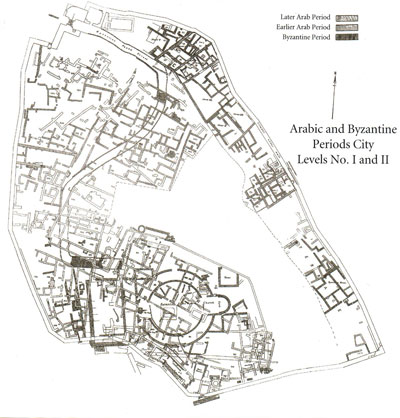

The Roman city of Scythopolis extended to the south of the tell, with broad colonnaded streets and large public buildings, including baths, a basilica, a theater, and an amphitheater. The monumental temple of Zeus Akrios, excavated by the Penn Museum team, was the only significant structure on the tell, apparently connected to the city below by a monumental staircase. After the advent of Christianity, it was replaced by the Round Church, discussed in this issue, and elsewhere on the tell a residential neighborhood developed. The excavation of this area quite literally shed light on domestic life with the wealth of lamps and lighting devices uncovered.

During the Late Antique and Byzantine periods (ca.250–750 CE), oil lamps illuminated communal spaces and served as votive offerings at holy sites. Along with a couch and table, they were also considered among the most essential furnishings for a house. The excavation of Beth Shean yielded a rich trove of lamps dating from the Roman period to the years following the Arab conquest in the mid-7th century CE. These objects help shed light on daily life and systems of belief in Byzantine Palestine. Late Antique lamps could be made from expensive materials like bronze or silver. Such lamps often adorned wealthy public institutions and the private residences of the affluent. Frequently formed into zoomorphic shapes, metal lamps were typically freestanding, although some were also fitted with hooks for hanging or included sockets in their bases for placement on lampstands that could be as tall as four feet high.

Glass lamps usually appeared in the form of kandelai , conical containers suspended from the ceiling or placed in stands made of wood or metal. Such devices could be multiplied to create elaborate polykandela , chandeliers capable of suspending numerous lamps for lighting large spaces. The collection of the Penn Museum includes several polykandela discovered during the course of the excavations of the houses on the Lower North Terrace, including a bronze disc (23.6 cm diameter) with six apertures for holding glass lamps, none of which survive. Three chains connect the disc to a hook for hanging. Another example found nearby has a more elaborate shape, with six round holes to support glass lamps. Although polykandela were typically found in churches and palaces—vast spaces with substantial endowments to pay for costly illumination—these examples were unearthed in an area of Beth Shean dominated by domestic structures, suggesting that such objects were used not only in institutional spaces but also within the homes of prosperous citizens.

While lamps made of metal and glass may have appeared with some regularity among certain echelons of society, the overwhelming majority of lamps in use between the 4th and 8th centuries were mold-made clay lamps. Two-part molded lamps originated during the Hellenistic period and continued to be the most prevalent form for more than a millennium afterward. The technique involves pushing wet clay into a pair of open molds made of plaster, clay, or stone. When partially dry, the shrinkage of the clay allowed for easy removal from the molds. Clay slip was used to fasten the two sides together before firing. Mass production of molded clay lamps began during the Roman Period in the 2nd century BCE, quickly spreading throughout the empire.

Molded lamps could take many forms, but most share certain features, including a reservoir for oil, at least one filling hole, a protruding nozzle with an opening for a wick, and some kind of handle. The upper part of a lamp, particularly the area around the filling hole, often served as a site for decoration. During the early centuries of the Byzantine period, lamps existed in a variety of shapes and displayed diverse imagery, including geometrical and zoomorphic patterns, as well as Christian, Jewish, and pagan motifs.

The numerous Byzantine lamps found at Beth Shean — most produced in nearby workshops — reveal the range of Palestinian lamp production between the late Roman period and the Arab conquest of Palestine. One of the earliest Byzantine lamps in the Museum’s collection is an unpublished orange clay lamp (a) with a round body and handle, decorated with two rows of darts around the filling hole and a pair of scrolls flanking the nozzle. Such lamps, common in Palestine during the 3rd and 4th centuries CE, resemble Roman types produced during the preceding centuries in workshops throughout the eastern Mediterranean and northern Africa. The irregular filling hole is likely the result of intentional breakage after firing, a common feature for lamps of this type.

Other lamps reflect a more localized tradition, including a so-called Beit Natif lamp (b), named for its resemblance to numerous lamps found during the excavation of two cisterns at Beit Natif in southern Judaea. Likely produced during the 5th or 6th century CE, the unpublished lamp is slipper-shaped and decorated with a vine and grape motif. Although it is tempting to interpret the grape clusters as Christian symbols, the motif had a broad appeal. Interestingly, the lamp displays no trace of burning around the wick hole, an indication that the lamp was never illuminated. Found in the north cemetery, the lamp may have been employed in a funerary context, a common practice among various communities during this period. Another rare variation of the Beit Natif lamp (c) has a round body with a square nozzle and a knob handle. Its sparce decoration consists of raised dots, dots within circles, and a stylized tree or branch motif. The lamp is similarly unpublished and also comes from the cemetery.

The grapevine motif recurs on numerous lamps in the Museum’s collection, including one example in which the looping vines serve as frames for depictions of deer and a rosette — possibly to be read as a Christogram (d). This type of lamp, with its ovoid shape, pointy nozzle, and knob handle, is particular to northern Palestine and can be dated to the years surrounding the Arab conquest of the mid-7th century. In fact, many of the terracotta lamps from Beth Shean date to the very end of the Byzantine period. Another unpublished example is of the so-called Samaritan type (e), with elaborate decoration of raised parallel lines and compartmentalized geometric patterns covering its upper surface. This type of lamp continued to be used into the early Islamic period.

It was during this late period that the use of clay lamps began to decline. Despite their popularity during earlier centuries, molded clay oil lamps practically disappeared after the 7th or 8th century. Citing the dearth of lamps in the archaeological record in the centuries following the Arab conquests, Cyril Mango suggests that the rising cost of oil would have made lamps prohibitively expensive for all but the wealthiest citizens, who would have owned metal or glass lamps. Mango notes that if candles were also too expensive for the common citizen, then “it would follow that a great many people in medieval Byzantium went to bed as soon as it got dark.”

For Further Reading

Hadad, S. The Oil Lamps from the Hebrew University Excavations at Bet Shean, Qedem 4. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology at theHebrew University of Jerusalem, 2002.

Rosenthal, R., and R. Sivan. Ancient Lamps in the Schloessinger Collection, Qedem 8. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1978.