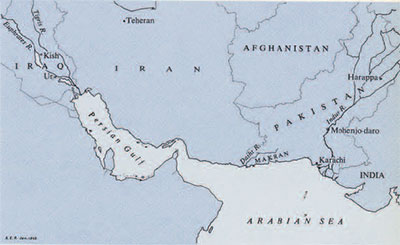

The three oldest civilizations of the old world were centered along the great river valleys of the Near and Middle East–the Nile, the Tigris-Euphrates, and the Indus. Generations of travelers, archaeologists, and scholars have revealed the glories of the Egyptians and Mesopotamians, but the Harappan civilization which flourished in the Indus Valley from about 2500 to 1500 B.C. still presents an enigma. Although far more extensive than either the Egyptian or Mesopotamian civilizations–ranging over one thousand miles from north to south in what is now West Pakistan–it was not until the 1920’s that its existence was discovered and the excavations at the two largest cities, Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, were begun.

Subsequent field work revealed the tremendous geographical extent and the high degree of technical skill and sophistication characteristic of the Harappan civilization. Questions then arose about its origin and possible connections with its highly civilized neighbors to the west, especially in Mesopotamia and the Persian Gulf area.

The extensive excavations at Mohenjo-daro, Harappa, and several smaller Harappan sites have not turned up a single object that can be identified incontestably as coming from the West. Even so, there is good reason to suspect some sort of relationship between these centers of civilization. For instance, there is the question of the origin of the Indus script–as yet undeciphered–that is found on Harappan seals. The “idea of writing” is generally acknowledged to have originated in Mesopotamia. The existence of a script in the Indus Valley thus suggests some cultural connection with Mesopotamia.

Indeed, from Mesopotamia there is concrete evidence of relations with the Harappans. Most convincing are stamp seals with Indus script found in the excavations at Ur, Kish, and other Mesopotamian and Persian Gulf sites.

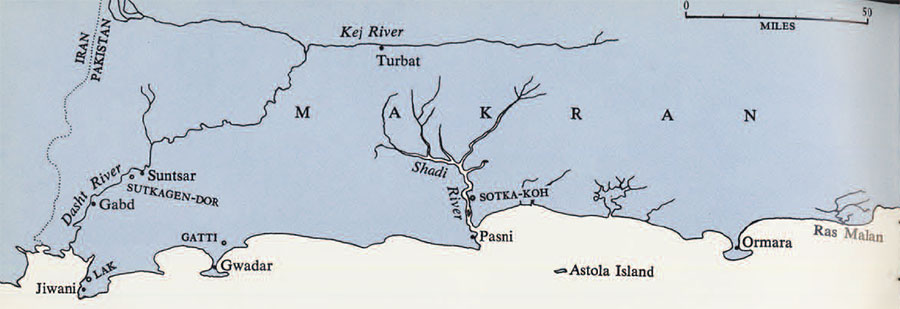

A strong hint of sea contacts between the Indus and the West was afforded some thirty years ago by the identification of a fortified Harappan settlement on the Makran Coast, over four hundred miles west of the Indus Valley itself. This site, Sutkagen-dor, lies in the Dasht River Valley separating southern Pakistan from Iran. Although Sutkagen-dor is some thirty-five miles north of the present coastline, it has been regarded by some scholars as a trading post, somehow connected with the assumed sea trade between the Harappans and the West.

Less conclusive but highly suggestive evidence of contacts comes from the Mesopotamian cuneiform documents of commercial, historical, and mythological nature. They provide many hints of contacts with faraway lands and reflect a well established sea-faring tradition. The identifications of the specific distant lands mentioned in the texts–especially Dilmun, Magan, and Meluhha–are open to various interpretations, but it is certain that the territory controlled by the Indus Valley people would have been listed by the Mesopotamian scribes if contacts with that area did exist. The most recent theory, proposed by Dr. S. N. Kramer, is that the Indus Valley was the Sumerian paradise-land Dilmun.

The literature dealing with the Indus Valley and the West in recent years has become increasingly concerned with this possibility of sea contacts. However, with the exception of two brief surveys by Sir Aurel Stein–around Jiwani and Sutkagen-dor in 1927, and in the Ormara area in 1943–and a limited survey of the Pasni area by Dr. Henry Field in 1955, the Makran Coast has been untouched by archaeologists. Therefore, in the fall of 1960, the University Museum, with the collaboration of the Pakistan Department of Archaeology, conducted a six weeks’ survey of this desolate coastal strip. The purpose was to gather information on the geography of the coast, to search for traces of ancienc habitation, and to re-examine the site of Sutkagen-dor.

On October 1st, T. Cuyler Young Jr., Rafiq Mughal–our representative from the Pakistan Department of Archaeology–my wife, Barbara, and I boarded an old wooden, diesel-powered boat in Karachi and headed westward along the Arabian Sea coast. A rough sea and the incredible slowness of our boat–named the Warrior kept us aboard the ailing craft for two days and two night before reaching our destination of Gwadar.

As is true of all the other “ports” along the Makran Coast, the water in Gwadar Bay is very shallow, so we waded ashore in the customary fashion. This proved to be not only “refreshing” to us personally but provided an endless source of entertainment for the local inhabitants.

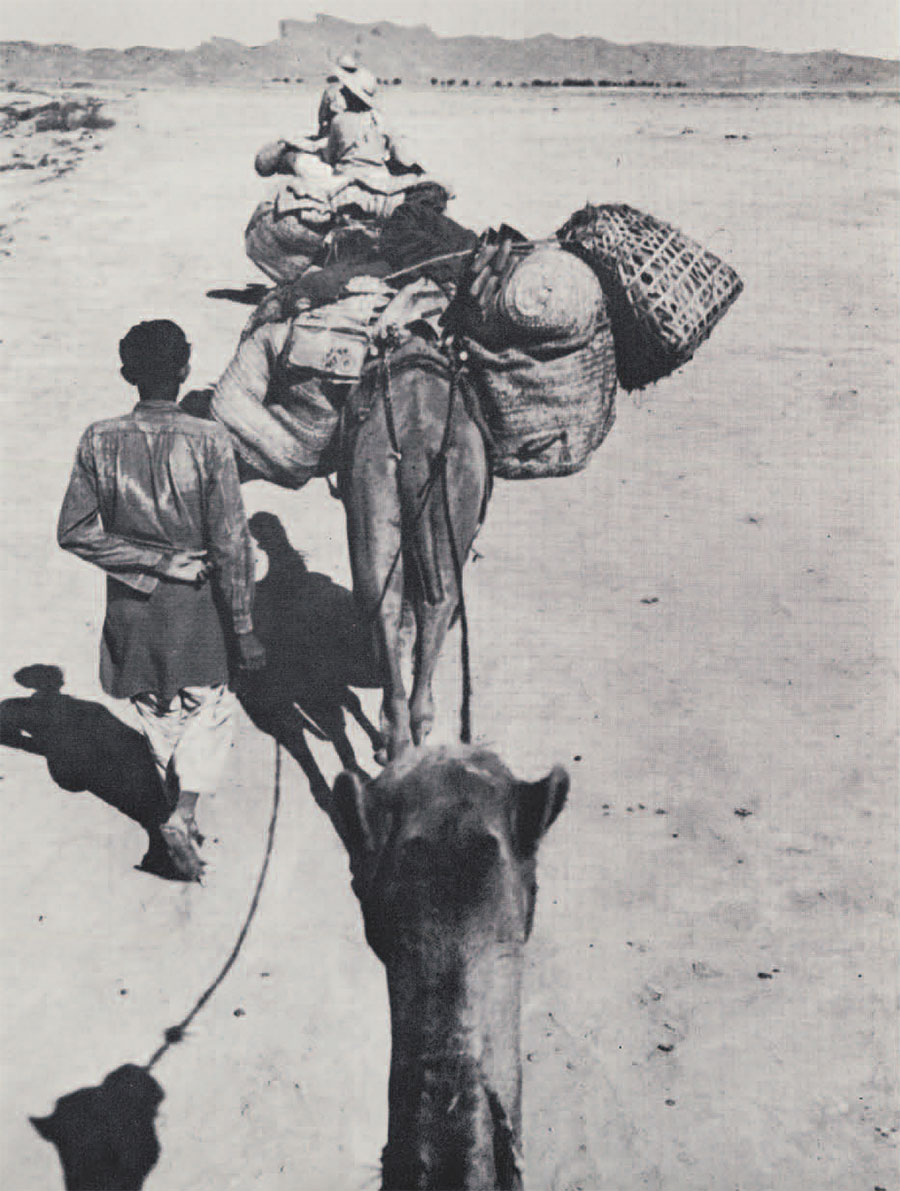

Camels were hired and the next day we started out on our six weeks’ five hundred mile survey which was to cover the Makran Coast from the Pakistan-Iran border eastward to Ras Malan.

Our first objective was to look for archaeological sites between Gwadar and Sutkagen-dor to the northwest. Although this is only a forty-mile trip as the crow flies, it took us eleven hours of riding time to reach the Sunstar Customs Post just east of our destination. The fierce heat that poured down on us as we plodded across the barren coastal plain and wound our way cautiously through the mountain passes was intensified by the appearance of the terrain–at places a virtual Hades of black clinker-like rock suggesting the refuse from some gigantic solar blast furnace.

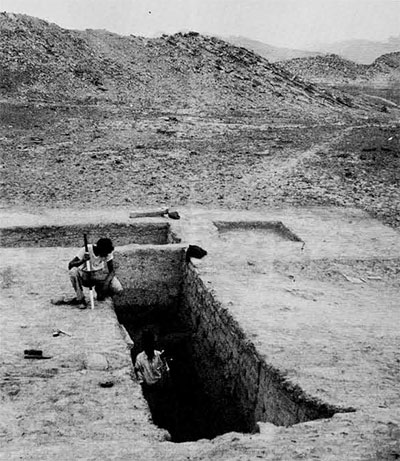

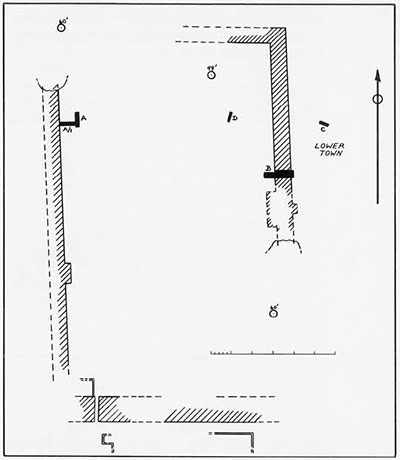

On the morning of October 7th, after a damp, chilly night’s rest on the ground outside the Customs Station, we arrived at Sutkagen-dor and pitched our camp in the midst of the same scrubby acacia grove where Stein had camped over thirty years before. During the next two weeks we surveyed the site and the surrounding area in the light of the published reports of Stein and of Major Mockler, who discovered and partially excavated it in 1876-77; remapped the major structures and natural features; and conducted four small-scale operations to learn more about the fortifications of the citadel and to obtain stratigraphic information concerning the occupational history of the city.

The site, situated on the eastern edge of the vast Dasht River alluvial plain, was built on and around a natural rock outcrop of soft, decayed sandstone which just up at a thirty-five degree angle from the horizontal to a height of about sixty feet above the present level of the plain. It forms a steep, jagged base upon which was built a massive fortification wall of semi-dressed stones. This citadel wall, the sides of which are oriented closely to the magnetic points of the compass, encloses an area nearly large enough to hold four football fields. It varies in height and thickness because of the irregular contours of the natural rock foundation, but at one point about midway along the eastern wall (Operation B) it is approximately twenty-four feet thick at the base. The inner face of the wall is slightly battered whereas the outer face has a decided slope, varying from twenty-three to forty degrees. Our Operation A-A/1, along the inner face of the western citadel wall showed that a large mud-brick platform, approximately seven feet thick, was built there. We observed traces of bastions or towers along the western and eastern walls. Contrary to the observations of Stein, who stated that the inside of the citadel had been washed away, we uncovered stratigraphic evidence of at least three major building phases in Operation A-A/1. The occupational debris at this point is over eight feet thick. Furthermore, stone foundations of regularly laid out structures are visible over most of the surface within the citadel.

The principal entrance to the citadel apparently was in the southwest corner where there are the remains of a sizeable gateway. A narrow passage-way about five and a half feet wide, passes for almost forty feet between what must have been massive towers guarding the entrance. Outside the southern citadel walls, but still on top of the rocky outcrop, are the foundations of other regularly laid out structures.

The “lower town” outside the citadel complex seems to have been concentrated along the eastern side of the site. A trench, Operation C, excavated to a depth of fifteen feet below the foundation of a structure visible on the surface, produced only sterile alluvial deposit. However, the pottery shreds collected from the citadel and the lower town provide a suggestion concerning the inhabitants of the site. The pottery from the stratigraphic trench A-A/1, inside the citadel wall and from the clearing of one of Stein’s trenches, Operation D, probed to be of pure Harappan stock. Less than a handful of shreds from the surface of the Citadel are of Baluchistan rather than Harappan manufacture. The pottery from the lower town, however, appears to be more closely related to the various Baluchistan traditions which are at least partly contemporaneous with the Harappan period.

From our observations at the site itself, we were indeed skeptical about the possibility of Sutkagen-dor ever having been a seaport, but after travelling down the Dasht Valley to the sea, surveying the rest of the Makran Coast, and then checking our guesses against the results of the latest geological surveys, we came to quite the opposite conclusion. The incredible amount of alluvial buildup in the valley gives us now a misleading impression of the geographical situation four thousand years ago. Sutkagen-dor could well have been an actual port, or at least control point at or near the mouth of the Dasht River. In fact, certain features suggest that it may have been an island during Harappan times.

Early in the morning of October 20th we loaded our supplies and ourselves aboard seven camels and started the slow trek down the Dasht Valley to the Arabian Sea Coast. By noon we had reached Kalatu, where, after securing drinking water and resting for an hour in the shade of a rather thickly treed area, we visited the remains of the fort that gives the place its name. All that remains is a square mud-brick defensive-type tower perched precariously atop a severely eroded sandstone outcrop. How much larger the original fortification was it is impossible to say, but this tower at least seems to have been an isolated structure. Situated in the center of the vast plain, it afforded a lookout against any movement in the area. The date of the fort is unknown but the accounts of travelers mention the ruins over eighty years ago. At the base of the steep outcrop are the remains of a settlement of recent date. Until about twenty-five years ago this had been the location of the village of Kalatu, but the entire village moved to its present location nearer the river because of an epidemic. This local disaster provided us with an interesting opportunity to observe what is left behind when a settlement has had to be abandoned. The study of such recently abandoned settlements can be helpful in our efforts to interpret the remains of similar ancient settlements. For example, we obtained an interesting bit of information–confirmed at other Makran settlements–from the thousands of potsherds lying on the surface. Most of them are of micaceous clay painted with black-on-red design, identifying them immediately with the modern pottery of Sind, the lower Indus Valley area around Karachi. Pottery is not manufactured today at any point along the Makran Coast. Some is brought down from the Kej Valley but the greater part is imported all the way from Karachi. Indeed, as we recalled our boat trip from Karachi to Gwadar we remembered noticing that practically all the passengers had at least one of the colorful, but fragile pottery vessels with them. The old notion that pottery cannot be transported over long distance does not hold along this coastal area today. The same situation probably prevailed in Harappan times, with pottery being exported to the western outposts along the coast by boat.

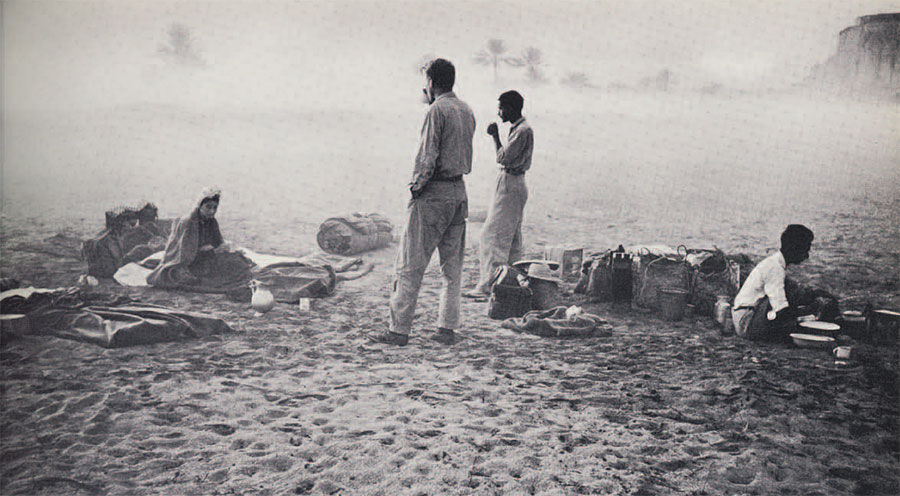

A two and one-half hour ride later in the afternoon, through a mild dust storm, brought us to Gabd, also on the east bank of the Dasht–a fairly sizeable reed-hut village stocked with quantities of cattle, sheep, chickens, and children. After a bath in the lukewarm water of the river, and a tasty curry dinner, we settled down for a welcome night’s sleep in a grove of trees just outside the village. The next morning we visited the site of old Gabd, about a quarter mile to the east of the present location. It was abandoned some twenty-five years ago because of bad water. Just as we had observed at old Kalatu, no discernible tell of occupational debris had been built up. Both sites were marked only by the bits of broken pottery, glass, stone, and metal that lay on the surface of the ground. It demonstrated that it literally takes a pile of living to make a tell.

At five o’clock that afternoon, after a tiring march across the barren, featureless plain, we arrived at a dried-up hole named Chatani Bal, about twelve miles south of Gabd. Hoping to reach Jiwani by nightfall, we continued on to the south, but halted after another half hour. We were at the northern edge of the “swamp,” a huge area just north of the Jiwani Promontory which doesn’t even support camel forage. Although within sight of the search light at the Jiwani airport we were still hours away from our destination by camel, and our drivers refused to continue through this area after dark. We unloaded our supplies near a lonesome scrubby tree and camped out under the stars.

Soaked and chilled by the early morning fog that rolled over us from the sea, we were packed and on our way before sunrise. Upon arriving at the Burmah-Shell Rest House just north of Lak Plateau in the northwest corner of the Jiwani Promontory we were invited to stay there as guests. This served as our base of operation for our five-day survey of the promontory. Much of our attention was directed toward the numerous stone circles, supposedly burial cairns, on Lak Plateau, many of which had been opened by Stein in 1927. From his dump piles we collected a representative sample of pottery, including some fine examples of bichrome painted pottery with pothook motifs. There is no positive identification for the builders of the circles nor is their assumed burial function altogether clear. Similar circles are still built and used for religious ceremonies by the Zikris and the Brahuis. Many of them are also Moslem prayer-circles, some built recently but others clearly remodeled ancient circles. We made a thorough survey of the rest of the rugged promontory, by camel and on foot, but found no other pre-Islamic remains.

To see as much of the actual coastline as possible we went from Jiwani to Gwadar by boat. On October 27th we boarded a small fishing sailboat, about twenty-five feet long, for a slow but delightful ten-hour sail along the coast. After wading ashore in West Gwadar Bay, we camped out on the beach for the night. The next morning we moved into the old and partly demolished Rest House and began our six-day visit. A foot survey was made of the entire rocky promontory–Gwadar Head–that serves as a protective screen against the fury of the sea and wind for the present town of Gwadar. Several groups of stone circles, similar to the ones at Jiwani, were located but not a single potsherd was found near them. Remains of long stone walls were found at several points. These so-called gabar-bands were certainly not built as dams for the storage of water. A recent study of the numerous remains of such structures indicates that they were check-dams, used to retard the flow of rain water long enough for it to deposit its rich cargo of silt, thus creating an artificial terrace of precious cultivable land. The dating of such structures is uncertain. However, sherds found near several such walls indicate that they were built and used over a considerable period of time–possibly for over two thousand years. In one place the only sherds found were Islamic, whereas at another place there were painted sherds of the Nal tradition, roughly contemporaneous with the Harappan civilization.

Mockler and Stein reported a group of stone circles at Gatti, near the northwest base of Jebel Mehdi, on the mainland just north of Gwadar. We devoted a full day to an investigation of this weird moonscape area. Only after many hours were the cairns located. The few pieces of pottery found there were of coarser ware than the Jiwani sherds and were not painted.

The passage from Gwadar to Pasni, the next port to the east, was made by small motor launch. Our stay at Pasni was cut short by the exigencies of securing transportation to our next base, Ormara. Transportation facilities are so scarce and so sporadic along the coast that you may wait anywhere from a few hours to a few weeks for the next opportunity to leave a given port. Three days of intensive surveying and questioning of the local inhabitants of Pasni produced the major discovery of the entire survey. Mir Ahmad Khan Kalmati, head of the once powerful Kalmati tribe at Pasni, was our chief informant on the antiquities of the area. He told us of a large ancient site on his property, north of Pasni, covered with burned pottery and ashes. From his description of the pottery he had picked up on the surface, we knew immediately that we were on the trail of another Harappan settlement. With the aid of a Jeep lent to us by the Department of Fisheries we made a hurried trip to see the place for ourselves. This site, called Sotka-koh (“Burned Hill”) is about nine miles north of Pasni in the Shadi Kaur Valley. It is almost identical to Sutkagen-dor in size, appearance, and geographical location, built on top of a jagged natural rock outcrop, situated in an alluvial plain along the eastern side of a wide river valley. A stone wall can be traced for over sixteen hundred feet along its eastern edge. The rest of the site is so badly eroded and denuded that it was impossible to determine much about its layout. However, on the higher parts stone building foundations are visible. The pottery is identical to that found on the citadel at Sutkagen-dor. About two miles south of Sotka-koh, the valley funnels down through a relatively narrow pass through an east-west range of hills. The site could thus never have been directly on the sea-coast, but if that range of hills represents the coastal range of antiquity, Sotka-koh would have been in the ideal strategic position to control traffic between the coast and the interior.

Three natural forces have worked together to radically alter the geography of both Sutkagen-dor and Sotka-koh: the still continuing uplift of the coast, the rapid alluvial buildup at the mouths of the Dasht and the Shadi Kaur Rivers, and the steady building of beaches through the deposition of sand by wave action. The combined result of these phenomena is most readily apparent in the Dasht Valley, but is also observable south of the entrance to the valley in which lies Sotka-koh. For example, it would take only a relatively slight depression of the coastal strip and the disappearance of three to four thousand years of alluvial deposit to allow the Arabian Sea to reach the thirty-five miles north that Sutkagen-dor now lies from the coast. The same is true of the range of hills south of the Sotka-koh Valley. With the coast only a couple miles south of the site in antiquity the tidal waters would have been high enough to permit boats to reach inland at least as far as the Harappan outpost. Thus we now have two Harappan settlements on or very near the ancient Arabian Sea Coast, over four hundred miles west of the Indus Valley itself. Each one is situated strategically at the entrance to a major route from the sea to the interior. With these two outposts the Harappans were thus able to control much of the economic life of southern Baluchistan as well as to have way-stations for coastal sea trade with the West.

From Pasni to Ormara, our last base of operation, we again traveled by motor launch. Geographically Ormara presents exactly the same situation as does Gwadar–a high rock promontory connected to the mainland by a thin sandy spit, on which is located the present fishing settlement. An arduous climb got us to the top of the Ormara Head where we conducted a survey of all but the extreme western end, which had been visited by Stein in 1943. This Head proved to be much more barren than that at Gwadar. A few stone circles along the southern edge were the only signs of ancient occupation. Intensive questioning of the local authorities and village elders failed to turn up clues to any pre-Islamic ruins along the coast either side of Ormara.

The final, and by far the most strenuous, stage of the survey took us some thirty miles east of Ormara to the rugged and rocky promontory called Ras Malan. An isolated account in the old Baluchistan Gazeteer describes the remains of an ancient settlement and cemetery on top of the cliffs. An agonizing twenty-four hours in a cramped fishing boat finally saw us on the beach at the mouth of the Sorab Kaur Valley. Our aged guide, who is one of the few permanent residents of the inhospitable promontory, led us up the Batt Kaur Valley where after an hour and three quarters’ march we reached a cemetery. Most of the graves were of recent Islamic origin but there was a series of carved sandstone “Rumi”-type tombs of uncertain date and attribution. A thousand foot climb up an almost vertical path put us on top of Batt Plateau. At this point our guide failed us completely, confessing matter-of-factly that he did not know where the ruins were. The top of the Ras is an immense tableland cut into irregular sections by thousand-foot-deep gorges and would require a week of difficult, waterless surveying to cover. We did explore a considerable portion of the southern half of the promontory without finding the ruins we were after. Many Zikri ceremonial circles were seen but nothing suggesting occupation of either a permanent or temporary nature.

A comfortable twenty-hour ride atop the wheel-house of a country-craft type boat and we were back in Karachi on November 16th, fully satisfied with the results of our survey. Concrete evidence had been found to support the theory of Harappan sea trade with the West. The recent discoveries by Indian archaeologists of actual Harappan shipping docks at Lothal, north of Bombay, add further evidence that the Harappans were engaged in Arabian Sea trade. Just what percentage of this trade was conducted with Mesopotamia and the Persian Gulf area is unknown. Southern Iran, Arabia, and possibly East Africa may have participated in at least part of the trading activities. The task for archaeologists now is vertical investigation in the Makran area. A highly desirable project would be the full-scale excavation of a site in the Kej Valley, near the head of either of the two major routes from the sea guarded by Sutkagen-dor and Sotka-koh. This could provide sound archaeological evidence of trade and contact with the West by both the sea and the natural and route along the Kej Valley, as well as information on relations between the Harappans and their Baluchistan neighbors.