For over twenty years a clay model of a three-story structure has stood with little notice among green-glazed ceramic tombwares in a case in the Chinese Rotunda of the University of Pennsylvania Museum. Its label simply states, “Model of a two [sic] -story house. The detail and size make it probable that it is from the tomb of a wealthy landowner.” However, the label does not do justice to the importance of this artifact which is extraordinary for its architectural beauty, type of structure, and ornamentation. It is an outstanding example of Han Dynasty (206 BC—AD 221) funerary ceramic ware and gives us some of the earliest evidence for traditional Chinese architecture.

Prior to the Han Dynasty, China was an agriculturally based feudal society which had been plagued for several centuries by warfare. It was unified during the brief monarchy of the Qin Dynasty, and with the following Han Dynasty, the borders were expanded and Chinese influence was extended into Central Asia and to the south. Trade and commerce flourished and foreign ideas spread along the trade routes. Buddhism was introduced, and there was also a revival of Confucian values and an emphasis on education. Thus the Qin and Han Dynasties marked a dramatic break with the past, and the initiation of a more socially mobile, affluent, and educationally diverse society.

Changes in funerary goods—items the deceased would need in the afterlife—also occurred, as tombs were built not only by the nobility but also by people of lesser degrees of wealth and social standing. These items ranged from mass-produced figurines to finely crafted works of art; an individual’s official rank determined the size, number, material, and quality of his grave goods.

The tomb furnishings often mimicked objects from everyday life, such as houses, agricultural tools, and the like. Together with literary evidence, the tomb house models provide much of the very limited information about Chinese architecture from this early period. No original architectural structures exist. So not only do Han funerary goods reflect the society of early China and beliefs in an afterlife, but they also represent the technology and architecture of the period.

THE HISTORY OF THE MUSEUM’S MODEL

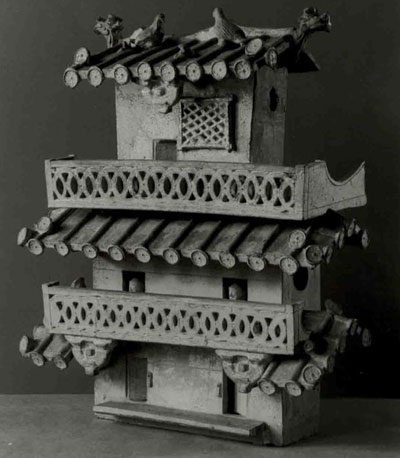

The Museum’s grand three-story model (Fig. I) is an idyllic representation of a Han-dynasty building, and was placed in a tomb to be used for eternity by the tomb occupant. Its architectural power reflects the prestige of this person. The glazed terracotta shimmers with an otherworldly, silvery green iridescence. Two serene human figures peer out over the edge of the second-story balcony, and sparrows and doves perch on the roof.

Carl W. Bishop, Assistant Curator of the Oriental Section at the University of Pennsylvania Museum, first came upon the Han model in 1915 in Japan. In a letter to the Museum’s Director, G.B. Gordon, he wrote of his excitement upon seeing this unique artifact at the home of Yamanaka, a dealer in Chinese art, and cited a model in Charles Freer’s collection (see Fig. 5) as the only piece comparable. The model Bishop so admired was shipped to Yamanaka’s New York office and the Museum acquired it April 25th, 1915. No information on the origins or date of this piece were passed on by the dealer. Other multistoried Han tomb models have come into museum collections since—with little or no provenience information—through dealers and collectors or come to light through excavations; however, the Museum’s model is still a unique architectural example.

Restoration prior to its purchase by the Museum did not diminish the model’s handsome proportions and architectural beauty. The right side of the upper floor must have suffered significant damage and was extensively repaired, creating a new effect. The remaining portion of the third floor, which would originally have been the width of the lower floors, was centered at the top. The dragon-head extensions in a darker green glaze that were glued to the ends of the third story roof were probably not part of the original structure. The two large birds nearest the ridge of the roof were joined with glue to the house. They may not have been placed here initially. There is Less evidence of repair work on the pair of smaller birds. A bracket arm which was attached at the new “center” of the third floor roof has been lost. However it is visible in early photographs (Fig. 2) and appears to closely match the bracket sets on the lower floor and may have been part of a related structure from the same tomb which no longer survives (see below).

HAN TOMB MODELS

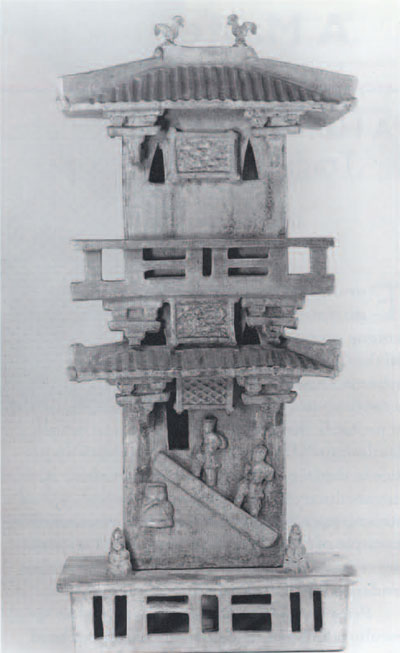

Many different types of buildings were created for Han tombs, and great variety occurs among the walled compounds with gates, watchtowers, storage buildings, living spaces. and inner courtyards. For example, multistoried buildings (occasionally graced with figures carrying sacks) that are believed to be granaries or storage towers have been found (Fig. 3), as well as a number of tall, airy towers with moats at the base and populated with multiple figures (Fig. 5), As a single building the Museum’s model has no prototype. It was most likely a part of a complex of buildings representing the estate of the tomb occupant. The most compelling evidence for this is the lost bracket which had been attached to the top roof. It appears to be contemporary but did not fit on any section of the surviving model. Also, a platform at the bottom front might make more sense if additional pieces or buildings were still extant. The unglazed bottom section below the platform would have been less conspicuous with a surrounding wall or hidden if slotted into another piece. The other structures may have been destroyed just as the side wall of the model was. The existing structure may have served as a watch tower, storage building. or house within the complex, and its figures may have represented either watchmen, servants, or even portraits of the husband and wife who occupied the tomb from which the model came.

The ornamentation of the Museum’s model is unusual. The overlapping circular pattern on the balcony is not found on other known examples. The teardrop shape of the windows on the sides of the building is also distinctive. Typically, the cut-out openings on models include rectangles. squares, and circles.

The University Museum’s model is an ideal example of Han ceramic technology. Red clay fired to earthenware hardness was typical for funerary wares. The building was shaped and pieced together by hand and surface details were incised. Molds or stamps were used to make the two human figures and the ornamental tile ends on the roof. A dark green lead glaze was applied prior to firing. This type of glaze originated around the 1st century BC, during the late middle Western Han period, in Shaanxi Province or Loyang in Henan Province. The color, created by the addition of copper oxide, became increasingly popular throughout northern China during the Eastern Han period (AD 25-220). Due to exposure to moisture during burial the glaze on our model has decomposed to a silvery green iridescence.

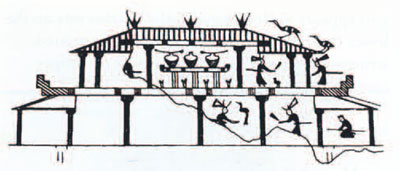

The house, together with other funerary clay models, stone reliefs, tomb paintings, and architectural fragments from the Han Dynasty, gives a chronological framework for the early develqpment of several features characteristic of traditional Chinese architecture. Similar circular tile ends with scrolling motifs appear on excavated tiles from the Eastern Zhou (771-256 BC). Qin (221-207 BO, and Han dynasties (Fig. 1). The earliest evidence of wood-framed structures appears in representations incised on bronzes of the Warring States period (4.03-221 BC) (Fig. 6); however, the Museum’s Han model more clearly demonstrates the features of the wood frame. Buildings with three or more stories appear for the first time in Han tomb models such as ours. Wooden beams rendered in clay extend from the lower wall. Brackets, a combination of arms and blocks used to transfer the weight of the roof to a column or tie-beam in wooden construction, are shown in detail. Han brackets were limited to a single step or tier extending outward from the building. The straight gable roof with overhanging eaves was a common Han type. Balconies and lattice windows, features which first appear in the funerary arts during the Han dynasty, are evident on the Museum’s model. Thus many essential features of traditional Chinese architecture are preserved for the first time in three-dimensional form on the model, including the use of a column and beam framework, supporting bracket sets, gabled roofs, tiled roofs with circular tile ends, and lattice windows.

The Han model house, a masterpiece in clay, represents the worldly achievements of an individual but is as well an early and important example of the ceramic traditions and architectural achievements of Han China.