“Here is to be seen those rare Curiosities that no City in the world can afford the like.” Thus Francis Mortoft, like so many other travelers before and since, paid tribute to the Roman ruins in 1659. These ruined temples, palaces, basilicas, and baths, these arches of triumph and “winding pillars,” with their statues of gods and emperors, sarcophagi and mural paintings, more than any other monuments of Europe engrossed men’s minds and led them to literary and artistic expression.

“Is it but marble that I see?” asked Mrs. Millar in Rome in 1771. The answer of course was no, for she saw the stream of history brought to life in Roman moonlight amongst “the stupendous monuments of past ages,” as Petrarch had felt it in the fourteenth century and Montaigne in 1580. With all their connotations, the Ruins of Rome were a constant invitation to moralists to contrast the grandeur of the illustrious past with the decay of the miserable present and to poets they gave a dark but noble theme that flowered in Romanticism. These ruins offered also an endless invitation to admire, to study, to record, and to collect, which has mightily enriched our civilization. From their presence have come the traditions of private and public collecting, the beginnings of archaeology and museology, of travel for the enlightenment of the mind and the formation of taste. They have on a number of occasions inspired a classical style that has affected every aspect of design and in the eighteenth century they brought forth the first original American contributions to academic art. The Ruins of Rome have also called into being a host of drawings, prints and paintings made to record their enduring splendor, many of which are important works of art.

The history of our concept of the Ruins of Rome begins in the twelfth century, when Cardinal Giordano Orsini formed his collection of antique marbles and thereby launched the tradition of the noble collector of ancient art which culminated in the eighteenth century. The original text of the first guide to the ruins of Rome, the Mirabilia Urbis Romae, although written for pilgrims to the Christian shrines, expressed respect for pagan architecture.

It was not however until the third quarter of the fifteenth century that the modern concept of the city of Rome as a great museum developed. By this time the classical Renaissance of the Florentine humanists was in full swing. The ruins had been measured by Brunelleschi with a view to bestowing something of their grandeur upon buildings of his time; in Florence ruins had become a fashionable subject for the background of religious paintings; and in Rome itself Sixtus IV in 1471 had created in the Capitoline Palace adjacent to the Forum the first museum of classical antiquities. The Belvedere Museum with its spectacular statues was opened in the Vatican in 1506 and others were established in the gardens of the Cardinals Cesi, Este, and Della Valle.

Here the first travelers who wrote down their impressions of Rome mingled with scholars who had come to study and artists who had come to sketch the statues and decorative reliefs. Some of the finest of these mid-sixteenth century Italian drawings are now in collections in this country, including a sheet of Della Valle marbles attributed to Giorgio Vasari and sketches of sarcophagi which appear to be the work of Girolamo de Carpi. There is also Federico Zuccaro’s cartoon for a palace fresco, showing his brother Taddeo sketching the Laocoon in the Belvedere with a glimpse of the Vatican Loggie where Raphael had painted his grotteschi decorations in imitation of the antique arabesques found in the ruins of the Golden House of Nero during the excavations of the early Renaissance.

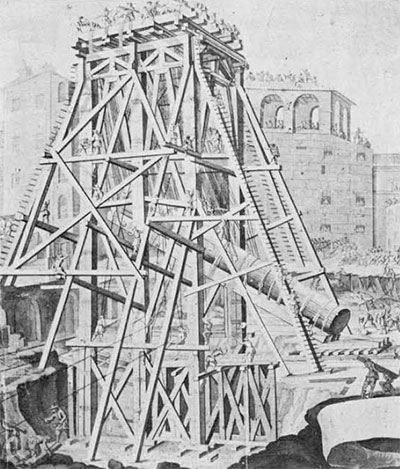

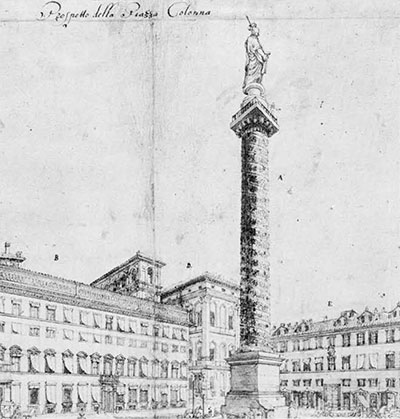

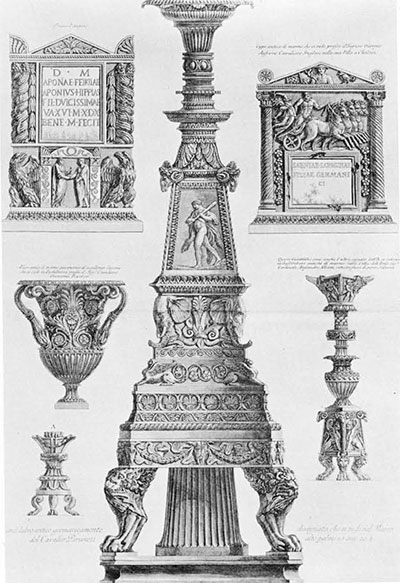

Rome was now for the first time since antiquity an international center of art and much of this note taking on the ruins was done by foreign artists for the purpose of publication. In 1544 appeared the first engravings of ancient objects published by the Burgundian Antoine Lafrerie. The Roman drawings of two other Frenchmen, Jean-Jacques Boissard and Etienne Duperac were later issued in the form of topographical albums including pictorial maps of the Ruins of Rome. In 1576 was published the first monograph on one of these monuments, the illustrated history of the column of Trajan by the Spaniard Alfonso Chacon, which was to be followed by a long series of sumptuous volumes devoted to this, the Colosseum, the triumphal arches, and the catacombs.

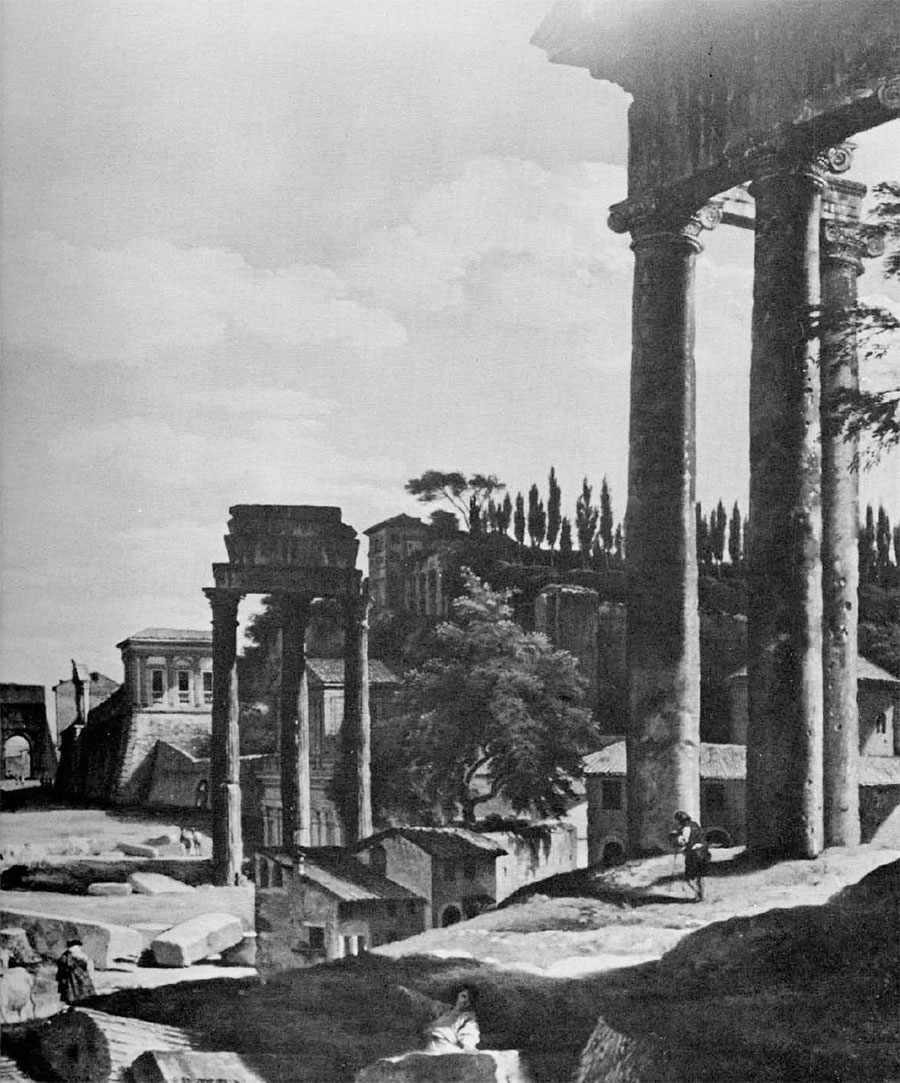

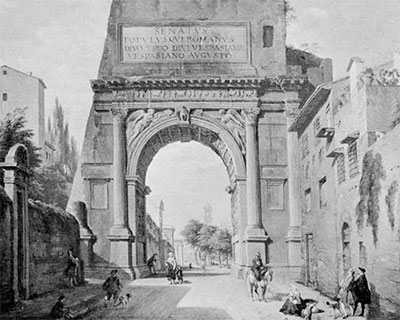

Artists in the sixteenth century looked on the Ruins of Rome with respect and awe, making precise and often scholarly sketches that frequently have the value of showing minutely some lost work of art or ruined building since further defaced or, like the Septizonium, totally destroyed. The artists of the seventeenth century treated the Roman ruins with more familiarity. They tended to see them not so much as isolated monuments of the ancient past as integral parts of a landscape which they composed according to formulas that soon became academic. The concept of landscape as a distinct kind of painting, a genre in itself, was a new one, created largely in Rome in the early seventeenth century and in the presence of the ruins. The latter frequently imposed upon these pictures a silent, meditative quality that reflects what one eighteenth century traveler termed the “severe majesty that seems to preside as the genius of the place.” Classical landscapes they were called not only for the ruins and their spirit but also because of the persons in quasi antique dress that often figured in them. The new genre was as much the creation of expatriate Frenchmen, Dutchmen, and Germans as it was of native Italians. Indeed, as the century progressed foreigners dominated this kind of painting.

Nicholas Poussin, who came from Paris to Rome in 1624 and died there in 1665, is recognized as the supreme master of this type of landscape, for to it he brought the spirit of a classical philosopher and a sense of monumental plastic form. Many in the past, however, have preferred the work of his brother-in-law Gaspard Dughet Poussin, who reduced the classical formula to a picturesque routine in his pleasant, easily understood landscapes filled with recognizable ruins and statues of the genii loci. This was a very superior kind of tourist painting and the travelers including eighteenth century Americans revered it. “The pale green Gaspard Poussins,” wrote Mrs. Piozzi in 1784, “so valuable, so curious…”; and when in 1801 an anonymous “Native of Pennsylvania” visited the studio of the Roman engraver Volpato it is not surprising that the artist was found to be making a print of “a fine composition by Gaspard Poussin.”

“Nature and Claude” continued Mrs. Piozzi, “content my fancy,” for she found in the classical landscapes of Claude Lorrain, the second great French painter who in the seventeenth century made his career among the Ruins of Rome, a freer and more lyric note. Especially is this true of Claude’s drawings of column-strewn landscapes outside Rome and the brilliant etchings based upon them. This essentially romantic approach, conventionalized by the Franco-Dutch painter Jan Asselyn, Bartolomaeus Breenbergh, and others, became by the close of the century a rival to the Poussin manner among the Netherlands painters and draftsmen who lived and worked in Via Margutta. Its spirit survived in the eighteenth century in small, poetic landscapes of the Englishman Richard Wilson and in some of the work of the great French landscapists Claude-Joseph Vernet and Hubert Robert.

Apart from these classicizing circles another group of Low Country artists depicted the Forum and other parts of ancient Rome with almost photographic realism and reportorial exactness of detail, using as their model Flemish background scenes of the fifteenth century. Nothing can better illustrate this approach than the brilliantly lighted, meticulously rendered drawings m ad ein the heart of Rome by Lieven Cruyl, a priest from Ghent with notions of architecture. Precisely dated, frequently by month, between 1664 and 1666, Cruyl’s views convey a picture of a busy living city filled with ruins quite different from the staged effects of the classicizing painters. Such drawings as these lead directly to the tempera landscapes of the Dutchman Gaspar van Wittel, called in Italian Vanvitelli and Gaspare dagli Occhiali because of the spectacles he wore when working. This transportation of names is not without significance, for it symbolizes the artist’s hybrid style. As van Wittel he kept his Dutch respect for realism and deference to detail; but as Vanvitelli he composed with a measure of Italian grace and brio the animated figures of his small urban paintings and the sweeping foliage of his drawings of the landscape of the Tiber. In his work the baroque style had its first effective contact with the Ruins of Rome.

Vanvitelli, who lived until 1736, to a large extent created the sprightly veduta style of topographical painting which in the eighteenth century took Italy and especially Rome by storm, bringing Italian artists to vie with foreigners in painting views. In this they were influenced, without doubt, by the stream of wealthy travelers, making what Richard Lassel in 1670 had dubbed “the Grand Tour,” who were eager to acquire souvenirs of what they had seen. They were also encouraged by the spectacular success of the Cavaliere Giovanni Paolo Panini, who improved the genre of Vanvitelli and made it an ideal vehicle for the portrayal of ruins.

Born in northern Italy, the home of dramatic baroque architecture and stage design, Panini developed in the 1750’s the formula of the veduta with ruins. This he did by using larger canvases painted in fresh, clear colors and handsome figures of spectators better drawn than those of Vanvitelli, frequently grouping in arbitrary fashion the most famous ruins of Rome, as the Frenchmen Charles-Michel Challes and Charles-Louis Clerisseau were also to do. Through Panini’s drawings, which project the setting of a baroque ballet, recurs the heroic theme of a stately ruined colonnade encasing the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, “the noblest statue in the world,” thus repeating the theme of a distinguished German drypoint of 1515 included in the Lessing J. Rosenwald collection. Around this kind of work developed the taste for fantastic ruins, nourished by painters throughout Europe.

We see them in the greater attention now paid to classical costume and physiognomy in painting and sculpture and in the tendency to restore, to “bring to life” the Roman ruins. Thus Benjamin West of Philadelphia after a few years study in Rome will paint in London in 1765 a classical scene as though it were an antique bas-relief and people the background with intact Roman temples as Nicolas and Gaspard Poussin had occasionally done in the seventeenth century. Hubert Robert’s sanguine drawings mingle actual Roman ruins with well preserved classical halls and cupolas that reflect the growing preoccupation with these majestic themes among the architects of the French Academy in Rome–designs which were subsequently published in Paris and London.

Meanwhile, with the discovery of the buried cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii and the formation of the Albani and other great Roman collections of the eighteenth century, the study and publication of antiquities enormously increased. From 1760 onward Rome, Paris, and London became the three centers of a rapidly developing classical taste in architecture and the decorative arts, which produced the great pattern books of Piranesi, Delafosse, and Robert Adam and later, as archaeological exactitude increased, the plates of Sheraton, Tatham, Roccheggiani, Percier and Fontaine, and Thomas Hope. By 1800 the influence of these publications on the decoration of walls, mantels, furniture, and fabrics was so thorough that there was scarcely a useful or ornamental object which did not in some telling fashion reflect the image of the Ruins of Rome. A similar manifestation of neoclassicism had occurred in the sixteenth century but the revival of the late eighteenth century was a hundred times more thorough.

Another impact of the Ruins of Rome on eighteenth century art occurred in the field of portraiture. Already in 1670 Lassel had recommended that all travelers to Rome have “a full draught…of profane Antiquities” and this suggestion eventually led to the taking of courses with an antiquarian, which generally lasted about six weeks, three hours a day. “I have viewed with enthusiasm classical sites…,” wrote James Boswell, as a student of antiquities in Rome in 1765, “I have made a thorough study of architecture, statues and painting; and I believe I have acquired taste to a certain degree.” As though to celebrate these tourist activities, Panini painted a decade earlier his Gallery of Roma Antica, in which travelers are seen studying a large collection of vedute of ruins.

In similar spirit the Roman portraitist Pompeo Batoni and his foreign followers in Rome posed their sitters in the midst of ruins or works of ancient art. Thus the French ambassador Cardinal de Bernis, the premier host of Rome in the second half of the eighteenth century, was painted by the German classicist Anton Rafael Mengs, in the presence of the Dioscori and the Apollo Belvedere, that best loved work of art which Tobias Smollett in Rome in 1765 called “the most beautiful statue that ever was formed.” The English painter Nathaniel Dance chose a setting of ruins and sculpture for his conversation piece of about 1762, showing a group of young British Grand Tourists, one of whom, the son of the architect Sir Thomas Robinson, holds an architectural drawing like those in the Roman sketchbooks of Robert Adam and Joseph Wright of Derby. John Singleton Copley of Boston in 1775 showed Ralph Izard of Charleston, South Carolina, American Minister to Tuscany, and his wife sitting in state before the Colosseum beside a well known antique statue and a Grecian vase.

Some of those who enjoyed what in the sixteenth century had been termed the “English Romayne Lyfe” in the inns around Piazza di Spagna, where British bacon and puddings were always available, returned home with marbles and other antiquities, others with replicas, for as Samuel Sharp reported in 1765, “it is of late become a fashion amongst our Nobility to bespeak copies of statues and pictures from their countrymen,” the “good, sober, industrious” English art students resident in Rome.

The English also brought back the new books on the Ruins of Rome by such illustrious antiquarians as Francesco Ficoroni, the chief cicerone of the foreign tourists (“vieux, sourd, parleur impitoyable et fatigant”), Giovanni Gaetano Bottari, the Vatican librarian, and Ennio Quirino Visconti, the first curator of the Louvre. They purchased the panoramas of Vasi and Piranesi and for them Englishmen like Stephens, Sandby, John Smith, and Domenico Montagu published collections of engraved views. About 1798 appeared Merigot’s Views and Ruins of Rome, in the peculiarly British form of a handsome folio of aquatints.

By this time, Napoleon had invaded Italy and successfully demanded for Paris the masterpieces of Roman museums, dispersing these treasures and interrupting for a time the tradition of three centuries of contemplating and recording the Ruins of Rome, “Urbis Eternae Vestigia.” The Forum, forsaken by tourists, the Capitol, Pantheon, and Colisseum, relaxed as it were before the greater onslaughts of the nineteenth century, must in that moment especially have deserved the noble words of Charles de Brosse in 1739, “Tout y est simple, naturel, auguste, et, par consequent, sublime!”