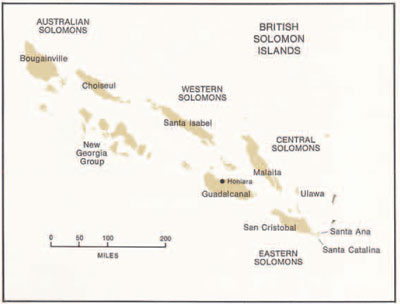

Since 1964 field research in the British Solomon Islands has been primarily concerned with ethnographic studies. Last winter’s special exhibition “Sculpture from the Eastern Solomon Islands” (see Expedition, Vol. 10, No. 2) was one result of these. However, as the contemporary cultural picture in this part of Oceania has become much clearer in the past two decades, we have become increasingly more interested in the history of the peoples and cultures. Because this is an area of the world where non-literate peoples survived in the present century, history here is only the history of European discovery and political annexation. The history of the local peoples is prehistory—archaeology, that is. Consequently, when I found a number of promising archaeological sites during my last ethnographic field trip (1965-66), I excavated some of them as a preliminary step in what is hoped will be a larger archaeological program in the years to come. In all, three small, shallow limestone caves and a midden were excavated on Santa Ana Island in the Eastern Solomons and another cave was dug on Guadalcanal Island in the Central Solomons.

The Santa Ana excavations revealed that this small island has been continuously occupied by man since before A.D. 40. The cave sites, which were probably used only as temporary shelters for fishing and marine collecting along the extensive reefs that ring the island, revealed increasing numbers of artifacts and shells and bones from edible seafood during this period. This may be an indication of a gradually increasing population. Pig bones were found throughout, indicating that the occupants had that domestic animal. The artifacts most frequently encountered were small blades of chalcedony ( a flint-like stone) which had to be imported from the neighboring island of San Cristobal. These blades are clearly related to those from New Britain Island described in Expedition, Vol. 8, No. 3, by Dr. Jane Goodale. The other artifacts found in large numbers were volcanic stones fractured by fire. These stones are the same as are used today by the local people to heat their earth ovens in which most of their food is cooked. Other objects included blades of giant clam shell for grating coconuts, whetstones of imported rock, and other objects of shell that are similar or identical to objects still made and used today.

The midden site yielded the same array of objects as were found in caves, plus a few more personal and household artifacts more closely associated with settled life in a hamlet (as contrasted with the specialized, temporary use of the caves). There are many more middens still to be excavated at some future date.

One of the most rewarding results of these small excavations was the discovery of a coarse, friable red pottery in the cave sites that dates between A.D. 140 and A.D. 675. Pottery is unknown on this island today; the people did not even recognize it as something man-made. However, pottery is known ethnographically some five hundred miles away in the Western Solomons, about the same distance to the south in the New Hebrides, and farther to the southwest in Fiji. The location of this early pottery in the Eastern Solomons connects these pottery localities and at the same time establishes a cultural horizon that indicates a change in technology. Why the Eastern Solomon Islanders gave up their pottery over one thousand years ago is cause for some speculation.

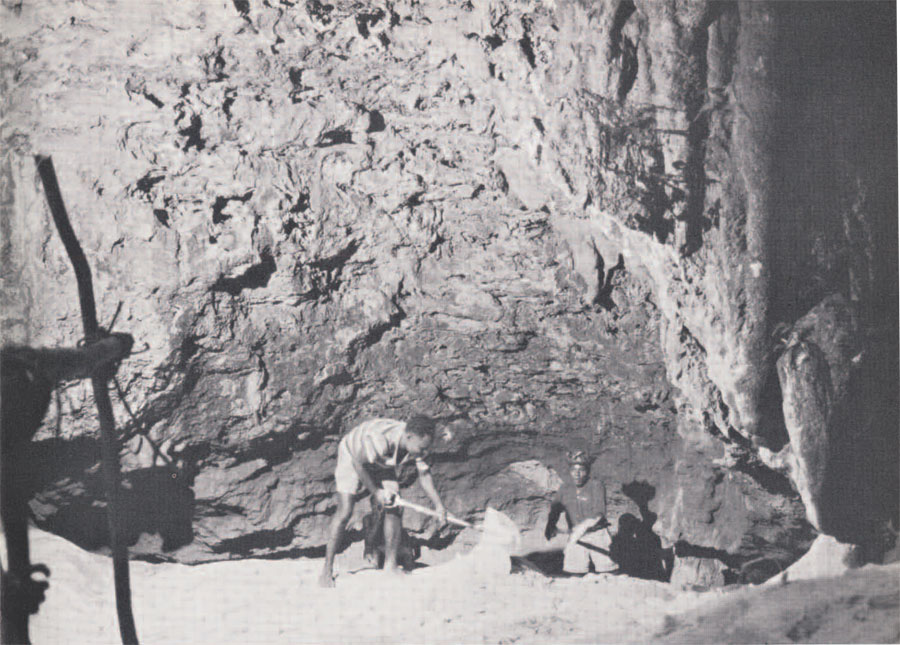

Results of the excavation on Guadalcanal Island have not yet been fully analyzed, so only preliminary observations can be summarized here. Started by me and finished by Messrs. Tom Russell and James Tedder, both of whom are officers in the British Solomon Islands Protectorate Government, the site was located in the Poha Valley of the north coast, a few miles west of the town of Honiara. It was along this coast and in these valleys that the Americans and Japanese were so long engaged in the World War II Battle for Guadalcanal.

The Poha Valley site was perfectly stratified into a series of superimposed occupation levels, each level clearly separated by layers of heavy rock that had fallen from the ceiling. The topmost level contained thousands of U.S. .45-caliber bullets, Japanese cartridge cases and ammunition boxes, a skeleton with which was associated a wallet containing pictures of two Oriental children, and other grisly reminders of the War. Twelve feet below, the lowest stratum contained no chalcedony chips, only intrusive sea shells, some of which might be crude artifacts, and charcoal. This charcoal has been dated at 970 B.C. Intervening strata showed an array of artifacts that gets increasingly varied by time, but no pottery was found at any level. The total inventory of artifacts was slightly different from those found on Santa Ana Island. The contemporary cultures of the two islands are, likewise, slightly different. Thus the Poha site shows nearly three thousand years of evolution of the local Guadalcanal version of Solomon Island culture.

In November and December 1967 Mr. and Mrs. Harry P. Whitney went to the Solomons to follow up some of these preliminary archaeological findings. They located more promising sites, made surface collections of stone tools, and studied the still extant but dying ceramic techniques of the peoples in the Western Solomons. Their work will enable us to classify stone tools by local styles and to compare the pottery making technique of the area where it has survived with that of the eastern islands where it was abandoned many generations ago.

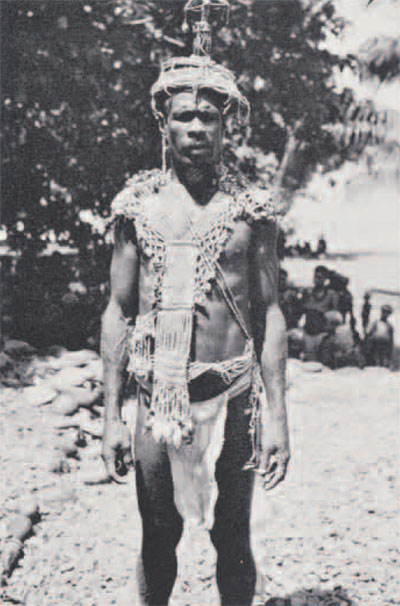

Across the high central mountains of Guadalcanal on the isolated south coast was a locale of special ethnographic interest. Although this area was not fought over during World War II as was the north coast, its closeness to the battlefield completely upset local village life for several years. Also the incredible spectacle of two mechanized armies of strangers from overseas locked in total war completely altered the conceptions that these peoples had of the world about them and their place within it. After the fighting was concluded and the armies had disappeared almost as mysteriously as they had arrived (leaving behind a wealth of material, the likes of which Solomon Islanders never imagined existed) there was general dissatisfaction and an outcry for change. A social movement combining political protest and millennium hopes for a richer life originated in another of the British Solomon Islands and swept across Guadalcanal. The British Government did what it could to cooperate with this movement and to redirect its goals toward established administrative objectives, but in the end the movement had to be forcible crushed, because it had become insurrectionist. During 1956 on Guadalcanal a prophet named Moro had a vision of a better way of life. Received from an ancient spirit of the island, this vision of a new life was to be a synthesis of the best of the old and the wealth and prosperity that the peoples of the industrialized world possessed. Quickly Moro’s message and social programs designed to attain the goals of his bidion swept across most of Guadalcanal to become a quasi-religious movement. The prophet’s village of Makaruka became headquarters for the movement. Changed considerable from the character of the first post-war movement, which became violent, the current movement stresses self-help through the pooling of local resources of all peoples of Guadal canal for a number of ambitious economic and political enterprises. This in itself was a great innovation for a people whose traditional political life never extended beyond the consolidation of more than a few hamlets.

In 1964 I crossed the mountains to visit Moro and hear about his vision and programs. The following year Mrs. Gulbun Coker O’Connor, a graduate student in anthropology, went to Makaruka to study the Moro Movement in detail. She remained there by herself for a year and obtained one of the richest accounts of such a social movement among a non-literate people that has ever been recorded. Currently, Mrs. O’Connor is preparing this data for her doctoral dissertation.

Social movements of this kind have been exceedingly common in Oceania and other parts of the contemporary primitive world during the last century. They seem to become even more frequent as the thrust of civilization disrupts the traditional equilibrium of social life. Some of them are exceedingly mystic and supernaturally oriented; others, like the recent Mau Mau of Kenya, are violent; while others, such as the Moro Movement, are largely materially and economically directed. Most, however, are combinations and permutations of all these directions with varying emphases. In all their varied and unique forms these movements can be seen as social responses that seek, through new ideologies, to reestablish some kind of social coherence for people whose lives have been irrevocable shattered and disrupted by the circumstances beyond their control. They are not social disorganization—although to the naive outsider they may appear to be chaotic—rather, they are abrupt attempts to give life dynamic new direction, a heightened sense of identity, and above all else an enhanced meaning and purpose. In emerging nations these movements may become the vehicles out of which parochial tribal and linguistic identities are broadened into national images or even political parties. It has been through the careful study of such social movements as these in primitive societies, along with those recorded in our own and other historical traditions of the world’s civilizations, that we have come to realize that orderly human life depends upon common ideologies. When, through progressive social change or mixing of alien ideas, these ideologies break down, prophets and innovators arise with new doctrines and novel formulae for living. Out of these are forged new ideological systems that become the bases for new periods of unity and stability.