The excavations at Porto Cheli (ancient Halieis) are part of the Argolid Exploration Project of the University of Pennsylvania, under the direction of Michael H. Jameson, Professor of Classical Studies. The author of this article, John H. Young, served as Field Director in 1962. – Editor

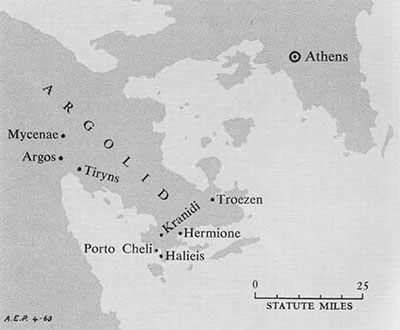

The easternmost peninsula of the Peloponnese, called the Argolid, contained many of the most ancient and powerful cities of Greece. Argos, for which the region is named, was at the dawn of history mistress of this land. Before this, in the age described by Homer, the nearby city of Mycenae was mightier still, and her rulers–the House of Atreus–held primacy over all Greece. Yet earlier still, before history and before Homer, the city of Tiryns must have been predominant. This is at least suggested in Greek mythology, which makes the greatest of Greek heroes, Heracles, born of a Tirynthian king, Amphitryon, and a Tirynthian queen, Alcmene. Excavation, too, hints at early greatness; for below the Mycenean palace German excavation disclosed traces of a huge circular structure, built in the Early Bronze Age.

Argos gained nominal control of both Mycenae and Tiryns in historic times, and finally attacked and subjugated them at some time in the early fifth century B.C., reducing them to dependent villages. What happened to Mycenae thereafter we hardly know, although recent excavations have revealed plentiful remains of Hellenistic times. At Tiryns we know that much of the populace fled, to settle in the southern Argolid at a place called Halieis. We have scattered references to these refugees and their new home from Herodotus, Thucydides, Strabo, Pausanias, and the lexicographers. but all combined they tell us tantalizingly little, not even enough to locate with certainty the new city.

A new source of evidence was tapped by the Greek numismatist, Svoronos. In a study published in 1907 he collected all the known examples of a rare issue of Tirynthian coins of the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. The earliest, showing the head of a goddess, were uninscribed. They are followed by a brief series with the head and club of Heracles, some bearing the inscription TIRYNTHION–of the people of Tiryns–, and then by a long series displaying the head of Apollo and on the reverse a date palm, always with part or all of the same inscription. It had been believed that these coins were struck at Tiryns by those who did not emigrate, but Svoronos demonstrated that the only known examples for which a provenience could be established were not from Tiryns at all, but from a hoard, found long before at a site described laconically as “an hour and a half from Kranidi.” Kranidi is a modern town at the extreme south of the Argive peninsula; searching for a likely site, an hour and a half by mule or donkey, Svoronos concluded that the ruins visible near the modern village of Porto Cheli, almost at the southernmost tip of the peninsula, were the most likely source of these coins, and could then only represent Halieis, the home of the Tirynthian exiles.

Professor Michael Jameson of the University of Pennsylvania has in recent years been studying the sites of the southern Argolid–including Troezen and Hermione–and became interested in the site at Porto Cheli; the probability that it was in fact the ancient Halieis seemed increasingly strong to him.

But if some facts were known (or could be surmised) about this city of Tirynthian exiles, many more were unknown, lost from the pages of history. Even the location of ancient Halieis was in doubt; the site at Porto Cheli seemed to fit the requirements neatly enough, but the proof was needed. The coins and other meager evidence gave some hints of the cults of the town, but its political organization was wholly obscure. There was even less evidence at hand for the vital problem of chronology: the date of the exile from Tiryns and the founding of Halieis has been put variously in the 470’s, at 470, in the 460’s and so forth and, in fact, by one authority at 300 B.C. As to how long it had been inhabited, we could say for certain only that it was deserted when Pausanias passed by in the early second century A.D. The answers to these questions might never be found, but there remained one way to seek them out: excavation.

Accordingly, Dr. Jameson began to plan trial excavations for the summer of 1962. Private donations for this purpose were made to the University of Pennsylvania, and these funds were supplemented by grants from the National Science Foundation and the American Philosophical Society. Mr. Charles K. Williams, a graduate student at Pennsylvania, served as Architect and I was invited to join the staff as Field Director. Thomas Jacobson and Michael Cheilik served as additional excavators, and other students at Pennsylvania helped in various ways. The work was carried out under the aegis of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, while Dr. Nicholas Verdelis, Ephor of the Argolid, gave unstingingly of his aid and counsel. After preliminary negotiations and assembling of staff and supplies, we began excavations on August 6.

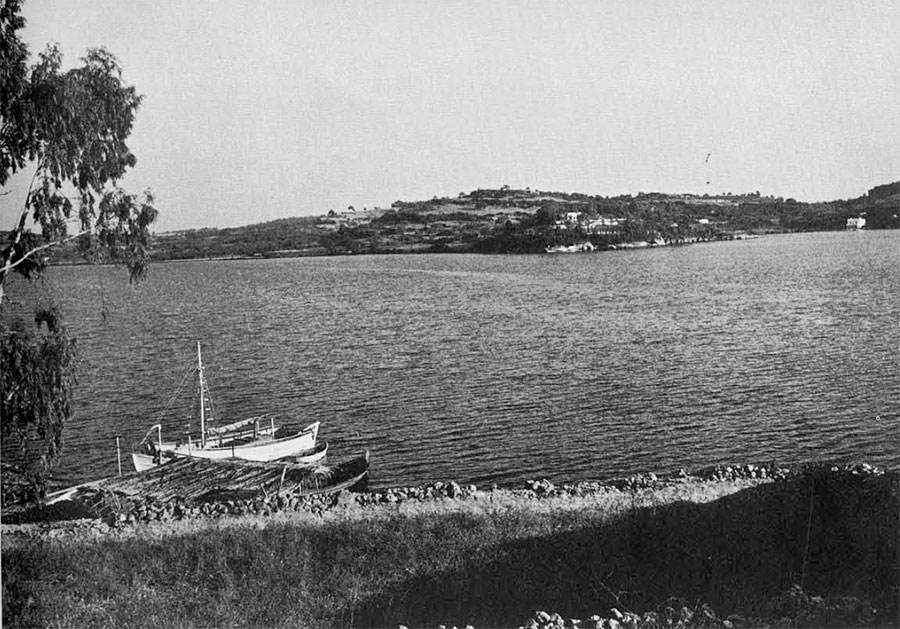

Modern Greek villages fall by their aspects into two groups: the inland kind, its grey stone and tan brick melting into the dun-colored landscape; and the island kind, with white houses gleaming in the sun as though to challenge the blinding glitter of the sea before them. Porto Cheli is of the latter kind. Its houses stud the hillside above the quay and lie reflected in the sea below. The harbor has only a narrow entrance, so that once inside one feels as if one were sailing on an inland lake. This secret quality may well have led the Tirynthian refugees to it; even after entering the harbor one must proceed some way before the location of the ancient city is visible. One of the first tasks which must have engaged settlers was to build a fortified circuit wall surrounding their new home. The foundations of this wall are still to be seen, and had earlier been studied by Dr. Verdelis, and drawn by Mr. Williams, so that they bounded our prospective site nicely for us.

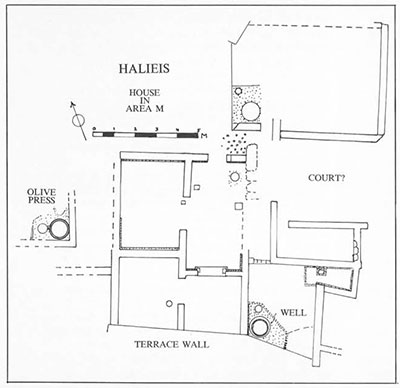

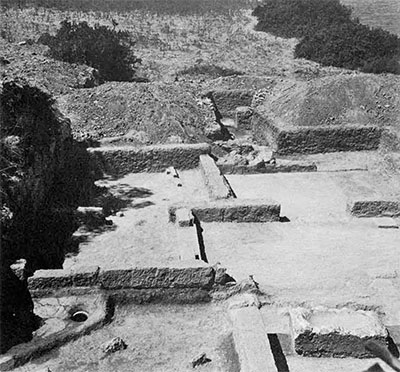

We chose four areas for excavation: two near the sea and two on the higher land. One of the shore sites (Area M) is at a point about halfway between the wings of the fortification wall which descend to the sea to east and to west; the others were all near the wall itself: one close to the point where the eastern wing reached the sea (Area T), another on a high spur of land just within the east wing (Area C), and the last at the very highest point–our “Acropolis,” at the joint of the two wings and about fifty meters above sea level. We shall now briefly consider our discoveries in these areas, following this order.

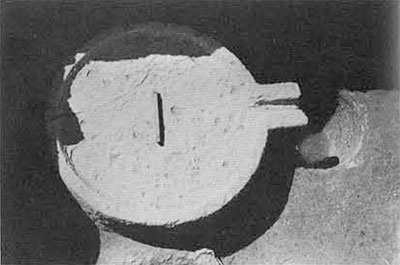

The excavations at Area M were supervised by Mr. Cheilik. At the north was the sea, at the south was a very heavy ashlar terrace wall. Here he cleared a house, built against this wall and thus later than it. I shall not describe it here, but we must at least notice a few of the finds. In one room several Corinthian (or Pseudo-Corinthian) cups were found on the floor, almost intact; their shapes (they are skyphoi) lead one to date them no later than the fifth century, and indeed the early half of the fifth century seems preferable. Again, directly outside the house proper, in an outbuilding, we found the heavy stone base of an olive press and, sunken in the floor below its spout, was a jar to catch the oil. In it were two fragmentary jugs which could only have been left there when the press (at least) fell into disuse.

Neither jug appears to be later than the fourth century, and this should give us some idea of when the house, too, was abandoned. One of the rooms was certainly a kitchen, with a hearth in one corner, in another a cement platform in which was set a heavy terracotta well-head, and before it a jar, apparently to take the drip. Thinking this to be the mouth of a cistern, we set to clear it out, but it was so close to sea level that it soon filled with water. We thus gave it up, but after a time, when the earth had settled and the water cleared, we observed to our astonishment that some of the workmen were drinking from it. Indeed, it was an ancient well, found here in a parched land which was called even by the ancient poets “thirsty Argos.”

Two building complexes were partly cleared in Area T under the supervision of Mr. Jacobson. One again was apparently a house, but this was a very large and luxurious building compared with that in Area M. Especially notable is the splendid banqueting hall, with cement floor in perfect condition, a slightly raised platform at the sides to support the dining couches, set off from the central area by a carefully executed molding. The walls were plastered, and painted white over a red dado. Opposite the door were the remains of a stuccoed structure (painted yellow) which may have been an altar, and at one corner of the room a narrow drain cut through the platform to lead out under the wall. This would not only be useful to those who sluiced out the room after a party, but would also, during the party, carry off the wine spilled during the after-dinner, wine-flinging game of kottabos.

The second building is of a different nature. It is roughly square in shape, its interior a single large room. The sloping tiled roof was supported by a single central column or pier, for which we found the base. The entrance was from the inland side, and here there were apparently two doors, perhaps with a column between them. This building must have served some political purpose: meetings of a council seems the most likely. To be connected with it are an Ionic capital of unusual design and a fine anta capital. Also in Area T a deposit of Attic red-figure sherds, some fine, was found. Perhaps they are the debris of the very drinking vessels used in the banqueting hall. Elsewhere, a mass of small votive cups, together with a fine fifth century female figurine, attests to the existence of a sanctuary, presumable of a goddess, in the neighborhood.

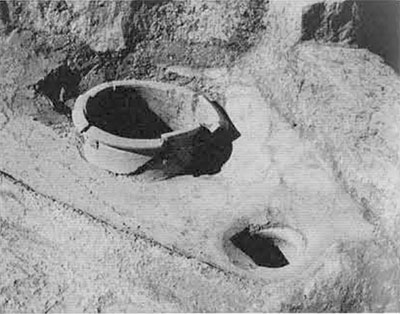

Dr. Jameson supervised the excavation of Area C, which belonged to the industrial district of the town. Three buildings were disclosed: one oblong, divided into two rooms only, which seems to have served as a storeroom and perhaps also a shop; a second has the general plan of a modest house but from the quantities of lead found in it, seems to have been at least partly used as a workshop. The third building is the most unusual; one room, paved with fine cement, was certainly a dye works. Three deep circular basins are sunk in the floor, another round area is only slightly lower than the surface, and from it a drain runs into one of the basins, while in the corner of the room are two cuttings and a shallow depression, certainly evidence of a press. Other rooms contain fragments of huge clay jars which perhaps served as dye vats or water tanks.

Quantities of loomweights found in the neighborhood further emphasize the importance of the textile industry in this area. One weight, of pyramidal shape, is of lead and bears a two-letter inscription pricked into the lead with a pin. The dye works is conspicuously built of much re-used material: for instance, a carefully cut block, with cavetto molding placed upside down, forms a step, and a handsome re-used anta capital was also found here. We may say, then, that this building must be late in the history of the town. How late is perhaps indicated by a fine silver tetradrachm of Alexander the Great which Dr. Jameson found in the building. It is of the dated Phoenician series, and was struck at Sidon before October, 323 B.C.

We have noted that the fortification wall passes close to this area. Hitherto unsuspected were the foundations of a semicircular tower which jutted out from its circuit; it was cleared by Dr. Jameson.

Mr. Williams, who supervised the work on the Acropolis, also concerned himself with the fortress wall. His studies revealed two, perhaps three, phases of its history, and his skill as an excavator was proved by the large area of the mud-brick superstructure he laid bare for study. Here too the presence of a semicircular tower, larger than the lower one, was revealed.

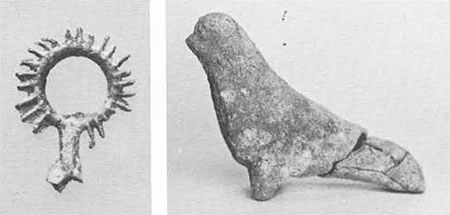

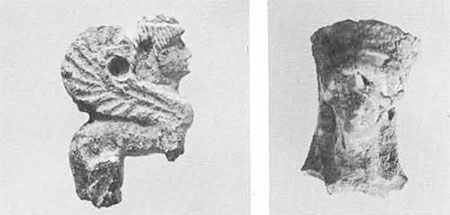

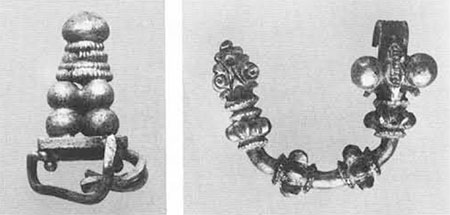

But another trench on the Acropolis proved to be the most exciting. Close to the very highest point of land, within the circuit of the wall, were discovered parts of a building, and outside it two bases for altars and perhaps a statue plinth. In the soil around them, particularly by the statue, was a large deposit of votive gifts, proving beyond doubt that this was an important cult place, and giving our expedition its most unexpected finds. The offerings were of various types: miniature cups, terracotta figurines of women and of horsemen, bronze arrowheads, and, especially, jewelry.

Jewelry is not often found except in tombs; so let us pause a moment to consider it. First, there are many pins, the pin itself always of iron and only the head of bronze–or sometimes of silver. Most commonly the head is rendered as a pomegranate, but there are other designs, including a tiny sphinx seated upon an Ionic column capital which is a miniature masterpiece. There are also many lead circlets, the outer edges studded with minute pomegranates, each about the size of the head of our own common pin. There are many earrings, the pendant generally ending in the pomegranate form. The most beautifully worked of all the jewelry is a silver fibula with a minuscule palmette to serve as the catch. That these are al votive offerings is certain and it is almost as certain that they were dedicated not to a god, but to a goddess. To the problem of the identity of this goddess we shall return.

I have now set forth very broadly what we found. Needless to say, much study must be devoted to all these discoveries before we can truly assess their meaning and their value. But the main outlines, I think, are already clear.

Let us consider, then, (a) how many of our original questions can now be answered, (b) which questions are still unanswerable, and (c) what new questions have been posed. In the first place, can we now prove that our site is indeed Halieis, the city of the Tirynthian refugees? Since we found almost no inscriptions, we are lucky to be able to answer: Yes, we are certain. In all four areas bronze coins were found, here and there, where they were dropped in antiquity. There are nineteen in all, and of these eleven are certainly Tirynthian and two more may well be. Such a percentage of a rare type proves beyond any doubt that our site is the one we wanted it to be; it also proves that the series was struck not at Tiryns itself, but at Halieis, by refugees from the mother city who still regarded themselves in the fourth century B.C. as Tirynthians.

Second, what have we learned about the site itself? The two houses cleared give us some notion of private life in Halieis and show us too that some, at least, of these refugees lived comfortably and that one was in fact rich. As to the city’s public affairs we still know little, but the presence of a public building, probably a meeting place, suggests the organized government of an independent city-state. As to industry, we know that textiles were important, that there were pottery works, and that agricultural produce, as we should expect, included grain, grapes, and olives. Much more is now known about the fortifications, and there are indications that they were rebuilt and strengthened more than once. This reminds us that we have literary evidence for three attacks by Athens(in 458, 430, and 425), and perhaps Mr. Williams will find that some of these were responsible for the rebuilding operations he has noted.

Fortunately among the votive objects were some terracotta figurines. These are so close, both in style and manufacture, to the figurines dedicated to Hera at Tiryns that some could well have been brought here from the mother city. We may then be certain that the major cult was, as at Tiryns, that of Hera. A lead figurine representing Heracles may indicate another Tirynthian cult here, and perhaps the second altar was for his worship.

Finally comes the problem of dating, for both the founding and the abandonment of the town. We recall that the flight from Tiryns and the relocation at Halieis have been dated variously from 480 to 300 B.C., at the two extremes. Can our new evidence help to settle this problem? I leave the precise chronology to Dr. Jameson, but meanwhile there can be no doubt that the earliest date compatible with the historical evidence will be the right one. We have both pottery and figurines which must belong to the first half of the fifth century B.C., some of which seem to belong to its very earliest years. Indeed, I should undertake to say, even now, that any date later than 470 is out of the question, and we may well take 470 (the battle of Plataea) as our terminus post quem.

As to the abandonment of the town, before the excavations took place, we had no evidence at all except that of Pausanias in the second century A.D. when he found it deserted. We can now say that so far we have not found a single object which can definitely be dated to the third century B.C.; everything seems to be earlier. Thus, when Professor George Karo estimated that our city was founded around 300 B.C. it appears that he gave us its end, rather than its beginning.

That the unoccupied site which the Tirynthians chose as their new home had been settled before, they could not have known. But our excavations on the Acropolis have uncovered traces of an Early Bronze Age village, to be dated probably in Early Helladic II, that is to say in the twenty-third to twenty-second century B.C. Mr. Jacobson will study the pottery further and perhaps narrow these chronological confines. Conversely, we now know that our site was visited long after the Tirynthians had gone. Even before excavating we observed bits of Late Roman pottery scattered on the surface. Now we can date such pottery to the fifth century A.D., and we also know what these people were doing there: they were systematically searching the ruins for usable building blocks, which they must have taken away with them for their own purposes, perhaps for the erection of a Christian basilica, whose own ruins may lie undiscovered somewhere nearby.

In sum, then, we have proved that our site is Halieis, settled by Tirynthian exiles early in the fifth century B.C., exiles who considered themselves still Tirynthians and who coined Tirynthian money and worshipped Tirynthian deities as they would have if still at Tiryns. They remained at Halieis until late in the fourth century (possibly into the third century B.C.), then vanished, who knows where. We now know something of their life, private, public, and economic, and something of at least one, possibly two of their cults. We also have new information on their fortifications. This we learned during trial excavations of short duration. But, if we know some new things, much more is still unknown. Did they build no temples in their new home? Where was the cult place of the Apollo celebrated on their coins? Again, we have found what looks like a public meeting house; did they never inscribe the minutes of their meetings on stone? We found no such inscriptions. Where was the agora of the town?

Such questions demand answers and some of the (perhaps all) can be answered by further excavation. Not so easy to answer is still another question. What happened toward the close of the fourth century to cause the site to be abandoned? There seem to be no traces of fire, which would accompany destruction at enemy hands. This is a truly puzzling problem. My only guess is that conditions in Tiryns, brought about perhaps by Alexander and his successors, made it safe for the descendants of the original Tirynthian exiles to go home. But to prove this, evidence will be needed from Tiryns itself.

In any case, we have found that elusive thing, so often sought, so rarely found, a city of the Classic Age, undisturbed right up to the present day by later building. For five weeks of excavations, I submit that this it triumph enough.