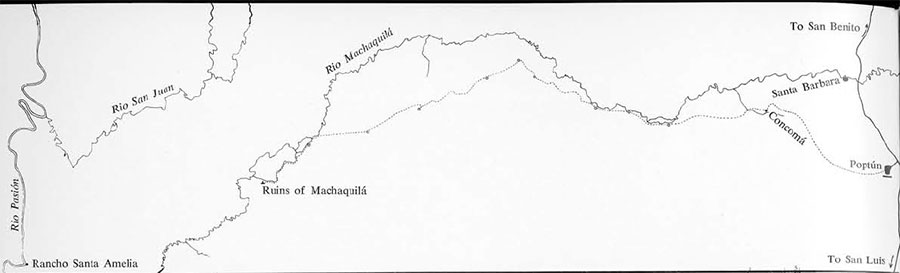

Any student of the Maya civilization will be aware of how incomplete a record there is of the ancient ceremonial centers of this people; quite large areas of the archaeological map are perfectly blank, and are likely to remain so for a considerable time, especially as there is no organized effort to correct the situation. In view of this I have spent time over the past four years following up stories of newly encountered ruins in the Department of Peten, Guatemala ( region that is best known, of course, for the great ruins of Tikal). It was a uniquely favorable time to do this, because petroleum geologists were intensely active in Peten, criss-crossing the jungle for seismic and gravity surveys, and investigating surface geology; also building camps, heliports, and so on. This massive campaign proved to be a failure as regards oil, but it did yield a number of “new” ruins as a by-product. (Hitherto, nearly all reports of ruins had come from chicle gatherers, never a very precise source of information.)

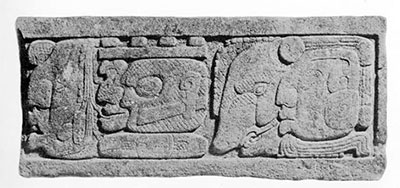

I made a tour of the oil companies’ offices in Guatemala City in order to question anyone who had been in the field. In this way I heard that Alfonso Escalante, of the Union Oil Co., had come across ruins midway between Poptun and the River Pasion, finding there some beautifully carved stones. Three of these had been brought out by helicopter, and I was shown one of them: one glance at it, and I was resolved to visit the site. For this was clearly part of a hieroglyphic stair; and who could tell how many other monuments and inscriptions might not be lying there, in that most inaccessible and least explored part of Peten?

The remoteness of the place was rather forbidding to me then, and I confess that for two years I was vaguely hoping to be wafted there by helicopter, as I learned much later Linton Satterthwaite had been (in 1958m but maddeningly for him, for a stay of only 15 minutes!). By 1961 I had gained some experience of travelling in the jungle, and the journey seemed less formidable; in any case, the helicopter patch near the ruins would have become hopelessly overgrown by then. And so in May of that year I set out on foot from Poptun with four men and a cargo mule for a preliminary reconnaissance. Two of my men had been employed by Union Oil to cut trails for geologists; thus we were not completely in the dark, and in fact only once went wrong–and then we wasted a day struggling through terrible little valleys with vertical rock walls (actually very large sink-holes), an experience that gives me real sympathy for Cortes, that time he was lost in similar terrain.

After five days we arrived at the ruins, which stand on the south bank of a branch of the River Machaquila that is dry at that time of the year. In the four days that our limited food stores allowed us to stay, I could do no more than carry out a lightning survey with compass and tape, and make a record of two of the stelae we found there. There were at least eight more carved stelae, all lying face downwards (what luck!), some well-preserved walls of extraordinarily fine veneer masonry, a vaulted chamber–the first to be encountered in southern Peten–and a large carved altar still supported by four cylindrical stone legs, which I espied under a tangle of vines and leaf-mould at the very moment we were leaving for camp on the fourth day. I would have to return the following year…

In October 1961, Hurricane Hattie devastated Belize, and passed on to spend its force in Peten. Poptun I knew had suffered badly, but no one could tell me to what extent the forest was affected over to the west. The wonderful aerial photographs of Peten taken the following March for the Guatemala Director of Mapping would have settled the point; but perhaps it was well that the prints covering just this region happened not to be available when I had asked for them–had I seen them, I should never have attempted the trip!

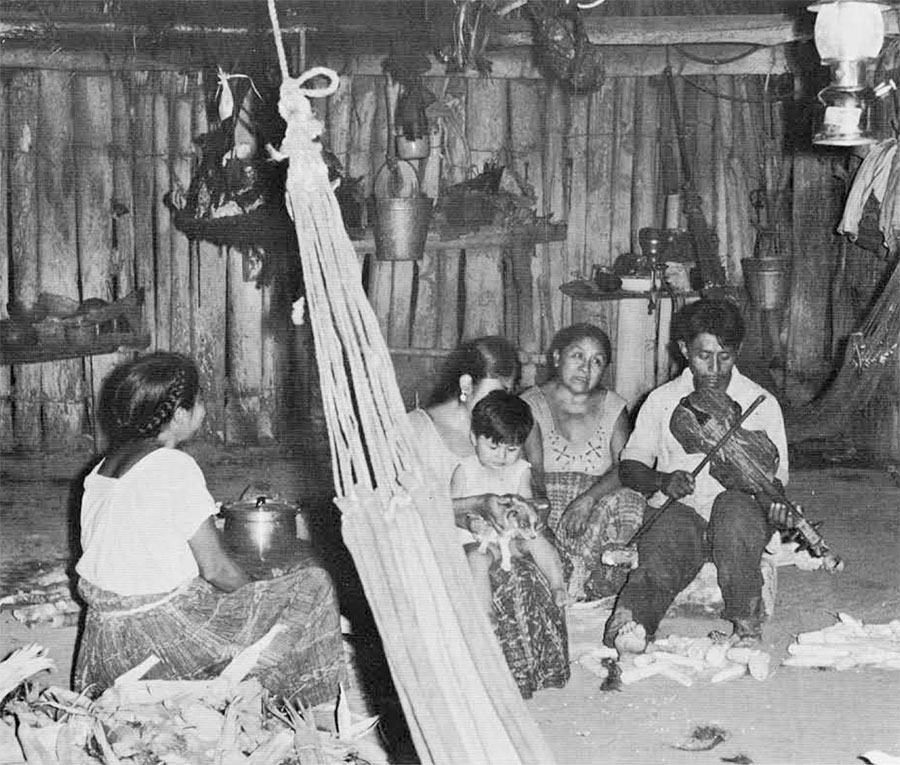

For various reasons it was not possible to start until late May. In addition to the usual supplies, I had brought two hydraulic jacks for raising stelae, kindly lent by the Peabody Museum, and four 5-gallon tubs of latex for making moulds of them, the gift of the British Museum. I signed up Pablo Paredes, one of my guides the year before, whom I knew to be the best worker and most loyal friend one could wish for; his young brother-in-law Hilario; Nemesio, known as “Mecho” for a cook; and Lorenzo, or “Lencho” the mule-driver with his three mules. It was Saturday, May 26th, when the men came round in the early morning and somehow managed to load everything onto the unfortunate beasts; then we set off. The first day took us to Concoma, a settlement of four Kekchi Indian families. To describe the journey, I will quote some extracts from my journal, denoting the days by numbers.

Day 1…the trail, of course, was clear to Concoma, but here and there all the big trees had been blown down in a heap. Stayed in Santiago’s house as before. In the evening lit the Coleman lamp and Santiago took down one of his two homemade violins (one string of nylon, the others of fiber from a coroza palm). Only one tune really, but soft and soothing and nicely played. His youngest nephew aged 1 1/2 danced, although he has never seen anyone dancing. Quite a squash at night with 12 adults and several children sleeping in the house. Santiago’s wife sleeps on the smooth inner surface of bark from a “lanilla” tree, the same that provides kapok for pillows. In the morning, Mecho the cook said a large rat had fallen from the roof into his hammock. Later it ate through his little bag which had tortillas in it.

Day 2: Engaged Santiago and two other Concoma boys to come with us; what I saw of the forest yesterday, and heard last night, convinces me we shall make slow progress…Camped 3 leagues on, ( a league is 4 km., an hour’s journey with mules), by the river bank; this trail already partly cleared.

Day 3: Soon after breakfast a mule standing nearby started violently and there was a shrill scream. We rushed to see what was up; crashing noises; then I saw a tapir with young. Ran to get my camera, but they moved off and plunged into the river with a huge splash. Caught a glimpse of them swimming, like tiny hippos.

Day 4: Sent Jose (Concoma boy) back to Poptun to bring 35 lbs. of food. With 3 extra men to feed we shall not get far unless the going improves soon. Moved on 1 1/2 leagues to Corozal. Boys caught 15 huilin (catfish) using tinamou entrails as bait.

Day 5: Went along with men to do a little amateur machete work. Some big trunks to cut through–sometimes twice, to roll a section out of the way. About 3/4 of trail completely new. I walked back in 15 minutes along a trail that took us 2 1/2 hours to cut. Pablo killed a 2-foot chalpate, said to be nearly as poisonous as fer-delance. In the evening, Jose trotted in with his load, and 2 pineapple to boot.

Day 6: Moved on about 1 1/4 leagues. Had just put up shelter for Mecho and his fire when wham! torrential rain. Noticed mules making purposefully for river bank, then heard heavy splashing (only a pool in a dry river bed here; all the flow is underground). Mules scrambled out and ambled off down river bed for home. I caught one, Lencho the others.

Day 7: Fine morning; dried out things. Found a little grasshopper, clear green, with body 6 millimeters long, its feelers ten times that length…Decided to send a man back to hire another mule and its owner, to bring 100 lbs. maize, plus grinder, lime, etc. Kekchi boys feel weak on diet of flour tortillas. Also sent S.O.S. letter to John Gatling (head of Guatemalan Sun Oil co.) asking him transmit $100 on loan to Poptun. Progress today again discouraging, but I don’t want to give up and lose all the work we have done.

Day 8: Mules are really too naughty; 3 times today they swam across pool in a bid to escape. Poor things, they are savanna-bred and not used to the jungle. Carried a bucket of water at midday to the men. 1 1/2 leagues of rough going, taking care not to spill it. Exhausted. Men returning brought an armadillo and a tinamou (a bird with tender meat, and a surprising lot of it).

Day 9: Talking last night after dark Lencho said that the writing on stones you find at old ruins could not be read. Pable put in: “Oh, but don Juan can” (I wish I could!), “he’s not a mere geologist, but an archgeologist!”…Mecho the cook gets up very early to make tortillas. This morning I heard him calling Pablo; an armadillo had come right up to him, attracted by the light or the smell…Little progress today: many large tamarindo trees, which are worse than zapote to cut, as the wood is stringy.

Day 10: Lencho and I had tremendous battle with the mules, to prevent them landing on the far side of the pool. The three of them swam about for ages while we beat them back with branches. Poor Lencho is worried and depressed by the mules; always taciturn, he has withdrawn more than ever, and will scarcely eat. Sudden sharp rain at 3. Now, after the storm, Lencho announces that the mules have run away! But we left the trail blocked at Corozal. Men say they have still not reached Machaca, as hoped; but we’ll move on tomorrow if the mules are back in time.

Day 11: Mules recaptured. Moved on 2 1/2 leagues; rained all the way. 6 p.m. and exultant whoops announced arrival of Jose with Pedro Ik and his mule. Everyone very cheerful; the sheer numbers–9 of us–made a party spirit.

Day 12: Another day of discouragingly slow progress. Mecho told us of his frightening encounter with the zizimit, a stout furry (and mythical) beast against which a gun is useless: sheer terror always causes the weapon to drop from one’s nerveless fingers. Feet attached backwards, to confuse would-be trackers.

Day 13: Onwards one league, to Machaca. Last year’s champa still standing. Half day off for men; two went fishing, another collected lemons from site of small village that was here in the early 1950’s. All my paper-backs finished, so passed time trying to decipher Chinese hieroglyphics, using Quaker Oats tin as Rosetta Stone. (It has instructions in 6 languages.)

Day 14: Sent Santiago back to Concoma to bring 150 lbs. of maize.

Day 15: Men brought back a sereque, a large relative of the guinea pig, I think. I drew its portrait: could it be the prototype of the Xul animal of Maya hieroglyphics, I wonder?

Day 16: <em jave reacjed “La Cuchara”–so named because the geologists lost a spoon there. They have brought back a peccary.

Day 17: Moved on 2 leagues to La Cuchara.

Day 18: Weather forecasting, Peten-style. Signs that it is going ot rain: a tree falling; wet frog falling upon a person; call of a small black bird “quo-quo-quo”; many little flies; tilted moon; much heat. Signs that it is not going to rain: none.

Day 19: Record progress today: nearly 3 leagues. Mostly through flat corozal where there are fewer big trees, and theres room to take detours. Jose had shot a spider monkey, to capture its baby. Poor thing, it cries pitifully.

Day 20: Miserable monkey cried most of the night. Pablo on his return reports good progress, but is puzzled not to have made contact with River Machaquila.

Day 21: Nobody slept much because of monkey. I turned it loose, and it slowly climbed a tree; hope its relatives will find it. Men returned with disappointing news of still not hitting river. Where can we be? Very gloomy after figuring up the food and money position.

Day 22: Moved on almost 2 leagues. Men came back in the evening after unpleasant day working through flood water up to their knees. I decided to make one last bid, sending Jose and Pedro back to Poptun with a mule for more supplies, and they will airmail a letter to my bank in London.

Day 23: Water ahead receding. A mile has escaped for home; one ought to have a mare along as madrina (godmother) to keep them content. Pablo’s report of meeting the river at last is backed up by a load of fat machaca fish. Leaf-cutting ants, zompopos, have cut three neat round holes in my nylon cape.

Day 24: Moved camp to river bank, 1 1/3 leagues on. River very high and fast. I went on with the men in the afternoon, clambered through appalling pile of trees blocking a small pass, to set eyes on the “dry branch” of the river–now a raging torrent. Returned with 1/2 lb. Quaker Oats tin from last year’s camp, which has helpful variant text for my pastime. Wish I could contribute to the trail-cutting, but I simply put everyone in danger, including myself, when wielding a machete.

Day 25: Small bird sang all morning “Hip, hip, hip, hooray!–pfuit!” Another makes my mouth water with “Haricots verts!” Bad obstructions reported along last stretch of river bank before ruins.

Day 26: Went along to look and (?) help. Long stretches of clean trail through which we passed at exhilarating speed. Then severe obstructions, always in the narrowest defiles between rocky hillside and river. It certainly looks as if the old gods had made a last desperate bid to keep us away, throwing down a chechem tree, full of caustic sap and therefore impossible to cut, with its roots close up to a rockface and its branches in the river. Climbed through with nervous anticipation to see what shape the ruins were in; found a lot of fallen trees–it would have been quite impossible to survey this year–but, wonder of wonders, the plaza where the stelae are is completely clear!

Day 27: The Great Day! Squeezed past the chechem tree roots, and camped between ruins and river. Bushed and cleaned up the main plaza in the afternoon.

The next 2 1/2 weeks were spent in a frantic attempt to take moulds of all the sculpture. Raising the stelae was a nerve-racking task: Stela 10 for example was very large and thick, and when I think of the precarious supports arranged under the little jacks, and the coating of slippery mud on everything, I marvel that no one lost his life, or a limb, under one of these monuments. We also had trouble persuading the latex to harden on the rain-sodden stones. Removable shelters had to be provided for each, and fires kept going. We also built a walled house with shelves for a final drying of the peeled-off moulds.

Pedro and Jose returned with maize, and some letters for me, on the 29th day. Then I paid off the four Kekchi boys, who spent the day amassing birds and fish to smoke, and carry back home. The wretched mules were not accustomed to ramon leaves and bark (a nourishing food), and refused to touch them. Daily they grew thinner, and Lencho more doleful with them. On the 37th day the cook gave notice! We were not conforme, he said, and evidently I was not satisfied with his work. It was true I had bawled him out twice; and he was not a good cook. I couldn’t believe he would actually go; but next morning I saw him packing up his things. However, I buttered him up and he stayed…To Pablo goes much credit for keeping Lencho and Mecho with us, on ever-diminishing rations. Salt then ran out, and at last Lencho announced his intention of leaving next day. I was in despair, since I needed one more day. At that moment we discovered a little cache of salt wrapped in a maize husk, left over from Pedro and Jose’s journey. Stay another day at double pay? Yes. Tinned peaches to celebrate–a taste from another world!

Working frantically that last day, I was driven nearly insane by the call of the Peten dove. Previously I had thought it cried “Quick Quaker Quotes!” but now it was unmistakable “Quick, not so slow!” So, one hears words that express one’s preoccupations; psychologists might develop an aural test analogous to the Rorschach.

On the 42nd day, then, we started for home, happy to have achieved most of our objectives. The river was much higher now, and for long stretches along its banks and across low-lying ground our trail lay beneath one or two feet of water. Two streams we had crossed dry-shod before were full, and we were obliged to hump the cargo across along fallen trees, and swim the mules over. We were now counting the last grains of maize and hunger drove us to daily marches of nine hours. The return journey to Poptun thus took three days only; we had a surplus of provisions amounting to about 10 cents worth of peppercorns, and four ounces of baking powder.