The provincial centers of ancient Egypt were vital elements in its political, economic and religious systems and their remains reflect the continually changing pattern of the interaction of national and local influences. One component of these remains—the cemeteries generated by such centers—is in middle and southern Egypt, usually accessible and relatively well preserved (being on the low desert); they have often been excavated and recorded. The other components—the ancient town itself and its temples—are less well understood, because typically they are badly destroyed or inaccessible under modern towns and fields. At a few sites, conditions are better, one such being Abydos, where enough has survived of its long-lived town site and temple center to attract several excavators over the years. Most recently, the Pennsylvania-Yale expedition has worked at the site, from 1967 to 1969, and in 1977, with future seasons planned. The project is co-directed by William Kelly Simpson and the writer, the latter having directed the field-work undertaken to date and being responsible for organizing the publication of the results so far achieved.

The specific archaeological topography of Abydos as a whole was shaped by its primarily religious role, the chief features of which are well known although much of this vast site (which occupies about 13.5 square kilometers) remains unexplored, despite a history of excavation and epigraphic recording going back to the early 19th century. Its earliest importance was as a royal center, at which the late prehistoric kings of southern Egypt and subsequently of the first dynasty to rule over a united Egypt (ca. 3100-2890 B.C.) were buried. During Dynasty II, the Memphite region became firmly established as the royal center, and the royal cemeteries from Dynasty III onwards were located there; but Abydos retained a national significance because it became, during the later 3rd millennium B.C., a major cult-center of the god Osiris. Osiris was revered throughout Egypt because, as lord of the dead, he controlled the destinies of all Egyptians in the afterlife. Equally important, his myth was an essential part of the Egyptians’ concept that their chief gods. Ra (the sun-god) and Osiris, regularly triumphed over the chaotic supernatural forces which perpetually threatened the existence and stability of the universe. Annually, the myth of Osiris’ death and resurrection was celebrated in an elaborate processional ritual at Abydos, and its mostly arid landscape of sand-covered gravels and marls was therefore suffused with great symbolic and emotional significance.

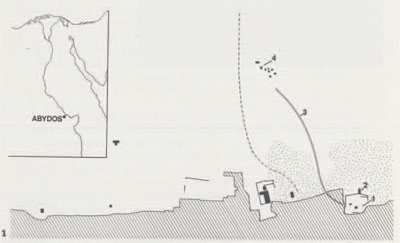

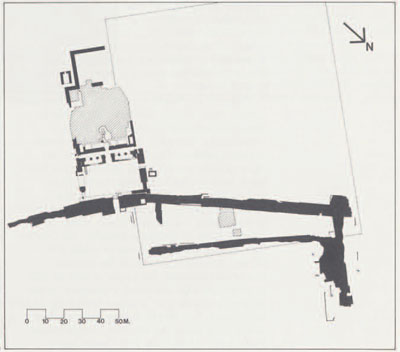

The Pennsylvania-Yale excavations are located in the northwestern (and oldest) section of Abydos. (The southeastern sector, containing the memorial temples of several 2nd millennium kings, developed later.) Between the royal tombs of the southwest, and the ancient town and temple center on the northeast, stretches a vast cemetery bisected by a shallow desert valley which was kept free of intrusions until Hellenistic and Roman times. This valley was apparently the processional way linking the Osiris temple with the supposed tomb of Osiris, which in fact was one of the early royal tombs. Our excavations are focused on an area particularly revealing for the direct interrelations between the chief components of the site, the junction between cemetery zone and the town and its temples.

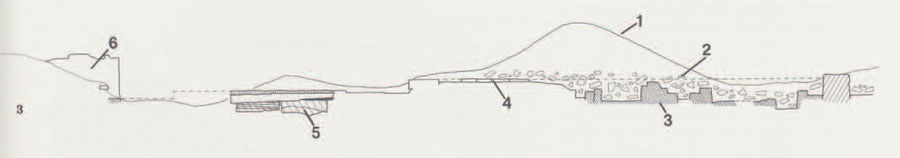

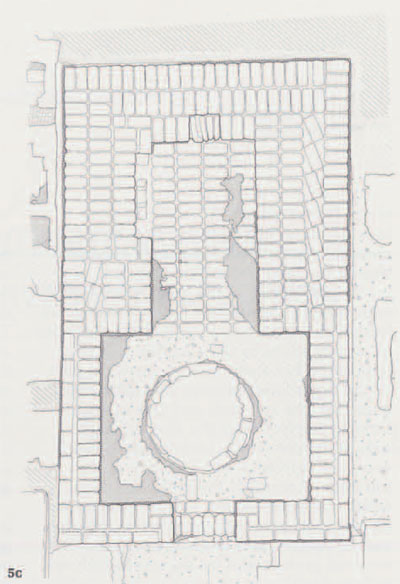

The main area of excavation was overlain by large spoil heaps thrown up by a plundering dealer (Anastasi; early 19th century), Mariette’s poorly recorded excavation of 1861 and Petrie, in 1902-03. Beneath these were the shattered remains of a once large limestone temple dedicated to Osiris by Ramesses II (ca. 1304-1237 B.C.), which must have survived for a long time before being destroyed so that its stone could be reused. Later cemeteries lie on its northwest (and probably southeast), dating as late as Dynasties XXVXXVI (ca. 747-525 B.C.) and probably later; but tombs never intruded into the temple or its forecourt. Moreover, a great Roman enclosure wall of the main Osiris temple, (which lay northeast and downhill from the Ramesses II temple] cut through the Ramesside brick pylon but had a gateway precisely above the entrance to the Ramesses II forecourt, suggesting that access to the Ramesses H structure was still desired.

The ancient town mound of Abydos was largely removed in the past, probably by peasants seeking to reuse its fertile, organically rich soil, but along the southwestern edge of the mound (where our excavations are located) preservation has been better. Old Kingdom strata, (later 3rd millennium B.C.] possibly occupational, run under the Ramesses II forecourt and perhaps the temple itself, while in the nearby Kom el Sultan a peculiar configuration of late period enclosure walls preserved a large segment of the mound. Mariette removed the upper levels of this segment (which included Ptolemaic occupation, according to ostraca found by us in his dump], but strata dating from earlier times to at least the Second Intermediate Period (ca. 1730-1570 B.C.) have been recorded by Barry Kemp, while we ourselves have excavated part of an Old Kingdom stratum with substantial houses in Kom el Sultan. Future work will enable us to reconstruct the history of this fragment of the old town in more detail.

Especially important for reconstructing the topography of Abydos, and for Egyptian religious history in general, was our discovery of a complex of mud-brick chapels under the Ramesses II temple. These chapels are dated to the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2040-1740 B.C.) by rare in situ inscriptions, by others scattered through the debris and, above all, by literally thousands of sherds from discarded offering jars and bowls. They are in fact the first scientifically excavated and recorded examples of private ‘cenotaphs’ or memorial chapels, referred to in Middle Kingdom texts from Abydos but never described in detail there. Such chapels probably stretched in a belt from the entrance to the processional valley northwest along the low desert crest overlooking the Osiris temple, but our section of them must he the best preserved, for it was sealed off for centuries by Ramesses’ temple; subsequent exposure and repeated plundering still left our chapels structurally intact.

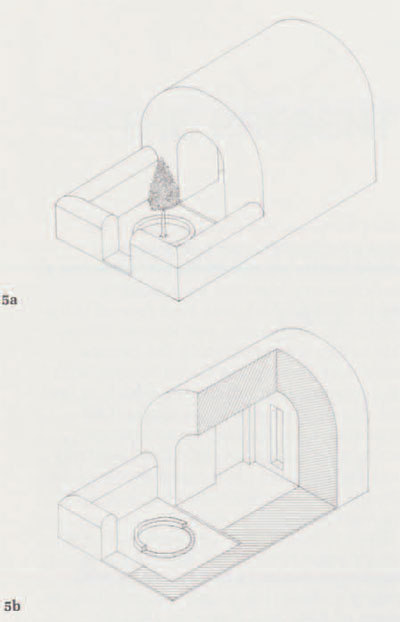

The larger chapels are of two types. Some are single barrel-vaulted chambers, originally containing stelae and statuettes; they were fronted by low-walled forecourts, sometimes with one or two tree pits. Others are square, solid structures of which the upper sections (cut away when the Ramesside builders levelled the site) probably had stelae set in them. The spaces between the large chapels are packed with smaller ones, due to an accretion process covering a long time span. This is the archaeological equivalent of a process observed by Simpson amongst the Middle Kingdom inscribed material recovered by Anastasi, Mariette and others at Abydos. Many of these inscriptions ‘cluster’ together by referring to interrelated individuals, and each ‘cluster’ must have been originally housed in an architectural complex similar to ours.

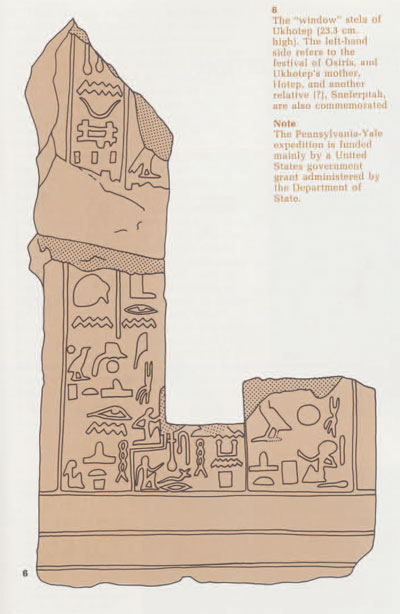

The function of these chapels was not funerary. There is no space for burial shafts, no subterranean chambers exist beneath the chapels and no trace of the typical Middle Kingdom funerary equipment was found. The chapels’ purpose was to enable those commemorated in them to share in the offerings made at the Osiris temple and, above all, to participate in perpetuity in the great annual festival reenacted along the processional way. We found in situ proof of this desire which had previously been known from a number of uncontexted Abydos stelae. A small stone stela had framed the ‘door’ of a small chapel and through it a statuette had peered out. The text on the still largely surviving left hand side of this stela originally read: “Kissing the ground before Khenty-Amentiu (Osiris)” and “seeing the beauty of Wepwawet at the first coming forth” “by the revered one, Ukhhotep” (translation by the author). These phrases refer to participation in the great Osiris festival.