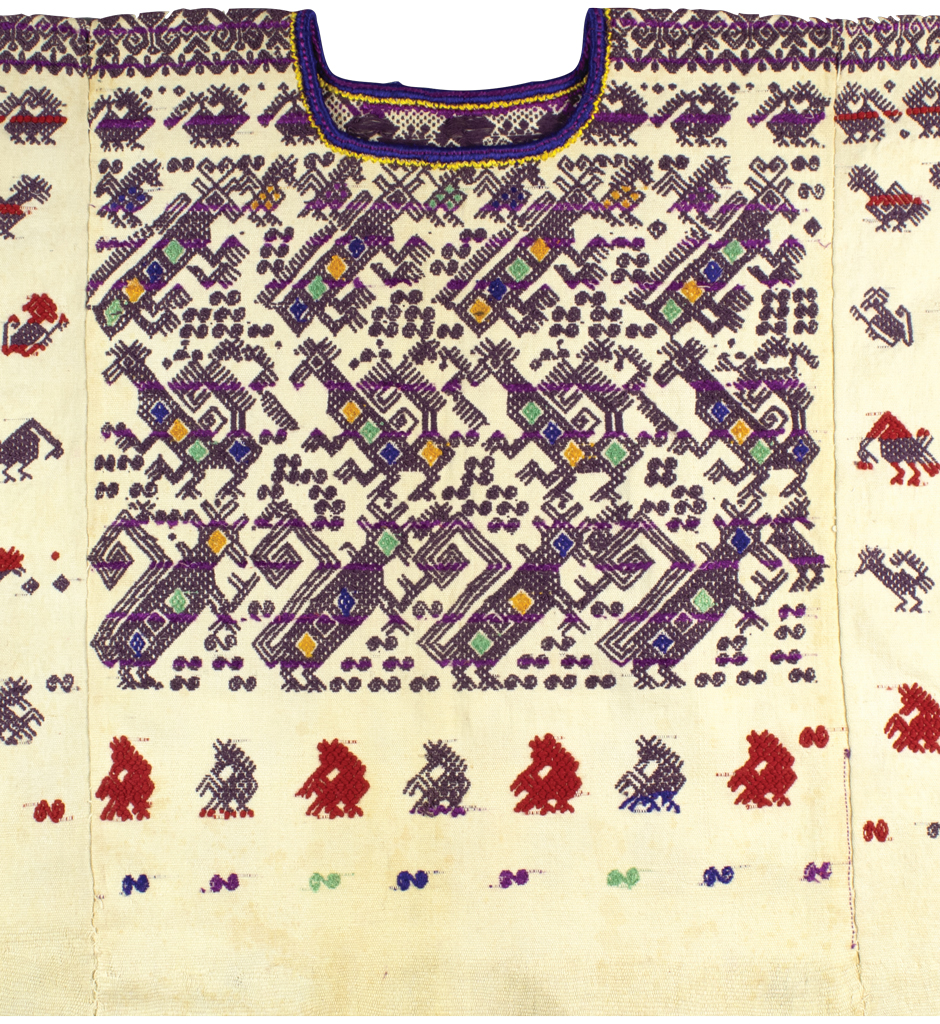

FOR 1,500 YEARS, MAYA WOMEN HAVE WOVEN cotton garments with designs that depict the Maya cosmos and supernatural beings that sustain their world. A continuous thread through the centuries, highland Maya women of Guatemala have never stopped weaving as their communities have adapted to the massive demands of Spanish colonization, natural disasters, and the devastating Civil War (1960– 1996). In the 21st century, as old beliefs and customs that still survive blend with or diverge from Christian ritual, Maya garments continue to strengthen Maya bodies, identities, and solidarities in new ways.

Today, roughly 10 million Guatemalan Maya men, women, and children— speaking 21 different languages—choose to wear indigenous garments every day or on special occasions. In some towns people still wear the unifying locally-specific style of their community. Regional and new pan-Maya styles are worn as well. Indigenous clothing is especially visible on religious holidays, and regional pageants and competitions celebrate and promote traditional dress. Urban Maya often experience discrimination and many choose to wear Western clothes to obscure their indigenous identity. This trend continues as young men and women seek opportunities for work and education in Guatemalan cities and beyond.

THE ROOTS OF MAYA WEAVING

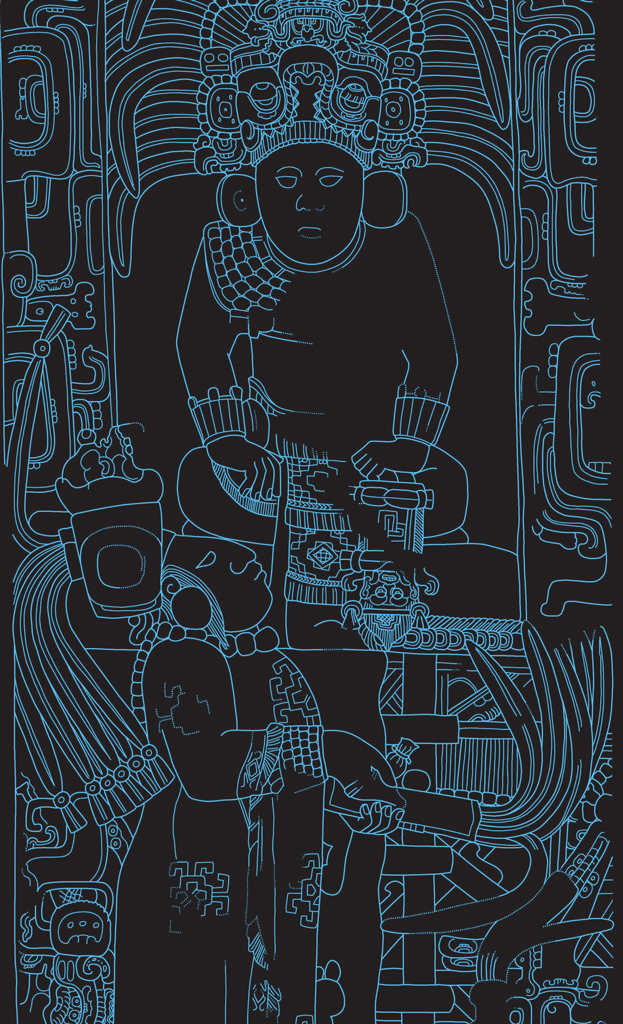

Originally woven of local brown and white cotton, early Maya weaving was associated with the ancient Maya Goddess Chak Chel (Great Rainbow), patroness of weaving, childbirth, and world destruction. In legend she wove the four-sided framework of the world into existence on her back-strap loom tied to the world tree. According to Lilly de Jongh Osborne, collector of Maya textiles, with its roots in the underworld and its canopy holding up the sky, the tree is the axis mundi through which life is regenerated anew (1965). The dress of ancient Maya kings, queens, and commoners visible in Classic Period art is similar to that worn by Maya descendants today.

Through the centuries, Maya weavers have enthusiastically incorporated new tools and materials received through trade—floor looms, wool, and dyes from Europe, and brilliant silk floss from China. Early in the Historic Period, machine-spun cotton yarns in bright colors were imported from Germany and England, and by 1885 colorful yarns and cotton yardage were produced locally in Guatemala as well. The use of jaspe (a type of resist-dyed ikat fabric, shown on page 34) flourished in the second half of the 20th century, and less expensive synthetic rayon and acrylics have been incorporated since the 1960s. Despite these many changes, fundamental design principles and technologies that mark Maya weaving’s sacred beginnings have generally remained constant, as have gender rules around the production of cloth. The backstrap loom is still used by Maya women, and ritual garments—larger, more elaborate, and of the finest materials—are worn draped over the body with the four selvedges neither cut nor tailored.

RIGHT: Man in cofradia garments, Sololá, Kaqchikel Maya, 1942. Photo by Lilly de Jongh Osborne.

As known from the study of Maya textiles, Barbara Knoke de Arathoon (2016) suggests that the Spanish-imposed cofradia system of religious brotherhood helped preserve textile traditions in many highland towns.

Blending Maya and Catholic beliefs, cofradia are ritual organizations devoted to the care and protection of sacred religious icons. Annual ceremonies care for and please the saints and spirits with lavish processions, beautiful clothing, food, and prayer. Cofradia officers who orchestrate and finance these events are distinguished by their high-status garments made anew each year, which often mirror the clothes worn by the saint statues themselves. This ritual protocol keeps the textile traditions alive.

THE OSBORNE COLLECTION OF MAYA TEXTILES

The Penn Museum’s collection of 1,700 20th-century Maya textiles includes men’s and women’s garments gathered in over 80 communities across the Guatemalan highlands. The core collection, described only briefly here and highlighted in the new Mexico and Central America Gallery, was assembled before 1933 by Lilly de Jongh Osborne [1883–1975]. Of Dutch heritage and the spouse of a managing engineer of the International Railways of Central America, Osborne lived in Guatemala City for 71 years. She travelled regularly in trousers and by mule to remote mountain towns with an interpreter. Her keen eye and knowledge of the region enabled her to situate Maya textiles within their social and historical contexts. She purchased village-specific dress, noting historic linkages to Maya ethnic families and archaeological sites when possible. She also documented the subtleties of the Maya caste system as seen in clothing, a feature that distinguishes her collection. Though her collecting strategy was not systematic, she noted 18 communities that emphasized costumbre (traditional Maya customs) and described the use of cloth in ritual and life cycle events, fiestas, weddings, baptisms, and funerals. Some early 20th-century design motifs were like those of the ancestors, and, according to Osborne, though weavers were often unaware of their original meanings, enduring trends conveyed family symbols, cycles of fertility, natural phenomena, supernatural beings, and ideas of cosmology. She collected several complete outfits and noted which garments were coveted and widely traded among the Maya themselves—wool blankets from Momostenango; woven belts from Oaxaca, Mexico; and silk brocades from Quetzaltenango. Emphasizing the lived social contexts and spirit with which textiles were made and used, Osborne acknowledged the quietly subversive and protective intentionality of Maya cloth in the first half of the 20th century. She named her closest Maya sources and returned their favors with payments, medicines, and gifts of food. She also noted the centuries of oppression and suffering the Maya endured at the hands of outsiders. In 1933, she loaned her first collection of 400 pieces to the Penn Museum. Immediately displayed in the South American Hall and soon afterward at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, the Penn Museum purchased her collection in 1942. After publishing the first monograph on Guatemalan textiles in 1935, Osborne continued to collect through the 1940s and 1950s and less so in the 1960s; her second collection of 487 additional garments was transferred to the Museum by her children in 1985.

MAYA TEXTILES TODAY

Since Osborne’s era, the devastating earthquake of 1976 and decades of Civil War have brought destruction, armed conflict, and genocide to Guatemala. Maya survivors fled to the mountains or to the cities to find jobs, and many, wanting to remain unnoticed, abandoned their indigenous dress. Though support has improved since the Peace Accords of 1996, Guatemalan society remains highly unequal, and indigenous families struggle within a system offering little or no rights to land and opportunities. Many seek education, wage work, and to emigrate to America, and evangelical Protestantism has helped some find a new beginning.

Starting in the late 20th century Maya textiles have taken on new meanings. A new pan-Maya style supports indigenous solidarity without revealing the home community or ethnic identity of the wearer. Rosario Miralbés de Polanco (2013) indicates that, with this trend, more women are dressing as they wish, using designs indiscriminately and preferring outfits that harmonize in color. This represents a shift in cloths’ meaning from the local and regional to pan-national and ethnic associations. Manuela Picq (2017) suggests that, most recently, and in response to longstanding economic exploitation, inequality, and poverty, women’s weaving cooperatives are helping women advocate for cultural property laws to protect textile designs from corporations and mass production.

Now, as in the past, Maya textiles are metaphorical recreations of the Maya world. Though they have changed through time, they still retain the connections that index Maya origins. Today’s weavers and wearers perpetuate this iconic art form as they negotiate their indigenous identities and solidarities in new ways. Wherever she may be, when a Maya woman puts on her huipil, she is at the center of the Maya world.

NOTE: A new selection of textiles from the American Section collection will rotate into the Mexico and Central America Gallery each year.

Lucy Fowler Williams, Ph.D., is Associate Curator and Sabloff Keeper of Collections in the American Section. She also served as a curator for the Mexico and Central America Gallery.

FOR FURTHER READING

Altman, P. and C. West. Threads of Identity, Maya Costume of the 1960s in Highland Guatemala. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1992.

Knoke de Arathoon, B., editor. Cofradia, Texture and Color. Guatemala City: Ixchel Museum of Indigenous Dress, 2016.

Mayen de Castellanos, G. Tzute and Hierarchy in Sololá. Museo Ixchel de Traje Indigena de Guatemala, Museum Monograph, English Language version, 1988.

Miralbés de Polanco, R. “Maya Attire and the Process of its Massification,” in Ancestry and Artistry, Maya Textiles from Guatemala, Roxane Shaughnessy, ed., Toronto: Textile Museum of Canada, pp. 88–99, 2013.

Holsbeke, M. and J. Montoya, eds. With their Hands and their Eyes: Maya Textiles, Mirrors of a World View. Antwerpen: Ethnografisch Museum, 2003.

Osborne, L. de J. “Osborne Collection of Guatemala Textiles,” American Section Records, Penn Museum Archives, 1933.

Osborne, L. de J. “Making A Textile Collection,” Bulletin of the Pan American Union, Vol. X, pp. 275–279, 1933.

Osborne, L. de J. Guatemala Textiles. Middle American Research Series, Publication No. 6, New Orleans: Tulane University, 1935.

Osborne, L. de J. Indian Crafts of Guatemala and El Salvador. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1965.

Picq, M. “Maya Weavers Propose a Collective Intellectual Property Law.” Translated by Daniel Dayle, March 14, 2017. https://intercontinentalcry.org/maya-weavers-propose-collective- intellectual-property-law/

Rowe, A. A Century of Change: Guatemalan Textiles. Washington, DC: Textile Museum, 1981.