The second river of Paradise is said to have run through the Biblical land of Kush or Nubia. Modern Nubia actually consists of 22,000 square miles of austere sandstone, granite, and desert. Though no boundaries exist where Egypt ends and Nubia begins, the latter extends from Aswan to Khartum. A land of measureless silence punctuated only by the flow of the Nile, Nubia held a hypnotic fascination for Amelia Ann Blandford Edwards.

This Victorian lady, born in London in 1831, became a successful novelist, publishing no less than eight by 1880. In the winter of 1873-74 she visited Egypt. This changed the entire course of her life. From that time on she became a student of Egyptology, applying herself to the study of hieroglyphic writing and Egyptian literature. She believed that the great Egyptian antiquities would be destroyed if proper scientific investigation were not instituted. To this end she did two things. She devoted herself to publicising the need for archaeological research in Egypt by means of writing and lecturing. Her lecture tour brought her to the United States in 1889-90 and resulted in a publication Pharaohs, Fellahs and Explorers in 1891. She was largely responsible for the founding of the Egypt Exploration Fund in 1882.

This society began systematic, codified archaeology in Egypt under Edouard Naville and W. Flinders-Petrie. Not only did the Fund conduct excavations but it published its findings and engaged in research basic to the development of Egyptology. The Fund was financed for the most part by institutional subscribers who shared, in proportion of subscription, the season’s finds. The University Museum built its initial Egyptian collection as a member of the Fund. Hundreds of objects in the Museum are here because of the foresight and interest of Amelia Edwards.

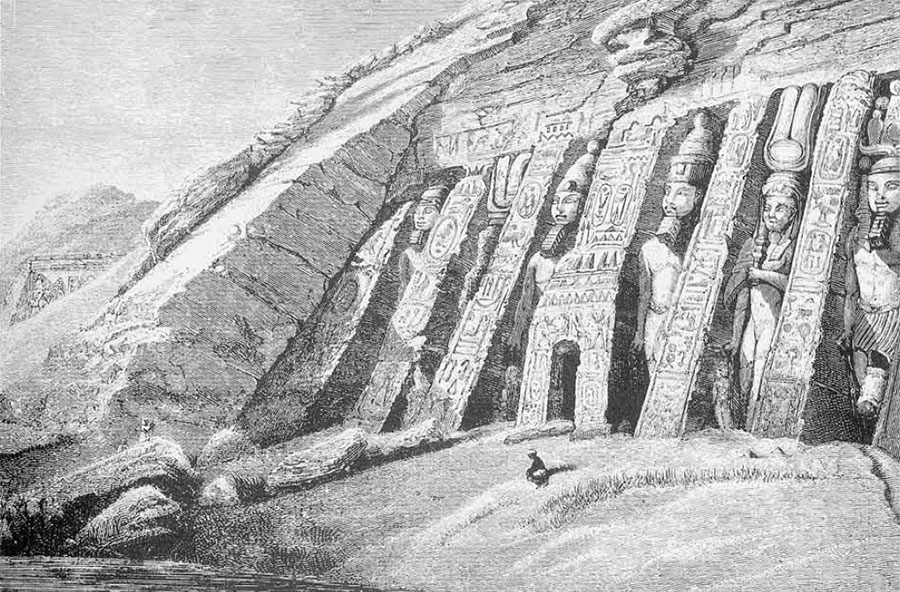

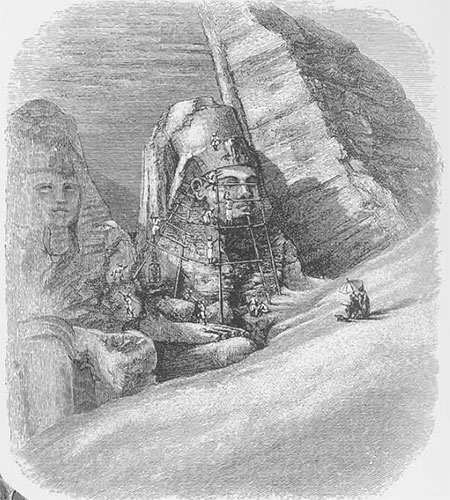

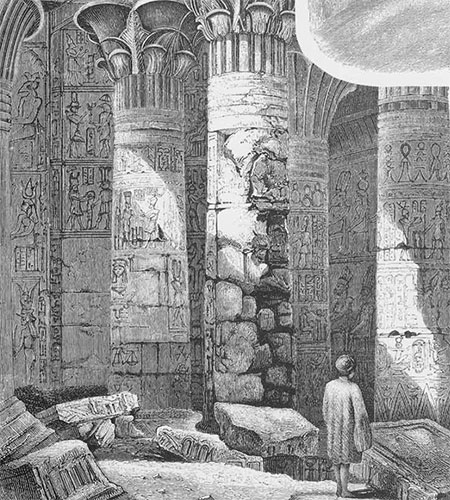

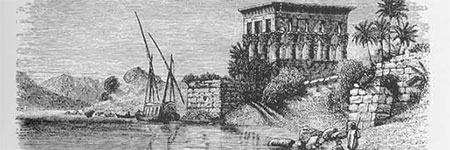

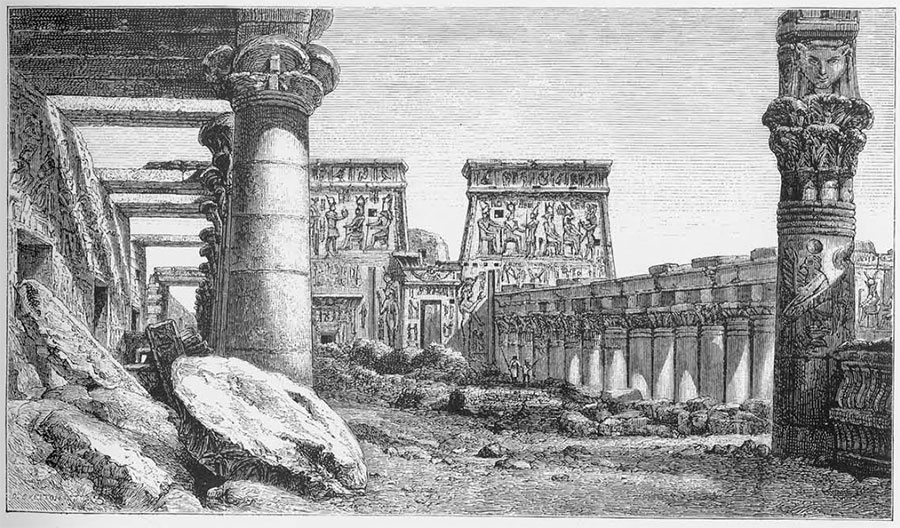

In 1877, three years after her prolonged stay in Egypt, Miss Edwards published a volume, partly a guide, partly a diary account of her discovery of the Monuments of Egypt. 1000 Miles Up the Nile went into three editions. Its prose is enthusiastic and readable but most charming are the upwards of seventy illustrations which were done by Miss Edwards, a quite competent watercolorist. For publication they were “engraved on wood by G. Pearson after finished drawings executed on the spot by the author.”

No writer was more sincere in preserving the Pharaonic heritage of Ancient Egypt. No artist lavished so much care on careful notation of the Ruins as she in her drawings. Today Miss Edwards would be the first to advance the great UNESCO salvage project to save the Monuments of Nubia before the new High Aswan Dam covers them. A selection of her watercolors translated by Mr. Pearson into black and white shows these monuments as she knew them. Short passages from her text have been chosen to describe them. Together, they may restate her glimpse of ageless Nubia.