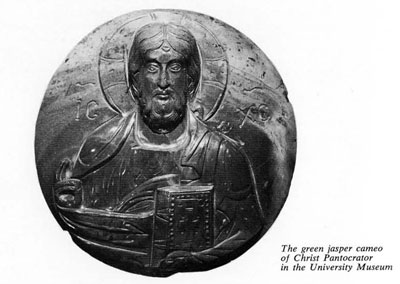

Museum Object Number: 29-128-575

One of the most important glyptic collections in the United States is the Maxwell Sommerville Collection at the University Museum. It compares favorably in its variety of pieces and their importance for a general study of glyptic arts with the few similar collections in great European museums in London, Paris, and Berlin.

Not only do the carved gems and the engraved intaglios of the Sommerville Collection come from the farthest corners of the earth–from China to the Islands of the Pacific, from South America to the European continent–but chronologically they reach from the most ancient period of Near Eastern history to the time of the European Neo-Classical movement. All these examples, made in more than fifty different kinds of semiprecious stones, were collected during the last century, and it seems that no piece was added to the collection after the 1890;s. Thus the careful, knowledgeable, and passionate search for these gems and cameos by two generations of Sommervilles has resulted in a great collection, which counts among its specimens world known and outstanding representatives of glyptic art of any given period. We have chosen one cameo to be discussed here, because to the best of our knowledge it is unique in size among the preserved pieces of Byzantine glyptic art. But for this very reason we do well to question its authenticity.

When first published by the collector in 1889 under the catalogue number 575, this piece was simply described as a “Byzantine sixth century cameo made of green oriental jasper, representing Christ.” However, since then our knowledge of Byzantine art has increased so much that it was possible to redate this cameo to the eleventh century when it was exhibited in Baltimore in 1947. It is our hope to ascribe an even closer date in the course of this discussion. This cameo was also included in the exhibition Cameo and Intaglio at the University Museum during the period November 1956 to March 1957. Since then it has not been displayed publicly.

An anonymous Byzantine artist carved the image of Christ, easily identified by the letters inscribed above His shoulders IC-XC. For this representation he chose the green oriental jasper, with darker green, yellow, and red veins in it which give it the name “bloodstone.” The surface of the stone has come down to us with relatively little damage. Its original polish, still preserved, glitters and reflects the light, showing both the high level of technical workmanship inherited from classical antiquity, and a profound understanding of the natural qualities of the stone itself. These qualities have been exploited by the artist to achieve a maximum of picturesqueness. Thus the lightest part of the stone is within and around the nimbus, and the beholder has the impression that a supernatural light shines from behind the figure, while the darkest part of the stone creates shadows around Christ’s shoulders.

The half-figure of Christ is represented within an almost perfect roundel, which measures about 8.5 cm. in diameter. The rim of the cameo comes just above His waist. The high relief of the figure is one of the outstanding features of this cameo. It is altogether about 2.12 cm. high, while the thickness of the background is about 0.84 cm. It is therefore one of the largest Byzantine cameos preserved in semiprecious stone. In this respect it can be compared favorably with the large cameos which have come down to us from the classical world and Early Christian period.

Such a representation of Christ in approximately half-figure is found also in other media and in different scales. It often appears in mosaics or frescoes in the domes of Byzantine churches, as in the Monastery of Daphne, and in objects of the minor arts such as enamels and ivory carvings.

On the Museum cameo Christ is depicted as a middle aged man with long, wavy hair parted in the middle, which is rather stylized, as is His beard. The medium-length, curly beard frames the long oval face, with its regular and serene features. His hair comes down on the forehead in a wavy line, leaving the ear lobes visible. A free lock of hair is usually represented in the middle of His forehead. However, on the cameo the lock either remained unfinished or, more likely, was stylized by the artist into a diamond shaped form. The eyebrows are strongly arched above the large eyes which are somewhat asymmetrical. This gives an effect of the gaze being fixed on the beholder. The nose is long, with prominent nostrils. The cheeks are thin, while the lips are rather full and framed with a moustache. The relief of the head projects farther from the background than the body (1.28 cm.), so its modelling is the strongest.

The head of Christ is framed by a nimbus in which the cross is inscribed. In all the representations of Christ and the saints only He wears the cross in a nimbus. This is His particular attribute and makes Him easily recognizable, even without the inscription. The bars of the cross are shown by double lines, which appear here as a purely decorative motif, though in earlier representations a three-dimensional effect was achieved in that the nimbus seemed to be behind the cross.

The garment of Christ is very simple and classical. His shirt, called a chiton, is made of a light material which softly falls over His body, making one large and several smaller U-shaped folds below His neck. A cloak called a himation is worn over the chiton. The heaviness of the himation is revealed in the folds which are formed as it wraps His body. The fashion in which the cloak is worn is very similar to that of an ancient philosopher draped in a toga. The folds of this mantle are gathered on the chest and pulled across it, leaving the right hand visible. This hand is extended in a quiet gesture of blessing slightly away from the body. The himation then follows the right shoulder of Christ, its free end falling over His left shoulder, draping completely His left hand, which holds the Gospel book. This codex rests against the folded mantle and the chest of Christ. It is closed with two clasps. The bookcover is decorated with a cross framed with jewels.

This representation of Christ belongs to the iconographic type called by the Byzantines The Pantocrator–The Ruler of All. Such an image of Christ enjoyed a great veneration among the Byzantines. We find it repeated over and over again from the Middle Byzantine period onward in many artistic media from mosaics to coins, from glyptic representations to enamels and frescoes.

In order to prove the authenticity of this cameo, as well as to ascribe to it a more precise date than the eleventh century in general, we must examine the other examples which are similar and dated.

The closest parallel to the Museum cameo that I was able to find is also an image of the Pantocrator carved in green jasper. It is now in Le Cabinet des Medailles of the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, No. 334. It is an oblong medallion, much smaller than the Museum cameo (H. 4.5 cm.; L. 3.5.cm.). Nevertheless, there is great similarity in the figure in general, and in many details, such as the stylization of the hair, the lock on the forehead, the beard, the blessing hand, the himation with the folds, the book, and even the style in which the carved surface of the face is treated. The only differences are the pearls placed in the cross and the uncovered hand in which Christ holds the Gospel. Undoubtedly both cameos are very close in date, and might have come from the same workshop.

However, for dating those pieces we must turn to another medium–ivory. The ivory carvings offer useful material for a comparative analysis on iconographic and stylistic grounds, since the similarity in technical execution leads to a closeness in style also. A certain number of these ivories which represent Christ and are comparable to the Museum cameo are preserved and also have been dated. This we hope will be very helpful in dating the piece under discussion.

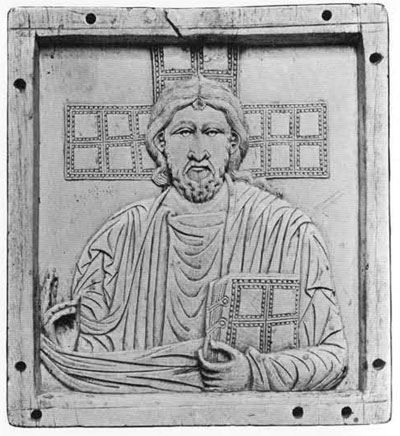

The style of the master of the Museum cameo may be characterized as follows. By emphasizing carved surfaces he achieved a strong plastic effect for the head of Christ. He used incised lines to describe details and to diminish the plastic effect of the body, which seems to disappear beyond the edge of the stone. At the same time the whole figure of Christ is strongly outlined by a sweeping line, starting from the book on His chest, going around His blessing hand, shoulder, and nimbus, coming down to the left shoulder, and ending in the veiled hand. It separates the bust from the background field and gives cohesion to the different elements within the figure. Such a balance between the plastic modeling and the use of very fine, incised and stylized lines is characteristic of the stylistic change in Byzantine art which took place during the late tenth and early eleventh century. This tendency toward a change from plastic modeling to linear rendering seen on the Museum cameo, can be followed on the ivories of that period. Thus, on an entire group of the ivory images of Christ, dated to the end of the tenth century, such as the panels from the Hermitage in Leningrad, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, and the Louvre in Paris, we find the same linear rendering of the beard and hair, and the very similar facial features, especially the long, narrow nose and prominent nostrils. The blessing hand extended at the side corresponds very closely to the same hand from the cameo, as does the drapery pulled over the chest. There are, however, noticeable differences: the large cross is not inscribed in a nimbus on the ivories; the drapery is rendered in many small, broken folds; and the uncovered hand carries the Gospel book. This closed codex is similar enough to that on the cameo if we compare the two clasps and the way it is foreshortened. The difference in the decoration of the book cover is inconsequential.

One detail of the iconography of Christ from the University Museum cameo should be noticed: the hand which holds the Gospel book is rather unusual. A covered hand holding a codex is more often associated with the Evangelist figures or with the Church Fathers. Only occasionally does Christ have His hands covered, mainly in such scenes as the Death of the Virgin. However, if the cameo were the only icon with such a characteristic we would be right to question whether or not this was an iconographic mistake made by a forger. But such is not the case. The covered hand of Christ seems to point to an old iconographic tradition, which was lost by the end of the twelfth century as far as the preserved images of the Pantocrator are concerned.

Such a covered hand holding the closed Gospel book can be found in several other ivory examples, thus probing itself as an authentic feature for the image of Christ. All these ivory examples predate the Museum cameo. We can mention here the ivory panel of Christ from Lyon, dated in the second half of the tenth century and also, the small medallion of Christ, placed within a cross on one side of an ivory diptych in Gotha. Numismatic evidence might point to an even earlier tradition. Some coins from the late seventh century, while depicting Christ under a different iconographic tradition, do seem to represent the veiled hand holding the Gospels.

The iconographic tradition of the veiled hand with Gospels is still found during the eleventh and twelfth centuries. An example is an enamel medallion formerly in the Zvenigorodsky collection (lost in Russia in the First World War). It is dated in the first half of the eleventh century. In spite of the differences–in the gesture of the blessing hand, in the garment, and especially in the eyes. Christ from the cameo gazes straight ahead, while He looks to the side on the enamel medallion, as He does in the mosaic in the monastery at Daphne. This seems to be the sign of a later iconographic development of the image of Christ.

We also find Christ holding the Gospels in a covered hand on a twelfth century fresco in the church of Sts. Cosmos and Damian in Kastoria. This must be a provincial reflection of an older iconographic tradition. The later representations of the Pantocrator usually shoe His hand uncovered.

In the Byzantine art of the sixth and seventh centuries, along with the representation of Christ as a middle aged man with long wacy hair and full beard, there were several other images of Christ, predominant among which was that of a younger man, with shorter beard and short curly hair, as we see Him on the golden solidus of Justinian II. This tradition of several different iconographic types dor the image of Christ was interrupted by the long struggle (A.D. 726-843) between those who favored the use of images, mainly of Christ, and those who opposed them. The final victory fell to those who favored images. The representations of Christ and the saints were revived, and the type of Christ as depicted on our cameo became the predominant representation for Christ Pantocrator. Such an image of Christ is depicted in mosaic above the narthex door of the Hagia Sophia; it is also repeated on many coins, as on the coins of Nicephor Phocas (963-969), John Zimisces (969-976), and Basil II (976-1025).

In the Byzantine art of the sixth and seventh centuries, along with the representation of Christ as a middle aged man with long wacy hair and full beard, there were several other images of Christ, predominant among which was that of a younger man, with shorter beard and short curly hair, as we see Him on the golden solidus of Justinian II. This tradition of several different iconographic types dor the image of Christ was interrupted by the long struggle (A.D. 726-843) between those who favored the use of images, mainly of Christ, and those who opposed them. The final victory fell to those who favored images. The representations of Christ and the saints were revived, and the type of Christ as depicted on our cameo became the predominant representation for Christ Pantocrator. Such an image of Christ is depicted in mosaic above the narthex door of the Hagia Sophia; it is also repeated on many coins, as on the coins of Nicephor Phocas (963-969), John Zimisces (969-976), and Basil II (976-1025).

The origin of this type has recently been traced by James D. Brackenridge to the famous statue by Pheidias, of Zeus Olympian, which once stood in the city of Constantinople. Indeed, if we compare two faces, one from a copy of Pheidias’ Zeus, now in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the other from any of the above mentioned images, including the cameo in the University Museum, we can observe a direct resemblance which goes beyond a majestic appearance, nor is this resemblance lost through the typical Byzantine elongation of the facial features.

All these iconographic and stylistic comparisons not only seem to prove the authenticity of the University Museum green jasper cameo of Christ, but also seem to point strongly to the date of its creation. Although the coins are cited mainly as iconographic parallels, the golden coins of John Zimisces representing Christ seem to come closest to the cameo stylistically, in general outline of the figure, the shape of the head, face, hair, beard, in the draping of the himation, and in the strongly outlined cross inscribed in the nimbus. However, the hand holding the book is bare rather than covered as on the cameo.

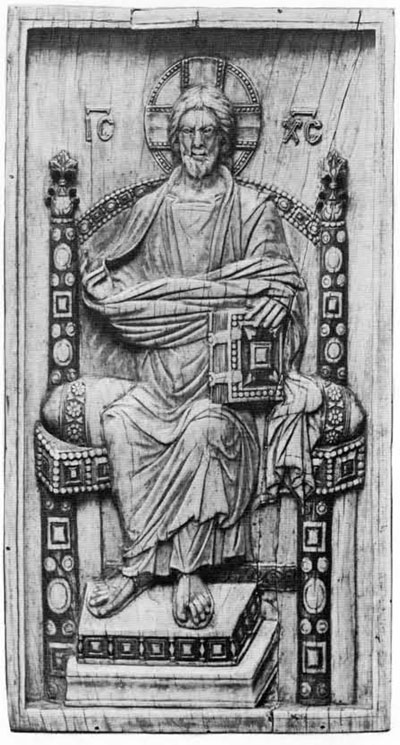

The other ivories from the second half of the tenth century representing Christ are also very close to the cameo. To show only one more example of that period, we have selected an ivory panel representing Christ enthroned. This panel is now in Basel, in the collection of Robert von Hirsch. The face and expression of Christ on it come very close to the Museum example. On the other hand, the enamel medallion from the first half of the eleventh century shows the change of expression, due to the sidewise glance of Christ. All this comparative evidence in addition to the evidence provided by the style of the cameo itself–the balance of the plastic and linear elements within the figure–points to a transitional period of the late Macedoinan dynasty, to the period of the late tenth, or at the latest the early eleventh century, as the time of the execution of this cameo.

Once established and popularly accepted, iconography of such an image tended to preserve its traditional appearance, and stylistic and iconographic changes were very slow. This point can be illustrated well when comparing the small cameo from the Museum with the large mosaic medallion of the Pantocrator from the dome in the Monastery of Daphne, dated about 1100. In spite of different dates, and scales, we find still a great deal of similarity between the two images. There are however noticeable differences in the gesture of the blessing hand, in the hand which holds the Gospels, and in the eyes. The garment, the facial type, and especially the hair and beard show affinities unexpected in two such different artistic media. However, the mosaic image shows a greater emphasis on stylized lines, which points to a definitely later date.

There is still another problem: Where could such a cameo have been used? An examination of its rim shows that it was cut in such a way that it could be inlaid into a background of another material. The back surface of the cameo is perfectly smooth. There might be several equally acceptable possibilities for the use of this and similar cameos in Byzantium. It might have been inlaid into a golden field and suspended on a golden chain as a pectoral ornament. The weight of the cameo alone is 144 gr., which is not too heavy to be worn. If that were the case, such an ornament would be worthy of the emperor or patriarch alone. It could have decorated a church vessel, for example a golden or silver chalice, worthy of the altar of Hagia Sophia. We know about such vessels through written sources more than through the few surviving pieces, for such expensive objects were often melted down to finance a campaign to defend the empire, or were the first prize of those who looted the Byzantine cities. It could also have been the central medallion of a golden, free-standing, jeweled cross, similar to the silver cross of Justin II (568-578) now in the Vatican. The idea that this cameo with the Pantocrator in it was placed as a central medallion in a cross leads us to a very tempting possibility. Perhaps it was originally a part of a sumptuous Gospel-book cover. If so, the effect would have been quite similar to the representation of the cross with the medallion of Christ on the one wing of an ivory diptych from the Gotha Museum, which dates to the tenth century. It is 29 cm. high. The representation of Christ in this medallion is noticeably similar to the cameo image in almost every detail. A silver bookcover able to bear a cross with the green jasper cameo as the central medallion (its diameter being about 8.5 cm.) would have to be approximately twice as high as the Gotha wing, but it would not exceed the dimensions of a folio book of today. As a matter of fact, we do possess some large early mediaeval books, such as the Rabbula Gospels in the Laurenziana in Florence, whose covers could have carried a medallion of this size. Though each of these suggestions is very attractive, new evidence would be needed for a definite conclusion as to the purpose of this cameo. Whatever its use may have been, the cameo’s outstanding excellence points to its origin in the Imperial workshop in Constantinople. We know nothing of its history during the hundreds of years before it found its way into the Sommerville collection. Only chance has preserved for us and generations to come, this beautiful piece, as one of the witnesses of a high civilization long passed.