The Mediaeval custom, among people of rank, of placing a large saltcellar, called a salt foot, near the middle of a long dining table and seating the more honored guests above “the salt” with the less honored below, probably developed because of the enormous cost and consequent prestige value of the lumpy, brownish salt of the Middle Ages.

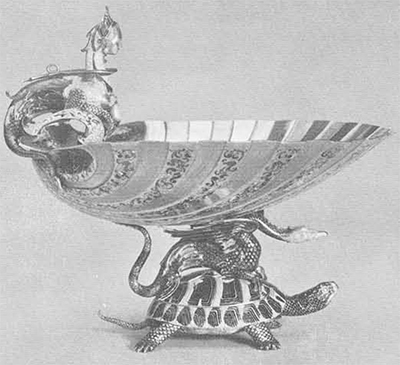

As far back as the eleventh century, the great salt mines of Wieliczka in Poland were worked by the local serfs and for many years these Eastern European mines were the principal source of this essential commodity. People who lived by the sea produced a certain amount by evaporation in salt pans, but never enough for the commercial demand. A carefully wrapped lump of salt, to be hammered into a coarse powder, was a noble gift in those days, and every great household possessed one or more elaborate saltcellars, of silver or gold, of pottery or porcelain, and sometimes ivory. One of the most celebrated saltcellars of all is that executed by Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571) for the Rospigliosi, a triumph of gold casting, now one of the most admired treasures of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

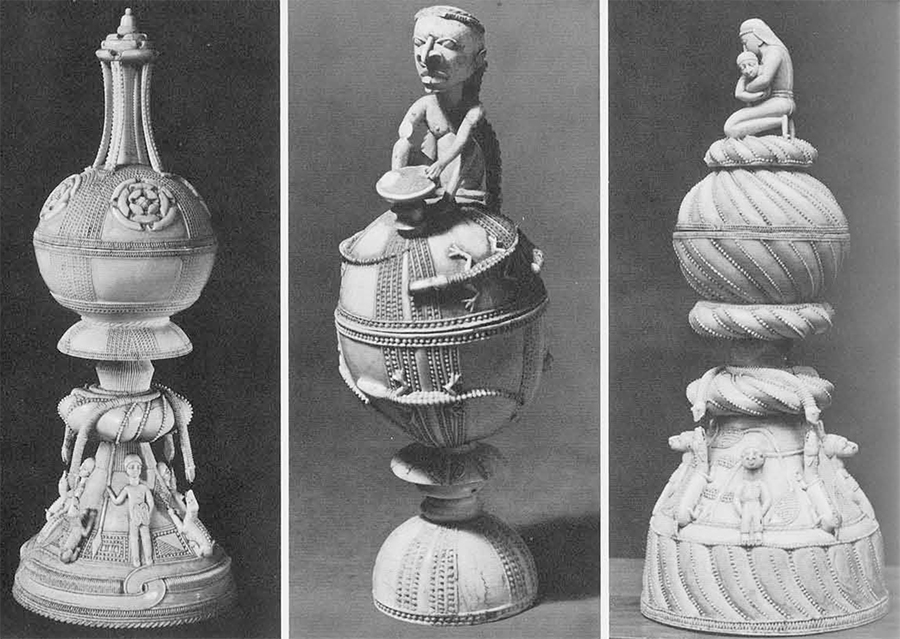

Saltcellars of ivory were rare, even in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, but above fifty are known in the museums and royal cabinets d’art in Europe. In the middle years of the nineteenth century, chiefly through the interest of Sir Wollaston Franks, Keeper of Antiquities, a dozen or so ivories of this type were acquired by the British Museum and correctly registered as saltcellars. As late as 1952, a heavily worn and richly patinated saltcellar of ivory came to the museum, and all of these cups, hunting horns, spoons, and forks are a hybrid style which has long escaped study. Sixty years ago, von Luschan in his Altertumer von Benin cavalierly pronounced them to be Bini work and illustrated several pieces found in German collections in his monumental tome. The collection in the British Museum now segregated in the Edward VII Gallery there, is the largest in the world, few of the European collections owning more than three or four pieces. William Fagg, in his book Afro-Portuguese Ivories, published in 1959, expresses the common consent of scholars that these ivories were made to Portuguese order by African carvers. While their elaborate Renaissance style is in a character favored by fifteenth and sixteenth century European craftsmen, and while a number of the pieces display the Portuguese arms, the ivory-working technique they exhibit, along with the representation of African Negroes and animals, is plainly African. They are all carved without the aid of a lathe, completely “by hand.” Their spherical compartments are so large that they must have been worked from extremely big tusks. In a few pieces, a broken or missing lid or foot has been turned out on a lathe by a later European craftsman, but the repair or replacement is always quite evident and of different technique from the original piece.

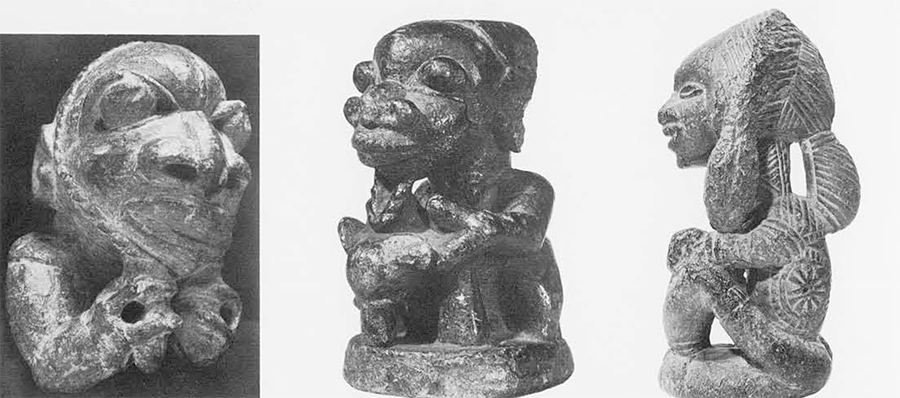

Since the publication of Afro-Portuguese Ivories, which merely isolated and defined the problem of exactly where the great ivories were made and by whom, Mr. Fagg’s researches show that most of the (at least three-quarters) are in the style of the Sherbro people of Sierra Leon, whose small soapstone figures, called nomoli, are said to represent agricultural spirits. Since the nomoli style (now extinct) was flourishing in the latter part of the fifteenth century and early in the sixteenth century, and since their carvers, the Sherbro people, were highly recommended to the Royal Court at Lisbon, according to old Portuguese records translated by Commander Texeira da Mota of Lisbon to carve the fine elephant tusks that, with gold and slaves, were part of the flourishing trade between Sierra Leone and Portugal in those centuries.

One of these are Afro-Portuguese salts is now on exhibition in the Entrance Gallery at the University Museum, on generous loan to us from the great collection of Mr. Jay C. Leff of Uniontown, Pennsylvania. There are very few of these beautiful creations in America. A handsome specimen, somewhat smaller than Mr. Leff’s, with a seated Negro on top of the hemispherical cover, is in the collection of Mr. and Mrs. N.M. Heeramaneck of New York; and another, with a mother and child as cover handle by a later hand, is in the Allen Memorial Art Museum of Oberlin College. In the three examples of salts known to me in this country all have hemispherical compartments for the salt, the top half of the sphere forming the cover. And all three have conical bases, that of the salt on loan to us being the most strikingly flared. While the design on this piece is plainly of European derivation, the African hand that carved it is shown in the four Negro figures in High relief on the base, two men and two women, nude to the waist but the men wearing European pantaloons and the women skirts. These figures, separated by four delicately carved snakes hissing at four snarling dogs, are quite certainly of Sherbro craftsmanship, and most exquisitely worked.On the art of Negro Africa, as a general rule, the impact of the European aesthetic has been only destructive, but in these beautiful Afro-Portuguese ivories we can see rare examples of truly successful hybridism in art.