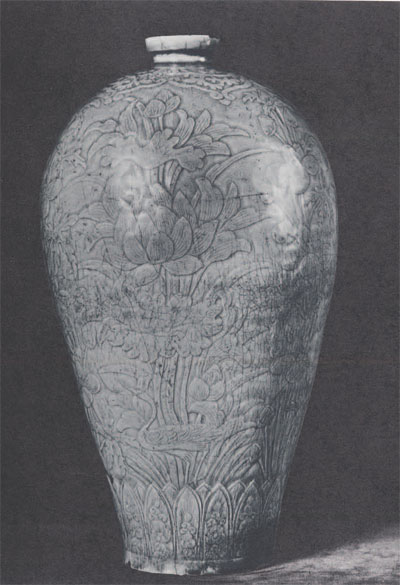

Since 1916 a most unusual celadon vase has been in the Museum’s collection. Bought through Joseph Duveen at the time he was liquidating the Morgan collection of Chinese porcelain, it is an outstanding example of the Oriental potters’ art.

Since 1916 a most unusual celadon vase has been in the Museum’s collection. Bought through Joseph Duveen at the time he was liquidating the Morgan collection of Chinese porcelain, it is an outstanding example of the Oriental potters’ art.

When, in 1911, the second volume of Mr. J.P. Morgan’s privately printed and most opulent catalogue of his collection appeared, this vase was described in Part Two of this volume as:

“TALL CELADON GALLIPOT in which the bluish trend in the hue of the glaze has prevailed over the green.

No. 1438. Over the entire body are drawn and modelled lotus flowers, grasses and ferns, and among them are three feeding storks. This vase, by reason of its color and the lavish decoration is unique. YUAN (1280-1367.) (Plate CXLVIII) Height 16 inches.”

We know that the pieces listed in this second portion of the catalogue were purchased by Mr. Morgan between 1905 and 1910. Mr. Edward Laffan, who unfortunately did not live to finish the catalogue which he had set out to complete, must, at the time of his death, have felt that this piece had been made in China. Such a conclusion was not at all unreasonable, for it has been positively established that the Korean potters of the Koryo period (A.D. 935-1392) must have had contact with their Chinese confreres working to the South in Honan province. Certainly the beautiful soft green glaze, developed by the use of iron oxide fired in a reducing atmosphere, was first produced in China. The decorative technique of incising a bold pattern in the biscuit before glazing was also a Chinese innovation. However, the Museum records show that when it was first catalogued in Philadelphia it was rightly called Korean and dated in the 10th century. This date I feel to be a bit sanguine and, in the light of present knowledge, it is most probably that the vase was made in the 12th century.

May I enlarge slightly upon Mr. Laffan’s fifty-year-old description. The vase measures 16 inches in height and 9 inches at the widest diameter of the gracefully rounded shoulder. It is covered with a beautiful pale, bluish-green glaze, except on the foot ring, which is bare, and on the base where the glaze was applied unevenly. The exposed body had fired a brownish red, probably due to the iron content of the clay. No bits of adherent clay spurs can be seen on the foot rim.

On the exterior, the incised decoration begins at the base of the short neck. On the sloping shoulder a six-lobed collar-like design of scrolled leaf forms leads the eye down to the main decoration which consists of three alternating clusters of lotus flowers, buds and foliage and three clumps of mallow flowers, buds and foliage. A small, probably white, heroin is poised on one leg before each lotus cluster. As a lower framing border, the decorator has incised a row of lotus petals, each alternate full petal being filled with what resembles a fungus with scrolled leaves above and below.

What more appropriate assemblage of flora and fauna could the artist have chosen, perhaps to show, through a glass greenly, a finny creature’s impression of his Korean marshlands? For such flowers and birds still can be found there.

Unfortunately, present knowledge of Korean art still leaves a great deal to supposition and certainly fifty years ago it was very limited. The term celadon is a western one, believed to have been inspired in France of the 17th century by the pale green costume worn by a shepherd named Celadon in the stage production of D’Urfe’s romance, L’Astree. The Chinese and Koreans generally named their ceramic wares after their kiln sites. As far as we know now, the earliest Western reference to this pale green glazed stoneware appears in Life in Corea, a book written in 1888 by her Majesty’s Vice Consul in ‘Corea,’ W.R. Carles, F.R.G.S., who, in his most perpspicacious account of the then “newly opened country,” mentions in his description of the old capital of “Song-do” as “the place of manufacture of the best Corean pottery” the fact that he “succeeded in purchasing a few pieces, part of a set of thirty-six, which were said to have been taken out of some large grave near Song-do [present Kaesong, northwest of Seoul]. These are for the most part celadon ware, glazed, with a pattern running underneath the glaze. As described by a gentleman who examined them carefully, the main patterns appear to be engraved upon the clay as fine grooves or scratches, and the subsequently applied glaze is put on so thickly as to obliterate the grooves and produce an even surface. They are made of an opaque clay of a light reddish colour, and appear, as usual with Oriental fictile ware, to have been supported in the kiln on three supports, and the supports used in several instances, at least, have been small fragments of opaque quartz, portions of which still adhere to some of them.”

Here is the first written evidence of tomb looting which became so common in the last decade of the 19th century and after the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-1905. Many royal tombs of the Koryo period were located outside of the old capital, and grave robbers, fully aware of the custom of burying personal treasures with the deceased, surreptitiously “dug for treasures.” Naturally they were loath to divulge their sources of supply and so, until Japanese archaeologists excavated some tombs and nine kiln sites, knowledge was terribly sketchy. We still have much to learn but we do know that most of this beautiful ware now preserved in western collections has come from tombs. This explains its amazing state of preservation.

We know that Mr. Carles returned eventually to England with his collection and must suppose that in time it was dispersed. So far, however, it has been impossible to trace any of these pieces, and even now I may only suggest that this extremely fine example may have been one of the pieces from the looted tomb. Its quality is certainly Imperial.