Museum Object Number: 59-24-1

The Etruscans are still a mysterious people to us because at the present state of our knowledge we cannot answer the question of their origin. This, our misfortune, is partially due to the fact that twelve cemeteries are all that remain of the great loose confederacy of twelve cities which thrived in Central Italy in the seventh and sixth centuries B.C. The result is that we know more about the Etruscans’ beliefs concerning the next world than we do about how they lived and behaved in this world.

Last October a sculptural fragment from an Etruscan cemetery was purchased for the Mediterranean Section of the University Museum. It had reposed for some time prior to that in other collections and its original provenience in Italy is undisclosed. For this reason conclusions about it must be based on the inner evidence of style, technique, and material.

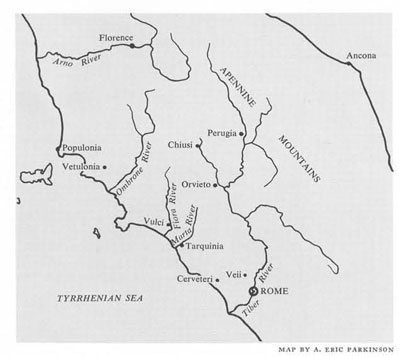

The idea that lions, lionesses, leopards, sometimes winged, sometimes not, were suitable guardians of sepulchres because they had protective powers was an ancient Oriental one which spread to Egypt, Anatolia, even Mycenae, during the Bronze Age and was brought to Etruria from the East. As inspirers of dread, then, they were, for instance, placed at each side of the entrances of chamber tombs which were cut into hills (as Veii and Cerveteri), or painted on the walls inside the door. When no hills were available and tumuli were built, they were sometimes put on the peak or ranged round the top of the low girdling walls (as at Chiusi and Vulci). On temple-like sarcophagi deposited inside the tomb chambers (as at Chiusi) they might be found on the lids, either adorning the ridges of each facade or facing outward from each corner.

The Philadelphia lion must have served one of these purposes–but it is to be observed that he is most likely a standing figure. His size would preclude his ever having been merely part of a sarcophagus–as he is slightly over two feet high although broken across the forelegs. He is abraded on his right side and broken behind the shoulders far enough back to reveal the attachment of raised wings, but no evidence is left for the position of the back legs and tail or for the presence of a plinth.

The style of the head is intriguing because the deep vertical cleavage down the forehead, the tendon areas at the back of the foreleg, and the ears half closed down from above although drawn back against the head, all recall the archaic Greek lions in the Corfu Museum dated between 600 and 530 B.C. The thin standing ridge which indicates the mane and the ridgelike ruff behind the jaw resemble those on the seated lion done in relief profile upon the bronze tripod said to be from Perugia, now in the James Loeb Collection in Munich, and dated to the third quarter of the sixth century. The separate jaw- and brow-ruffs, and the ears, are paralleled on a small bronze lion in the round from the collections of the Munich Museum dated to the second half of the sixth.

The Philadelphia lion combines these characteristics, adds the wings of the Etruscan tomb guardian, and might on style alone be dated toward the last quarter of the sixth century B.C.

The technique of the sculptor in this instance is somewhat difficult to analyze, as the surface has been carefully smoothed afterwards with a rubbing tool. But along the wing’s curve half-obscured parallel lines show the use of the claw-chisel. Also in the back of the mouth, where later smoothing did not seem necessary, at least five claws can be distinguished. The definite delineation along the ridges and the soft curves elevating the wider planes show a very careful hand with the smoother. The nature of the stone, which contains hard granular bits, was responsible for the partially roughened final surface, because these bits, as in all tufas, which are soft and sandy in composition, have a tendency to rub away or fall out. The piece in general shows excellent workmanship, and nothing observable concerning the technical means used is inconsistent with a date in the late sixth century.

The evidence of the material from which it was made is of some aid in determining its geographical source. Tufa in general was preferred for sculpture in the area from Orvieto on south. North of that sculptured pieces are more likely to be in sandstone and limestone. The pale gray color and fineness of this tufa locate it in central Etruria where such sculptures are well known from Tarquinia, Vulci, and Orvieto. When lists of finds of sculpture in the round from these sites are consulted, it is found that the greatest number of gray tufa lions in captivity comes from Vulci. There are others from Vulci in Berlin, Florence, and The Vatican. The example in the University Museum, then, appears to have numerous and handsome relatives if not a formal pedigree.

Photographed by: Reuben Goldberg