“In the beginning God created Black as well as White Men…God having created these two sorts of Men offered two sorts of Gifts, viz. Gold and Knowledge or Arts of Reading and Writing, giving the Blacks the first Election, who chose Gold, and left the Knowledge of Letters to the White.” This report of the creation of man was related by the Netherlandish traveller William Bosman in his extensive letters describing the Gold Coast in 1698. He speaks more specifically about the chosen gold in another letter: “They are possessed of vast treasures of Gold besides what their own Mines supply them with by plunder or their own commerce…The Gold…is very pure, except only that ’tis too much mixed with Fetiches which are a sort of artificial Gold composed of several Ingredients…These Fetiches they cast (in Moulds made of a sort of black and very heavy Earth) into what form they please…There are also Fetiches cast of unalloyed Mountain Gold; which very seldom come into our hands, because they keep them to adorn themselves…”

The Museum is very fortunate to have on loan and therefore temporarily “in our hands” just such an ornament, a so-called soul-washer badge–a disc seventeen centimeters in diameter of the pure mountain gold. This cire perdue casting is a triumph of hollow casting. It also embodied a triumph of ceremonial usage. Called Akerakomu, the badge was carried by the soul-bearer around his neck on a white cord made of the fibers of pineapple leaves. Only the soul-bearer, or Okrofo could be the porter of this badge whose purpose was to ward off evil from the soul of the king. This office was usually held by a member of the royal family. The soul-bearer always preceded the king in procession and sat before him on ceremonial and official occasions. The position carried with it special privileges on feast days and annual festivals.

The soul-washer disc in the Museum is of particular interest as an example of acculturation. For over one hundred years European traders had introduced merchandise from the continent. Diplomatic and official representatives imported their own stylish paraphernalia for use during their tenure. How natural for the already sophisticated Ashanti kings to absorb or even adopt the European motifs of the objects representative of their particular ceremonial paraphernalia. Such is the case with the decoration on the disc here illustrated. Regular classical palmettes are raised in the orderly geometric band of the disc. One is immediately reminded of the particular renaissance of this classical motif in the French Empire style. On closer examination, the decorative scheme of the raised palmettes seems to have been translated directly from an ormulu prototype on furniture or a decorative garniture. Thus we can safely place the piece in the first half of the nineteenth century.

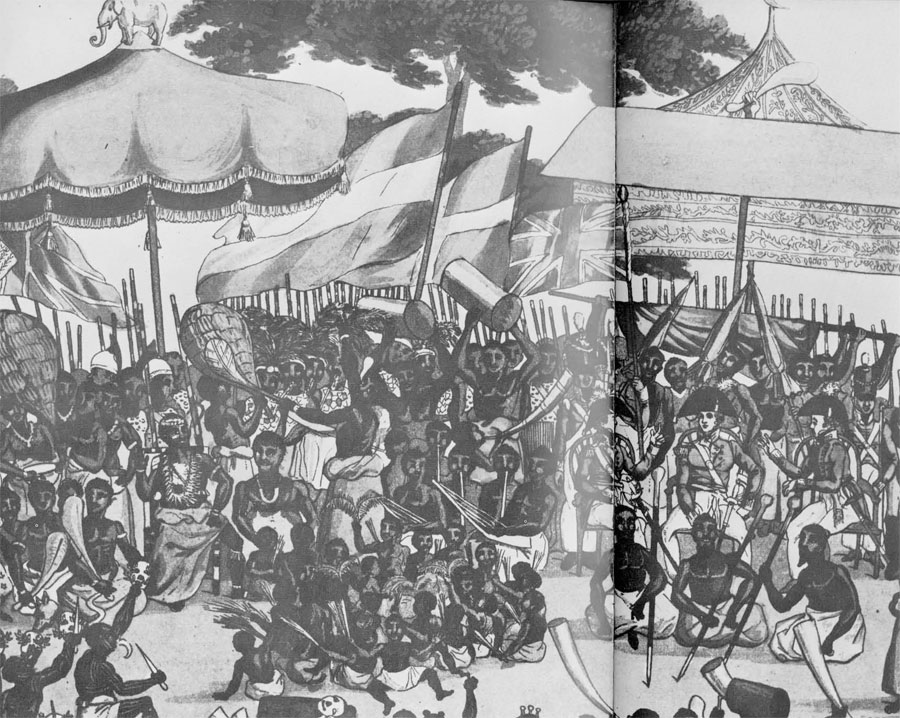

This soul-washer badge is only a small aspect of the great treasure store of the Kingdom of Ashanti. Nothing exceeds the description of the sumptuous reception given by King Sai Touton Ouaimma for an English ambassador in 1817. The king, his vassals, and his captains were surrounded by their servants. The rays of the sun reflected with brilliance an almost insupportable heat from the massive gold ornaments. Umbrellas capable of sheltering thirty people were surrounded by gold animals. All wore massive necklaces. The king’s messengers-of-state wore on their chest great golden plaques. The king himself was adorned with necklaces and bracelets and his chest was covered entirely with an ornament resembling a golden rose. In front of him sat his soul-bearer wearing just such a plaque as this.