In February, 1967, a combined expedition of the University Museum and Yale University commenced excavations at Abydos in Southern Egypt, the first work undertaken by the University Museum at a major Egyptian site since 1956. The Museum has, of course, a long record of excavation in Egypt, beginning in 1906 when Eckley B. Coxe, Jr. first began to support the Museum’s work there. The most recent Museum excavation at a major Egyptian site was at Mitrahineh (ancient Memphis) in 1955 and 1956 under the direction of Professor Rudolf Anthes; subsequently, the Pennsylvania-Yale Expedition was formed under the direction of Professor William K. Simpson, Professor of Egyptology at Yale University, in response to the UNESCO appeal for excavation in those parts of Egyptian and Sudanese Nubia to be flooded by the new Assuan dam. The Expedition spent the seasons of 1961 and 1962 excavating a large concession in Egyptian Nubia and carried out a systematic study of the remains of all periods (Pharaonic to Christian) present in the concession, the publication of which has now been half completed.

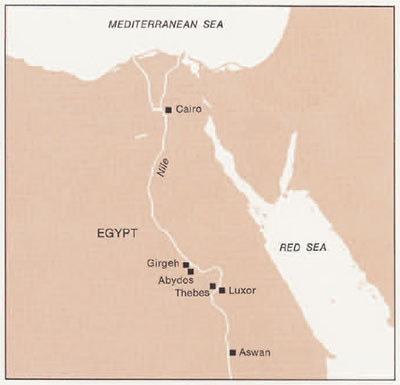

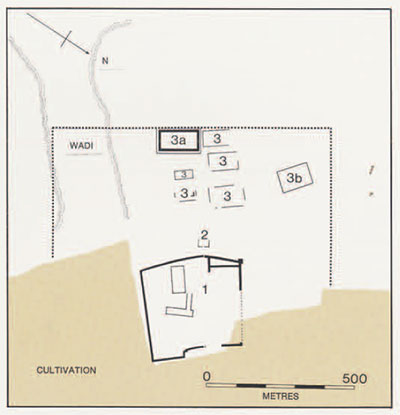

The government of the United Arab Republic has stated that any institution participating on a major scale in the Nubian campaign would be granted a site in Egypt after the campaign had closed if one was desired. The Pennsylvania-Yale Expedition and its supporting institutions were naturally anxious to continue work in Egypt and I, having joined the University Museum staff in 1964, carried out a site-survey from December, 9 to January, 1966 covering some thirty major sites in Northern and Southern Egypt. As a result of this survey the Expedition applied for a concession at the site of Abydos in Southern Egypt, specifically requesting for reasons discussed below the area outlined on the map. This concession was granted to us by the government of the United Arab Republic in February, 1967.

As Professor Simpson, the Expedition Director, was prevented by academic and other responsibilities from leaving the United States, I, as the Associate Director, organized and directed this season’s excavations. The members of the Expedition arrived in Cairo in January, 1967; by February 14, we were established on the site and excavation commenced on February 17. Excavation ceased on May 2 and on May 5 we left for Cairo, where arrangements for next season were made.

Working with me for the greater part of the season were Mr. Barry Kemp, Assistant Lecturer in Egyptology at the University of Cambridge, England and Mr. Abdullah es Sayid, Inspector of Antiquities for the Governorate of Sohag, who had been assigned to the Expedition by the Antiquities Service. Mr. Kemp was an extremely competent and cheerful field worker and, having worked for some years on preparing the results of the excavations (1906-09) of John Garstang at Abydos, had a detailed knowledge of earlier work on the site which contributed considerably to the success of this season. Mr. es Sayid greatly facilitated our work by his enthusiastic participation in organizing the building of an expedition house, in the excavations, and in the recruitment of labor. The continual assistance of Dr. Mukhtar, Director General of the Antiquities Service and of his officials throughout the season is gratefully acknowledged. Mr. Kemp had to return to England in April and I was joined for the last three weeks of the season by Mr. Lanny Bell, a graduate student of the University of Pennsylvania carrying out epigraphic work at Luxor, who assisted me valiantly in the hectic process of closing down the excavations.

Excavation in Egypt is, of course, still largely carried out by means of laborers who remove the debris with hoes and boys who carry it away in baskets to be dumped. Our original labor force consisted of ten Guftis (workers from the town of Guft, in Southern Egypt, who have had long experience of archaeological excavations) and twenty basket boys. It soon became apparent that the area chosen for excavation was covered with large heaps of debris deposited there by plunderers and earlier excavators and we rapidly augmented our labor force to a maximum of sixteen Guftis and some 120 local laborers and boys in order to remove this archaeologically meaningless material as rapidly as possible. In this we were greatly aided by the Antiquities Service, which lent us a Decauville railway which we repaired and maintained.

The Expedition’s work was supported by a grant from the United States Government of Public Law 480 counterpart funds in Egyptian pounds and by dollar contributions from the Coxe Fund of the University Museum and from Yale University (through a grant from the Bollingen Foundation to the Peabody Museum).

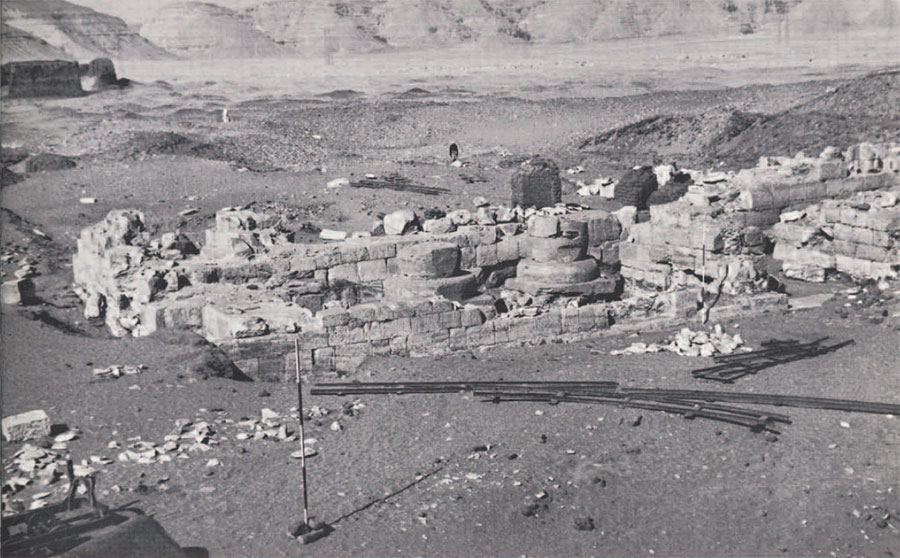

This season the Expedition concentrated on the comparatively simple task of beginning the clearance of a structure known as the “Portal of Ramesses II.” This building is small and the large masses of debris covering it consist of loose material the removal of which could be satisfactorily supervised by our small staff. The so-called “Portal” is one of the minor mysteries of Abydos; only its exposed, four-columned portico has ever been examined in detail. The French excavator, Mariette, correctly dated the “Portal” to Ramesses II, publishing a brief description with a small plan; later, Flinders Petrie, after small-scale clearances in 1902 and 1903, published a better plan of the portico (still inaccurate in detail) and suggested that the whole structure might be a ceremonial gateway into the cemetery.

We first cleared the entrance in the southwest wall of the “Osiris Temple Enclosure” (see below) in order to run the Decauville railway to the interior of the Enclosure where we will dump on the area exhausted by the earlier excavations of Petrie. On March 3 we commenced excavation in the “Portal” area; in general we removed only the large heaps of debris overlying the structure, reserving complete excavation for the next season, but the portico and certain areas of the northwest side of the “Portal” were examined in more detail.

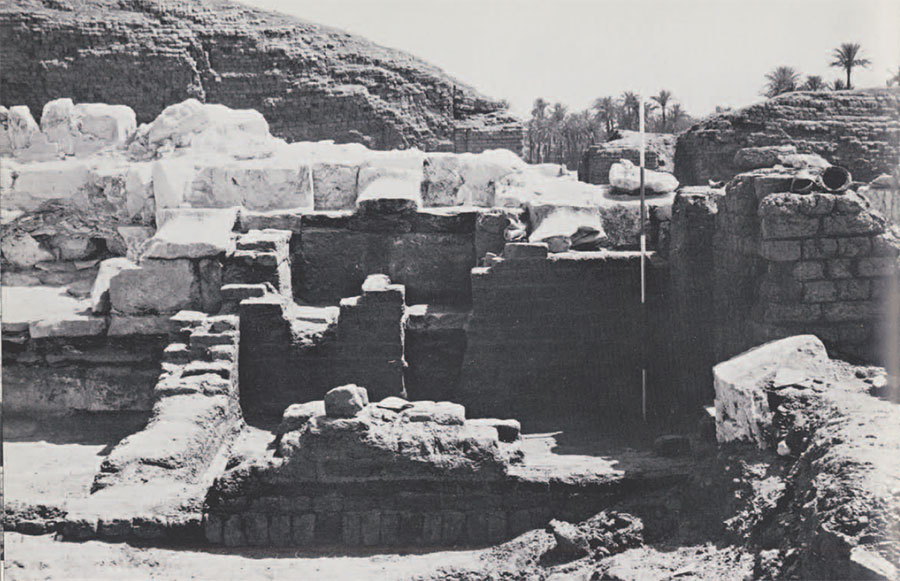

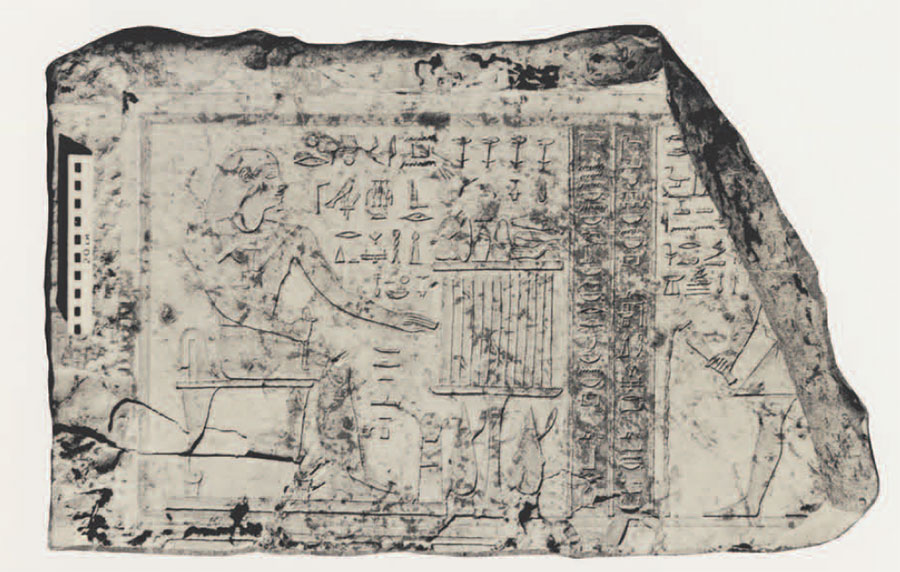

It is now clear that the “Portal” is a temple and not a ceremonial gateway. The building has been reduced by stone robbers to the lower levels of its walls and to foundations, but it is littered with loose blocks, many with fragments of scenes and texts, shattered Osiride statues (statues representing the temple’s royal builder in the form of Osiris) and fragments of architectural elements. This debris, which we carefully collected, may enable us to reconstruct in drawings much of the original appearance of the temple.

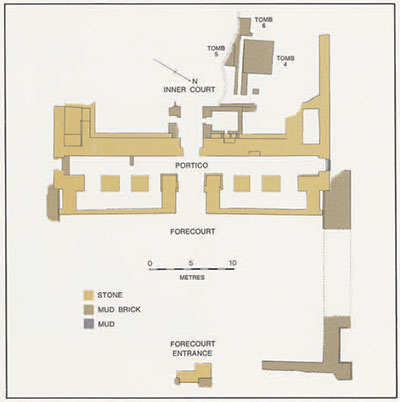

The inscriptions surviving on the walls and loose blocks show that Ramesses II (1304-1237 B.C.) built most, if not all, of the temple and that it is dedicated to Osiris, Horus, and Isis and gods associated with their cult. A few loose architectural elements and fragments bear the name of Ramesses’ predecessor, Seti I, but as it is certain that the surviving walls contain inscribed blocks taken from other buildings it cannot be claimed yet that Seti was the founder of the temple.

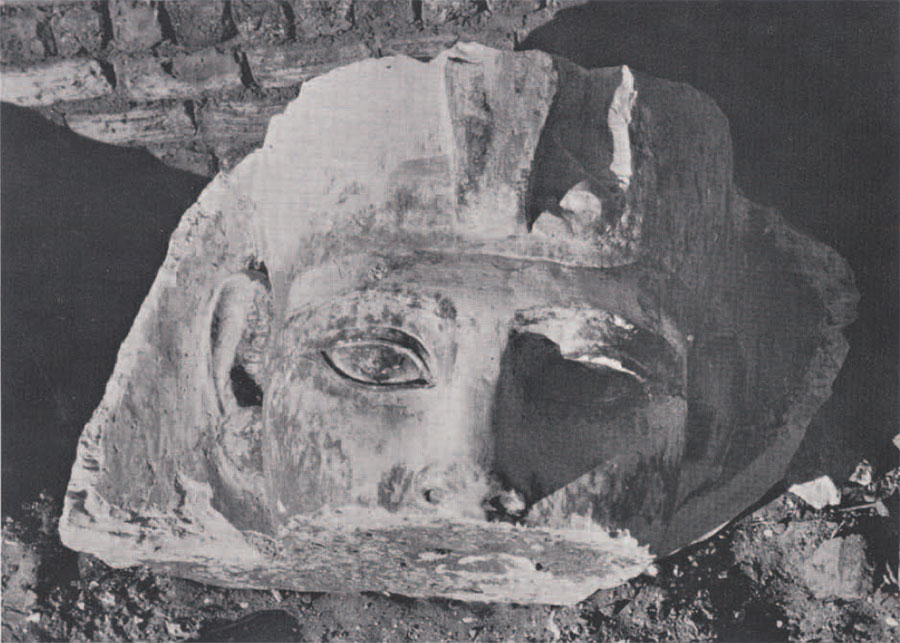

The temple had a forecourt with mud-brick walls and the batter on a preserved wall face suggests that a brick pylon stood on the northeast. The limestone paving of the forecourt entrance was found in situ below the entrance in the southwest wall of the “Osiris Temple Enclosure” but the Enclosure wall at this point is later than the temple, for its foundation trench cuts through the temple pylon. The temple proper is built of small limestone blocks with sandstone used in a few places. A line of offering bearers and gods is carved on the front wall, baboons adoring the names of Ramesses are carved on the walls of the portico entrance, and texts and fragments of scenes are preserved on other walls. Southwest of the portico are the remains of what is probably an open court with, running around its walls, a platform on which Osiride statues (the feet of a few were found in situ) were arranged in an unusually complex pattern. In this court we found the fragments of a colored, over-lifesize royal statue in limestone. Although we do not yet have enough of the plan to make a detailed comparison with other New Kingdom temples our temple seems to be of an unusual type, designed perhaps for a special cult practice.

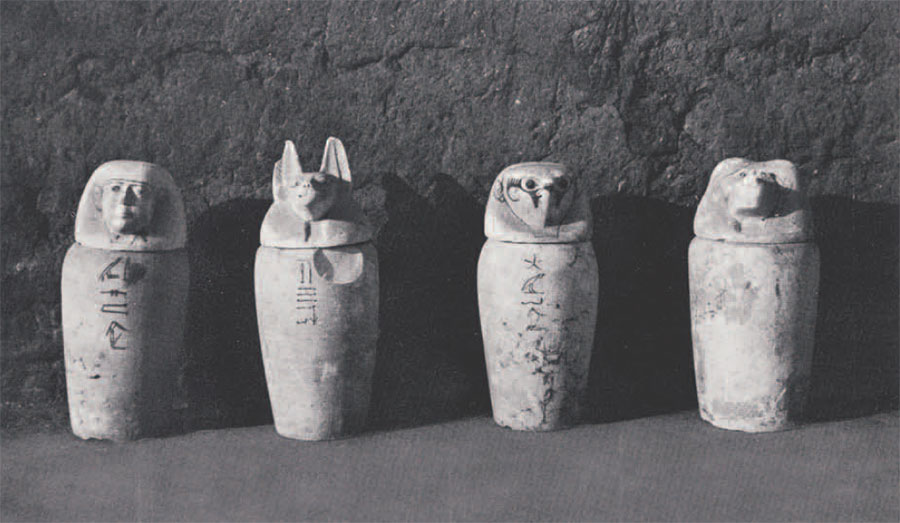

We have not yet encountered the Old Kingdom (c. 2700-2200 B.C.) town rubbish Petrie claimed to have found under the “Portal,” but we have found underlying brick walls which may belong to an earlier structure or to the temple’s foundations. The beginning of the temple’s destruction cannot yet be dated; the brick-walled rooms flanking the inner court entrance and more particularly the apparently later tombe (tombs 4, 5, 6) built in and around the temple, may eventually contribute to the solution of this problem. The tombs within the temple were reburied until the next season, but tomb No. 3, immediately northwest of the forecourt, was excavated. It was a big, perhaps family tomb, largely undisturbed and containing nine burials, of which the earliest may date to Dynasty XIX or XX. The burial furniture was comparatively poor, but included a fine set of limestone canopic jars while some of the decayed coffins still bore the names of their owners.

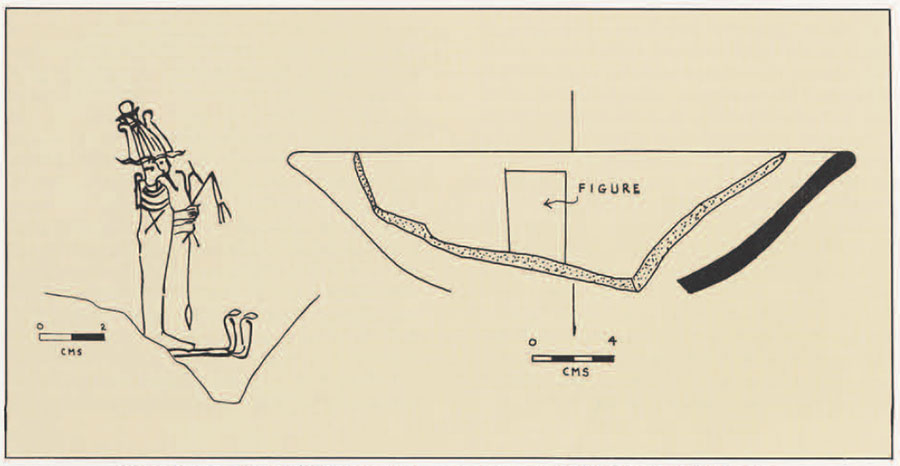

Over six hundred objects were catalogued this season, coming mostly from the overlying debris which was certainly loose debris left by plunderers and perhaps the earliest excavators. These objects are very varied in nature; some are of intrinsic importance, others give information on the types of activity current in the area at various periods.

There is a large amount of inscribed material which has not yet been studied in detail. This material includes the names of a king Senusret, Amenemhet III, Amenhotep III, and Horemheb on various objects, six intact or largely intact funerary stelae, fragments of over thirty other stelae, a large and well carved funerary stela on a lintel from a late period tomb, and fragments of a number of inscribed statues. Numerous ostraca include at least twenty in hieratic and sixty in demotic, with a large remainder still to be identified. Clearly coming from plundered graves are fragments of coffins and small mud shawabtis and, less certainly, mud bricks bearing the stamp impressions of “The Overseer of the Treasury, Amenhotep, justified” or “The Osiris, Vizier and Mayor of Thebes, Pesiur, justified.”

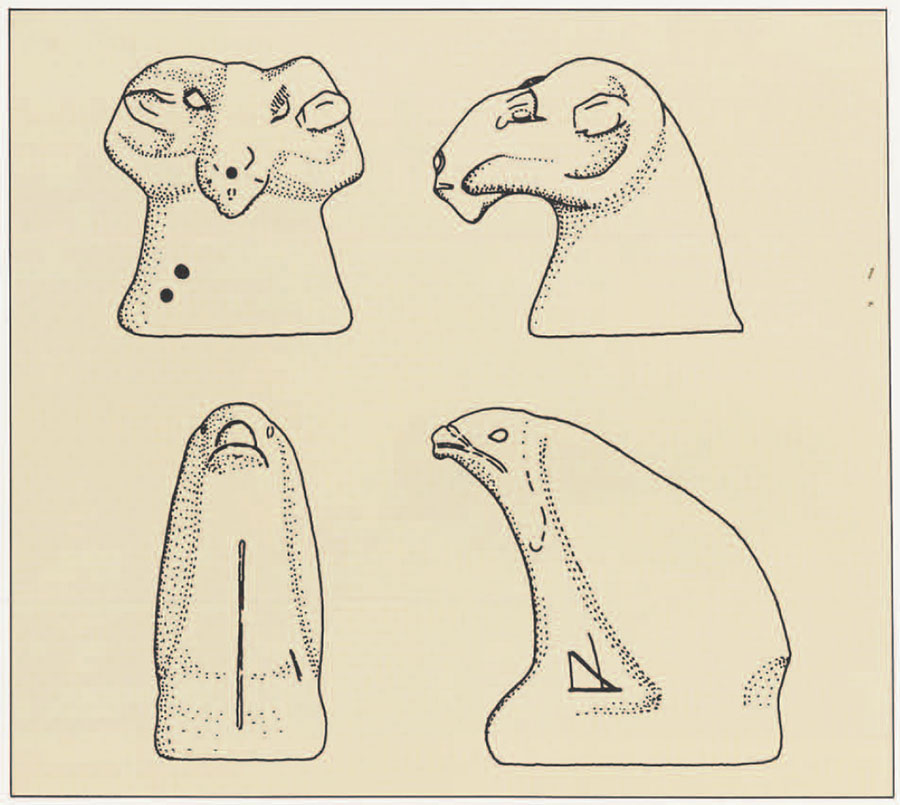

Two categories of objects require special mention as they have not, to my knowledge, previously been found in Egypt. The first consists of a large number (50) of sherds which had originally belonged to red or brown ware bowls all of the same shape. What was unusual about these bowls was that the interior had been inscribed in black or white ink with drawings of various gods, sometimes standing on boats and sometimes standing with their names written in cursive hieroglyphics. Some sherds from similar bowls had a single line of hieratic text. The second category consists of small unbaked mud figures, fairly carefully modelled. Ram heads formed the largest group (30), cobras, some with white ink texts on the front, the second largest (10), and vultures the smallest (5). These animals in Egyptian religion are associated respectively with the god Amun and the goddesses Renenutet and Mut. Both categories of objects appear to be votive but their exact function and significance are not yet clear.

During this season we also organized and supervised the building of a large mud-brick and baked-brick Expedition house containing twelve rooms and a storeroom for the antiquities. The house is three-quarters finished and will be completed at the beginning of next season, when it will accommodate our greatly increased staff. Next season we intend to complete the excavation of the “Portal” and turn our attention to some of the major problems which attracted us to the site of Abydos.

Our concession at Abydos measures approximately 950 by 800 meters and although this represents a comparatively small part of the total area of ancient ruins at Abydos, it was carefully chosen for several reasons. Firstly, the Expedition wishes to study the number of problems of general interest to Egyptology. We plan, for example, to establish a chronological sequence of the commonest archaeological material (pottery, seals, etc.) characteristic of each period of Egyptian history, based on a study of stratified occupation debris instead of the rather limited material from cemeteries which has been used hitherto. We hope also to gain further information on the development and organization of Egyptian towns; in Egypt only three Pharaonic towns have been excavated in detail, and these are specialized in function and chronologically narrow in date. Finally, the study of cemetery development has played a large part in reconstructing Egyptian history and we should like to test some of the hypotheses and conclusions arising from this study.

Earlier excavations indicate that out concession is promising for these purposes. A large (325 x 300 meters), thick-walled enclosure of sun-dried mud-brick, known as the “Osiris Temple Enclosure,” contains the ruins of several temples, ranging in date from about 3000 to 360 B.C., and of the towns which developed around them. A considerable mass of exposed and stratified occupation debris spanning the Old, Middle, and probably New Kingdoms is readily accessible, and houses and debris of the late prehistoric, Early Dynastic, Old and New Kingdoms were located and partially excavated by earlier excavators. As this part of the concession is at the same level as the alluvial plain, sub-surface water will be a problem requiring the use of pumps. Behind the “Osiris Temple Enclosure” the ground rises sharply and the rest of the concession is well above sub-surface water level. Southwest of the “Enclosure” stretches a great cemetery (extensively plundered) with burials of all periods and dominated by two ancient mud-brick enclosures; one, called today the “Shunet ez Zebib,” is empty, the other is occupied by a modern Christian village.

Secondly, the Expedition hopes to make a major contribution to the understanding of the complex history of this important site by systematically excavating what appears to be historically the most important part and by studying the great mass of information already gathered by previous excavations. it is surprising that the considerable amount of excavation already undertaken at Abydos has left so many gaps in our knowledge, but results were affected by the inadequate nature of the earliest work and by the sheer size of the site. The site of Abydos, the importance of which was already known from Greek and Roman writers, had already been identified by the end of the 18th century A.D. and the visible monuments several times described, before excavation began in 1858.

During the first phase of excavating (1858- 1898) a wide area was covered by Auguste Mariette and subsequently, E. Amelineau, but their work was poorly controlled, often superficial and inadequately recorded and published. The second excavating phase (1899-1926) covered an even larger area and was carried out by British Egyptologists, of whom the most active was Flinders Petrie. The work of this phase was well controlled, recorded, and published, but resources were limited, so only selected areas could be cleared. Several important excavations carried out by the Egyptian Antiquities Service at various points on the site have been confined to comparatively small areas.

Consequently, probably some three-quarters of the total remains of Abydos are still uninvestigated. Within our present concession the southwest part of the cemetery has been excavated but not exhaustively, while the northeast part of the cemetery has not been touched since Mariette’s day. Apart from one area intensively excavated by Petrie and some superficial excavations by Mariette, the interior of the “Osiris Temple Enclosure” remains unexcavated, while the northwest part of our concession has received little previous examination.

A brief review of the known history of Abydos will indicate both its importance and some of the problems we plan to investigate.

Both ancient Egyptian and classical sources make it clear that Abydos was chiefly a religious and not political or economic center. Geographically, it was not especially well favored. All the politically and economically important towns of Upper Egypt stood close to the Nile, the main means of communication, but the ruins of Abydos today lie on the low desert adjoining the cultivation about six miles west of the Nile. There is no evidence that the Nile ran closer to Abydos in ancient times, although the town, like many in Egypt, was linked to the river by a canal. Moreover, historical records show that the principal political and economic activities of the Eighth Upper Egyptian nome (province), in which Abydos lay, were initiated and controlled by the nome capital, This, which significantly was probably located near modern Girgeh, on the Nile bank. Routes from the Eighth nome link it to the economically important trade route running through the Libyan oases to the Sudan, but there is no particular evidence that Abydos played any special part in developing or controlling this route.

Abydos certainly benefited from being in one of the largest and most fertile nomes in Upper Egypt. The alluvial plain in this part of Upper Egypt is particularly wide, varying from 25.5 to 17.3 kilometers, while the govenorate of Sohag, in which the nome lay, is one of the leading producers of agricultural produce in Egypt. How large the town of Abydos, situated at the very edge of the cultivation, was at various periods is as yet unknown. The bulk of the visible remains consists of cemeteries spread over a barren plain of low desert, beyond the reach of the Nile flood and the irrigation system, and enclosed within a great desert bay flanked by high, steep, limestone cliffs.

Abydos’ original religious importance was apparently due to the kings of Dynasty I (traditionally of Thinite origin), who succeeded in about 3100 B.C. in uniting and ruling the two formerly separate Kingdoms of Upper and Lower Egypt for the first time in recorded history. Large, tomb-like structures at Abydos (excavated 1897-1901) date individually to nearly all the kings of Dynasty I and to two kings of Dynasty II. In recent years they have been regarded by some as cenotaphs, since the apparently real tombs of the Dynasty I kings have been discovered at Saqqara near Memphis, the administrative capital of Dynasty I Egypt. However, previous excavators within our concession revealed the remains of several large mud-brick structures dating to Dynasties I and II (the best preserved being the “Shunet ez Zebib”) which may well be forms of royal funerary temples and which, as Mr. Kemp has recently demonstrated, would prove the true royal tombs of Dynasty I to be those of Abydos. Throughout their history the Egyptians certainly regarded Abydos as having a special connection with their earliest historical kings; completing the investigation of these possible temples is one of our aims.

It was during Dynasty I, if not earlier, that the chief temple area of Abydos was founded. Within the “Osiris Temple Enclosure” (the present walls of which are very late, probably post-Ramesside in date), Petrie found a Dynasties I and II temple, and partially excavated a late prehistoric-Early Dynastic town site and rich Dynasty I cemetery. Throughout Egyptian history the Enclosure area contained temples renovated or rebuilt at intervals, while towns developed around them. The most continuously preserved archaeological record of Abydos’ history, therefore, lies within our concession.

The other, and principal cause of Abydos’ importance was its reputation as the major cult-center of the god Osiris. By about 2000 B.C. the original god of Abydos, the dog-shaped funerary deity Khentamenty, had been absorbed by Osiris, apparently in origin a north Egyptian god, and thenceforth most activity at Abydos was connected with the cult of Osiris and the gods especially associated with his myth.

This myth, of which the main elements appear not to have changed throughout Egyptian history, related that Osiris was originally a living king of Egypt; iconographically he is usually shown as a man wearing a tall crown and grasping the crook and flail, symbols of kingship. Killed and dismembered by his envious brother, Seth, Osiris’ body was re-assembled (and is usually depicted as wrapped in linen like a mummy) by his sister Nepthys and his wife Isis. Isis miraculously conceived and bore Osiris’ son Horus who eventually fought and defeated Seth and rightfully claimed Osiris’ earthly kingdom. Horus then re-endowed his father’s body with a supernatural life so that Osiris could function as ruler of the kingdom of the dead.

Egyptian beliefs and rituals were strongly affected by Osiris’ myth. Osiris had to be especially honored at the god who ruled one’s fate after death. In addition, by basing funerary rituals on his myth the Egyptians hoped that the dead would be identified with OSiris and receive a supernatural life similar to his, which would enable their bodies to function in and enjoy the after-life.

The Egyptian kinship, with its strong emphasis on legitimacy, had a special link with the Osiris cult. The relationship between a living king and his predecessors, especially his immediate predecessor (usually his father) was held to be parallel to the relationship between Horus and Osiris. In honoring Osiris an Egyptian king was honoring also his ancestors, each of whom in this context was also Osiris, and secured by his filial devotion the assurance of a prosperous reign.

Our excavations should yield further information on the development of this royal devotion since we know from Petrie’s excavations in the “Osiris Temple Enclosure” and from textual sources that during the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms extensive royal building programs were carried out there. Elsewhere at Abydos, kings also emphasized their link with Osiris. The temples and pyramids of Senusret III (1878-1843 B.C.) and Ahmose (1570-1546 B.C.) in southern Abydos, the magnificent and well preserved temple and false tomb of Seti I (1318-1304 B.C.) and the large temple of Ramesses II (1304-1237 B.C.) are all, in effect, cenotaphs or dummy funerary complexes associating their owners closely with Osiris.

Similar devotion and interest was shown by private persons and the vast cemeteries of Abydos (of which only a part falls within our concession) cover all periods and all degrees of wealth and station. Consequently, they are an index to the funerary customs and archaeology and to the relative prosperity of the various periods of Egyptian history. Although considerable excavation has been carried out on some areas, a detailed analysis of the chronological development of these cemeteries has not been attempted. We hope to provide at least a basis for such a study by our excavations and research.