Ancient notices of the Greek colony of Pithekoussai, the present island of Ischia in the Bay of Naples, are surprisingly scanty and often contradictory. Its early history seems to have been as obscure to ancient writers as it was to modern scholars before systematic archaeological exploration began there in recent years. Even the significance of its name was a point of contention in antiquity, the geographer Strabo claiming, with impeccable philology, that it derived from the Greek for monkey (pithekos), while Pliny drew attention to the extensive pottery workings on the island in his own time (Greek pithos, pithakne, a large storage vessel). It was further alleged that the early colonists prospered because of their gold mines and the fertility of the island’s soil. But apes there certainly never were on “Monkey Island” nor is gold geologically possible. Flat, cultivable land, moreover, is almost totally lacking on Ischia, although vineyards now thrive on its heavily terraced slopes.

Ancient notices of the Greek colony of Pithekoussai, the present island of Ischia in the Bay of Naples, are surprisingly scanty and often contradictory. Its early history seems to have been as obscure to ancient writers as it was to modern scholars before systematic archaeological exploration began there in recent years. Even the significance of its name was a point of contention in antiquity, the geographer Strabo claiming, with impeccable philology, that it derived from the Greek for monkey (pithekos), while Pliny drew attention to the extensive pottery workings on the island in his own time (Greek pithos, pithakne, a large storage vessel). It was further alleged that the early colonists prospered because of their gold mines and the fertility of the island’s soil. But apes there certainly never were on “Monkey Island” nor is gold geologically possible. Flat, cultivable land, moreover, is almost totally lacking on Ischia, although vineyards now thrive on its heavily terraced slopes.

Wine, in fact, used to be the island’s gold, though it has since been overtaken in economic importance by the seasonal influx of tourists. Considering the resulting boom in hotel and villa construction which continues at present, it was only just in time that controlled archaeological excavations began twenty years ago near the town of Lacco Ameno. For, despite the fact that the site of the ancient settlement at the northwest tip of the island had been recognized since the end of the eighteenth century, it is only since 1952 that it has become the object of intensive research. The work of Dr. Giorgio Buchner, senior member of the Superintendency of Antiquities of Naples, has amply confirmed the ancient tradition that Pithekoussai was the oldest Greek colony in Italy or Sicily (see Expedition, Summer 1966). What is more, excavation has demonstrated that the town had an importance and prosperity far out of proportion to the brief remarks about it by ancient authors.

But the Greeks, unlike their modern counterparts, could hardly have been drawn to this small island so far from their homes in search of good wine and sandy beaches. Therein lies the main question dividing modern archaeologists and historians: What were the motives which first led the Greeks to come and settle on Ischia? As Pithekoussai was their earliest colonial venture, the answer is not merely of local interest, but bears on the origins of Greek expansion to the West.

Some scholars contend that the Greeks were driven westward in search of new farmland by overcrowding and overpopulation at home. Pithekoussai is thus explained as an agricultural settlement founded on an off-shore island for protection from the local barbarians. But this theory is not without its difficulties, for hungry Greeks would have sought, above all, areas suitable for the cultivation of grain, and would hardly have bypassed the rich corn lands of southern Italy and Sicily in favor of a hilly volcanic island much farther away. Moreover, the cosmopolitan nature of the finds from the necropolis of San Montano rules out any thought of the colony as a simple farming community.

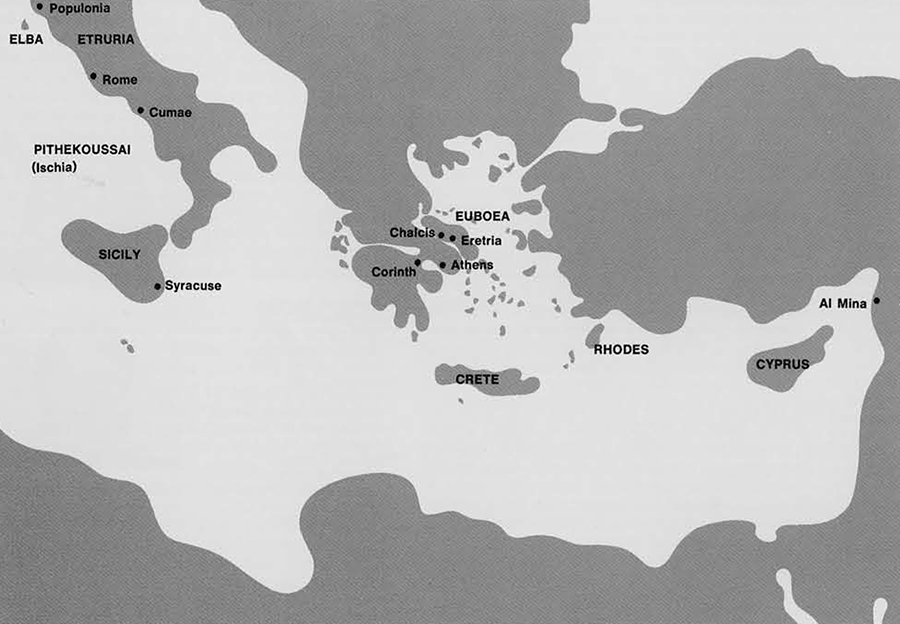

One is tempted instead to look for commercial interests in the foundation of Pithekoussai. We know, for example, that the Euboeans of Eretria and Chalcis who jointly settled the island had earlier participated in mercantile activity at Al Mina, a Greek emporium on the coast of Syria. And, further, Ischia is ideally situated for trade with the peoples of central Italy. For although good harbors are particularly rare along the west coast of Italy, there is an excellent sheltered inlet by the acropolis of Monte Vico as well as a long beach on the opposite side. This arrangement was one especially prized by ancient sailors as it allowed them a secure landing regardless of the wind direction. The hill itself is steep and surrounded by the sea on three sides, hence easily defensible in an emergency. It seems likely, therefore, that the Greeks saw Pithekoussai as the northernmost port-of-call on the Tyrrhenian coast of Italy, still safely beyond the reach of a menacing native power, the Etruscan.

But what had central Italy to offer which was so attractive to Greek traders? Metals had already been suggested as a strong possibility even before there was much direct evidence, and this theory received support from scattered finds of the earlier excavations on Ischia. New discoveries of the past three seasons all but settle the matter.

Until six years ago virtually all that was known of ancient Pithekoussai resulted from excavations in the necropolis of San Montano. Dr. Buchner was convinced by the topography and surface indications that there was nothing left of the early settlement on the acropolis. A salvage dig on the slopes of the hill in 1965, under the joint sponsorship of the University Museum and the Superintendency of Antiquities of Naples, which brought to light a huge mass of unstratified fill containing much pottery of the eighth and seventh centuries B.C. only seemed to confirm that such remains were not likely to be still in place •higher up. However, this ancient “dump” did yield a certain quantity of amorphous, unworked iron as well as other unmistakable signs of metalworking: a small lump of iron ore found there has since been securely identified as originating from the island of Elba. Another piece of iron (slag?) was found in an eighth century context at the necropolis, proving that the local metal industry went back to the early days of the colony.

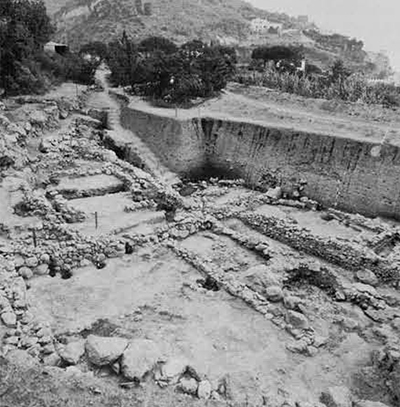

This was the situation when, in 1969, under the same sponsorship it was decided to open trial excavations on the ridge of Mezzavia, across the Valley of San Montano from the acropolis. The site lies on a series of modern terraces descending toward the sea between two steep, rocky peaks. It is, in effect, very much like a Greek theater, blissfully tranquil above the noisy tourist bustle of modern Lacco Ameno. Lush vineyards and a colorful tangle of wildflowers among the rocks and terrace walls enhance the natural beauty of the place. The view seems to span time as well as distance: from Cumae, just opposite, the mainland coast stretches north into the haze below the Alban Hills of Latium; on the west beyond Monte Vico, the Tyrrhenian Sea spreads out to the horizon.

The loveliness of this spot was somewhat marred in the summer of 1969 when vines were uprooted and the ground cleared for an initial test trench, but this was soon justified by the exciting results. Eighth century house walls were struck almost immediately and by the end of the first season two complete structures had been uncovered, as well as enough evidence to show that the settlement extended in all directions.

But, especially in the northern and eastern parts of the site where we wanted to expand the excavation, the ancient remains were overlain by a deep fill resulting from terracing in modern times. It was therefore decided in 1970 to use a small bulldozer to remove the upper three meters or so of earth, while workmen helped the machine operator to keep the scarps even and allow a minimum of debris to fall into the previously excavated area. The operation was a great success. Strict precautions prevented any damage to the site and it was estimated that the bulldozer accomplished in two days what it would have taken our workmen alone a full month to dig. Two more complete structures were excavated that year. Finally, in the 1970 summer season, one more building had been cleared as well as parts of three others.

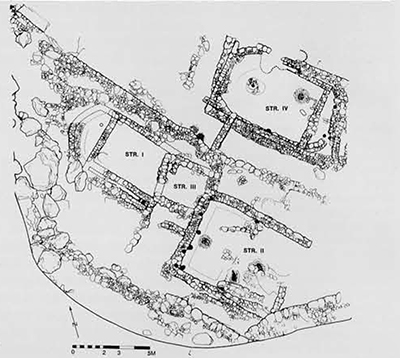

The plan shows that the site is so far composed of three ancient terraces running southeast to northwest. Of the buildings on the uppermost terrace there is unfortunately no trace because of its close proximity to the modern surface, but on the other two, one is struck by the remarkable diversity of architectural forms. Apsidal Structure is partially overlain by square Structure II, which n turn abuts against a third building of “megaron” plan (rectangular, entrance on a short side, with central hearth). On the lower terrace, Structure V went through a number of building periods of which the earliest is oval and the latest rectanguar. All these shapes occur, moreover, within the elatively short span of 50 to 75 years during which the site was initially inhabited; much of the same area was briefly reoccupied in the sixth :entury, but this will not concern us here. Strucure I, the original phases of IV and probably III, were all built in the third quarter of the eighth century, probably near 750 B.C., while the entire .ite seems to have been deserted early in the seventh century. Here, as at other Greek sites of roughly the same period, buildings with curving walls are gradually superseded by others of recilinear plan. At Pithekoussai the process would appear to have been complete by about 700 B.C., when the last phase of Structure IV began.

Unworked boulders of the local lava stone formed the standard building material on this volcanic island; mud brick was known but seemingly not used here for walls. Construction itself was generally haphazard, although occasionally a system of inner and outer wall faces with a rubble fill between may be noticed. Sometimes, too, wooden posts were incorporated among the stones for added strength (as well as to support the roof beams), but even this measure seems to have been largely ineffective against the frequent earthquakes which must have shaken the island. These were so common that in ancient times the monster Typhon was thought to lie imprisoned beneath Pithekoussai, causing it to shudder with his ceaseless struggle.

The western corner of the site was no doubt particularly vulnerable to destruction from great boulders crashing down the craggy rise above it. Thus Structure I was the only building to show signs of sudden and unexpected collapse. More or less complete vases lay crushed on its floor; it was never subsequently reoccupied. Fallen-down walls elsewhere and constant rebuilding are the sad reminders of harsh natural conditions which, according to one ancient source, drove away many of the original colonists.

Such well-preserved Greek buildings of the eighth century B.C., especially in Italy, would have been reason enough for an archaeologist’s satisfaction, but it soon became apparent that these were not all simply private dwellings. Large and small chunks of raw iron “bloom,” fragments of broken implements and nodules of vitreous slag seemed to occur everywhere in great abundance. What is more, certain features of the buildings themselves could be explained only as installations for metalworking. Gradually the evidence began to mount that this had been an area of the ancient settlement almost exclusively given over to the processing and manufacture of metal objects.

Structure III was the easiest to recognize as a metalworking establishment and was quickly dubbed the blacksmith’s shop.” It was apparently roofed only in its western half during the initial period of occupation, while a heavily burned area covered the center of an open forecourt at the east. Later, it may have been entirely open to the sky, for a hearth of large pieces of coarse pottery vessels was built near its west wall. These sherds had clearly been burnt with a heat so intense and concentrated as to have required the use of a bellows of some sort. Both floors, moreover, yielded countless small fragments of iron and slag and were themselves covered with minute spots of reddish rust discoloration—doubtless from the sparks generated by the smith’s hammering!

Structure IV had two large whetstones of imported sandstone on the floor of its middle phase and a mud-brick hearth or oven nearby at the next higher level. This latter we came to recognize as a smith’s forge, while the two smooth, flat-topped boulders of very hard, bluish stone on the floor beside it were clearly anvils. Evidence that this building saw the working of other metals as well as iron came from the debris dumped outside during its occupation. Here were found numerous snippets of bronze sheets and wire, several lumps of lead, a fragment of a bronze ingot and finally an unfinished “miscast” bronze fibula. Not far away, but in a less certain context, lay a small, disc-shaped weight of bronze and lead which, at 8.79 grams, is virtually identical to the Euboean stater as known from its coinage. A preliminary investigation shows that some of the jewelry found in late eighth and early seventh century tombs at Ischia and Cumae was made from electrum weighed out on the same standard.

Structure II and the fill outside it were also extraordinarily rich in metal finds. In fact. only apsidal Structure I provided no firm evidence for metalworking but seems. instead, to have been strictly a private house. Yet it was never rebuilt after its destruction at about 720 B.C. There seems to be ample justification, then, for calling this part of the ancient town “a metalworking quarter.” Even its location on an outlying ridge is in perfect accord with the little we know of metallurgy at this period. Early smiths required great amounts of wood for charcoal and would logically have worked outside the main settlement to be near their supply of fuel as well as to take advantage of stronger breezes to fan their fires. In this way, also, the danger of a destructive conflagration within the town would be reduced (this is apparently why ancient potters’ quarters were often “suburban”). When the eighth century Greek poet Hesiod speaks of “the softening of iron in glowing mountain fires,” therefore, he may well have had in mind an establishment something like ours.

Scientific study of the metallurgical finds has hardly begun at the time of this writing, but it is sure to throw much new light on early Greek technology. Meanwhile, the excavation has surpassed all expectations in other respects as well.

The yield of pottery has been especially abundant and, because the distribution of types and decoration varies much from one site to the other, it supplements in a fundamental way what was already known from the necropolis. Small aryballoi or perfume flasks, for instance, so common in the graves, are practically unknown at the habitation, whereas fragments of larger and more elaborately decorated vases occur in far greater numbers on Mezzavia (and Monte Vico) than in the cemetery. An entire local school of figured painting is gradually emerging from these excavations, and it promises to add a great deal to our knowledge of Greek art of the “Geometric period.” One should logically expect, for example, that vase painting on Ischia is a close reflection of the little-known art of its mother cities, Chalcis and Eretria. If this is so, many of our previous concepts will have to be modified. At the very least, some of the pottery currently attributed to the Cycladic Islands will have to be re-assigned to Euboea.

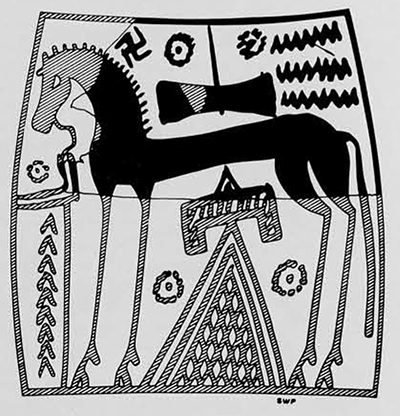

Much of the more pedestrian local work closely imitates the neat, unimaginative style of Corinth, but it is clear that the influence of Attic Geometric painting was equally important: a fragmentary amphora with a file of warriors carrying spears and shields could easily have been mistaken for the product of an Athenian workshop, although its clay marks it as local. A not very dissimilar vase from Eretria has long been considered an Attic work, but might now be attributed instead to Euboea where it was found. Other vessels from Mezzavia are decorated in a style reminiscent of Argive Geometric painting. A good example is the krater found in the back room of Structure I, with its uncomplicated but pleasing scheme of panels.

Despite obvious borrowing from the contemporary painting of other Geometric schools, however, much Pithekoussan work is marked by a unity of conception and execution which might well suggest the output of a small group of artists in perhaps a single workshop during the second half of the eighth century B.C. A chance find puts us in more intimate contact with one of these painters, perhaps the master himself, than has ever before been possible in so early an epoch of Greek art. One small sherd preserves a few precious letters of a painted inscription, incomplete and much worn, which reads in retrograde: “(… ) inos made me”—the artist’s signature! Little can be said about the painting itself from this and the few other fragments of the same krater that have turned up so far. The layout and filling ornament seem consonant with the rest of the local figured style, although the portrayal of the siren or sphinx (?) with frontal face is as yet unique on a Geometric vase. In any case, one eagerly awaits the possible discovery of a joining sherd so that this Geometric master can be called by his full name.

Aside from these rather spectacular local figured vases, the site has also produced the normal array of imports we have come to expect on Ischia: kraters, pitchers and drinking cups from Corinth, cups and small jugs from Rhodes and Euboea, oil amphoras from Athens, wine (?) jars from Palestine, together with a few Punic vases and some products of the indigenous people of central Italy. These are, we think, clear indications of the thriving commercial network of which Ischia was a vital part. What could the Pithekoussans have exported in return for these foreign goods but the metal products we now know were manufactured in great numbers within the excavated area?

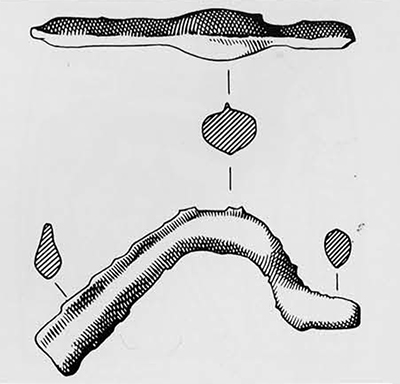

This brings us back to the question posed earlier. There is no ore naturally occurring on Ischia, nor have our explorations turned up any traces of large-scale smelting operations here. It seems likely, instead, that raw metal was imported from outside, ready for secondary working at Pithekoussai. The obvious source is central Italy, where the island of Elba and the Etruscan port of Populonia just opposite were noted in antiquity for their metal industry. A passage from the historian, Diodorus of Sicily, describes a commerce in iron, albeit at a later date, which is exactly like the eighth century trade we envision. Local people on Elba mine, crush and smelt the ore until it forms “pieces of moderate size which are in appearance like large sponges.” These lumps of iron “bloom” are then bought by merchants and shipped south to the area of Pozzuoli (on the mainland across from Ischia) or other emporia, where they are fashioned into implements which are exported to “a large part of the inhabited world.”

Corinthian kotyle with Geometric water bird.

There can be little serious doubt that it was such commercial possibilities which first attracted the Greeks to Italy. Since the actual sources of the metal were already under firm native control when the Greeks began to arrive in numbers, they settled instead at a convenient but safe distance. The men who led the colonists westward no doubt had previous mercantile experience in the Levant and elsewhere. These, Strabo tells us, were members of the Euboean aristocracy called Hippobotai, or “Horse-Raisers.” May we not see in the panels of the illustrated krater as well as on numerous other Pithekoussan vases a suitable coat of arms for these ancient knights of commerce as well as warfare? They and the other settlers of Pithekoussai were the first arrivals of that great wave of colonization which brought Hellenic civilization west and eventually turned southern Italy and Sicily into “Greater Greece.”