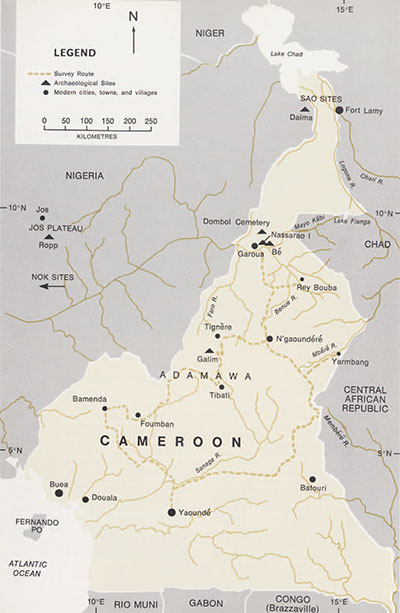

In spite of its central location at the hinge of Africa, between the Congo basin and the West, the desert and the equatorial forests, the archaeology of Cameroon is unknown and virtually unexplored. There is a single exception, the Iron Age culture of the Sao in the extreme north around the southern shores of Lake Chad, which has been investigated for many years by Professors Griaule and Lebeuf. In 1967 I made a brief archaeological reconnaissance, supported by a National Science Foundation Institutional Grant, in the central and northern parts of the country, guided by M. Eldridge Mohamadou, an ethnohistorian attached to the Federal Linguistic and Cultural Centre at Yaounde. M. Mohamadou, Fulani himself, specializes in the history and oral tradition of the Fulani and other peoples of North Cameroon. It is to him and to his knowledge of this area that our mission owes its success. The purpose of our survey was to find stratified sites relevant to the problems of the development of food production and of iron technology in Sub-Saharan Africa. Iron metallurgy is thought to have been introduced into this area in the last centuries B.C., as is suggested by dates from Taruga, a site of the Nok “figurine culture” in Nigeria excavated by Bernard Fagg, and from Nok itself. Shortly thereafter, iron may have been an important factor in enabling the pre- or proto-Bantu speaking peoples to penetrate the tropical forest during the course of their dramatic expansion into Central and Southern Africa from a homeland which the linguists Guthrie and Greenberg have suggested lies in the Central Benue-Lake Chad area.

The Cameroonian Government kindly lent us a Land-Rover, and we left Yaounde in the beginning of July, crossing the Sanaga River at the falls named after the great German explorer Nachtigal, and driving west to Bamenda in the old British Cameroons. There we turned north and climbed the scarp up onto the Adamawa massif, a high grassland, eroding under the pressure of grazing by the Zebu herds of the M’bororo’en, or pastoral Fulani. The M’bum, Baya, and other agricultural peoples of the massif practice shifting cultivation and move their villages, usually sited on the valley slopes, at varying but short intervals. We visited villages abandoned only a few decades ago, now only recognizable by the presence of mangoes and other planted trees. Even two years after its desertion little is visible of a village beyond low grass ridges marking collapsed mud walls, the odd worn-out quern, and a few potsherds. The rest of the material equipment has either been moved to the new site, has decayed, or has been washed away by the rains. Archaeological remains of earlier periods are thus most likely to be found in secondary position in the thick bodies of alluvium in the valley bottoms, except in special cases where erosion is naturally inhibited, as in small internal drainage basins like that of Lake Dang, 10 km. north of N’gaoundere. There would repay detailed survey.

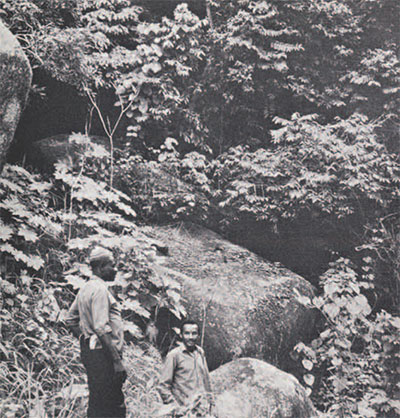

We had hoped to find caves, but none of any size or permanence are formed in the Pre-Cambrian and igneous rocks of the Adamawa, and, where they do exist, as at Galim, 35 km. SSE of Tignere, they are rather rock-shelters beneath and between huge granite boulders. The Galim site shows no evidence of occupation before the 19th century A.D., when a section of the Niam-Niam, fleeing the Fulani invasions, came south and built their village on the inaccessible Galim mountain. There they were able to withstand not only the Fulani, but also the later German colonizers, abandoning it for a more convenient location in the valley only after the First World War. Dr. Philip Leis of Brown University has recently made a study of these remarkable resistants. The old village is overgrown and is occupied only by a flourishing troop of baboons, but besides the potsherds that litter the sides of the mountain we saw the remains of the chief’s compound with one of its granaries still preserved, and many of the large granite boulders showed oval depressions where once the women of the village had ground their grain.

From Galim we travelled north and then east, via Ngaoundere, to Yarmbang, a village of semi-sedentary pastoral Fulani, a few miles from the borders of the Central African Republic. We were received by the Ardo Seyni and his family and spent the night under his roof, to their no doubt considerable inconvenience. That evening M. Mohamadou recorded Fulani tales and songs sung by the women and children. The next day, having neither seen nor heard of promising or even possible sites in the region, we went north to the most likely of the areas I had picked out on the map, the Upper Benue Valley.

From the steep scarp of the Adamawa, the Benue, the Faro, and their tributary rivers flow northwards through Cretaceous sandstones. East and west of Garoua there are Quaternary alluvial deposits 10 km. and more in width, and the present Benue flood-plain is about 4 km. wide. By mid-July the rains had already made some minor roads impassable, and with the exception of a brief excursion to a cemetery near Dombol discovered by the Department of Roads, where next year I hope to do a salvage dig, we were forced to concentrate our attention on the valleys of the Benue and the Mayo Kebi to the east of Garoua. This was no disadvantage; along 35 km. of river bank we identified no less than ten mounds, varying in size from Be, 1 km. long, 500 m. wide, and about 9 m. in height, to small mounds, 100 m. in maximum dimension. Many others are reported to exist in the Bibemi area further up the Mayo Kebi, and they very probably occur downstream of Garoua. It is not known how far they extend up the Benue; there are none near Rey Bouba on the Mayo Rey, 100 km. southeast of the Benue-Mayo Kebi confluence. The mounds are liberally scattered with potsherds; some are under millet and cotton cultivation, while others are still occupied. We decided to test on in order to determine whether it was artificial.

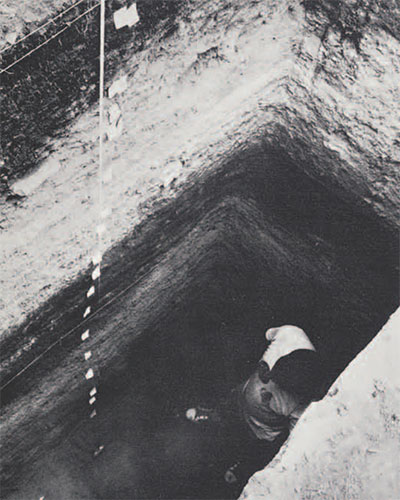

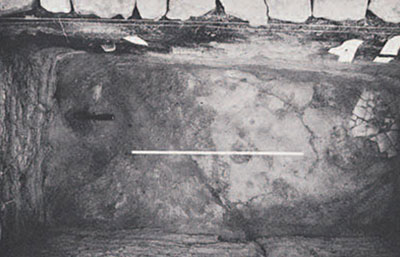

The site we chose and called Nassarao I, after a nearby village, is one of a cluster of five mounds, located 8 km. northeast of Garoua, to the south of the main Garoua-Maroua road. It is shaped like a saddle, measuring about 220 m. E-W, 660 m. N-S, and rising some 5 m., above the level of the Benue flood-plain. A small test-pit, dug at the highest point of the mound, revealed 3 m. of horizontally stratified floors and occupation debris, resting on a base of sterile, compacted sandy clay, perhaps a fragment of an old levee upon which the first inhabitants established themselves above the level of the floods. We excavated by arbitrary 20 cm. units except where there were well defined floors, numbering the levels 1-21 from top to bottom. Structural features included three pavements of potsherds, laid flat instead of on end as they are at Daima, Graham Connah’s great mound site in Bornu (reported in the Illustrated London News, Octover 14, 1967). Potsherd pavements occurred in the upper levels (2, 4, and 7), together with two fragmentary floors of chert concretions, (level 5). In the lower levels (8-17), there were many floors of beaten earth. We also found a pit and part of a hearth with a raised clay surround.

Faunal remains, remarkably well preserved, included freshwater mussel and oyster shells, large snails, tortoise, fish vertebrae, and mammal bones, as yet unidentified. Iron objects were recovered from all levels down to 17, but their absence below this is probably not significant. Beads and other fragments are now being restored. There are no axes, adzes, or hoes, but ground stone appears in the forms of a fragment of an oval lava quern, lava grindstones, crescentic in shape in the upper levels and narrower below, and sub-spherical multi-facetted rubbers of basalt and quartz, which appear from top to bottom of the site. Flakes of quartz and rare flaked tools, including a pebble pick and a steep end-scraper occur in and below level 3.

Preliminary study suggests no breaks in the sequence of pottery, which is abundant down to level 14. The pottery, tempered with coarse grit, is a well-fired, light buff ware with matt surfaces, varying in thickness from about 3 mm. to 2 cm. Variations in firing or smothering at a late stage of the firing may produce blackening, and some pieces were fired under reducing conditions. Many sherds are slipped or washed with colors ranging from pink to dark reddish brown; a considerable number of these are burnished, especially on or near the rim. Forms include the common “storage or cooking” pot with everted rim and rounded base, and bowls with simple or incurved rims, lip forms showing greater variation in the upper levels. Both classes cover a wide size range. There are also shallow platters up to an estimated 40 cm. in diameter, and occasional bottles. Applied features include vertical handles, tabs and lugs, and disc bases; surface finds suggest that footed vessels were made. Large pots may have a raised cordon pinched up around the shoulder, sometimes decorated with impression or punctation. cord-marking is the most common of a wide variety of decorative techniques, usually applied inbands around the rim, neck, or shoulder of the pot, the bands sometimes being delimited by shallow grooves. Other rouletted impressions include a fine chevron pattern, which appears only above level 10. There are many punctate designes and a little incision. Many rim sherds are decorated along the top of the rim with impressions, punctations or a shallow groove. Decoration is often incrusted with white pigment. I know of no parallels for this distinctive pottery, which differs both in its form and in decoration from that of the Sao near Lake Chad, whose culture is characterized like that of Nok be terracotta figurines. Graham Connah tells me that he sees some similarities to pottery from Daima dating to A.D. 1000 or later.

Upon arrival of the material in the United States, I discovered to my horror that the trunk had been rifled and the charcoal samples, collected from levels 14 and 20, destroyed. Thermoluminescence dates will be run, but until they are available, the site can only be attributed in general terms to the local Iron Age, though no trade goods or pipes were found that would indicate a 16th century or later date, and neither are quartz tools or iron beads known to have been manufactured recently. We can estimate the duration of occupation by comparison with sedimentation rates at Daima. This suggests that Nassarao I may have been occupied for well over 500 years.

The mounds are unfortified—since there is little wood, fortifications would of necessity have been of stone or clay—and very few compounds of the size usual today, about 400 square meters, could have been established on the smaller mounds. This pattern of settlement, combined with the apparently continuing tradition of pottery manufacture, suggests a long period of cultural continuity, unexpected in a region characterized historically by population movements, and lying at a crossroads of internal African lines of communication, where two major linguistic groups, Chadic and the Adamawa Eastern branch of Niger-Congo, come into contact. The most recent major intrusion took place in the first decades of the 19th century, when the Fulani drove out or conquered the Fali and other inhabitants of the Benue Valley. So a date of 1810 may perhaps be taken as a terminus ante quem for the abandonment of Nassarao I. Lebeuf and Masson Detourbet report an oral tradition that Be, the large mound 30 km. east of Garoua, was occupied in the early 18th century by Sao from the north. If this is so, it is not apparent from surface pottery we collected, which is very similar to that from Nassarao I. In summary, although the evidence is not nearly sufficient to prove peaceful conditions and cultural continuity, it may be read to suggest such a period, probably antedating historic migrations into the Benue basin. The region may at this time have been remote enough to have been little affected by the Hausa states to the west, and the kingdoms of Kanem-Bornu and Bagirmi to the north and east, or else it was sufficiently strong to resist them. This problem will be among those that we will be trying to solve during research planned, but not yet funded, for 1968-1970, when further excavations will be undertaken at Be and other sites. The Lamido (Chief) of Be has offered us his aid in digging this magnificent site, which promises to go back further in time than Nassarao I.

Besides the archaeology, I will also be studying the material culture of the village that still occupies a part of the mound. This will offer up the chance for controlled comparison between the present villagers and the prehistoric inhabitants, and will be of enormous help in bridging the gap between artifacts and basic social and cultural units like the household—always such a problem for the archaeologist working in an area where there is no continuity either of the people themselves or in the ways and means of making a living.

- A part of the mound at Be’ rising out of the flood-plain of the Mayo Kébi (left). M. Mohamadou and a group of young initiates are collecting potsherds.

- Puddling through the marsh on the way back from the Nassarao I village mound.

- The test-pit at Nassarao I, ringed with flat stones to remind everyone to keep off the edges of the section. The young Fulani ladies were not employed at the site, but are merely visiting.

- From right to left: potsherds, an iron bead and a point fragment, fishbones, teeth, bones and shells from level 15. Preservation of organic remains was excellent, a comparative rarity in Africa.

- Pottery from Nassarao I.

- Pottery from Nassarao I.

- Pottery from Nassarao I.

- Pottery collected from the surface of Bé mound.

I would like to end by saying how grateful I am for the interest, encouragements, and support that I received from many Cameroonians, especially the Minister of Education, M.W. Eteki-Mboumoua, and Father Engelbert Mveng, Director of the Federal Cultural Centre and author of the Histoire du Cameroun. It is a real pleasure for an archaeologist to work in a country where everyone, from senior government officials to my workmen (whom I was giving [at their request!] lectures on stratigraphy during the dinner break), really wants to know what happened before the start of recorded history.