Fields are cleared by slash and burn methods.

Much of the initial information gathered on foreign peoples has been derived from the accounts of travelers. Such accounts are usually of an informal nature involving personal experiences seldom included in technical anthropological studies. Yet the very intimacy of such personal contacts, combined with the traveler’s observations on foreign customs, documents in a manner similar to that found in well written modern novels (all too often overlooked as excellent anthropological material) the very human aspects of these cultures.

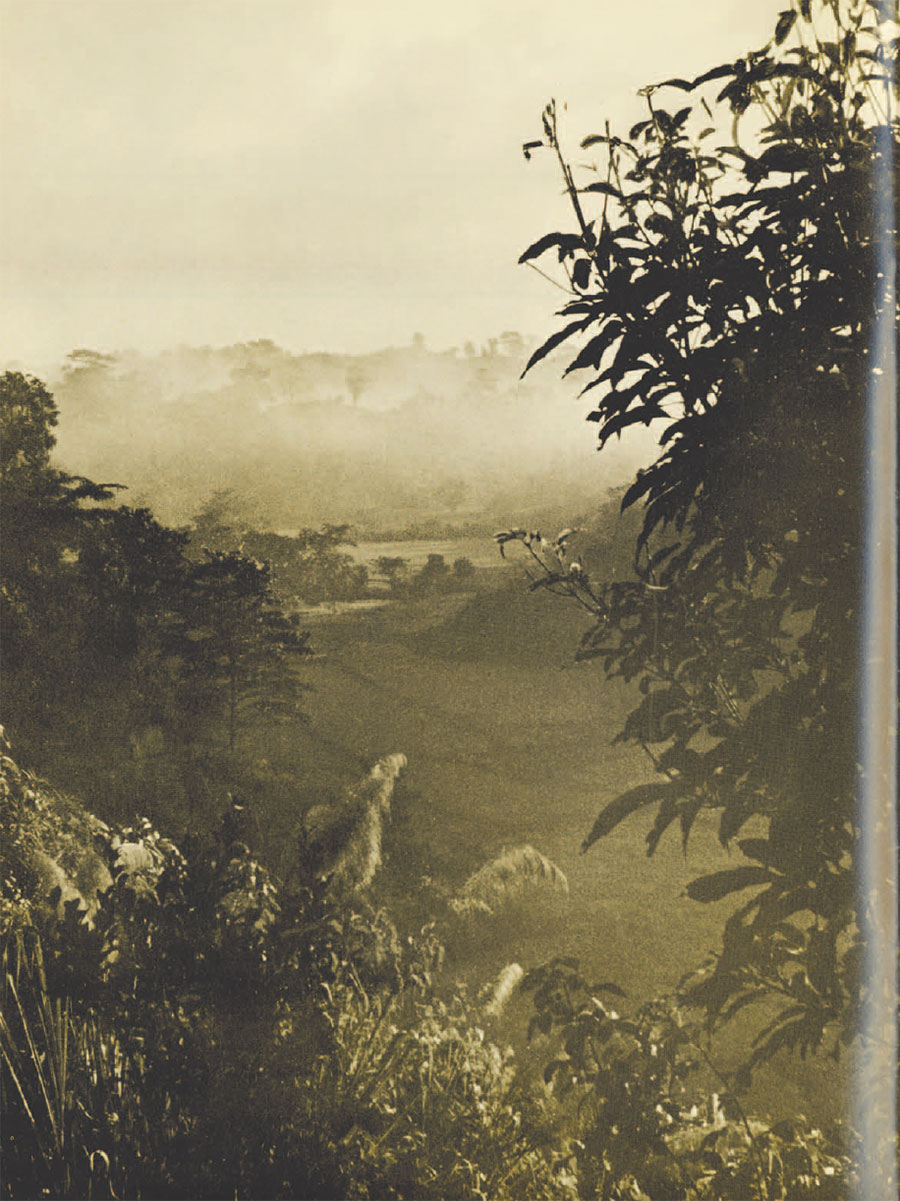

The following few pages are extracted from an account written during a visit to Banderaban in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of East Pakistan in the winter of 1957. I visited several tribes on this trip of which only one, the Magh, is here described. The group is of Thai origin and settled in the region toward the end of the eighteenth century. It subsists principally on slash and burn agriculture carried on in heavy forests produced by the more than one hundred inch rainfall the area receives each year. The hills are nowhere higher than about four thousand feet above sea level and are filled with a number of primitive and immigrant tribes who practice animistic Buddhism. One of the two most powerful Magh clan chiefs, the Bohmong, is a lineal descendant of the Mon kings of Pegu (Burma). The tribe is of interest from the point of view of its adaption to living in this particular environment where the major raw material is bamboo and wood. It is also of interest in that it represents the western frontier of Tibeto-Chinese speaking peoples with a southeast Asian culture facing the Bengal plain with its increment of Near Eastern influences. While many of the Maghs have come under Bengali influence, those in the hills have retained their Burmese script and dress and continue to speak a dialect of Arakanese.

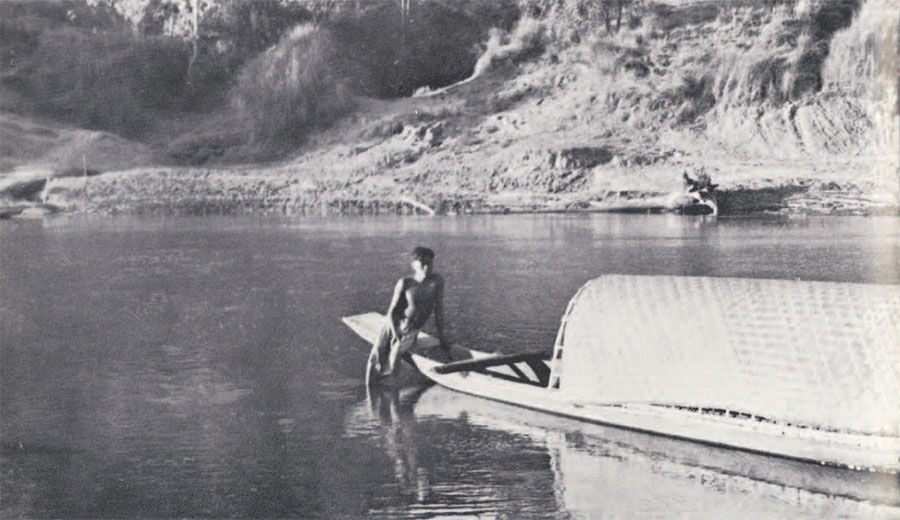

Monday, December 9th. The countryside is covered with brown golden rice being harvested–a great contrast to a month or so ago when it was all vivid green just after the monsoon. The train conductor came along and said I’d have to pay double for Mumtaz, my seventeen-year-old translator, because he had no ticket! I protested vigorously that the ticket seller had assured me I had all the tickets I needed. He insisted. I paid. Ah, the East. He then explained to Mumtaz about getting a boat to Banderaban, the administrative capital of the Magh tribe. As he left he asked me not to be angry with him because after all “the government made the rules.” At Dohazari we got down from the train and went along to the river bank. There we hired a dugout for eight rupees to take us to Banderban. An old riverman and a young boy ran the boat. A short distance upriver we stopped at the Dohazari bazaar to buy food and drink, two cups of hot tea and milk. Bought six oranges, a papaya, and bananas, which we had for supper. The young boy cooked fish and rice on a tin tanaker stove just behind the cabin (a curved bamboo and mat roof set over the fore-section of the boat) for the old man who was poling us along the shallow river. Boats glided past, their poles making grating sounds in the sand as they sank in. A pale evening haze settled over the shores. Then it was night and fires glittered near clusters of bamboo houses and people walked along the high banks carrying bamboo flares to light their way, calling to one another. Lights from the boats streamed over the water and the Bengali boatmen talked and laughed to one another as they passed. Mumtaz and I unrolled our sleeping bags on the hard floor in the cabin and crowded in to sleep. Outside the moon came out.

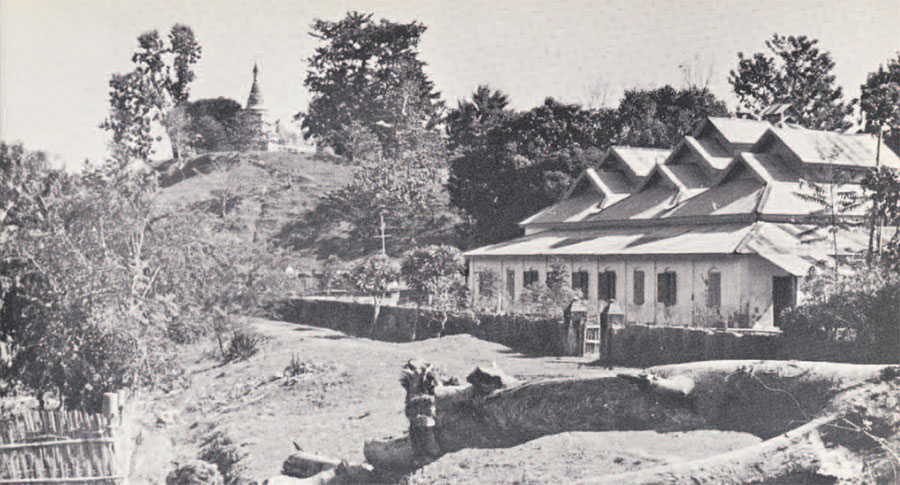

Tuesday. We awoke with stiff muscles and many mosquito bites. A cold morning fog transformed the river and hills into a kind of Japanese print. At seven, while we ate our oranges and bananas, the sun broke through. At a bend in the river among high hills we landed at the small beach which services Banderaban. We climbed the steep slope to the bazaar and stopped in a wooden shop for tea and bread. A local boy took a note to the administrative offices asking for use of the Dak bungalow–the official guest house reserved for visitors. Meanwhile we met a police officer who suggested we walk over to the office. We did and I handed in my paper identification slip, but as usual was also asked for my passport, which necessitated a return trip. The Dak bungalow crowned a high conical hill which lay across a small bridge near a Buddhist temple or khyong. The view was splendid but there was no water and no watchman!

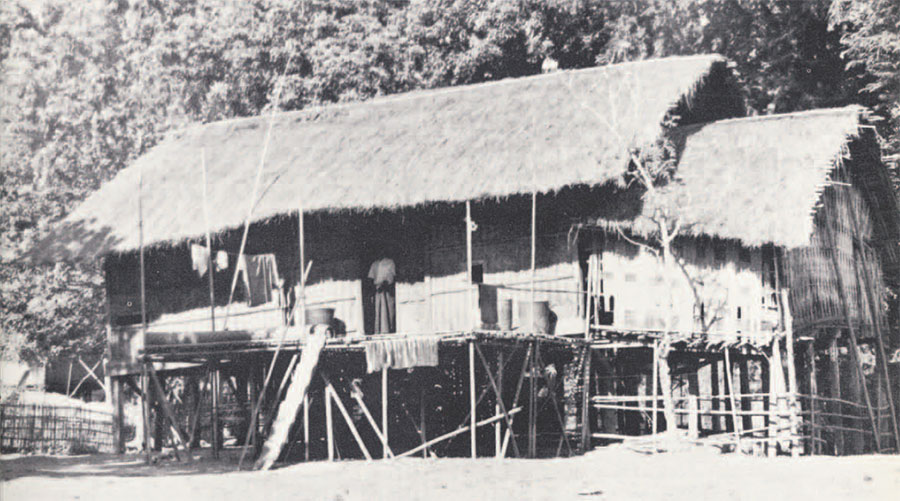

The officer in charge of the police office was from the Chakma tribe. From him we obtained a guide to the office and palace of the Bohmong, built in 1934. This proved to be a great three story house with white walls, green shutters, corrugated tin roof, and bars–even on the second floor windows. The ordinary houses at this end of town are all on bamboo stilts with notched log ladders up to the front–not to the side as among the Chakma tribe. The front porch is smaller than the house and often roofed over, or at least has a high mat fence. Brass pots are often visible. The houses are set in square or rectangular plots on either side of the road. The main road itself is of red brick, the most durable available material. Administrative offices are downriver, the bazaar is in the center, and the residential area is upstream.

The khyong, or temple, lies back from the river beyond the bazaar. A jutting hill behind the khyong supports a Buddhist shrine. Saffron robed priests occasionally may be seen gliding up or down the hillside steps. Nearby in the village is a large tank or earthen reservoir for drinking and bathing water. You do not find these among the more northerly Chakma. The bazaar is run mostly by Bengali merchants from around Chittagong down on the plain. They sell pottery, cloth, and hardware imported from the plain and run innumerable tea shops. From these stores the essential equipment for daily living is obtained–especially metal tool blades and pottery containers. Townsmen are often dressed in cloth bought at these stores–white turbans, lungis (cylindrical one-piece skirts) and white jackets. Women wear colored skirts (and sometimes blouses), silver armlets and anklets.

Thaddaw Chawtunpru, the second son of the Bohmong, joined us. He brought us his father’s greetings and a request to be excused from receiving us. The Prince explained that the Bohmong was suffering from “swollen feet” and only a few days before had had to leave the Durbar after only a couple of hours because of them. We were invited, however, to come and call upon our return to town after our walk in the hills.

Sitting on the hilltop on the porch of the Dak bungalow at sundown one hears the noise of insects filling the tall trees and grass–otherwise quiet in the day–mingled with the sounds of chickens, cocks crowing, cows lowing, and children shrieking at play. The village is marked by a low hanging cloud of smoky blue drifting to the hills. Originally Banderaban was the chief center of habitation, with people going out five or six miles to jum (that is, to clear their field by slash and burn methods). Around 1918 the group split up and settled in new units. At present there are some two hundred houses with about two thousand people here.

Just as Mumtaz was heating my pail of bathwater, Thaddaw Shwe, another member of the royal family, came along with a letter from the Bohmong and a twenty-year-old Magh boy named Kyatung Aung. He is to go along to translate Arakanese into Bengali so that Mumtaz may translate Bengali into English for me! I walked down to the village with Thaddaw Shwe asking questions. Each house has a plot of ground but there is no charge for it. Taxes are on the area jumed. The local area exports cotton, sesame, and rice along with bamboo and wood in exchange for cash. The Maghs never go outside the hill tracts to work. Instead, Bengalis come in to work as merchants and boatmen. Many of the Bengalis have been born here. The Maghs say that the Bengalis are very clever and always do the hillsman our of his cash! It is also reported that the Bengalis sometimes obtain land when the administrator is Bengali–but never when he is a Christian or a Hindu. Merchants in any case must have a permit to operate in the market. This as a rule is given in favor of the Bengalis.

There are a couple of “Hotels” in town, and a new “Club” open to all for one rupee a month. As everywhere else on the subcontinent, the opening of the “Club” to the local citizens symbolizes the end of colonial status. There is also a liquor store where country wine may be purchased at one rupee for “standard quality,” two rupees for “better quality,” and four rupees for “distilled.” Of course the real quality of these “qualities” varies, and hillsmen have guilty feelings going in to buy what is traditionally give freely as a form of hospitality in the hills. Needless to say, the Muslim Bengalis disapprove of it altogether for religious reasons. We bought some wine, some mustard oil, some chicken and duck eggs, and some bananas.

Along the road were variously placed open-sided platforms with roofs. These are provided with water jugs kept freshly filled every day by the villagers as a courtesy to the visitors who are allowed to rest there. In one house an old man squatting on a bamboo floor and smoking a long pipe, was silhouetted against a woven mat wall lighted by the fire’s reflection. When we asked what he was doing he replied, “Trying to keep warm.” Nearby some Bengali youngsters were playing marbles. They stood behind a line and rolled the marbles toward a hole. If the marbles touched, the roller won. In the distance the gongs of the temple erupted against a background cacophony of clanging noise. The night cold and fog were settling in and I hurried back tot he bungalow and supper.

Wednesday. Up at seven in a gray and damp world. I was awakened by Mumtaz who came into the bath to wash before saying his prayers. We went into town to the tea shop and had two glasses of tea, two fried eggs, and four round bread cakes. At 9 A.M. Kyatung appeared after Mumtaz went for him and found him sleeping. Advanced him twenty rupees. He hired a porter with a big basket on a trumpline to carry our gear–for two rupees a day.

Setting off, we followed the old World War II jeep road cut through the jumed forest up and down steep hills. Shwe had told me that Lord Mountbatten had been in this area during the war when the Japanese were thirty miles away. Mountbatten had a detailed map and wanted the Maghs to form a guerrilla battalion to fight the Japanese with British supplies. But the plan called for no uniforms or open recognition–only an underground unit. The Bohmong said, “No, give us open recognition and a name so we can be proud of it and we will fight.” But no name was given and they never did.

The road led on through cool breezes and hot open areas full of dead stumps, occasionally along high cliffs–much green–many fallen brown leaves–rather like fall in New England but with the hills closer together and no blazing colors. We walked an hour and rested five minutes at a crossroads.

Foot roads like the one we were now following are the only transportation routes other than the rivers in this area. A Magh man in a green lungi and a woman in a clean white turban and red lungi came along and sat down for a smoke. Maghs sometimes adopt the plainsman’s method of carrying a burden suspended at each end of a shoulder stick but more often use the traditional trumpline. There were lots of plainsmen on the roadway including a few who had apparently found the Magh trumpline more comfortable. Two of these sat down with us and with some hesitation began to smoke cigarettes. They explained via Kyatung and Mumtaz that they were afraid I would not approve! No doubt I was taken for a missionary…After walking a second hour we stopped at a roadside tea house for a cup of hot tea. Then another hour at the end of which we descended to a small river and after crossing several log bridges arrived at a village (Magh villages are always built next to a stream) to whose headman the Bohmong had given us the letter. We were ushered at once into a house for a rest while our host-to-be was informed of our arrival.

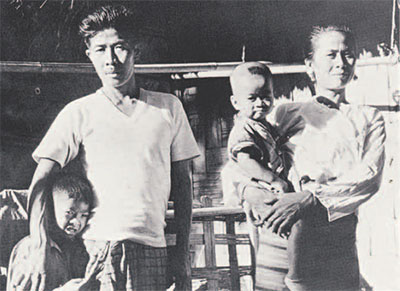

As I relaxed in the guest corner, the area to the right of the front door, which is reserved for visitors, my attention was engaged by a cradle hanging from a rafter. A child was sleeping on its back, carefully protected from illness by charms in the form of bamboo chains which had been placed by a Buddhist priest, one on each of the supporting ropes, about three feet above the basket. The mother had on a white turban, silver earrings, bracelets, anklets, and a fine necklace of coins. The nose ornament, common on the plains, is not found here. The handwoven hair strip is usually about three inches wide and two feet long and elaborately patterned. The man of the house wore a Western-style imported T-shirt and traditional lungi. His hair was cut quite short and parted and combed to the side.

After a short wait we were shown into a second house, that of the local headman’s “village manager.” His house was a typical one functioning on three levels. On the ground among the stilts on which the house rested, was a fenced area in which the household animals–pigs, dogs, cows, and chickens–were corraled. An open space was left between the top of the enclosing fence and the floor level of the house for the flow of fresh air. The second or floor level stood about ten feet off the ground. Above this, under the roof was a third, rafter, level used for storing baskets and equipment. A closed kitchen shed opened to the right while an open porch lay before the entrance. The basic structure was rectangular with four posts set along the front and back walls and a single post on either side. The roof consequently sloped to the front and back. About a quarter of the interior space in the rear left corner of the room was partitioned off as a storage area. The main part of the room was about twelve by eighteen feet with the guest area to the left of the front door. The door was equipped with wooden panels and just behind it was an openwork grate set into the floor. This provided a work area, as debris could be dropped through to the ground below where the pigs disposed of anything edible. To the right was the family sitting area in the center of which was a movable bamboo hearth filled with sand, upon which fires were lighted. Around this at night the family gathers to tell stories and talk over the day’s activities. Normally this is the time of year when people are in the village. It is a time of resting and social gathering as opposed to other times when they are busy out in the jums. But nowadays this is also the time when labor is needed away from home to run the wood and bamboo trade in the money economy. Hence a strain is placed upon the normal cycle of village and home life.

The objects in the house reflect the simple needs of the householders and also illustrate the substitution of more permanent materials for older objects, especially containers and cutting implements. Acceptance by a culture of the more durable and practical objects which may be used without disturbing the traditional values involved in the activity seems to be a common process. In the corner of the room were more baskets, two pottery pots, a gasoline tin, a pole with clothing hanging on it, and a broom. Elsewhere there hung a small mirror, an iron sickle blade, two iron hill knives, four drinking glasses, two black umbrellas (the hallmark of a gentleman in Chittagong), and a bamboo cradle. I also noticed two glass bottles, an extra pottery pipe bowl, two cloth bags, and wooden parts of a spare plough. Among the rafters, along with a playful pet kitten, were bamboo offering containers for the pujas set out in fields or along streams to placate the spirits and bring good luck. These usually consist of a structure of bamboo as protection and some kind of bamboo or basket container stuck in the ground and filled with flowers. These offerings to spirits form part of the ritual practised by these hill Buddhists, and represent a carry-over from pre-Buddhist animism.

Since hospitality is one of the first requirements of a good Buddhist, the guest is immediately made comfortable in the area reserved for him. In this case the dignified mistress of the house spread a finely woven mat on the floor and covered it with a white homespun sheet with a second folded as a pillow. Sheets are woven by the women from homegrown cotton and measure about four by six feet. These two were decorated with stripes of red and black. Kyatung went to the kitchen to prepare lunch. Meanwhile curious neighbors dropped in and out to see the stranger. They all were most courteous and had big smiles. The wife sat by the door where the light was best for picking cotton clean. Her hair was tied in a bun at the back and she wore tubular silver earplugs decorated on the flat ends. A little girl sitting near her had the front hair on her head shaven while the back hung in long tresses. Her little sister wore silver anklets and two brass prayer lockets around her neck. I offered the adults cigarettes. The little boy of the family suddenly began bawling loudly; so I had to give him one too. He wore a brass ring in the right ear and a strip of hide in the left.

After sitting in the house writing for an hour and a half I was approached by the wife who presented me with a bottle of rice wine. This indicated that she had finally approved of me and was offering me full hospitality. I never did find out what “quality” it was but it had a kick like a mule and burned all the way down! Kyatung brought lunch: red rice, chicken curry, aram and curry, the wine, tea, pan leaf to chew, and an orange. Later we walked over to the headman’s village just down the valley but he was away. A detached cow’s head was lying in the path looking very lonely indeed. Our hose said that eight cows had been killed the night before by tigers. We were glad to climb the log back into the house!

At night little tin lamps imported from the plains are used for light. The family gather around the glowing hearth and the room is filled with dancing shadows, geometricized by the linear patterns of the bamboo mat walls. The room is a study of yellow and browns. The mother with her two-year-old daughter, the father and his six-year-old son, and an older man warm themselves by the fire as it has grown cold outside. The two children were clearly vying for attention and demanding their own way constantly. Not only demanding but getting it. The parents are very permissive. The boy saw our oranges and began screaming for one, followed immediately by the baby. We gave one to the boy who was very pleased but kept it for himself. The child kept yelling until the mother quieted it by giving it the breast. Such permissiveness in childhood is no doubt connected to the apparent lack of self-discipline seen in so many adults who clearly prefer to do only what pleases them. The family watched me eat my dinner which was served on a low round table along with the bottle of wine. When I had finished they all went into the kitchen and ate their rice dinner with their fingers out of big pots. After dinner they returned and sat talking and smoking their long pipes with metal mouthpieces and pottery bowls. The children fell asleep and were placed on the floor together under a couple of homespun sheets. I crawled into my sleeping bag. Mumtaz made his bed on one side and Kyatung on the other. Outside the boys built a fire down on the ground and sat talking and singing little songs to one another.

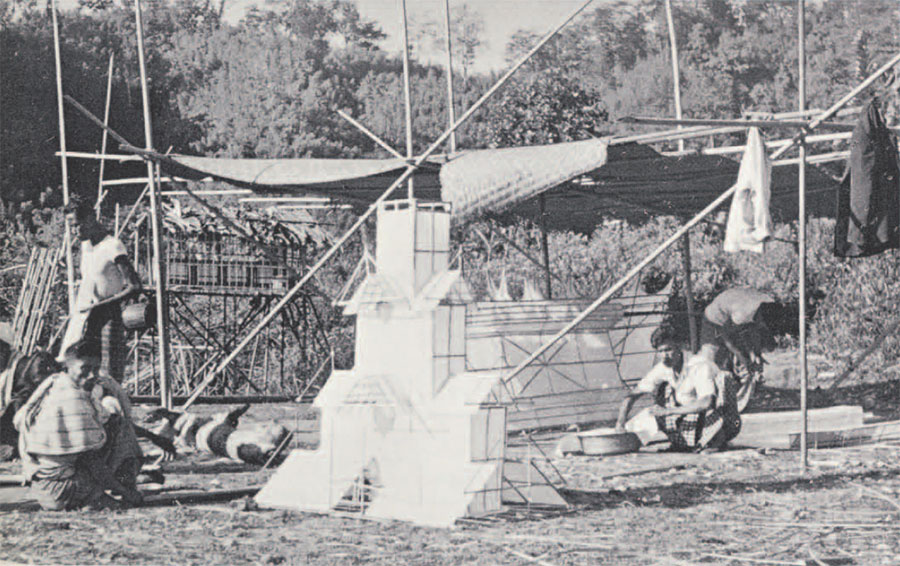

Thursday. The day was spent taking a twenty-mile walk to a nearby Mro village built a hilltop. Just before sunup the house began to stir. At six o’clock the mother and baby were up. She brought fire from the kitchen, as last night, for the hearth. It was chilly and everyone sat close to the hearth. Hot tea and hot rice were passed around. Then we set off on our walk. Our path took us along the river valley past ploughed fields growing mustard. Along the path we met a group building a white rice-paper khyong to burn in a cremation ceremony next to the river. The model was to take two days to make and stood three and a half feet high with a top piece six feet high. The frame was made of thin bamboo strips. Nearby was the coffin painted with white squares with blue frames on a red background. It stood on a platform five feet above the ground and was sheltered by a gabled roof. On top of the coffin rested an orange, two bowls, and a small round basketry table. At one end hung a special drum for the ceremony. At other points along the river we saw ashy areas marked by white prayer flags–scenes of previous cremations.

…On the way home, in twilight, we passed through a forest of cosmos plants standing over seven feet high! It was dark among the bamboo thickets and walking took on an aspect of a blind-man’s bluff until we stopped by the dead man’s coffin which was lighted by a lantern from which we lighted bamboo flares to carry. The two bowls were gone but the orange and drum remained. The khyong was now also painted blue and red. The bamboo flares made small circles of light and the night was pleasantly cool. We arrived back at the village at 7:15 and found our hosts already asleep, having given us up for the night…

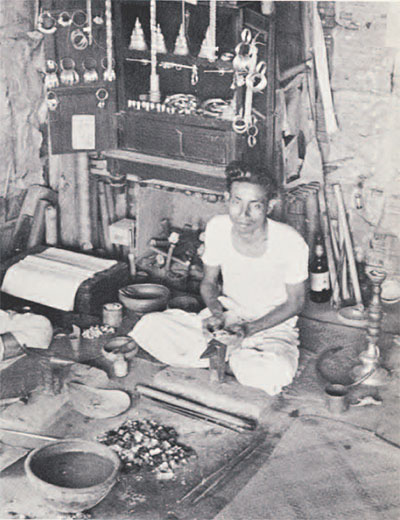

Monday. On my way to the boat I visited the main khyong in Banderaban. The priest, a commanding presence with his shaven head and saffron robes, is eighty-five years old. The white plaster khyong over which he presides contains a large room with four columns. At the far end are several statues of Buddha among small but elaborate shrines with inset glass, mother-of-pearl, and semi-precious stones. One of the little figures measures about eight inches high and has a traditional history dating back four to five hundred years. It is said to have come originally from Burma. Large white rice-paper umbrellas cover the figures. At the right hangs a row of gongs–some shaped like stylized khyongs. A conch shell and horn are also used. Outside one sees a long corridor of cells and cooking equipment and a big wooden chest. Inside the room along the west wall stand cabinets holding the extra robes of the novices. These are donated by private citizens who buy the cloth, have it stitched up and dyed orange, and then present it as a gift at various festivals. I paid forty-four rupees to have one made in the market. It comes in two parts: a lower skirt worn like a lungi, and an upper cape placed around the right shoulder, across the chest, then up over the left shoulder to hang down freely. Toward the front was a cabinet full of books and about fifty silver Buddhas. At the left stood a reclining couch and punkah (fan) for the old priest. At the entrance against this wall was a large throne and two smaller ones. Candles and flowers were offered before the shrines, and one had to remove the shoes before entering the temple courtyard.

Next we climbed the steep hill overlooking the khyong. The hill was topped by a stupa which is lighted at night by strings of electric light bulbs. At the floor of the hill lie the tombs of the wives and daughters of the Bohmongs. Inside the stupa’s white walls stood three brass Buddhas. The central one was about eight feet tall and covered with a saffron robe. Stretched across the ceiling was a white paper with a black painted inscription. I asked to take a picture and the priests insisted on straightening the Buddha’s robes. As they did so they also exposed the statue’s hands. There was an audible gasp. Generally speaking, novices, drawn from the villages for training, work in the gardens and around the building. Formerly there was a wooden khyong near the west end of the big tank near here but it wasn’t in good repair and the present Bohmong built the new one of concrete, plaster, and corrugated tin. All that remains of the older one is a patch of concrete flooring and a mound of bricks.

After saying goodbye at the khyong, we walked through the quietly busy market and climbed down the cliff to the cool river and Kyatung’s small dugout. Then began our return journey down the shadowy river already filling with fog and cold. Had a can of beans and bully beef for supper and fell asleep.