The remarkable Chinese maps published by Mrs. Bulling in the previous article indicate that in cartography, as in many other things, ancient China was far ahead of contemporary cultures in the western world. This article is an attempt to document that statement by giving a brief survey of the development of cartography in the west down to the time of the Greek geographer Strabo.

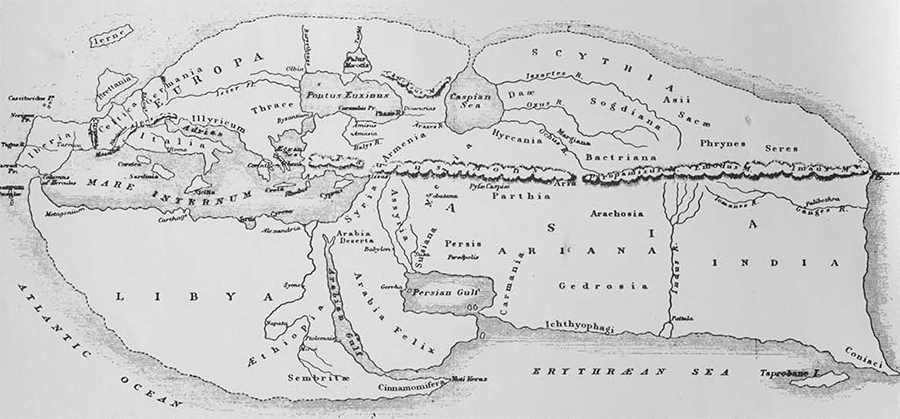

Born in about 63 B.C. Strabo had written major works on history and geography by the time of his death in A.D. 21. His most famous work is a Geography, in seventeen books, giving a description of the known world, from Britain and Gaul in the west to India in the east, giving some information on Europe and the Balkans in the north and extending as far south as Ethiopia. The knowledge of the world possessed by Strabo represents, in some aspects, an improvement over the system of his great predecessor Eratosthenes (ca 275-194 B.C.), a scholar for whom Strabo had little respect.

The Geography of Strabo gives us our best evidence of the actual geographical knowledge of the pre-Christian world as well as being our major source of information for the growth of this knowledge from the time of Homer onward. Strabo gives a critical evaluation of the work of his predecessors and even provides a brief description of some of the technical problems in the drawing of maps. Strabo places great emphasis upon travel and the importance of first-hand experience and remarks that:

“You could not find another person among the writers on Geography who has travelled over much more of the distances just mentioned than I.”

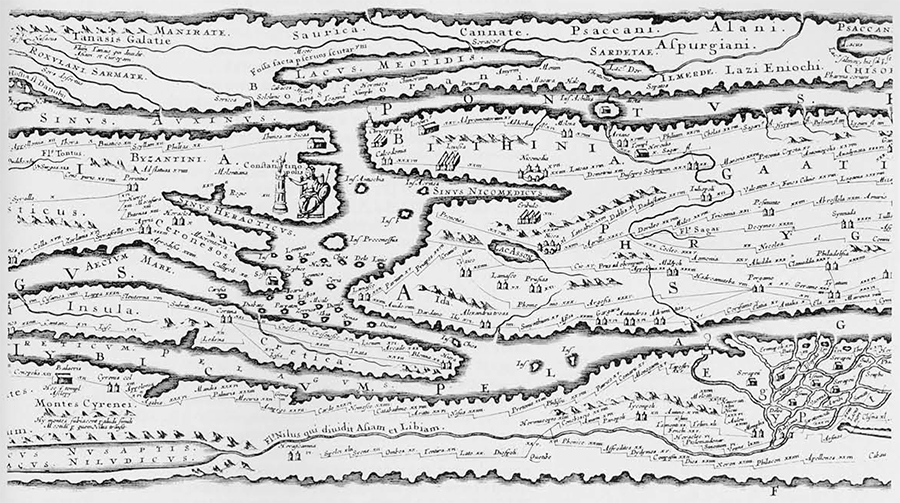

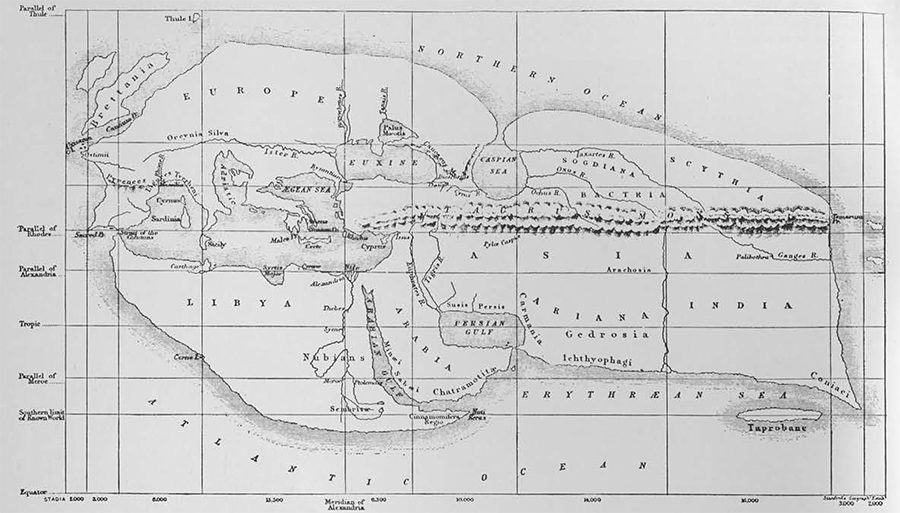

However, there is reason to doubt that Strabo’s travels took him much further than Rome and Alexandria, parts of Asia Minor and Egypt. His description of Greece is really more mythology than geography. Yet the world known to Strabo, depicted here in a modern reconstruction based upon the information given by him, was accurate in its main features and presents a view of the Mediterranean and the Middle East at least recognizable in its general outline.

There are many references to maps in the surviving works of Greek and Roman authors, but few actual examples have survived to the present day. Most of our examples come from the time of the Roman Empire. Much of our knowledge of the topography of ancient Rome is based upon a plan of the entire city, the Forma Urbis, affixed to the walls of a building in the Imperial Fora by order of the emperor Septimius Severus about A.D. 200. Fragments of this stone map came to light in 1562 and, though some of these panels were subsequently lost again, they were first copied in a manuscript now in the Vatican Library. Even more extraordinary is the story of the most detailed map to survive from the ancient world, the Peutinger Table (Tabula Peutingeriana) a third or fourth century road map known only from a copy made by a monk of Colmar in the mid thirteenth century and acquired by the German humanist Konrad Peutinger in the sixteenth century. This map is in the form of a long narrow strip, (a foot high and 21 feet long), in twelve sections, giving a greatly elongated view of the Roman world from Britain to the mouth of the Ganges (most of Britain and all of Spain are missing in our surviving copy). This is a road map designed for travellers and, like modern guide books, it gives information on hotels, restaurants and accommodations available along the road.

There is actually much information available for the Roman road system and for what we can best call itineraries (in Latin itineraria adnotata). Such works go back to a map of the Roman Empire set up in Rome by Agrippa during the reign of Augustus. Nothing of this map has survived, but we do have a later version of it, the so-called Antonine Itinerary (Itinerarium Provinciarum Antonini Augusti) compiled in A.D. 217, during the reign of Caracalla, and giving military routes with way-stops and the distances between them. All the evidence for these ancient itineraries was compiled in the Itineraria Romano, published by the German scholar, Konrad Miller in 1916.

All of the surviving maps described above are much later than the Chinese maps discussed by Mrs. Bulling. The question of ancient Greek maps, earlier than the Chinese ones, is a complex one for we have no surviving examples. There are many references to such maps by Greek authors, and a passage in the Clouds, a comedy by Aristophanes, refers to a map of the world being brought on stage. Several of these references indicate that the concept of a map of the world, with lands drawn to scale, was unfamiliar to the inhabitants of fifth century Greece. As always, Herodotus has the best story. It concerns the Ionian Revolt (499-494 B.C.) when the Greeks living on the Aegean coast of Turkey tried to establish their independence from the Persian Empire.

Aristagoras of Miletus, the leader of the revolt, went to Greece to persuade Sparta, the leading military power of the Greek world, to join the revolt and send an army to fight against Persia. Aristagoras brought with him a map of the world engraved on a bronze tablet, the work of the geographer Hecataeus and showing “the whole circuit of the earth, the seas and the rivers.” Aristagoras pointed out to Cleomenes, the king of Sparta, the lands of the Persian Empire:

” ‘Look,’ he continued, pointing to the tablet, ‘next to the Ionians here are the Lydians—theirs is a fine country, rich in money. Then come the Phrygians, farther east, richest in cattle and crops of all the nations we know. And here, adjoining them are the Cappadocians—Syrians we Greeks call them; and next to them the Cilicians, with their territory extending to the coast—see, here’s the island of Cyprus—who pay annual tribute to the Persian king of five hundred talents. Now the Armenians—they, too, have cattle in abundance; and next to them, here, the Matieni. Again, farther east, lies Cissia, you can see the Choaspes marked, with Susa on its banks, where the Great King lives, and keeps his treasure. Why, if you take Susa, you need not hesitate to compete with God himself for riches.”

Cleomenes was very much interested, for he was a greedy man, but, he asked, how long would it take to go from Ephesus to Susa following the route of the great Persian Royal Road. Here, says Herodotus, Aristagoras made his big mistake for he told the truth. When Cleomenes heard that the journey would take no less than three months he ordered Aristagoras to leave Sparta before sunset. Cleomenes was not about to commit Spartan troops to such an enterprise, now, but before the relative distances on the bronze tablet of Hecataeus had meant nothing to him.

A story included in the True Histories (Variae Historiae) of Aelian, written in the third century A.D. concerns the philosopher Socrates and his pupil Alcibiades. After hearing him boast of his wealth and the extent of his land holdings Socrates took Alcibiades to a spot in Athens where was a plaque containing the circuit of the earth. When Alcibiades had finally located Attica Socrates then asked him to find his property, but, of course, he could not do so:

” ‘These then,’ said he, ‘make you boast, though they are not even a part of the earth.’ ”

A nice example of the limitations of a small world map; unfortunately we have no direct evidence for the actual appearance of any of these early Greek maps. The evidence we do have suggests a rather primitive form of cartography with land, ocean and rivers shown only by the barest outline.

For actual maps from an early period we must turn to the Ancient Near East where archaeologists have uncovered several interesting maps inscribed on clay tablets. One of the earliest comes from the Old Akkadian level at Nuzi, in northern Iraq, from the time when the site was known as Gasur. Inscribed on a clay tablet during the latter part of the third millennium B.C. the map shows settlements, streams and hills or mountains, the latter indicated by a scale-like pattern.

Unfortunately we do not know exactly what area is represented on this map, so little can be made of this document.

Out of the great current interest in Ebla, now known to be the site of Tell Mardikh, where Italian archaeologists have uncovered monumental buildings and an archive of over 17,000 tablets, has come a revival of the suggestion first made by Theophile J. Meek in 1935 that the Nuzi map mentions the city of Ebla. In the lower left corner of the map the scribe has circled the Sumerian signs reading MAS-GAN BAD EB-LA. This, Meek suggested, might be a reference to the city of Ebla, known as an important site in the Sargonid or Old Akkadian period (24002200 B.C.).

If this is a reference to Ebla it is odd that the name is written without the sign KI after it, the Sumerian determinative indicating the name of a city. If not Ebla, it is difficult to suggest any alternative explanation. If it is to be accepted as Ebla this does not mean that the map shows the area around that city. Ebla is in north Syria, just south of Aleppo, while Nuzi is in northern Iraq, south of Kirkuk. As BAD means “fortress” (Akkadian duru) it is possible that the reference is to a garrison of troops from Ebla stationed in the vicinity of Nuzi. The exact details of the map remain enigmatic.

It is also of interest that the Nuzi map specifies its orientation by naming three of the four cardinal points (the one on the right is missing), each given by the appropriate wind. Here the west wind is at the bottom of the map with east at the top and north on the left. The name of the south wind could then be restored on the missing right hand side of the map.

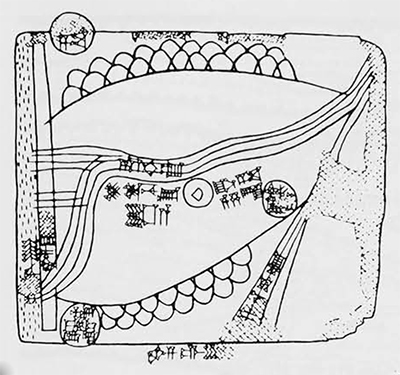

Some of the written information on the Nuzi map gives nothing more than the dimensions of fields, cultivated plots of land. However, the directional indications, the representation of streams and mountains, all indicate that this is more than an ordinary field map. Such field maps are rather well known. Shown here is an example from Kassite Nippur, dating to about 1300 B.C. It designates a number of privately owned fields, each recorded with the name of the owner, separated by streams and irrigation canals. In the center of the map is the king’s own field, described as “field between the canals, the holding of the palace.” On either side are the fields of the baru-priest.

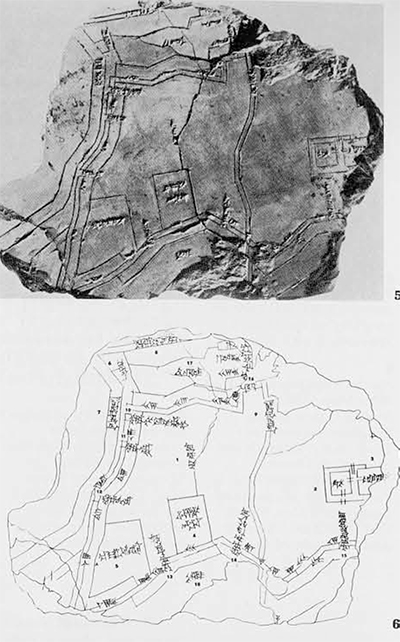

Of much greater interest is another map from Kassite Nippur, about a millennium later than the example from Nuzi. Here we have a map showing the city of Nippur itself. It was found during the original excavations at Nippur sponsored by the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, (four long seasons between 1889 and 1900) under the direction of H. V. Hilprecht. The map is presently part of the Hilprecht Collection at the Friedrich-Schiller University in Jena, Germany. It is shown here in photograph and in line drawing. The drawing has the features named on the map identified by numbers. These names, in Sumerian and Akkadian, label many elements shown on the map, including:

1. the name of the city, Nippur

2. the Ekur, foremost temple in the city

3. the Kiur, a temple subsidiary to the Ekur

5. the Kirishauru, the ‘Central Park’ of Nippur

7. the Euphrates river

9. the Idshauru, the ‘Central Canal’ of the city

10, 11, 12. three gates in the western wall of the city

13, 14, 15. three gates in the southern wall of the city

16. the single gate in the northern wall 17, 18. moats before the northern and southern walls of the city.

Here then is the city of Nippur in the second half of the second millennium B.C., shown as a well fortified site with moats, walls, gates and major architectural features. When the map was first published in 1905 it was considered to represent only the eastern part of the city and was shown turned 90 degrees, with the Ekur at the bottom of the map. This was because such an orientation best matched the excavated remains as they were then known. Recent excavation by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, under the direction of McGuire Gibson, has shown this to be incorrect, indicating that the map is to be read as shown here and that it represents the entire city.

This raises several problems in the history and archaeology of Nippur. Now the ‘Central Canal’ (literally ‘the canal in the heart of the city’) is to be identified with the present-day Shatt an-Nil, dividing the western and eastern mounds on the present site. The Euphrates must have originally run just west of the city, whereas today Nippur is far east of the modern course of the river. Moreover, something is now wrong with our interpretation of the Ekur as it has now been given a different orientation which does not seem to match the archaeological evidence. Such problems can only be answered by future excavation and further study.

The map of a city seems to have been the dominant type of cartography in ancient Mesopotamia. We know a great deal about the city of Babylon during the so-called Neo-Babylonian or Chaldean period (626-539 B.C.), but not through any actual map. Several fragments of such maps have survived, so we do know that there did exist ancient clay maps of Babylon. Our detailed knowledge of the topography of the city as it was in the sixth century B.C. comes, however, not from maps but from a written description of the city. We have a collection of clay tablets, written in Babylonian cuneiform, making up a series called “Topography of Babylon” (DIN•TIRK’ = Babilu), the name coming from the first line of the text. This text gives us the names of all the gates, walls, rivers and streets of the city along with much other information.

Although this text has been known for a long time, it was only in 1974 that new duplicates of the fifth tablet were published giving the chapels of Marduk (the chief god) and the streets of the city as well as a closing summary listing the six districts of the east bank (of the Tigris river) and the four districts of the west bank, all described as “ten districts whose surrounding fields are fertile.” If we compare this description with what is known through excavation we realize how much we have yet to learn about ancient Babylon.

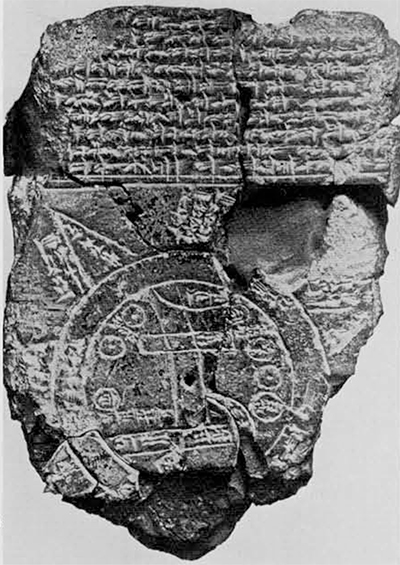

From about 600 B.C. comes one of our most famous clay maps, a Babylonian map of the world (mappa mundi), a text about which a great deal has been written, most of it nonsense. It is of ten said that the cuneiform text at the top of the map describes the conquests of Sargon of Akkad, but that is not true. The world is represented as a star, with the seven points of the star, starting from the lower right hand corner, making up the seven districts of the four quarters of the world. Inside the circle, surrounded by the ‘Bitter Waters’ is the city of Babylon, shown as a long rectangle, with the Assyrians east of Babylon and the Chaldeans (the tribe of Bit Jakin) to the southwest.

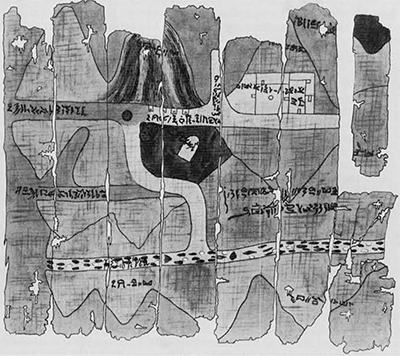

From pharaonic Egypt the most famous map is the gold mine map now in the Turin Museum in Italy. This papyrus map, dating from the reign of Seti I (1317-1304 B.C.) in the XIXth Dynasty shows a gold-mining area in the Eastern Desert, between the Nile and the Red Sea. The region depicted has been the subject of long debate, but it is now generally held to be the area between Quena and Qoseir on the Wadi Hammamat. To understand this map it is essential to understand that, like an ancient Chinese map, the Egyptian map is oriented with south at the top. This puts west at the right and east at the left hand side of the map. Thus the road shown running off to the left of the map is actually going east, to reach the Red Sea at Qoseir. This map, then, depicts part of the northernmost gold mining region of ancient Egypt, known as the Gold of Coptos. South of Aswan was the area producing the Gold of Wawat and then, between Semna and Kerma, came the Gold of Kush.

In the middle of the Turin papyrus is a white oval-shaped stele marked with the name of Seti I. To the left of this is a well, the modern Bir el-Hammamat. The white area, to our northeast, at the top of the map, is a temple of Ammon. North of the well and the stele are four small buildings shown at the top side of the road and described with a hieratic inscription reading “the houses where they wash the gold.”

As shown by this brief survey, the art of cartography underwent little development prior to the Christian era, It was only during the Roman Empire, beginning with the work of Claudius Ptolemy, in the second century A.D., that the western world developed a knowledge of the earth, and the heavens as well, that could equal that produced by the Chinese centuries earlier. The Almagest and Geographia of Ptolemy provided the basis for the knowledge of the earth and the heavens that surrounded it down to early modern times.