“The closer you get to Benin City, the further away it is.” This Edo proverb speaks to the complexity of Nigeria’s Benin Kingdom, a living society whose history dates back over 900 years. At the Penn Museum, we hope our physical distance provides at least one vantage point for museum-goers to appreciate not only Benin’s world-renowned sculpture, but also its rich past and present through compelling objects and stories of remarkable individuals. Their rivalries, tensions, and quests for recognition provide the impetus for understanding and interpreting the art.

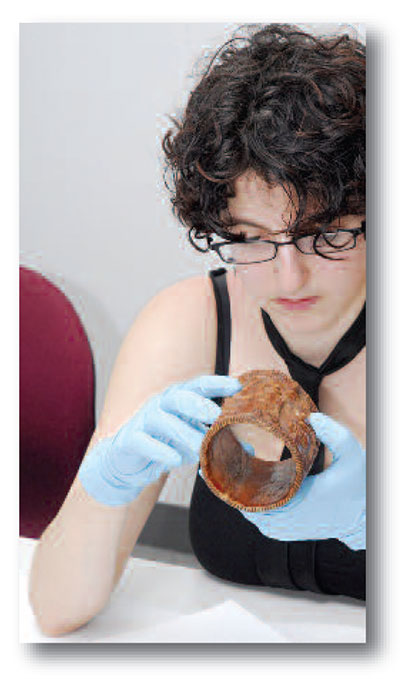

IYARE! Splendor and Tension in Benin’s Palace Theatre, running from November 8, 2008, through March 1, 2009, in the William B. Dietrich Gallery on the Museum’s second floor, displays nearly 100 objects from the 16th century AD to the present. As guest curator, I developed the idea of the exhibition, and then fleshed out some of its specifics with undergraduate and graduate students in the History of Art Department’s Halpern-Rogath Curatorial Seminar. After studying the history of museum practices, the students traveled to see four Benin displays in New York and Washington, DC. They analyzed those exhibitions, coming up with imaginative suggestions and caveats, many of which we incorporated in IYARE! The seminar’s participants handled storage pieces, debated how to address certain issues, and helped plan an in-depth website, also writing object entries for the companion catalogue. Subsequently, students in an Introduction to African Art class distributed an extensive questionnaire, further refining choices of featured objects, marketing strategies, and programming.

The Penn Museum’s Benin collection was the first in the Americas, and its holdings include many rare and unusual pieces. IYARE! supplements these objects with loans from institutions such as the Brooklyn Museum and the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African Art, and from selected collections.

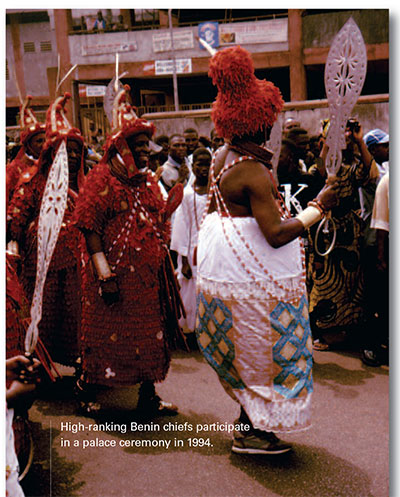

The exhibition examines the highly dramatic environment of Benin’s palace, the locus of political, religious, legal, and ritual activities. The seat of the monarch, or Oba, is usually abuzz with some of the kingdom’s more than 300 chiefs, as well as courtiers, royals, visitors, and citizens bearing gifts, news, or problems. Benin’s wealth and its rulers’ tastes have made the palace an artistic center. Royal guilds of casters, carvers, and leather and bead workers created an environment emphasizing the kingdom’s wealth and power, and reinforcing its hierarchy.

There is no literal theatre in the palace, but many of its ceremonies re-enact historic events in a ritualized format. Oba Esigie, a 16th century ruler, created the Ugie Oro festival. The monarch and chiefs carry short staffs representing a bird tapping its beak with a rod to recall an alarming event with a victorious conclusion. After an attempted Igala invasion, the Benin armies pushed their enemies back to their own territory across the Niger River. In his war camp, Esigie debated whether that success was sufficient. Should he return home with his battle-wearied troops, or cross the Niger for a final conquest? No die was cast, but a prophetic bird did fly through the camp. It had two cries—one advised continuing an enterprise, the other abandoning it. It called out the latter. Instead of obeying the bird’s advice, Esigie had it shot. The king went on to triumph, commemorating an event showing the Oba’s powers could trump fate.

IYARE! interprets objects such as the bird staff through a theatrical metaphor, dividing the exhibition into six groupings. The first, “Sets & Backdrops,” looks at the palace itself, and how its awe inspiring wealth—over 900 gleaming brass relief plaques once decorated its pillars—reinforced the impact of the Oba’s power.

The second section, “Players, Props & Costumes,” presents objects associated with those who move across the palace stage—the Oba, his chiefs, guild members with specialized duties ranging from ritual medicine to tending cows, the child pages, warriors, foreign visitors, and royal and chiefly wives. Their personal objects exemplify the kingdom’s sumptuary laws, whereby ivory, brass, and imported coral beads were the Oba’s privileges, awarded to chiefs according to their rank.

The third division, “Scripts,” looks at ceremonies and other events through video footage and related objects. Smaller everyday dramas feature as well. Being a notable in Benin is fraught with tension—those who rise to the top have always had rivals and detractors who hope to topple them.

In a break from the palace’s peak moments, the “Intermission” section considers the palace’s “off” times, when guilds produce brass, wood, ivory, and beaded objects, and courtiers spend leisure time playing music or board games.

Extending the theatrical metaphor, “Playing the Provinces” explores the ways Benin’s art colonized that of its neighbors. Ishan, Itsekiri, Owo and Ijebu Yoruba, and western Igbo regalia, object types, or motifs demonstrate Benin influences. Distinguishable from the originals because of stylistic differences, they provide insight into desires to adopt Benin’s power through its art.

The final section of the exhibition examines the complexities of the last 111 years. In 1897, the British became the kingdom’s first successful invaders, their conquest resulting in the Oba’s exile, the looting and transport of thousands of palace treasures, and colonization. Although the Oba’s son ascended to the throne in 1914 and these events did not end artistic production, they proved a brutal cultural and political shock. The “Revivals” section reflects on the worldwide distribution of Benin artifacts, the rising international art market and fakery, continuities and changes in new works, and considers the power art wields, whether through repatriation issues or trans-Atlantic rebirths of Benin imagery in religion, African-American art, and home décor.

While IYARE! is a Penn product, it has a Benin voice as well. Proverbs encapsulating philosophy and cultural viewpoints open each section and title numerous labels. Some 21st century objects are the gifts of a high-ranking chief, and videos with music and crowd sounds enliven the exhibition. Literal Edo voices—including Philadelphia area executives and workers, students at Penn, and members of chiefly and royal families—will speak about their culture through associated web-site podcasts.

Curnow, Kathy, ed. IYARE! Splendor and Tension in Benin’s Palace Theatre. Self-published on Lulu.com, 2008.