Like people in many other times and places, indigenous Fijians are firm believers in a glorious but disappeared past. In the old days, many Fijians say, the ancestors were big and strong, everyone worked together on communal projects, and chiefs had unquestioned authority. In the present, by contrast, people see comparative weakness and disorder.

Like people in many other times and places, indigenous Fijians are firm believers in a glorious but disappeared past. In the old days, many Fijians say, the ancestors were big and strong, everyone worked together on communal projects, and chiefs had unquestioned authority. In the present, by contrast, people see comparative weakness and disorder.

The myth of a powerful past is not just nostalgia for Fijians—the stories they tell about the old days inspire considerable anxiety. The anxieties surface in many forms, such as fears that the powerful ancestors can curse people in the present with sickness, poverty, and other maladies. The theme of decline and loss is more pervasive than this, however, extending to general concerns about the loss of knowledge and custom. For example, people believe that knowledge of proper land boundaries (and, therefore, of legitimate landownership) has been lost and that the social order is vulnerable as a result.

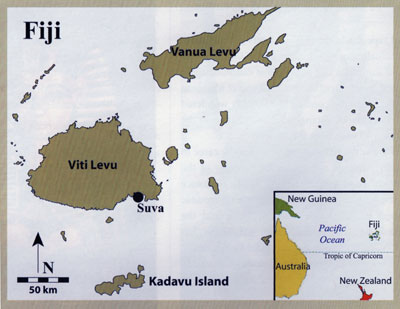

Perhaps the most intriguing symbol of perceived social decline in the Fijian universe is kava drinking. Kava, called yaqona in Fijian, is a beverage made from the dried and crushed roots and stems of a pepper shrub, Piper methysticum. Cultivated and drunk throughout much of the southwestern Pacific, kava is the most copiously drunk social beverage in Fiji. In rural Kadavu Island, most adult men drink kava for hours every night, and women also drink a fair amount, although not quite as much as men do. Drinking is a means of relaxation, because when the crushed kava plant is infused into water, it gives the drinker a pleasantly numb sensation. Kava is a soporific, gently putting the drinker to sleep; unlike alcohol, it does not change one’s mood or emotions.

Many indigenous Fijians, however, complain about kava drinking. They sometimes even complain about kava while drinking it because public forums are held around the kava bowl. People complain that too many people drink nowadays, and that they drink too much. They say that it makes people too lazy to work or go to church, and that men come home from drinking sessions too tired to satisfy their wives. In short, kava is seen as a force that weakens individual bodies and the social order, numbing and nudging Fijian society along its slow and persistent path of decline. A typical sentiment heard in Kadavu is, “Nowadays, too many people drink too much kava, and it wasn’t this way in the old days.”

Yet kava is also cherished as a political emblem, the very epitome of proper custom. Indeed, a big event such as a wedding, funeral, or fundraiser demands plenty of kava drinking. To host guests without offering kava would be unthinkable. It is not only the elixir of sociality, but also a marker of social significance. The few Christian sects, such as evangelical groups like Seventh Day Adventists, that ban kava drinking must still allow guests to drink kava on important public occasions, because not drinking kava would feel improper, as if the ceremony was unimportant or invalid.

A persistent tension crackles along the nerve centers of rural Fijian public life—kava is drunk in large amounts by many people every night, but the same people can heartily decry excessive kava drinking. Fijians are not being hypocritical in any sense, for their attitudes and practices can be reconciled when one looks more closely at the ways kava drinking is embedded in their political and religious systems.

Kava’s Compulsive Force

June 4, 2003: Eight of us get in the Methodist Church boat in Tavuki village to go to Yakita village, a short trip up the northwest coast of Kadavu Island. The weather is fine and our trip begins smoothly, the small craft cutting across the iridescent blue lagoon. We are heading to the Methodist Church quarterly conference. Because we are going to a church meeting, the leading religious authorities are on board—the superintendent minister, the catechist, their wives, and the head steward, as well as two men in charge of the boat.

The village we are coming from, Tavuki, is the home of the paramount chief of Kadavu, the Tui Tavuki. The trip from Tavuki to Yakita is not especially long, no more than half an hour in a boat with a 25-horsepower engine. Soon we are drawing up to Yawe’s stony coast, with the great volcanic cone of Nabukelevu looming in the far west.

When we reach Yakita, however, a man on shore tells us that the quarterly meeting is supposed to be held in Nalotu village instead. Nalotu is very close by, so it is no trouble for us to go there. When we land at Nalotu, however, the situation becomes a bit vexed. One of the boat’s operators tells a man on shore in Nalotu that we are there for “na bose” (the meeting), and the man responds, “Bose yava?” (What meeting?). It turns out that when the meeting’s date had been announced days before on the radio, no one from Yawe heard the broadcast. Our delegation has caught everyone by surprise. There will be no meeting after all, because no one in Yawe is prepared for it.

This, however, hardly means that the day’s business is finished. The people of Yawe cannot possibly let us return to Tavuki without acknowledging our arrival, though our coming was unexpected and our business thwarted. We are visitors, and visitors with distinguished members—the leading church minister and the head steward, who was a Tavuki nobleman, are especially worthy of displays of respect. So, in accordance with customary expectations, we are now welcomed with an isevusevu, a ceremonial presentation of the kava plant. Meanwhile, the men of Nalotu prepare the beverage for drinking.

Tavuki and Yawe have a relationship known as vitabani, which literally means “sides.” It derives from the fact that Tavuki and Yawe, though neighbors on the island of Kadavu and sharing many ties of intermarriage, have a fractious history of warfare. In other words, they used to be enemies, and although no one clubs each other over the head anymore, Tavukians and Yaweans still like to “fight” around the kava bowl by trying to out-drink each other while joking exuberantly at each other’s expense. The beverage has a bitter taste, and if drunk in great excess, it can make the drinker vomit. Because it numbs the body, especially turning the legs wobbly and gradually making a person sleepy, vigorous kava drinking requires sustained energy. The camaraderie around the kava bowl, however, usually helps keep people awake.

And so it goes for the first five hours or so at Nalotu, approximately 25 rounds of kava in all. I am feeling tired and nauseated by this point, so I accept the invitation to have some lunch. This undoubtedly disappoints the Tavuki men who are staying at the bowl to display their unquenchable thirst for kava and who want the Tavuki party to remain united. But I am not the only one to leave early. The superintendent minister himself, who is rare for not being fond of kava, leaves at the same time. After eating, we relax and chat with a man from Yawe who keeps us company. I keep expecting the kava session will end before too long—proof that although I have stayed in Kadavu long enough to learn the language, I can still make profoundly stupid mistakes. Of course (in hindsight, I see it), the session goes on and on—we are in Yawe, after all, so Tavuki men must keep drinking vigorously, and the four Tavuki men still at the session (the head steward, the catechist, and the two boatmen) are all kava champions, masculine paradigms of thirsty consumption.

In the end, they drink for a total of 11 hours. When we return to Tavuki that night, I ask the minister why he had drunk kava if he did not enjoy it, and he said simply that it was impossible to refuse this show of respect. Evidently he felt that five hours of drinking was a respectful showing.

The events of June 4th might sound extraordinary. After all, for many Western readers, a cancelled meeting does not usually result in 11 hours of drinking and storytelling. I described this event at length, however, precisely because it was so ordinary for daily life in Kadavu. Eleven hours is a lot for a regular day’s drinking, but on important occasions, sessions become marathons.

A Cultivated Taste

When the kava shrub is at least three years old, it is harvested by pulling it from the ground with its roots intact. If it is going to be offered as a formal ceremonial presentation—such as an isevusevu, the offering between guests and hosts—the plant may be kept intact so that it can be presented in its entirety, looking something like a knobby set of bagpipes. Often, however, the stems are cut off so that the plant may be pulled up more easily. Upon returning to the village, the gardener will wash the roots and stems, chop them up into relatively small pieces, and then put them onto a sheet of corrugated iron to dry in the sun. Once the kava has dried for about three days, it becomes almost crisp and ready for pounding.

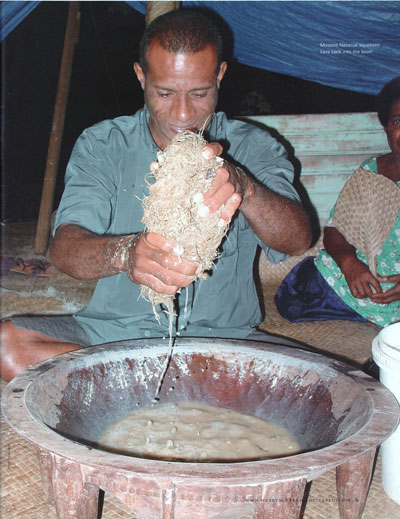

The roots and stems are pounded using a mortar and pestle, usually a large hollowed-out log and a metal bar. When reduced to a powder, the kava is soaked in water and strained using the stringy inner bark of a hibiscus tree. Mixing with the bark strainer (unu) is time consuming, with a large bowl of kava taking perhaps 10 minutes to mix properly, after which there should be no gritty dregs. This, at least, is the traditional method still used in western Kadavu. In eastern Kadavu, and in much of the rest of Fiji, people now mix kava using thin cloth bags made from the same material as Indian women’s saris. The drink is served in shells made from the dried and polished halves of coconuts. The kava bowl itself is often a simple but elegant form carved from a single block of hardwood, a species called vesi in Fijian (Intsia bijuga).

- From offshore one can see parts of Tavuki village and neighboring Nagonedau village.

-

(left) At large kava-drinking sessions, the beverage may be prepared outside the house where most of the people are gathered. Here, a young woman hands a cup of kava to one of the preparers waiting outside.

(right) Taniela Botea stands behind a kava plant he has freshly uprooted.

-

(left) Ratu Josaia Veibataki chops a stalk and roots into smaller pieces which will be dried up.

(right) Children sit on a rooftop where roots are drying.

- Taniela Bolea lays kava roots onto a corrugated iron rooftop so they will dry in the sun.

No matter how well prepared, kava always has a somewhat bitter, dusty, earthy aroma and taste. Unfortunately, this has earned it some memorable insults from popular writers, with James Michener in Return to Paradise calling kava “slimy” and Paul Theroux in The Happy Isles of Oceania: Paddling the Pacific dismissing it as “revolting.” Perhaps the most evocative description comes from anthropologist Clellan Ford, who said that kava tasted “like the smell of a cedar lead pencil when it is sharpened.” Even veteran Fijian drinkers sometimes joke about kava’s bitterness, grimacing and saying “kamikamica” (sweet) sarcastically after a strong cupful. The truth is that a well-mixed bowl of kava should be smooth and somewhat refreshing.

Casual evening drinking sessions can be relatively formal if chiefs are present. Chiefs are generally men who inherit their position patrilineally (from their father’s side), and their authority is highly visible at any kava session. They are always served first, and are among the few people who keep their own cups on the theory that it would harm people of lesser power to drink from the same vessel as a potent chief. At drinking sessions with chiefs, commoners will not joke as much, and the tone of conversation will be more markedly polite, unless, of course, one of the chiefs happens to be a great joker himself. If there are no chiefs present, things can be more relaxed, with more boisterous storytelling and whoops of exuberant laughter. Around Christmas and New Year’s, people are determined to have a good time, and kava sessions can become riotous occasions of flirting, singing, and such festive customs as mock-stealing a person’s property, “imprisoning it,” and demanding a ransom. One kind of ransom payment, of course, is kava, and both perpetrators and victims relish the game.

A Consuming Tradition

Bottom, in a joking flirtation, an older woman forces a younger man to drink, physically holding the cup to his lips.

Early during my field research, I struggled with the question of why Fijians drank so much kava if they saw it as a social problem. Complicating the picture, I was told that kava drinking was a way to get in touch with ancestral spirits.

Methodists, who make up more than 90% of Kadavu’s population, drink kava heartily. So do Roman Catholics, Kadavu’s second-largest religious denomination. And both groups drink on Sundays after church. However, people claim that drinking kava can put one into contact with ancestral spirits who might have evil designs upon living people; thus to drink kava alone is considered “witchcraft.” The unstated rationale seems to be that no one drinks alone—conviviality is the heart of a kava session—so if you are seen drinking alone, your fellow consumers must be the invisible forces haunting the margins of village life.

One can hear fanciful tales of how kava is used to get in touch with evil spirits, pouring it over grave sites, for example, or into the lagoon. Some kinds of kava magic are subtler, however, such as dipping one’s finger into the cup as one drinks, or simply thinking bad thoughts at the time. Because kava has this demonic undercurrent, people find the idea of using kava in Christian communion to be a perversion. Inspired by an article I read about Samoan Catholics using kava instead of wine, I asked several Kadavuans if they would ever consider doing the same, and the answer was always an emphatic “no.” Indeed, in 1999, a man who was convicted of molestation claimed that one of the reasons his life was under a “curse” was that the minister had accidentally baptized him in kava instead of holy water.

So if kava is a cause of social decline and, moreover, is a way to get in touch with dangerous non-Christian forces, why is it so enormously successful at bringing people together in harmonious interaction? This question, of course, is built on the false premise that people should avoid what they criticize. One does not need to look to Fiji for examples of people doing things they say they should not. I argue, however, that the situation is particularly understandable in Fiji when kava is seen as an emblem of everything else that Fijians fear they are losing. When people lament the loss of size and strength, the weakening of kinship bonds, the threatened nature of land ownership, and the perceived loss of political power, kava becomes both good to drink with and good to think with. It relaxes people but, more importantly, brings them together, providing the situational focus in which people talk through these issues. Ironically, kava drinking also proves people’s stories as they tell them. In describing decline while drinking a numbing relaxant, the talking, doing, and feeling are all wrapped up together in a single moment.

Kava serves as an emblem of tradition, but it also provides hope for financial development and the security that such development promises. Farmers realize they can make money by selling kava to other Fijians as well as the large number of Indian citizens in Fiji, who also drink the beverage enthusiastically. At the central market in Fiji’s capital, Suva, many vendors proudly advertise that they carry Kadavuan kava, noted for its high quality. In addition, kava is moving into international markets, not only to supply overseas communities of Fijians and other Pacific Islanders (and even the odd anthropologist), but since the 1990s it has also been marketed in pill form as a stress reliever for Western workaholics.

Kava’s status is deeply vexed—relaxing but inspiring, a bedrock of security with a shadowy aura of danger, an immemorial tradition that provides the best hope of development. Perhaps the most telling sign of this vexed status is people’s use of the term mateni. Mateni literally means “drunk,” and, as self-consciously good Christians, Kadavuans often lament drunkenness and say that there is entirely too much of it. Yet these assertions are made wryly, entirely serious but also half-joking. Evidently, the happiness and security that many indigenous Fijians feel in kava-drinking sessions outweighs by far their concerns about the beverage’s dangerous aspects.

Lebot, Vincent, Mark Merlin, and Lamont Lindstrom. Kava: The Pacific Drug. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992.

Tomlinson, Matt. “Perpetual Lament: Christianity and Sensations of Historical Decline in Fiji.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 10 (2004):653-73.

Toren, Christina. “The Drinker as Chief or Rebel: Kava and Alcohol in Fiji.” In Gender, Drink, and Drugs, edited by M. McDonald, pp. 153-73. Oxford: Berg, 1994.

Turner, James W. “Substance, Symbol, and Practice: The Power of Kava in Fijian Society.” Canberra Anthropology 18-1&2 (1995):97-118.