A few years ago Professor Aaboe of Yale University and Professor Sachs of Brown University dedicated an article to a most distinguished colleague with the sobriquet M.M.E. Needless to say, this rather cryptic titulary did not stem from the queen’s honor list nor did it have any relation to Mechanical Engineering. In this particular case the mythical but richly deserved title of “Master of Museum Excavation” was bestowed on Albrecht Goetze, Professor Emeritus of Yale University.

Courtesy of the Oriental Institute of Chicago

Courtesy of the Oriental Institute of Chicago

The repetition of all of this Assyriological tomfoolery is only to remind the reader that some of the most exciting expeditions in archaeology are to the basements and storerooms of museums rather than exotic areas of the world. The vast collections of the western world were largely assembled toward the end of the last century. At that time artifacts were being excavated and shipped back to Europe and America at such a fantastic rate that it was impossible for museum staffs to catalogue, restore, and properly house their collections. With few exceptions, western museums have still not caught up with the flow of antiquities and their basements and storerooms are full of undiscovered treasures.

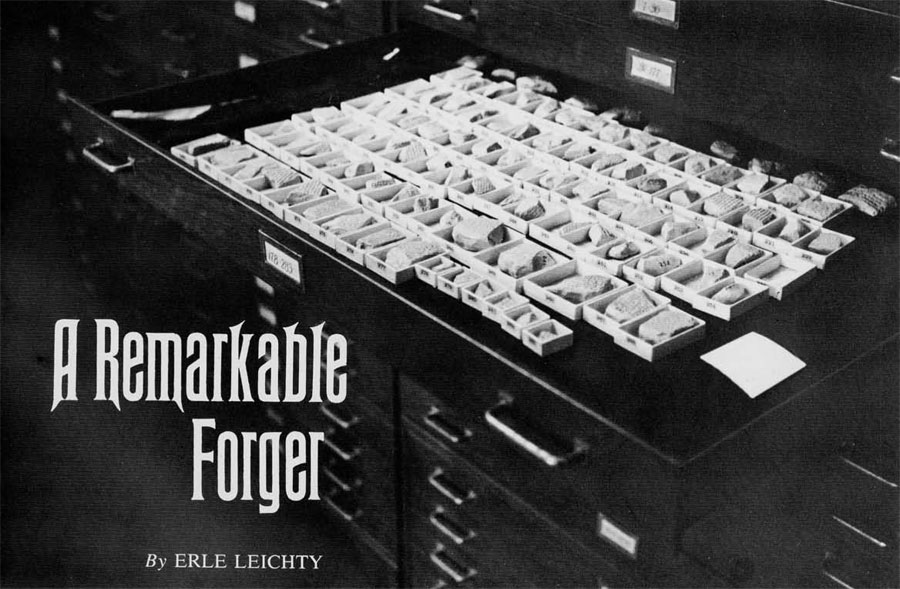

In the field of Assyriology, of course, we rely almost entirely on existing collections of cuneiform tablets rather than on new excavations. We have absorbed such a small percentage of the hundreds of thousands of tablets in museums that new discoveries are almost routine. In a tablet collection the size of the one at the University Museum every drawer holds a surprise. The only problem we have is which drawer to open. And this lengthy digression leads us to the subject at hand.

Last summer, in the course of systematically cataloguing the University Museum collections, I came across a group of one hundred and twenty fragments of tablets which had been purchased as a single lot on July 21, 1888. These tablets, CBS 192-311, had been bought in London by the late Professor Robert Francis Harper from the antiquities dealer Joseph Shemtob. Joseph Shemtob was a Baghdadi and a well known figure in the antiquities trade. Many American collections, including the University Museum’s, found their beginnings in his shop. It is not surprising therefore to note that this lot was only one of several purchased for the University Museum from Joseph Shemtob by Professor Harper.

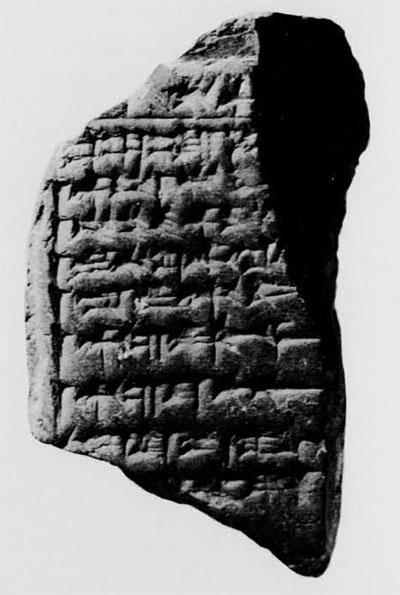

The lot of tablets under consideration consists of small fragments of Neo-Babylonian legal and economic documents. Ordinarily such texts are of very little interest when they are of such fragmentary nature. There are too many complete and well preserved tablets of this type. Besides, all too often, in a fragmentary text either the date, the nature of the transaction, or the names of the crucial parties is broken away. Imagine my surprise therefore, when I discovered that many of the fragments duplicated each other. If that were not enough, it soon became apparent that these fragments were also duplicates of published tablets, the originals of which are in the British Museum.

At this point I began to take a renewed interest in this group of tablets, and certain peculiarities soon emerged. It became apparent that sometimes the obverse of a University Museum text was a duplicate of one British Museum text while the reverse of the same text was the duplicate of a different British Museum text. Thus, for example, the obverse of the tablet CBS 192 is a duplicate of a court case concerning a slave and dating to the reign of Nabonidus (Nbn 13) while the reverse is a duplicate of a contract for the sale of a field dating to the reign of Neriglissar (5R 67,1).

Furthermore, it was obvious that many of the fragments “turned” the wrong way. It was customary for the ancient scribe to write from right to left and from top to bottom. When he reached the end of the obverse, he turned the tablet end over end and completed the reverse. Many of the fragments in the University Museum had been turned from left to right like a modern book rather than end over end as one would expect. In one extraordinary fragment the tablet was turned in such a way that the writing on the obverse and the writing on the reverse are at right angles.

By this time I was quite excited—for a reason that the reader can probably guess. At this point all the evidence seemed to point to the fact that I was dealing with a group of school texts. It only remained to establish the date and provenience of the school itself. I found that a few of the texts were duplicates of a contract for the sale of a field dating to the reign of Nabonidus (Nbn 178) and it began to look as if the school should date from that king’s reign (555-539 B.C.). However, it then turned out that many of the texts were duplicates of a loan tablet dating to 224 B.C. (ZA 3 150). This mixture of Seleucid tablets with Neo-Babylonian tablets was suspicious because the legal terminology had changed between the two periods and we would not expect the later students to be copying outmoded legal documents.

This is where the matter stood about midsummer when I had occasion to make a trip to Chicago and stopped in to see my old friends at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. While chatting with my former mentor, A. Leo Oppenheim, I mentioned my ‘school’ tablets and asked him if he knew of anything similar. As usual Professor Oppenheim had “something in the back of his mind” and he referred me to an article in the American Journal of Semitic Languages.

In that article, published in 1911, Dr. Ivan Lee Holt published copies, transliterations, and translations of a group of Neo-Babylonian legal and economic tablets belonging to the Oriental Institute. These tablets had been purchased in London by Prof. Reginald Campbell-Thompson and had been given, along with other tablets, to the Oriental Institute in 1908. The remarkable thing about them was the fact that a great many were duplicates of each other, but unlike the Philadelphia fragments, the Oriental Institute tablets are complete. As in the case of the Philadelphia fragments, many of the Chicago tablets are duplicates of published tablets, some from the British Museum, others from the Yale Babylonian Collections. Some of the Chicago tablets are even duplicates of the Philadelphia fragments, although Dr. Holt did not know of the existence of the University Museum material.

In assessing the Oriental Institute tablets Dr. Holt wrote: “There seem to be four possibilities of explanation in regard to these duplicates: (1) The tablets are forgeries. A careful examination of the tablets by three very competent Assyriologists and judges of tablets has convinced them that such is not the case. (2) Duplicates are due to the fact that each contracting party took a copy . . . But at least two difficulties confront this supposition in this case —(a) there would be no demand for so many copies and (b) they would not likely, be found in the same place. (3) Duplicates are made to be deposited in the various archives of the administrative and judicial system—as we would send a copy of a document to the county clerk, the secretary of state of the particular state, etc. But the last argument (b) against (2) applies with striking force here. (4) They are practice tablets copied by apprentices in some office or school for the scribes.” Dr. Holt goes on to point out that the same stamp seal is impressed on the edges of many different tablets and that sometimes the obverse and reverse of a tablet are taken from different sources.

Although at this point Dr. Holt and I had reached the same conclusions, we were both soon proved wrong. It was the Chicago tablets that first furnished the truth and I am still embarrassed that it took me so long to realize it. A few of the Chicago tablets are literally coming apart at the seams. As it turns out the tablets had actually been cast; and in two halves—obverse and reverse—and then joined together! Due to the changing climatic conditions in the Oriental Institute tablet room, the tablets have now begun to contract and the seam between the obverse and reverse is readily apparent.

This discovery raised three intriguing questions. When and where were the tablets made and who made them? How were they made? And, how did they manage to fool so many people?

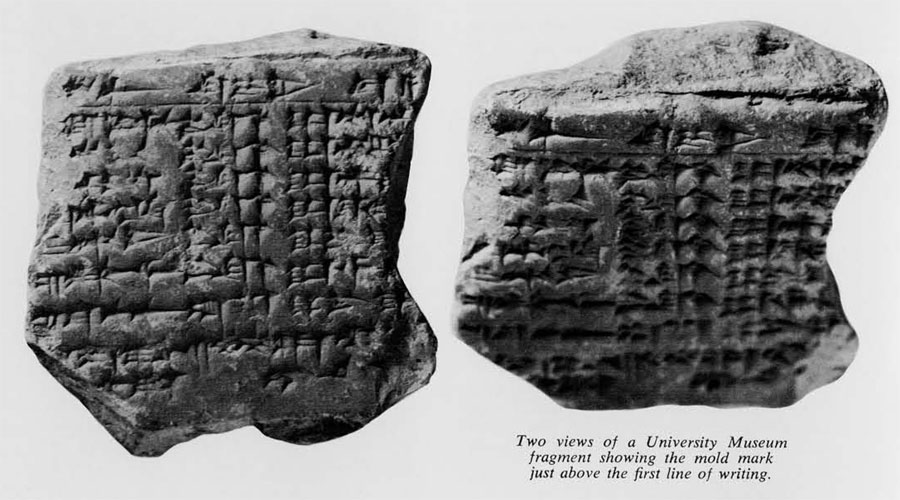

Let us take up the second question first. How were these fakes made? It would appear that the forger made molds of several different genuine tablets. Apparently, with the material at his disposal, it was too difficult to cast the tablet in the round so the forger cast the obverse and reverse of each tablet separately. Then, while the clay was still soft enough he fused the obverse and reverse, trimmed and bevelled the edges, and, in at least some cases, added stamp seals. The addition of the seals not only added authenticity, but also helped to cover the seams. It seems probable that this process was relatively difficult and that the forger practised a good deal before achieving the desired results. The fusion of the two halves probably caused particular difficulty and the forger must have been frustrated by many cases of imperfect fusion. It seems likely that the Philadelphia fragments are the result of this imperfection. When a tablet did not fuse properly, the forger simply cut away the unfused portion and sold the remainder as a fragment. He paid very little attention to these fragments and on some of them the mold marks can still be seen. For his very finest pieces the forger used a thin black slip. Traces of this are to be found on some of the Chicago tablets and on a few of the Philadelphia fragments. This was probably in imitation of one of the real tablets in his possession. Because of the high quality of clay used and because of the fact that the forgeries are actually casts rather than copies, the tablets appear to be absolutely authentic on first inspection.

Who was this masterful forger? We shall probably never be able to point the finger of guilt with absolute certainty, but there are certain clues which arouse our suspicions. The tablets were almost certainly made before 1884. The Neriglissar tablet in the British Museum was published in 1884 and it appears to be the original. The stamp seals on the edges of this tablet belong to the witnesses listed on the tablet. The odds are extremely high against the forger having both the tablet and the original seals at his disposal. It is also unlikely that he would use all of the correct seals. All of the texts were purchased in London, and it seems probable that all were purchased from Joseph Shemtob. The Philadelphia fragments came from his shop. We are not sure whether the Chicago tablets did. With a little more research this problem could be resolved with a reasonable degree of certainty. In the John Frederick Lewis tablet collection of the Free Library of Philadelphia there is a third lot of forgeries and they are accompanied by a clipping from a London antiquities shop catalogue. I have not followed this up, but I feel reasonably certain that the clipping comes from one of Joseph Shemtob’s catalogues. The next question is whether the texts were made in London or Iraq. There is no way of knowing this without an expensive analysis of the clay and even this would probably not be absolutely certain. Anyway, this does not matter if we can prove that Joseph Shemtob knew they were forgeries. If so, then we know that he either made them himself, or at least knowingly purchased them from their creator.

While I can not prove that Joseph Shemtob knew they were forgeries, all the evidence seems to point that way. The originals seem to be in the British Museum. Being in London, Shemtob almost certainly knew Theophilus Pinches at the British Museum and it is highly unlikely that he would attempt to unload forgeries on such a shrewd judge. Instead, we surmise that he sold the British Museum the originals and obtained from them an identification of the content of the tablets which would help him make future sales. Later, when Reginald Campbell-Thompson came around, Shemtob knew him and knew of his connections in the British Museum. He shrewdly sold Campbell-Thompson only the best of his forgeries—the complete tablets in the best condition. Still later, when the twenty year old American, Robert Francis Harper, walked into his shop Shemtob sold him the one hundred and twenty forged fragments along with many authentic tablets. This did not end the sale of forgeries. There were apparently many more forged fragments around waiting for the private collectors like John Frederick Lewis.

Perhaps we are maligning poor old Joseph Shemtob. Surely, with the greedy collectors of the United States and Western Europe scrambling for more and more antiquities toward the turn of the century, many antiquities dealers tried to take advantage of the gullible purchasers. Joseph Shemtob sold many hundreds of authentic antiquities. He also sold some fakes. Was this his secret, or was he fooled too?

The rest of this paper is by way of apology for the naiveté of myself and my colleagues. How did the forger manage to fool so many Assyriologists? The answer to this, strangely enough, is that he didn’t. Despite the fact that the forgeries have been available to Assyriologists for more than seventy years, very few Assyriologists have looked at them, or at least have looked at them carefully. Economic texts from the Neo-Babylonian period exist in the thousands. Individually they are of very little interest, but in large numbers they furnish invaluable information on the economic and social life of the period. Only a handful of Assyriologists have had the inclination to wade through this morass of documentation and of these not all have had access to the forgeries. As a matter of fact, it is doubtful that anyone had looked at them since Dr. Holt in 1911. It is also hard for an Assyriologist to believe that anyone would bother to fake a Neo-Babylonian economic tablet. They are so common that we tend to forget that there is a market for them. And last but not least, we must give credit where credit is due. The forgeries are of excellent quality. The casts are well made and the seams and mold marks are generally well concealed. I suspect that many hundreds of them are in various collections.

If there is a moral in this story I do not know where it is. Certainly the world of forgeries is not confined to cuneiform tablets, nor is it even confined to antiquities. It seems to be part of the human make-up. If there is a market for something there will be fakes. The people in this story were not the first people to be fooled nor will they be the last. Nor have all the fakes been discovered or even made. Let the buyer beware!

Erle Leichty

Erle Leichty obtained his Ph.D. in Assyriology at the University of Chicago in 1960, the subject of his dissertation, Teratological Omens in Ancient Mesopotamia. He was a member of the staff of the Oriental Institute from 1960 to 1963, of the University of Minnesota from 1963 to 1968, and since 1968 has been Curator of Akkadian Language and Literature at this museum and Associate Professor of Assyriology at the University pf Pennsylvania. In addition to articles in scientific publications, Dr. Leichty is the author of A Bibliography of the Kununjik Collection of the British Museum and of the Series Summa Izbu.

Erle Leichty obtained his Ph.D. in Assyriology at the University of Chicago in 1960, the subject of his dissertation, Teratological Omens in Ancient Mesopotamia. He was a member of the staff of the Oriental Institute from 1960 to 1963, of the University of Minnesota from 1963 to 1968, and since 1968 has been Curator of Akkadian Language and Literature at this museum and Associate Professor of Assyriology at the University pf Pennsylvania. In addition to articles in scientific publications, Dr. Leichty is the author of A Bibliography of the Kununjik Collection of the British Museum and of the Series Summa Izbu.