My friend Ibrahima and I are visiting a school for the visually impaired just outside Banjul, the capital of the West African country of The Gambia. Behind the rusty and partially unhinged gate of the school’s walled compound sit three yellow buildings surrounding a dusty empty courtyard. As we walk into a classroom we are greeted by a young teacher and her aide. Three students dressed in red and white shirts with matching trousers sit on a wooden bench. Ibrahima explains that I am a college professor from the United States who has returned to The Gambia after a three-year absence to continue my research on human rights in Gambian society.

My friend Ibrahima and I are visiting a school for the visually impaired just outside Banjul, the capital of the West African country of The Gambia. Behind the rusty and partially unhinged gate of the school’s walled compound sit three yellow buildings surrounding a dusty empty courtyard. As we walk into a classroom we are greeted by a young teacher and her aide. Three students dressed in red and white shirts with matching trousers sit on a wooden bench. Ibrahima explains that I am a college professor from the United States who has returned to The Gambia after a three-year absence to continue my research on human rights in Gambian society.

While we make small talk, the teacher’s aide instructs the three students in counting using strings with beads made up of different shapes and sizes. Our conversation is slow though pleasant. The hum of the fan, the soft clattering of beads from the students’ counting, and the midday heat conspire against a quick exchange of words, allowing me to look around the room. There is not much to see. Although the school receives some government support, like most Gambian schools, it is clearly not wealthy. Apart from the students’ benches, the teacher’s weathered desk, a few scattered chairs, and an old armoire in a corner are the only furnishings. On the walls, a few posters in English—the language of instruction in Gambian schools—spell out the rules as agreed to by the students and praise the importance of education and human rights.

A sharp reprimand from the teacher’s aide to a student interrupts my observations. “You’re counting the wrong way,” she shouts, yanking the string from the student. He must count from the left, not the right. As the student resumes counting, the teacher turns to me and nods her head toward him. In a loud voice she says, “This one is not very bright.”

Twenty minutes later, as we leave the school, I am still thinking about the harsh reprimand and the teacher’s comment. The episode leaves me with a somewhat bitter taste. It seemed inconsistent with the spirit, if not the letter, of the human rights the school loudly extols on its wall. Perhaps sharing my unease, Ibrahima asks me for my impression.

Worried that I might offend his hospitality, as well as the school’s, I remark simply that “it was interesting.”

In response, he explains that the notion of disabled children having rights is new in The Gambia. “People are not used to it. Give it time,” he suggests, “and they will adapt.”

Adapting To Rights: From Cultural Trait To Social Process

The notion that people will “adapt” to human rights is a curious but common one located at the heart of any human rights campaign. Consider the case of boycotting goods from a country that has violated human rights. The underlying logic is that with persistence and dedication people will understand the human rights implications of their purchases and change their ways. When it comes to globalizing the concept of human rights, although it is a slightly different kind of campaign, what still matters is getting people to change.

In places like The Gambia, government bodies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and development agencies constantly remind people about their rights by espousing a “rights-based approach” to just about everything from economic development to schooling. Their argument goes something like this: if people realize that they are entitled to certain rights, not just by virtue of their citizenship, but simply because they are human, and that there are limits to what states can legally do to them, then all kinds of social issues— from corruption to poverty to gender inequities and to violent conflict—will be ameliorated.

Yet, while this sounds well meaning, a skeptic might note that the dissemination of universal human rights—a set of ethical and moral claims—is just another instance of an external cultural imposition. How can a set of rights, defined predominantly by Western diplomats and activists, claim to be universal? Can the promotion of these rights be seen simply as an alternative way to impose Western values on other cultures?

This reasoning resonates among many Africans, who see a subtle link between European colonialism and the promulgation of human rights as a modern approach to telling Africans what to do, what to say, and what to think. This link helps explain why many Africans support the actions of Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe. Although widely condemned by human rights activists and the British and American governments for using violence, fraud, and intimidation to cling to power, many of my friends in The Gambia say that Mugabe is simply sticking up for Africans against the arrogant demands of “whites.”

Anthropology has also wrestled with the concept of human rights since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by the United Nations in 1948. At that time, the American Anthropological Association (AAA) issued an ambivalent response because the Declaration ran counter to contemporary anthropological thinking on rights and culture. Instead, the AAA argued that what one society considered just, fair, or lawful was profoundly shaped by that society’s culture. Therefore, to draw up a list of universal rights was ethnographically suspect and, more worryingly, could lead to the imposition of ostensibly universal values on cultures that did not share them. This position—often characterized as a culturally relative one and mischaracterized by non-anthropologists as a morally relative one—made it difficult for anthropologists to unequivocally commit to universal human rights. As a result, it is not surprising that for a long time anthropologists had little to say about human rights except for when they concerned specific matters of anthropological expertise such as indigenous peoples’ rights.

This changed in the early 1990s, however, when the theoretical upheavals within the (cultural) anthropology of the 1980s combined with the reinvigoration of the global human rights debate as the Cold War came to an end. To simplify: where anthropology (with a few exceptions) had previously considered cultures as fairly homogenous and static, the discipline’s emphasis now turned to how cultures were fluid and con- tested. Instead of focusing on cultural traits or the meaning of a given phenomenon (such as rights) within a given culture, the task now became to track the various ways in which particular elements of culture (such as specific rights) were constructed and transmitted through social practices. This new perspective brought power relations and the globalization of ideas, goods, and images to the foreground in anthropological discussions. In other words, part of anthropology’s mission now was to understand how “the global” was inserted into— and used by—local communities to engage in politics, define community boundaries, and allocate resources.

This reconsideration of the purpose of anthropology has significantly affected the anthropological study of human rights. Now, rather than question whether or not a given standard of human rights can be correlated to specific aspects of indigenous cultures, anthropologists focus on understanding how human rights are invoked by people in specific situations, on identifying what political and social issues are related to human rights, on determining who uses human rights to frame discussions, and on exposing what aspects of life are left out of discussions about human rights.

In other words, human rights are now seen to be a social process analogous to, say, religion. Just as an anthropologist might study a religious ritual—how it is structured, who participates, what beliefs are reinforced, and who resists these beliefs—anthropologists can examine claims about human rights to illuminate not only how and why the idea of human rights spreads across the globe but also how the increasingly widespread rhetoric of human rights affects societies. From this vantage point, whether or not human rights constitute a “foreign” cultural imposition is no more important than understanding how the idea of human rights spreads, how it interacts with other ideas, and how it shapes social identities and the lives of people.

Teaching Rights: The Gambia’s Civic Education Program

When I first arrived in The Gambia, it was this approach to human rights that was on my mind. With an academic back- ground in both anthropology and human rights law, I was not only interested in how the different cultures of The Gambia conceived of rights, but also in how people there used, debated, and critiqued the international human rights that they encountered in the media, in schools, and via the work of government organizations and NGOs.

Part of my research aimed at tracing the institutional chan- nels through which human rights spread through the country and the organizations that promoted the idea of human rights as a way to consider what is right and wrong in society. The public school system clearly emerged as a particularly impor- tant channel—a fact that would not surprise anthropologists who have long noted the importance of schools and national curricula in fostering social identities and beliefs (consider, for instance, the American Pledge of Allegiance). If a national school system can be used to foster patriotism, why not use it to promote human rights?

In 2004, during an earlier trip to The Gambia, I accompanied the National Council for Civic Education (NCCE)—a government-established non-partisan body charged with promoting an awareness of civic rights and responsibilities through town-hall meetings, radio campaigns, and other means—on one of its many school visits. The NCCE had just started a pilot project for the insertion of human rights into the primary school curriculum. The approach they adopted involved “mainstreaming” human rights into the curriculum by making every subject (including the natural sciences) have a human rights component (rather than making human rights a separate class or inserting it as a theme-of–the-week in an appropriate subject). The goal, I was told, was to let the language of rights suffuse through the learning process irrespective of the topic of the moment.

I was invited to accompany one of the NCCE’s program officers, Lamin Njie, on his visits to two schools—one in the capital Banjul and one in the small fishing town of Kartong near the border with Senegal.

From my vantage point, the Banjul visit was somewhat of a failure. We arrived during the morning break and were ushered into a crowded classroom with perhaps 50 students. One of the teachers and the school principal began by introducing Lamin and me. During the lengthy introduction, the students looked at us with interest and some muted laughter, perhaps amused and a little bit perplexed at seeing a tubab, or white foreigner, in their school. Very much to my surprise, the principal introduced me as a foreign “human rights expert” there to give a lecture. Although I did my best to give an impromptu lecture on human rights—and I like to think that I acquitted myself rather well—I was disappointed not to see the NCCE program in action.

Nonetheless, the visit suggested two important things in terms of how human rights are thought of in The Gambia. The first was the assumption that I—a white, US-based European roughly three times their age and with a dramatically different life history—would be able to tell school children about the meaning of human rights. Second, when I asked the students what the most important rights were, they immediately started talking about poverty, economic development, health, and other issues usually labeled as “socio-economic rights.” In contrast, many of my students in the U.S. mention such political rights as freedom of speech and the right to vote first. The Gambian high school students quite understandably had a rather different set of concerns than U.S. college students, and, accordingly, thought of human rights in different terms.

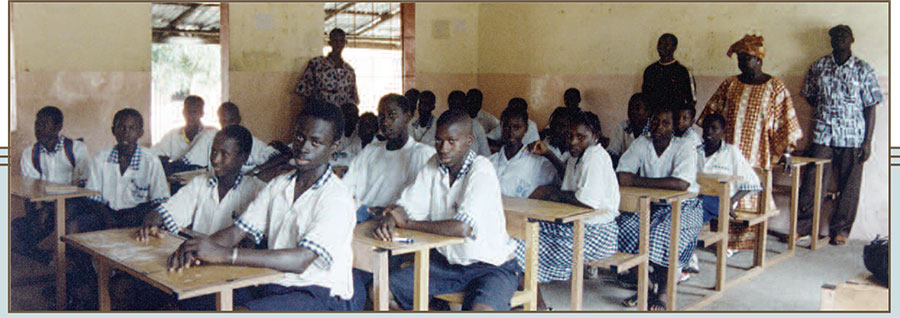

Our visit to the school in Kartong was more successful, but also contained some surprises. Upon entering the school compound, a large woman in a colorful yellow and black outfit introduced herself as the head teacher. She excitedly explained that the students were ready for us, and ushered us into a class- room slightly smaller than the one in Banjul with perhaps 20 students ranging in age from about 12 to 16. A young teacher introduced himself to us, then quickly explained to the students what we were doing there, admonishing them to be on their best behavior as they had a foreign visitor. Lamin and I sat down along the wall, and the teacher began the lesson.

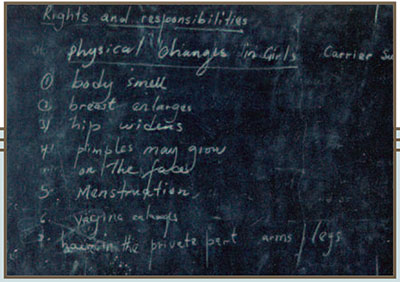

Today’s class was a biology class and the topic was rights and responsibilities with reference to sexual education. With the help of nervously snickering students, the teacher enumerated several perceived characteristics of sexual maturation in the human male and female. He asked a few students to role-play a couple of scenarios in which female students were first asked to accept the advances of the male students (resulting in the females becoming pregnant and having to end their schooling), and then they role-played rejecting the advances. Afterwards, the teacher asked the students to consider “what do you imagine can happen when there are no rules and regulations in the school?” The students’ responses were far ranging but centered on the breakdown of order and the loss of civility.

As you might imagine, I was a bit surprised by this lesson. There was no mention of human rights documents and standards—international or domestic—and no mention of legal procedures through which one can seek redress if one’s rights are violated. Instead, human rights were presented in the con- text of sexual maturation—a process framed as biological, natural, and inevitable (with an inevitability that is brushing off on the concept of human rights). In other words, rights were presented as intrinsic to how you take care of yourself and how you interact in a well-functioning society, but not as legal claims or entitlements. They were, in effect, presented as a fairly vague and hazy moral ideal of how one ought to behave, not as a tool to protect oneself from an overbearing government.

The Many Lives Of Rights In The Gambia

This difference between what we in the U.S. often think of as rights—political entitlements backed by a legal process—and what the Gambian students emphasized is pervasive in The

Gambia. Although this difference is a bit puzzling, understanding it helps explain much about contemporary Africa and The Gambia, as well as how the globalization of ideas like human rights takes place.

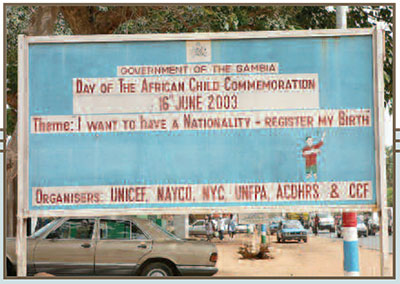

In The Gambia, I am continually struck by the dizzying diversity of invocations of human rights. An Islamic charity whose main task seemed to be organizing a marathon, for example, still thought of itself as engaged in human rights work. An electrician once suggested to me that his dismissal from a job at a local brewery was a human rights violation. A billboard on the street proclaimed that early child marriage was a human rights abuse. It is, therefore, not surprising that a journalist friend of mine told me that human rights were central today to everything in The Gambia.

In part, this results from the underdeveloped Gambian legal system and the human rights record of President Jammeh. The Gambian government has been accused of persistently violating some core political rights, such as freedom of speech, and for being slow to address women’s rights issues, such as female genital mutilation. Jammeh has been roundly critiqued for his authoritarian streak, for letting the security services operate with impunity, and, in 2006, for launching a controversial HIV/AIDS cure based on traditional medicine that lacked any scientific proof of its efficacy. Jammeh and his government responded sharply by declaring a local United Nations representative persona non grata. Most recently, he has threatened to behead homosexuals and other “undesirables.”

Even the topic of children’s rights—typically considered politically safe—has provoked the government’s ire. In the Gambian legislature, the then majority leader and close associate of Jammeh once exclaimed: “Rights, rights, rights! There are too many rights. A child of less than 12 years is a kid. He doesn’t know his left and right, he needs to be directed!” Here the majority leader was expressing a common concern voiced by Gambian adults—children’s rights make children spoiled and disobedient and give them an excuse not to work for their families.

In a way, this point of view is partly justified. For example, historians of childhood in the West have demonstrated that the concept of children having a political identity outside their families and their need for protection from economic obligations is a relatively recent one. Indeed, the current international rhetoric of children’s rights—seen, for example, in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)—has been largely promoted by northern European countries and its conception of childhood is at odds with Gambian social, cultural, and economic practice. In West African societies, childhood is not based simply on age, but rather is linked to important social and biological events such as menarche. Children are also considered part of a familial community where even young children often work in farming, fishing, or petty trading to help their family’s finances.

Taking this all into account, the government-sponsored civic education program and its emphasis on rights seems odd. How can a human rights program be framed as a matter of sexual education? Why would a government with an apparent interest in ignoring talk about human rights launch a human rights education program? Why are children’s rights promoted when in many ways they clash with local under- standings of rights? And how can rights, as it seems, be every- where and nowhere at the same time?

My research in The Gambia suggests that human rights, or, more specifically, invocations of rights, are highly contextual— they are invoked in specific situations by specific people who might not consider invoking them in different situations. Rights are also instrumental—they are invoked for a specific purpose that uses the international language of rights which offers hope and a legitimate way to represent suffering and injustice in a way the rest of the world will recognize as beyond the pale. Indeed, this is one of the main purposes of the civic education program—to recast the concerns of young adult- hood as potential human rights issues.

This also suggests that rights are both elastic and something of an a la carte process. In other words, while rights are spelled out in international documents, they are seldom clearly defined. Therefore, people attach new meanings to rights by stretching the language of international human rights law. Furthermore, human rights are also not an all-or-nothing affair—there are many different rights and they do not all play along with each other. For example, the right to the free exercise of religion sometimes seems at odds with the right prohibiting discrimination based on gender. Thus, while human rights may appear as a coherent whole from an international view, “on the ground” people pick and choose the rights they deem relevant to their lives. Accordingly, although the civic education program of The Gambia seems to emphasize human rights issues that appear to be of secondary importance, these issues are the ones that speak in very real ways to the socio-economic realities of The Gambia, as well as to norms of appropriate behavior.

Finally, human rights are aspirational as much as legal. Many times when Gambians talk about rights they are not at all interested in court proceedings, international treaties, or legal opinions. Rather, they use rights as a way to describe their aspirations for social justice, peace, and order. Like the students in the schools I visited, the idea of rights embodies a set of unspecific ideals, hopes, and desires without necessarily implying legal processes and standards.

From an anthropologist’s point of view, this way of looking at rights is attractive, helping us avoid the sterile discussion between cultural relativism and universal human rights that has dogged anthropology since the late 1940s, often forcing us into an uncomfortable compromise. Although anthropologists have upheld the differences among cultures and demonstrated how one culture’s conception of rights and law is completely different from another culture’s, many of us still believe in human rights, even if we disagree over what exactly they entail. We are often alarmed when hearing of (or witnessing) political violence and oppression, and dismayed over the excruciating poverty that many of us encounter while doing fieldwork. In the face of dramatic episodes of violence—such as the Rwandan genocide—many anthropologists think of human rights, not as a cultural imposition, but as a way to secure a peaceful society to prevent further suffering and grief. We also cannot deny the fact that many Africans really want human rights to be better enforced.

Rather than presenting us with a stark choice of acceptance or rejection, my observations in The Gambia suggest that both approaches are in a sense right—as well as wrong! The more nuanced way of approaching rights espoused here still asks us to pay close attention to the local context and consider how particular rights claims resonate or not with cultural norms and local politics. Only by doing so will we understand, for example, why it makes sense for the former majority leader of the Gambian legislature to decry children’s rights while extolling human rights in other contexts.

At the same time, this way of looking at human rights allows anthropologists the opportunity to engage human rights issues from a more productive point of view than merely saying that a given human rights standard resonates (or not) with a cultural norm in their given research setting. By looking closely at human rights as they are transmitted and invoked in particular contexts, we can identify where and how they “stick,” where they encounter resistance, and where there might be alternative idioms that might be better suited to address a given situation.

In The Gambia, a clue to the simultaneous resistance and acceptance of children’s rights can be found in the distinction between the aspirational and the legal quality of human rights. While we may think of these qualities as two sides of the same coin, the discussion of children’s rights in The Gambia suggests that it is plausible to support rights in a loose, hazy sense while being critical of legal actions based on those rights. Indeed, ethnographic studies of law in the U.S. have found a similar distinction between the abstract acceptance of certain rights and the dislike of legal action in pursuance of those rights.

This distinction also serves to underline how thoroughly implicated human rights are with human morality. We—academics, Westerners, human rights activists, whoever—can produce an unending stream of human rights standards, laws, and documents, but, ultimately, human rights touches upon what feels right in a perhaps unacknowledged manner. Just as human rights can offer a convenient way to express a tacit moral feeling, invocations of the legal language of human rights can also uncomfortably jar those feelings and expose the difference between what is right and what ought to be right.

This is, in the end, why thinking back upon my visit to the school for the visually impaired, I still feel uneasy over the discrepancy between the human rights posters and the lack of tenderness—by no means legally required—in the teacher’s aide’s corrections. From an anthropological point of view, the “moral” of the human rights story is far more than “human rights must be moral.” Human rights also encompass a wide range of practices and beliefs that serve to draw connections between peoples and practices, to stake out boundaries between what is proper and what is not, and to provide a way to the relate to the world around, whether a school house, a town, a country, or, indeed, the world.

Cowan, Jane K., Marie-Bénédicte Dembour, and Richard A. Wilson. Culture and Rights: Anthropological Perspectives. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Goodale, Mark. “Toward a Critical Anthropology of Human Rights.” Current Anthropology 47-3(2006):485-511.

Hultin, Niklas. “‘Pure Fabrication’: Information Policy, Media Rights, and the Postcolonial Public.” PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 30-1(2007):1-21.

Hunt, Paul. “Children’s Rights in West Africa: The Case of The Gambia’s Almudos.” Human Rights Quarterly 15-3(1993):499-532.

Preis, Ann-Belinda S. “Human Rights as Cultural Practice: An Anthropological Critique.” Human Rights Quarterly 18-2(1996):286-315.