“The Eckley B. Coxe, Jr. Expedition of the University of Pennsylvania did solid but unsensational work in Nubia and then moved north to Dendereh and Memphis.” (John Wilson, Signs and Wonders upon Pharaoh. A History of American Egyptology, 151).

This quotation, the only substantial reference to the University Museum’s Egyptologists program in the best and most authoritative history of American Egyptology so far written, brings out a curious paradox. Over the years the Museum’s Egyptian Section has greatly enlarged knowledge and understanding of ancient Egypt, but this fact has not had the impact in either the scholarly or the public world that it should have. This is not the fault of careful and generous historians like John Wilson, but is due to a disservice the Museum has done itself. It has always employed well qualified Egyptologists who consistently chose sites of major importance, sites yielding masses of new and valuable information carefully recorded and documented. This represents however only one aspect of the work of an archaeological or epigraphic expedition. Without subsequent research, synthesis and publication or, in plain terms, the writing of scientific monographs and papers, and popular books and articles, this laboriously and expensively gained knowledge is of little value to the scholarly world or the interested public in general. And, in fact, of the eight Egyptian field projects directly sponsored by the Museum between 1906 and 1956 four of the most important have either been only very partially published or hardly published at all.

We must not over-exaggerate the Museum’s Egyptologists achievements. Compared to those of other United States institutions, it did not enjoy the very substantial financial resources which supported the extensive Egyptian field projects of New York’s Metropolitan Museum from 1910 to 1936 or which have maintained the epigraphic expedition of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago in the field since 1924. Nor was the University Museum associated over a long period with a single brilliant and productive archeologist who was virtually always in the field, as the Boston Museum of Fine Arts was with George Reisner from 1906 to 1942. Nevertheless, in comparison with the work of these institutions that of the University Museum is consistently underestimated; its contributions were major and important to an unappreciated degree and this is largely because a much larger proportion of the work of the other institutions referred to has been published. At the moment therefore we can describe the University Museum as a major contributor to our knowledge of ancient Egypt only in a qualified sense, anticipating the full publication of its rich stores of important Egyptological data.

As we try to demonstrate what it was that was important about the material recovered by the Museum in Egypt we must take into account the fact that Egyptology has been a vigorous and changing discipline. Any good piece of work done in the past will provide data valuable enough, if sufficiently well recorded, to contribute to our understanding of what we think of today as the most important aspects of Egyptian history and culture. But the work of each of our predecessors must also always be evaluated with reference to the scholarly standards and preoccupations of his particular generation of Egyptologists. Research priorities and values change significantly over the years and what seemed legitimate in the circumstances existing at one time might no longer be acceptable in the changed circumstances of a later period of study and research.

Egyptology is a young discipline, which in a real sense came into existence in September 1822 when the young Jean Francois Champollion burst into his brother’s office in Paris, threw a bundle of papers on the desk, cried “I have got it!” and promptly collapsed into an exhausted stupor for five days. After months of intensive intellectual effort, often following false leads to their baffling or discouraging conclusions, Champollion had suddenly fully grasped the nature of the hitherto largely untranslatable hieroglyphic script.

Others had come close to the solution, but in Champollion’s work it crystalized out and his peers were for the most part rapidly convinced of the accuracy of his results. In that instant in 1822 the inscribed monuments of ancient Egypt, unintelligible for over a millennium since the last hieroglyphic and cursive texts were written in the 5th century A.D., became accessible and its extraordinary history and culture began to emerge as it had been recorded at first hand by the Egyptians themselves. Inevitably the best Egyptologists of the next seventy years concentrated upon the texts rather than upon the archaeology of this richly literate culture. Its basic chronology and history—the essential framework for future research—were outlined and increasingly sophisticated standards of epigraphic recording and philological analysis and instruction developed.

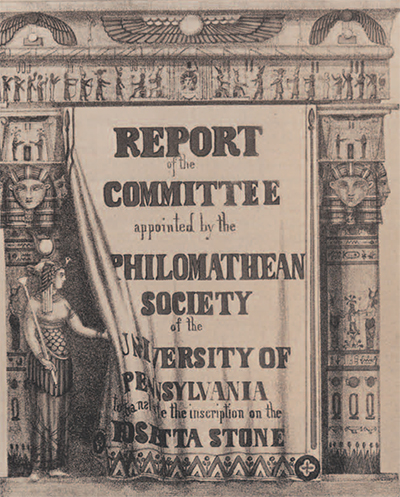

Surprisingly early in the period the University of Pennsylvania emerges into the story of Egyptology with one of the earliest Egyptological publications in the United States, In 1858, thirty-six years after Champollion’s momentous discovery, three graduate students who were members of the Philomathean Society of the University published a translation of the Greek and ancient Egyptian texts of the Rosetta Stone. This famous bilingual decree of Ptolemy V in 196 B.C. had been important for the decipherment of the hieroglyphs and several translations existed already.

Nevertheless, this was a “new and independent” one and, gaily decorated in lithography by one of the authors, it proved to be a best-seller and was reprinted in 1859. The translation was a creditable one and should always be remembered in our local annals for the delightful premise upon which it was based, namely “that nothing possible to man ought to trouble a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and of the Philomathean Society.”

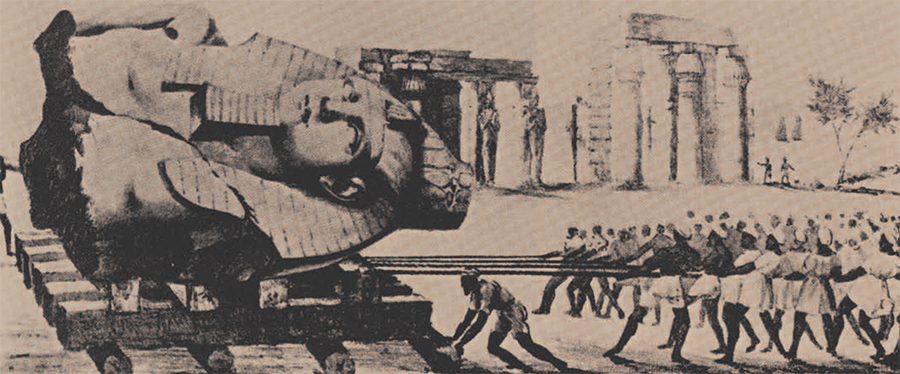

During the first four decades (1822-1860) of productive philological research the archaeological picture in Egypt was bleak. With a few exceptions, scholars in general during that period did not appreciate the historical and cultural significance of the archaeological data on any culture, and Egyptian sites were ransacked for additional texts and for art works and the more exotic artifacts such as mummy-cases and canopic jars. The European interest in Egyptian art and ‘curiosities’ which had been strong since the 16th and 17th centuries was now much enhanced by the decipherment of the hieroglyphs. Also, Egypt itself was much more accessible to foreigners in the 19th century than was the case earlier. There ensued an orgy of destructive plundering in which on occasion crowbars, battering rams and gunpowder were used to accelerate recovery.

The Egyptian government of the Khedive Said took steps to stabilize this chaotic situation and in 1858 appointed Auguste Mariette as Conservator of Egyptian Monuments, a position later expanded into the Office of Director General of the Antiquities Service, or Antiquities Organisation as it is known today. For the first time there was a government agency charged with the protection of Egypt’s ancient sites and monuments and Mariette made the most of the opportunity. A larger than life personality, Mariette was vigorous, combative and aloof, although he diplomatically maintained good relations with the Khedive,the ruler of Egypt. In the context of the times his achievements far outweighed his defects. It is true that he engaged in excavations at several sites at the same time and concentrated upon the recovery of inscriptions and art works with little concern for context, but he was an able, professional Egyptologist whose monopoly of major excavations in Egypt, by virtue of his office, saved many sites from the archaeological bandits who had preceded him. At Mariette’s urging legislation protecting Egyptian antiquities was approved —amongst the world’s earliest such legislation. It is due to this legislation that the Antiquities Organisation has the legal obligation to expropriate at the lowest reasonable price land upon which significant ancient remains have been found. Mariette also established the nucleus of a national museum, which created a mechanism inhibiting the flow of antiquities out of the country. Later the museum became the repository for thousands of art works and artifacts recovered by excavators working under the more permissive regimes of Marietta’s successors, Maspero and later Directors-General. The later history of the Antiquities Organisation and Cairo Museum is given elsewhere in this magazine. (See p. 45.)

The principles and methods of well-controlled, carefully recorded archeaological excavation were introduced into Egypt during the 1880’s and ’90’s, quite soon after they had begun to be established in England and Europe. The two men mainly responsible were an Englishman, Flinders Petrie and an American, George Reisner. Many of the excavators active in Egypt well into the 1930’s had been trained by Petrie or Reisner, but never by both! Throughout their long careers the two men remained respectfully remote from each other, their implicit professional rivalry being accentuated by marked differences in personality and techniques of excavation and analysis. Both were combative and rather autocratic, although Reisner mellowed over the years and Petrie always had an unexpected streak of impish humor. In his 70th year, laden with academic honors and one of the ‘grand old men’ of Egyptology, Petrie chose to rest, in his memoirs that as a young man surveying the pyramids at Giza he found “for outside work in the hot weather, vest and pants [underwear] were suitable, and if pink they kept the tourist at bay, as the creature seemed to him too queer for inspection!”

The advent of scientific archaeology in Egypt brings us to the beginning of the story of Egyptology at the University Museum, for the Museum was closely associated with this innovation. For many years after 1890 it was one of the main sponsors of Petrie and others of his “school”: and the first Egyptologist it engaged [in 1906) was David Randall Maclver, who had worked in the field with Petrie, and who trained Charles Leonard Woolley, subsequently to become famous for his discovery of the ‘Royal Tombs’ at Ur on behalf of the University and the British Museums! Finally, Clarence Fisher, Egyptian curator and field director from 1914 to 1925, had spent several years working with Reisner before his appointment to the Museum, as had his successor, Alan Rowe.