get a tan while I just turned a nicer shade of mocha as they sunburned.

All my life I’ve been mistaken for being Latina or Asian. I see blank stares when I tell people I’m Hopi. Then I have to add, Native American. I’ve been told so many times that I “speak English so well!” Unfortunately, English is my first language. Neither of my parents spoke English for the first seven years of their lives. Learning English was a forced and painful process for them, something they wanted their children to avoid. As a result they spoke only English to us, their six children. It’s a lifelong effort for me to learn Hopi, a beautiful and complex language.

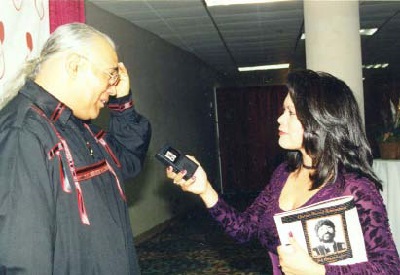

(Right):In 2006, she interviewed Wilma Mankiller, Chief of the Cherokee Nation.

Besides speaking Hopi, it’s also important to me to live Hopi. That comes with great responsibility if one accepts the duties of being Hopi. The term “walking in two worlds” is often used to describe this process. I cringe when I use this phrase but it does convey a certain sentiment. I don’t concentrate on it as some might imagine. It’s more like the way most people walk down stairs without looking at every single step…you just know where to put your feet. However, being Hopi does require me to actively choose to perform my cultural duties. This means being aware of our ceremonial cycle and knowing when I need to prepare and participate in sacred ceremonies. When I was a teenager and went through my first initiation into the Hopi way of life, I had to wear a small eagle feather in my hair, even when I went to school. The feather drew lots of attention and snickers from other kids about me being an Indian. I had to ignore and not resent the kids making those snide remarks because the initiation ceremony included meditation and prayer and acceptance of more adult responsibilities, including tolerance.

My career in television news meant that I often had to work when Hopi ceremonies were taking place. It was a tough time for me, but I had to have a job. I was able to help my sisters with funds for travel, for food, and other basic necessities. Many times I would work Christmas and Easter so that I could take other days off that had religious significance for me. I also made the choice to live and work in Arizona so that I would be close to my reservation for ceremonies I wanted to attend. I refused to consider offers to work in other larger TV markets because of the distance. I don’t regret that because being Hopi is important to me. One day, like many Hopis, I will move back to my reservation.

When I chose to marry a white man, we discussed my culture and his supporting role in ceremonies and other aspects of my culture. He promised to help raise our children in the Hopi way and he did. When we divorced, he promised to continue to support our son in the Hopi way, and he has. We raised our son with the values of Hopi and the teachings that included not harming natural things. When I found my little son and his friends tearing off tree leaves and small branches, I asked him why they were doing that to something that was alive. I asked him if they would pull the hair off of our dog. He said no. I told him the tree was also a living thing and it wasn’t good to harm it by pulling off its leaves, that Hopi boys should respect all life. He got the message. It hurt me greatly when he was about five and experienced his first racist remark. We were at a mall and a friend had bought him a bag of plastic soldiers and Indians. My son poured them on the floor and was busy playing when another boy came over and asked to play. My son was happy to have company, but it soon turned sour when the boy said, “Let’s put all the good guys in this pile and all the bad guys in another pile!” One guess as to who the “bad guys” were. I was both sad and proud when my son said, “Indians aren’t bad!”

While I “walk in two worlds,” my son IS “two worlds.” We both manage this quite comfortably. We work, go to movies, eat out, and enjoy a wide circle of friends in the Phoenix metropolitan area. When we have our ceremonies we plan accordingly. Our drive to the reservation takes four hours one way. If need be, we isolate ourselves for the duration of the ceremony by staying on the reservation. This helps us keep the integrity of the ceremony and our intentions pure. It is important to note that when Hopi people pray, we pray for everyone and all living entities. We’ve always known the world is round, and our prayers are for people around the world.

Our Hopi ceremonial cycle lasts for a full year. In December we have Soyalang, a time for blessings. It’s usually seven days long. Sometimes we only make it out for two days, due to my work. Then we prepare for Powamuya, which lasts around 21 days. This is the official start to our New Year and takes place in February. The men are in the kiva (an underground room) praying while the women take care of the home and prepare the meals. It’s not at all sexist like some folks may think when they hear about the roles Hopi men and women have. Hopis recognize the value and contributions of both the men and the women. After the initial ceremony is completed we have another month of katsina dances and prayers which are held in the kivas and are mostly closed to non-Hopis. Spring brings the katsina dances in the plaza, which are open to non-Natives. Each of these religious dances brings a lot of responsibility to the hosting families and everyone involved. The final katsina dance is the Nimanti, also known as the Home Dance. This usually occurs in late July or August. You can learn more about these ceremonies because in the 1800s several anthropologists came to the Hopi reservation, forced their way into the kivas, and wrote about what they witnessed. It was an invasion of our privacy and disrespect of our religion, but what can be done about that now? I would warn the reader not to take things they might read literally, because much of the beauty and meaning of the ceremonies was lost in translation. The non-Hopi anthropologists didn’t understand what they were experiencing.

I am happy to share as much of my culture and religion as is appropriate. When people push me for greater detail, I simply ask, “Why? Why do you need to know?” Many religions have taboos on revealing all that takes place. Or only granting information when the person asking earns that right. It’s simple respect for another person’s religion.

I consider it a great blessing to have been born a Hopi. If I was not a Hopi, I could not convert to become one. In fact, I know of no American Indian tribe that fought wars over religion. We recognize that other people have their own ways of worshiping and we respect that. Therefore, we don’t try to preach to and convert others to the Hopi religion. I feel that since I am Hopi, it is my responsibility to carry on the teachings, the culture, and the religion so that my children and grandchildren will also have the opportunity to be Hopi.

As you will see in the Penn Museum exhibition that opens in 2014, I am not the only Native person who feels this way. Many of us are doing what we can to carry on our traditions, culture, language, and religion. It just gets harder with each generation as we compete with so-called modernday conveniences. I think about my ancestors who fought so hard to stay alive and who kept our culture going, and I wonder if I am living up to their standards. Each generation will have to make that choice as well. For me, it’s a choice I make every day, to live as a Hopi.

Eskwali! That means “thank you” in the dialect of my village, in the feminine pronunciation. I’m thankful you have taken the time to read this essay.