For almost 80 years, the 49-minute film Matto Grosso: The Great Brazilian Wilderness lay in the Penn Museum Archives, waiting for the day when it would be rediscovered and identified as the first “sync sound” documentary film ever created. This film—part adventure movie and part documentary—was restored and digitized by archivists in 2010.

The original idea for the film came from a group of businessmen and adventurers. E.R. Johnson, co-founder of The Victor Talking Machine Company (later part of RCA), and his son Fenimore Johnson, an engineering graduate from the University of Pennsylvania, were both members of the Penn Museum Board. They were also very interested in the developing field of film technology. In 1930, Fenimore was asked by his friend and former classmate, John S. Clarke, to fund a zoological and ethnographic expedition that would be filmed in the Mato Grosso plateau of western Brazil. Captain Vladimir Perfilieff, a Russian-born artist and adventurer connected with the Explorer’s Club in New York, would be part of the team traveling to South America. According to one account, the budget for the Depression-era expedition was quite large at $100,000.

In a March 6, 1931, interview in The New York Times, Fenimore Johnson suggested that the group would be recording a disappearing culture as well as making film history: “These frontiers are rapidly disappearing. This is one of the last, for it won’t be long before the Brazilians will push in there, and the last of the native languages and customs will start disappearing. Much valuable knowledge of peoples, animal and plant life will thus be lost, as far as the world’s history is concerned. It is our intention to preserve as much of this as possible; we hope to be the first expedition to bring back actual sound recording films taken in the jungle.”

The Expedition

The expedition set off from New York harbor on Western World of the Munson Line on December 26, 1930, with a pack of hounds, a large amount of gear, and a Hollywood film crew. They arrived in Montevideo, Uruguay, and proceeded by airplane and on the steamer Paraguay to Brazil, arriving January 30, 1931, and then on to a ranch in Descalvados to set up camp. After receiving permission to work in the Mato Grosso region, they organized the transport of their equipment and provisions overland on oxcarts, followed by travel on nearly 2,300 miles of winding rivers deep into the interior of the Amazon in a boat they nicknamed El Wunco.

Many of the expedition party were primarily interested in the hunting aspect of the trip, which is reflected in large segments of the film. The competing purposes of the filmmakers created a tension in the film’s editing, resulting in a film that wavered between adventure and science, between Hollywood and academia. Perfilieff’s plan, to make an adventure sequence of Sasha Siemel spearing a jaguar in midair, fell apart when the animals did not cooperate in the corral that was constructed for the film. More on these misadventures is described in previous Expedition articles by Eleanor M. King (1993) and Alessandro Pezzati (2002).

The Production

To add substance and legitimacy to the project, the University of Pennsylvania and the Penn Museum were asked by Fenimore Johnson and others to provide an ethnographer for the expedition, in addition to the naturalists from the Academy of Natural Sciences already scheduled for the trip. When the expedition team and film crew arrived in Mato Grosso, the ethnographer Vincenzo Petrullo quickly discovered that the São Lourenço Bororo were not as remote or un-contacted as he had hoped. Consequently, he pursued much of his own field work farther up-river with the Yawalapiti and in other more remote Xingu villages of the upper Xingu River Valley.

Had a script been written in advance, the film might have become a complete feature film akin to Robert Flaherty’s Tabu (1931, written by F.W. Murnau), with a traditional narrative story line. As it turned out, there was less planning and more improvisation in the production of Matto Grosso, although some staging is quite apparent. This may be due to the recent experience of cinematographer Floyd Crosby’s filming of Tabu under Flaherty, who is known to have staged many scenes in his documentary films, beginning with the silent Nanook of the North (1922).

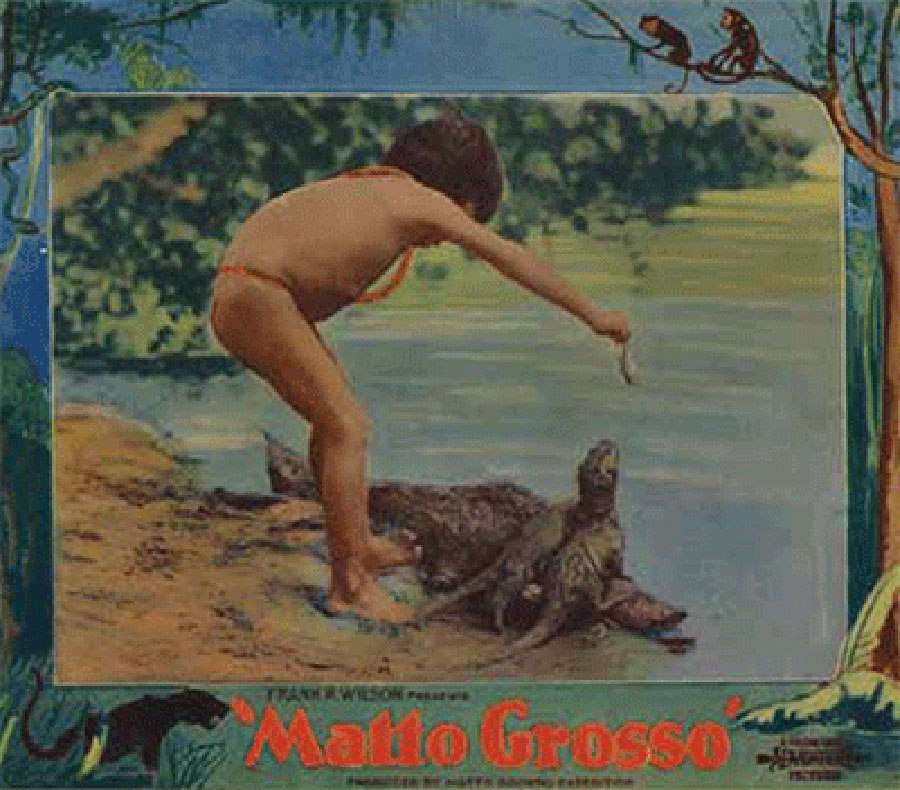

The lead character in Matto Grosso is a Florida “cracker” guide, “Uncle” George Rawls, his real name, who was hired to play an explorer, and appears throughout as a kindly man who makes friends with a Bororo boy and sets up a temporary trading post. A 1931 New York Times review at the time mentions the “staged scenes,” although the filmmakers implied that this was a first contact situation—a popular narrative trope. This was inconsistent with the film, since the character of the “Chief” speaks Portuguese fluently in several scenes. Despite its flaws, Matto Grosso has become an archival record for these source communities, both as personal history and as primary source material.

A Hollywood Crew

The cinematographer Floyd Crosby was the best-known member of the crew. He was fresh from the photography of the film Tabu, for which he later won an Academy Award for Best Cinematography. He also brought his new bride, Aliph Van Cortland Whitehead Crosby (the singer David Crosby’s future mother), who acted as the unofficial pharmacist on this unusual and unplanned honeymoon.

Crosby was dismissive of the pre-production planning of Matto Grosso, as well as the expertise of its ad-hoc directors. Because of his experience with Flaherty, he had a better idea of how to construct a narrative than other members of the expedition. He took charge of directing the project after then-director John Clarke and several crew members were injured or became ill and decamped.

Author Nick Pasquariello’s oral history interview with Floyd Crosby contains this reference to the production: “We were thousands of miles from everything, everything we needed we had to take with us, all the camera equipment, the film, we had no lighting equipment as it was all exteriors; we took two refrigerators there, we took a little electric generating plant….” It is not known whether the film was developed in the field, but it is likely that the refrigerators kept the 35mm nitrate film stock cool before and after exposure.

The dauntless Hollywood film crew worked under hot and humid conditions for months on end, with the weather equally tough on the gear. Soundman Ainslee Davis was praised by Fenimore Johnson for having nursed one remaining microphone through encroaching mold and mildew to the bitter end of the trip, all of the others having succumbed to moisture damage. The ethnographer Vincenzo Petrullo wrote that the microphones in fact had begun to be taken over by mold in Descalvados, before they were even used.

The Technology Behind The Film

Fenimore Johnson’s engineering background and his connection to RCA may account for his enthusiasm for gathering sync sound in the field, quite early in the history of sound for film. To provide historic context, the RCA Photophone variable area sound-on-film system was developed in 1925 by Bell Laboratories and released in 1929. As of 1930, when the expedition departed from New York harbor, fewer than 30 RCA Photophone system films had been made in a controlled interior studio environment, mostly at RKO Studios in Hollywood.

For Matto Grosso, Floyd Crosby used an experimental Mitchell camera with a mounted sound head for single system film sound recording, much as a video/news crew works with today. This camera set-up came with an amplifier panel, a direct current battery for the camera, and a sound attachment mounted on the camera just below the magazine, using the same drive mechanism. According to C.R. Hanna, the system, at 70 pounds, was then considered “a compact camera, adaptable for news pictures, (and) uses an especially robust galvanometer with uniform response up to 5,500 cycles for variable area recording.” Vincenzo Petrullo mentions in his manuscript, “We were well equipped…with the most expensive cameras and an expert staff of cameramen. We felt the pride of pioneers in that we were the first group to take to the field a sound-track-on-film recording apparatus, a bulky and expensive affair which induced a feeling of awe in everyone but the sound engineer who spent most of his time cursing the designers and makers. It was an experimental set, the second ever built…”

Matto Grosso In 1931 And 1941

The film opened to mixed reviews in New York City in December 1931, and was screened with West of Singapore, a romance set in the Pacific. Johnson later had several 16mm prints made for screenings at the Penn Museum. The last remaining Museum copy was recently restored and preserved under a grant from the National Film Preservation Foundation. As with other films produced by the Museum, the film footage of Matto Grosso was repurposed and re-edited several times. Two later films were reassembled by producer and filmmaker Ted Nemeth from the footage shot in Brazil in 1930, and narrated by Lowell Thomas: Primitive Peoples of Matto Grosso: The Bororo (1941) and Primitive Peoples of Matto Grosso: The Xingu (1941). Today we cringe at the attribute “primitive” as a descriptive; similarly, the narrative of these films reflects the cultural prejudices of the times.

In a peculiar twist, “Uni” (1941), Vincenzo Petrullo’s unpublished manuscript on the expedition, reveals a strangely ethnocentric mindset about the Bororo, a direct contradiction to the teaching of his mentors. None of his former professor Frank Speck’s teaching on equality and cultural relativism is reflected in this work. As recounted by Petrullo, it is rather the non-academic Fenimore Johnson who looks better to history, as in: “How do we measure the fitness of a race? Especially when we devise our own scales.”

We recently learned, reading Vincenzo Petrullo’s papers, that the scripts for the later films were likely drafted later by Petrullo. The three films provide a striking contrast in how the perspectives of the writer and editor can change the depiction/perception of the peoples filmed. Although much of the same footage is used in the earlier and later Bororo films, the narration gives a completely different tone and set of meanings.

Note this sequence in the narration from the earlier film: “Much of their complicated symbolism was beyond our understanding…A profound religious significance lay behind the ceremony. Among them we began to realize outward forms and gestures played a more important role than simple action…Across the village another group performed a second and related dance…not until this was done was the slightest effort made toward any actual preparations for a hunt.”

Contrast this with a narration sequence from Primitive People of Matto Grosso: The Bororo, written by Petrullo: “Formerly the arrival of strangers would have been received with suspicion and the men would have seized their bows and arrows but in recent years the Bororo have been pacified by the Brazilian government. The Bororo are a large heavily built people with a strong Mongoloid appearance, which is emphasized by their custom of shaving of the eyebrows and the temples. Formerly they went naked, but many of them now possess scraps of filthy cloth which have been obtained in trade for some bow or arrow.” This lack of a deeper understanding of the culture and context, and the blunt, demeaning description of the Bororo would be offensive to all of us today.

The age of large, individually sponsored expeditions ended many years ago. Filmmakers from international communities now produce their own documentaries, providing essential indigenous perspectives to their work. As archivists, we have arrived at a thrilling time in which we can sort through existing collections and bring out forgotten historic materials, and make them accessible as never before.

Sound Recording In Documentary Films

In the mid-1920s competing companies worked diligently to improve their film sound recording systems in an attempt to corner the production and distribution markets. It has been theorized that Sam Warner’s urgent and dogged pursuit of sync sound film technology (the Vitaphone system) before the crash cost him his health, but made the technology financially possible. General development of film sound technology slowed dramatically after the 1929 stock market crash. The industry did not begin work on the next major technology, magnetic recording, until the end of World War II. In the history of documentary films, Matto Grosso was to be in the vanguard for sound. Zoran Sinobad at the Library of Congress Motion Picture Division writes that Matto Grosso was the first sound documentary film to appear, followed by The Strange Case of Tom Mooney (1933) by Bryan Foy. After Matto Grosso, the next significant sound documentary films were from the British Documentary Film Movement of the mid-1930s, including Night Mail and Song of Ceylon, filmed non-synchronously.

For Further Reading

Hanna, C.R. “The Mitchell Recording Camera, Equipped Interchangeably for Variable Area and Variable Density Sound Recording.” SMPE 38 (1929): 312-317.

King, Eleanor M. “Fieldwork in Brazil: Petrullo’s Visit to the Yawalapiti.” Expedition 35.3 (1993): 34-43.

Pezzati, Alessandro, with Darien Sutton. “The Present Meets the Past: Edith and Sasha Siemel.” Expedition 51.3 (2009): 6-9.

“To Make Jungle Talkies.” The New York Times, November 20, 1930, p. 34.

For a longer version of this article and full bibliography, please visit www.penn.museum/sites/mattogrosso