Glazed lions molded in relief on baked brick facades are relatively rare on the North American continent.One of the best of them has just been redisplayed at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto in its current “Art Treasures” show celebrating the museum’s fiftieth anniversary. Noted for many years for its Chinese collection, the museum is currently building its Near Eastern department under the able guidance of Curator Winifred Needler. Since World War II the R.O.M. has been developing an appetite for field work in the Near East, whetted by its possession of such superb pieces as the glazed Babylonian lion of about 600 B.C. illustrated here, which was purchased just before the war from the State Museum in Berlin.

That a piece of wall made twenty-five hundred years ago in the Neo-Babylonian Period should still arouse our interest shows that our reactions to objects with color and form and of mysterious origin differ little from those of our predecessors of a hundred years ago, who undertook the excavation of such famous ruins as Babylon and Susa. Attracted first by the color of these same fragments as a guide to their work, Robert Koldeway, the excavator of Babylon, points this out to us in his book The Excavations of Babylon when he says:

“The discovery of these enamelled bricks formed one of the motives for choosing Babylon as a site for excavation. As early as June 1887 I came across brightly colored fragments lying on the ground on the east side of the Kasr [street]. In December 1897 I collected some of these and brought them to Berlin, where the then Director of the Royal Museums, Richard Schine, recognized their significance. The digging commenced on March 26, 1899, with a transverse cut through the east front of the Kasr. The finely colored fragments made their appearance in great numbers, soon followed by the discovery of the eastern of the two parallel walls, the pavement of the processional roadway, and the western wall, which supplied us with the necessary orientation for further excavations.”

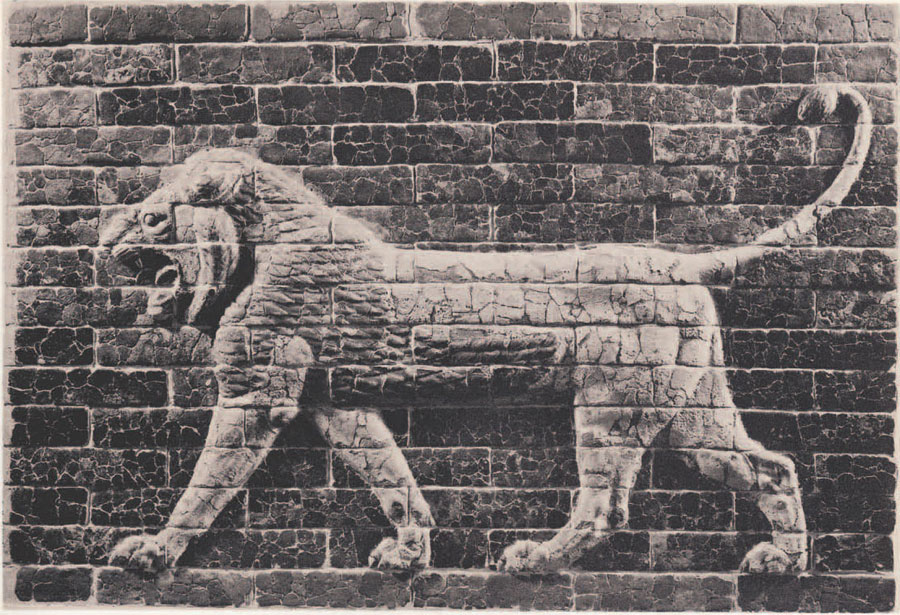

While such comments indicate the procedure which led to the excavation of the areas in which the glazed bricks were found, they gibe no hint of the complex task of excavating them. A glance at our illustration will show that the panel is made of innumerable small pieces of glazed molded brick reassembled to form the whole. Reassembling the pieces was an arduous task undertaken after excavation.

Some years before, in 1884, similar walls were unearthed by the early French excavators of Susa, M. Dieulafoy and his wife Jane. In her book, At Susa, the Ancient Capital of the Kings of Persia (translated by Frank L. White and published in Philadelphia in 1890 by Gebbie), this formidable woman (who on the opening day of excavations seized the pick herself and worked until exhausted!) describes the tedious job to be carried out in the blazing sun and dust: “Every block, broken sometimes into seven or eight fragments, is extracted with the point of a knife, traced on a paper ruled in squares, deposited in a basket on the bottom of which is drawn a number showing its order, and takes its way to camp” where “on rainy days” it was cleaned up! The restored panels now stand in the Louvre. Multiply the number of panels by the number of fragments of each brick (perhaps twenty-five) and you can imagine the detailed recording and patience required for the work. Two fragmentary bricks of the same period found at Ur may be seen in our own Mesopotamian gallery.

The work of restoring these panels is matched only by the effort of the potter in producing them in the first place. It has been suggested that the lion figure was modeled to scale either on a single clay panel or on a temporary wall with a plaster facing. In either instance, the relief had then to be cut apart into individual bricks, so that a separate mold could be made from each. The faces for the lions on the wall along Kasr Street in Babylon were made from a single mold, as shown by the fact that they are all the same regardless of which way the lion faces. The molds themselves had to be fired. The bricks were then cast from them and burned in a kiln. The burned bricks were laid out in order and each one marked at the top with an appropriate symbol to key it into the group. The contours of the animal were next drawn on in black and the areas so defined filled with liquid glaze of appropriate color. In the case of the lion shown here, which is four feet high and six feet wide, the mane is yellow, the body white, and the background blue-green. The fangs, claws, and tuft at the end of the tail are highlighted by touches of yellow. It comes from the throne room of Nebuchadnezzar and is one of a dado of snarling lions around the base of a larger wall decorated with glazed columns, lotus buds, and palmettes. Outside, along the street and on the famous Ishtar Gate, such lions were joined by dragons and bulls, the animal attributes of the gods Marduk and Adad. The lion itself was usually associated with the goddess Ishtar.

Wall panels of colored glazed brick were the decorative technique par excellence of the Neo-Babylonians, and the method was used for several centuries by the Persian overlords of Susa. At that site, which like Babylon did not have ready access to slabs of stone for wall reliefs, color was abundant and the repertoire was increased through the addition of archers, winged griffins, and winged human-headed lions. Somewhat earlier, the technique was used in Khorsabad at the Palace of Sargon and the Temple of Sin. Here a panel showed a procession of the king, a lion-eagle, a bull, a fig tree, a plough, and a minister of state. Other glazed panels are known from Assur. It seems quite likely that their origin found itself in the painted stone reliefs of such famous cities as Nimrud and Nineveh (represented in our Museum by the Assurnasirpal relief in the Mesopotamian gallery). Ultimately the wall leads us back to the glazed wall tiles of older Assyrian times and to the early use of glaze on the cylinder seals of the early fourth millennium.