Southern Etruria lies in the volcanic hills north and west of the Tiber. This region was occupied by the Bronze Age people, later by the Etruscans and the Faliscans of the Iron Age, and still later, very extensively by the Romans. During the Middle Ages the area was little used and became overgrown with vegetation. This helped preserve the remains of human habitation sites abandoned in late Roman times when people began to withdraw into villages.

In the years after the Second World War these remains of ancient sites were threatened with destruction. One of the threats was the result of the land reforms which created the communal farm of the Ente Maremma. This farm has profoundly affected the land lying in modern Tuscany and in Lazio, north of Rome. Land, unused for hundreds of years, has been opened up for agriculture: it has been cleared and houses have been built. The most drastic loss, archaeologically speaking, has resulted from the communal ownership of very heavy agricultural equipment. The deep plough, which digs a furrow to the depth of one meter, churns straight through and destroys anything lying to that depth below the surface.

Another threat to the land is the vast amount of new housing spreading out from Rome in all directions. To the north, into the Etruscan country, whole new communities have grown up along the Via Cassia and the Tiber valley is filling up with highways and houses. Farther north, by the Lakes, resort areas are being developed.

The threatened disappearance of ancient remains convinced John Ward-Perkins, Director of the British School at Rome, in 1954, of the need for starting a South Etruria Survey. He hoped to get out into the land ahead of the bulldozers and the deep plough, and to record as much as possible. The aim of the Survey has been, briefly, to record ancient and mediaeval sites, roads, and bridges, and to note other surface features.

The area of Southern Etruria which has been under survey is covered with tufa formed from volcano fall-out or mud-flows from the main volcanic centers of Lakes Bracciano, Vico, and Bolsena. Tufa has certain properties which make it very important and interesting to our study: it is a loose rock, lying in layers and varying greatly between the layers in the degree of its compactness; the living rock is easily broken or cut, but on exposure to the air, the more compact varieties set hard as they dry out. Thus, tufa can be used for building blocks and for good, hard, natural road surfaces; also, because it needs no shoring, it makes an ideal medium out of which to cut chamber tombs and underground waterways. Another important feature is that when the surface of the rock is broken up it continues to provide good agricultural land because its components contain all the elements necessary to support plant life. Additionally, while areas of harder rocks such as limestone retain evidence of human activity only in such definite aspects as quarrying so that when buildings disappear there is no sign of their ever having been there, tufa, while soft and very easily worked, once it has been affected by man retains the evidence of his presence in such features as flattened hilltops which had been the sites of houses, road cuttings and levelings, even a much used track.

The area of Southern Etruria which has been under survey is covered with tufa formed from volcano fall-out or mud-flows from the main volcanic centers of Lakes Bracciano, Vico, and Bolsena. Tufa has certain properties which make it very important and interesting to our study: it is a loose rock, lying in layers and varying greatly between the layers in the degree of its compactness; the living rock is easily broken or cut, but on exposure to the air, the more compact varieties set hard as they dry out. Thus, tufa can be used for building blocks and for good, hard, natural road surfaces; also, because it needs no shoring, it makes an ideal medium out of which to cut chamber tombs and underground waterways. Another important feature is that when the surface of the rock is broken up it continues to provide good agricultural land because its components contain all the elements necessary to support plant life. Additionally, while areas of harder rocks such as limestone retain evidence of human activity only in such definite aspects as quarrying so that when buildings disappear there is no sign of their ever having been there, tufa, while soft and very easily worked, once it has been affected by man retains the evidence of his presence in such features as flattened hilltops which had been the sites of houses, road cuttings and levelings, even a much used track.

The work of the South Etruria Survey has been steadily pursued since 1954 by John Ward-Perkins himself, by certain Rome Scholars of the British School, and by many volunteers, some complete amateurs. Areas covered have been published regularly in the Papers of the British School at Rome, the culminating publication being that of the Ager Veientanus work in 1969.

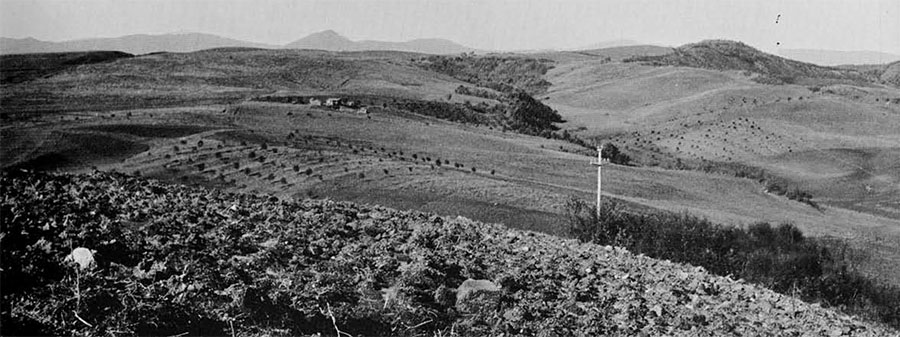

As part of the Survey, I worked during the winter of 1966-67 surveying an area between the Via Cassia, the Via Clodia-Braccianese, and Lago di Bracciano. The area covers some seventy square kilometers and comprises the southern crater edges and slopes of Lago di Bracciano and the subsidiary craters at Baccano and Martignano. The ragged edges of the craters give place farther south to a gently rolling plateau which is gradually being cut into by streams running into the Tiber and the sea. Today the land, except for the steepest slopes, is used for the growing of wheat and vegetables.

Each day I took my car and drove it down unbelievable dirt roads, through mud, streams, and fields into the countryside. Walking out from the spot where I had finished the previous day, I carried camera, map, trowel, pencils, compass, plastic bags, and lunch, and looked for new sites. In fact, certain ancient features are easily spotted; Roman wall foundations, made from excellent cement, often leave substantial remains. One Roman building in a particularly isolated place still stands, in part, to a height of three stories and another to two stories. Changes in the color of the ploughed land may indicate a site and a pale patch in a field is always worth investigating, as it may be crumbled cement wall foundations with pottery sherds and other evidence of occupation. It is necessary, also, to keep a sharp lookout for anomalies in the land, such as a cutting where there is no stream bed. Patches of brambles may indicate a pile of stones which the farmer has thrown into the corner of a field, or they may cover a Roman foundation, a Roman cistern entrance, an Etruscan tomb, or the airshaft to an Etruscan underground waterway or cuniculus.

One good source of information is the local people, shepherds and farmers. They never seem to mind people walking over their land and will always talk to a stranger, particularly one who appears to be a madman, walking round in circles, staring at the ground, and picking things up. They usually know where the sherds are and are invariably friendly and helpful. Widenings in roads and new gas station excavations can be fruitful sources of finds, as often there will be a cutting through the old roadbed or even through one of the tombs which lay along the roadside.

Once a site is located a record is made. It should be noted here that the sites found in this area, in almost all instances, are single buildings though they vary from vast villa complexes to herdsmen’s huts. The spot is marked on the map and a six-figure number, based on the grid coordinates, assigned to it. Representative sherds as well as marble samples, mosaic tesserae and glass, if present, are taken from the site, and any building materials are noted. If any part of a building is encountered, such as foundations or walls, these are sketched and a ground plan made. The finds are later washed, numbered, recorded, and filed. Certain sites of special interest are reported to the Italian Government, which has the power to prevent destruction or use of the immediate area. A particularly prosperous villa, a site occupied through several periods, or a site with a specific use, such as a roadside way-station, might be worth saving and investigating.

The surveyor is also on the lookout for roads.

The Roman highways often left clear, deep cutting, near to the modem road in many places, and along certain stretches the well-made paving with its curbstones still remains in situ. The large paving blocks, made from a basaltic rock found locally, look rather like kettledrums laid on the ground flat side up. Sometimes it is possible to see these blocks in use as part of a modern wall or, disturbed by the plough, simply rolled to the side of a field. Once spotted, the blocks suggest that there had been a Roman road near here. We have found so many of these paved roads that we have concluded that the Romans, in this area at least, ran private paved roads out to their villas. Etruscan roads are more elusive. There is no evidence of their roads ever having been paved, and the traffic through the countryside was probably not heavy enough to wear deep ruts. Round such big cities as Veii, Caere, and Tarquinia, the roads running into the city are quite clearly defined as cuttings, but farther into the hinterland they are not so visible.

Basically the results of the surveys have been presented in maps of sites and roads, designed to show the occupation of the land and the communications used in different periods. Ideally, occupation patterns are plotted on the basis of datable pottery but in this survey the valid dating of the pottery found presented the surveyors with an immediate problem. One type of pottery, the Black Glazed ware, is believed to have been in use for three hundred years, which makes it far too vague for exact dating purposes. Other types such as the Arretine Terra Sigillata and its imitations have been extensively studied in terms of decoration, but when one is faced with small sherds without any decoration, an identification based on fabric and glaze is needed. Other types of pottery found regularly, such as the Red Polished wares known vaguely as Late Wares, have had no thorough publication. Yet other types had never even been recognized, let alone identified. Two Etruscan wares, identified as Etruscan by their context in the excavations near the northwest gate at Veii, have been recognized. One is a coarse ware featuring a beaker with almond-shaped rim and having an interior slip; the other is a fine cream ware with a soft fabric, often undecorated but occasionally having a painted decoration of simple lines on the outside. These new pottery types were originally given names off the cuff but they have now been described and given a formal name in the 1969 Ager Veientanus publication. This has not only been essential to the proper analysis and publication of the Survey results but also its value to students of pottery in Italy cannot be overestimated, as some of the less spectacular pottery, previously overlooked, can now be useful archaeologically.

Thus, recognition and acceptance of certain unknown or unwanted pottery types have been an important result of the Survey work. In spite of the difficulties inherent in the pottery dating, the results can be used to show the changes in occupation of the land in ancient and mediaeval times. Information gathered into pottery distribution maps gives consistent patterns throughout the area, even illustrating geographical and historical variations. To illustrate the use of the region, I use my own results from the area south of Lago di Bracciano.

The earliest occupation of which we have any evidence is during the Bronze Age, probably datable in this context to about 1300-1000 B.C. It should be noted that there is an interesting, consistent lack of any Neolithic remains throughout the hills covered by the Survey in general. Bronze Age remains have been found elsewhere, for the most part along river valleys, but the site in this area lies on the ridge south of the lake.

The next period represented in the occupation of the area is Classic Etruscan, that of the sixth through the fourth centuries B.C. The protoEtruscan Villanovans were well established in the city centers of Veii and Caere but are not represented in this immediate area. The area is thought to have been under the control of the Caerites, since the River Arrone has been taken as a convenient dividing line between the territories of Veii and Caere. This puts the Survey area into the furthest corner of the Caerite territory and may be the reason for its late use.

1. Etruscan sites and tracks

2. Sites in which Black glazed pottery was found

3. Sites with Terra Sigillata

4. Sites occupied during the firs and second centuries A.D.

Evidence for the occupation of Etruscan sites is based on the presence of one or more types of pottery. Bucchero, the well-known grey to black fabric with the burnished finish, appears in small quantities. It was made locally during the sixth and fifth centuries B.C. The fine cream ware of the type found at Casale Piano Roseto and recognized also by its twin flanged bowls is another fine Etruscan product. Coarser wares are represented by the almond rims, with or without interior slip. A characteristic Etruscan feature is the flaring horizontal handle which is so distinct and so indestructible.

Etruscan occupation of the area can be recognized as either ‘hilltop’ or ‘roadside’ in setting. The site which lies on the highest point of the southern crater edge of Lago di Bracciano and which has a magnificent view could well have been a lookout post. Other sites close to it on the high land are placed alongside what must have been a track leading to the highest place. The very ancient track from Anguillara to Caere ran through this area and there are sites near it. The area was still forested in Etruscan times and such settlements as were made were probably put close to the tracks for this reason.

For evidence of occupation in the years immediately after Veii fell to the Romans in 392 B.C., we turn to the use of Black Glaze pottery. This is a fine buff ware with a fairly good black glaze and carrying a stamped decoration. Finds of this type of ware from Cosa and the Roman Forum have been well published but it has been difficult to tie the Survey finds in with the results from those areas. Local production and a cultural time lag confuse any attempt at a precise conclusion. It is believed that this Black Glaze pottery was in use from about 300 B.C. but that the particular type found in the Survey area is mainly one produced about the end of the second century B.C. Production of the standard ware continued down to the end of the first century B.C. when that of Terra Sigillata got under way. Its presence suggests a Roman Republican occupation, no more. Nor, unfortunately, did we find any other pottery of this period which would help produce more exact results. However, the distribution of Black Glaze pottery within the area does have its own distinct pattern which reflects the gradual opening up of the land as the Romans moved in.

Settlements lie close to the old track to Anguillara and on the ridge tops. This suggests that the old tracks were still in use and that the forest was gradually being cleared by the roadside. A new feature is the new road which must, therefore, have been built by this time since settlements appear along it north of the Anguillara track. This is the Via Clodia which originally ran from Rome out into the country where the Etruscan towns at modern Blera, Barbarano Romano, San Giovenale, and Nerchia lay.

With the advent of the use of Arretine Terra Sigillata we come into the Augustan period and the early Empire. This ware was made in Arezzo from 30 B.C. to the end of the first century A.D., but it continued to be made in other towns in Italy into the second century A.D. There is no local chronology for this ware but it is accepted as having been in use locally from about 30 B.C. to about A.D. 150. Its distribution shows continued occupation of roadside and hilltop sites but with a new opening up of the flatter agricultural land to the east. The hilltop sites show up as very prosperous places, with much marble, glass, and examples of finer pottery, suggesting that they were villas of the wealthy. One of the roadside sites appears to have been a way-station, lying as it does right on the roadside; it was occupied throughout the whole Roman period. Sites in the flatter area were evidently not so prosperous as those on the hills but still they appear to have been substantial farmhouses.

Two types of pottery apeared in usage during the decade A.D. 60-70, Beaker ware and the Red Polished ware. The former has a fine, thin, hard fabric with mica inclusions, which was fired to a medium or chocolate brown. Delicate strap handles have two or three vertical ridges and usually there is rouletting in a wide band round the belly of the pot. This Beaker ware imitates the silver vessels of the day. Red Polished ware, known otherwise as Terra Sigillata Chiara and Late Wares, has a hard, brick-red, not well levigated fabric; it breaks roughly, showing characteristic lines parallel to the exterior. Well fired, it has a hard polished exterior. Studies made in Southern Etruria by J. W. Hayes have identified this pottery as having been in use from the last half of the first century A.D. through to the seventh century. Its earliest production was in North Africa and the ware was quite thin; later it became heavier but it appears to have continued in use in humbler homes as a substitute for the glass or metal tableware used by the rich. A coarser, unpolished version of the same ware is also found, usually in the same context, which must have supplied an even humbler need.

Within this Survey area the types of Red Polished pottery found are those from the first through the third centuries A.D. The occupation of the area shows continued use of the villa sites on the hilltops and of the huge villa complex at Mura di San Stefano. Private roads ran out from the Via Clodia to the villas—in the case of the Mura di San Stefano a distance of two kilometers straight across the country. The flatter land in the east was by this time opened up completely for use, but a few of the sites there were of an exceedingly simple nature, the only finds being roof tiles and coarse pottery. These may well have been herdsmen’s cottages at a time when much of the land in Central Italy was being used for ranching. During the first and second centuries A.D. the Via Clodia continued to be used as a main road. If the track to Anguillara was still used by farmers, it was apparently not paved.

By the third century, however, the more exposed and agriculturally marginal land was abandoned, only the big villas remaining in use into the fourth century. This dramatically reflects the economic depression of the third century and the devastating plague of the middle of that century.

Threats of roving marauders and the reduction of the population sent the survivors into fortifiable villages and away from the roads and the open farmlands. During the Middle Ages, from the tenth century A.D. onward, the people lived in villages which, in many cases, were on the sites of Etruscan villages, and went out to work in nearby fields by day. There is no evidence of use of the Survey area in Mediaeval times except a chapel built into the villa at Mura di San Stefano. The countryside reverted to the scrub macchia and in some places even the paved Roman roads were lost.

In summarizing the patterns of occupation in this area we can say that at first hilltops were used, as were fortifiable villages such as Anguillara. Tracks connected the villages, towns, and lookout posts, and some farms were cut out of the forest in Etruscan times. By the early Roman occupation a new highway had been established and farms were put fairly near to the roads. During the Roman Empire down to the end of the second century A.D., villas were maintained on the high land, and the flatter area suitable for farming was gradually opened up, so that it seems certain the whole must have been cleared of forest during this period except for some trees which remained on the hill slopes down to the sixteenth century. Life was secure and prosperous. From the third century on, economic disaster combined with the plague, and later followed by attacking marauders, drove a reduced population into safer places. They left the open fields and roadside places. It was not until the advent of the modern era that it was safe again to come out into the open countryside; the motor vehicle has helped this trend and today’s pattern of occupation is very close to the Roman one. In fact, new farmhouses of the Ente Maremma are found with startling regularity on the sites of Roman farmhouses.

Work continues in Southern Etruria whenever an interested scholar or willing volunteer turns up. If possible it would be ideal to excavate the Etruscan hilltop site and the Roman way-station because they would give much valuable information. There is also a need now for further surveying to be done in an entirely new region, different both historically and geologically. It is hoped that it will be possible to start work next year on an area south of Rome. That will mean new problems but eventually new information.