stone) from Guatemala in the Museum’s Mesoamerican Gallery, 1961. UPM Image # 73485:8.

Museum Collection Number: NA11872

The entry, “Cantinflas, the Mexican comedian, in the Middle American Gallery, 1961,” catches one’s eye in the Museum’s photographic catalog. Appearing almost as an afterthought, this annotation and its accompanying photographs document a visit to the Museum by the world’s most famous Spanish-speaking, big screen comedian. Who was Cantinflas, and why did he visit our Museum? Cantinflas was the stage name of Mario Moreno Reyes.

Although virtually unknown in the United States, Moreno’s fame and continuing popularity as a comedian is without peer in Latin America. Born in 1911 in Mexico City, Moreno came of age in the 1940s—the golden age of Mexican cinema—and helped define the era. His most famous theater and film persona was that of the Mexican everyman—the pelado (literally “peeled” or “naked”)—a precariously employed slum dweller who was often recently transplanted to the city from the countryside. From the 1880s through the 1930s Mexico had undergone a period of intense economic, political, and industrial upheaval. This had created a large impoverished underclass, one that served as both the inspiration and audience for Cantinflas’ character.

#29-41-731) from Mexico. UPM Image # 73485:2.

Although the character of the pelado had a long history in Mexican entertainment, Moreno’s signature persona, Cantinflas, gained enormous popularity as the underdog who triumphed through wit or trickery over more powerful opponents. His forte was the comic use of language, the ability to talk constantly without saying anything. Using disconnected phrases that appeared to express deep thinking, Cantinflas would go round and round on a theme without ever explaining it. A typical tactic was to strike up a conversation— whether with a creditor he owed money, an authority figure he was trying to evade, or an attractive woman he wished to woo—and then make it sound so complicated that no one understood what they were talking about and did not realize when they were being manipulated or humiliated. A master of the evasive answer, Cantinflas’ manner of speaking became known in Spanish as “cantinflear,” defined by the Real Academia Española dictionary as “talking in an absurd or incongruous manner without actually saying anything” (hablar de forma disparatada e incongruente y sin decir nada).

Moreno’s career began in the 1930s in Mexican traveling theaters (carpas) where he played a number of roles before settling on the pelado. He made his film debut in 1936, and in 1940 the film Ahí está el detalle (There’s the Rub or That’s the Detail) propelled him to international fame. In 1956 he tasted Hollywood fame while playing Phileas Fogg’s valet, Passepartout, in Around the World in Eighty Days, for which he won a Golden Globe for best comedic actor. Although his next Hollywood film, Pepe (1960), earned him another Golden Globe nomination and a Special Achievement Award, it was a box-office flop. His humor, deeply rooted in the Spanish language, was difficult to translate for an English-speaking audience. Thereafter he returned to making Spanish-language films, and he was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Mexican Academy of Cinematographic Arts and Sciences in 1988.

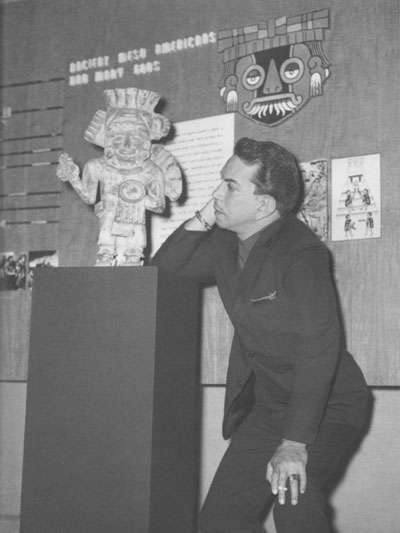

Cantinflas studies the Zapotec warrior. UPM Image # 73485:3

It is said that Charlie Chaplin once called Moreno “the greatest comedian in the world,” and Cantinflas is often referred to as the “Charlie Chaplin of Mexico.” Although relatively unknown in the United States, he has been honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and when he died in 1993, the U.S. Senate held a minute of silence to honor his memory.

We do not know the occasion of Moreno’s visit to the Museum in 1961 as additional records were either lost or have not yet come to light. Perhaps he was in the United States to attend the Golden Globe Awards, though that does not explain his trip to Philadelphia. Fortunately, the Museum’s photographer was on hand to take some pictures.

Seeing him in the Museum’s Mesoamerican Gallery does make sense. A native of Mexico, he may have been drawn to his country’s artifacts, particularly the pre-Columbian cultures of ancient Mexico, the ancestors of the pelado. Indeed, the character of Cantinflas can be seen to have descended from the trickster culture-hero found in the mythology of many North American and Mesoamerican cultures. These heroes gained advantage over their opponents through wit and trickery rather than force. That is Cantinflas—the trickster of words— who turned sense upside down until his enemies were subdued and the pelado was on top.