Letters are crossing a museum curator’s desk constantly from different and obscure parts of the globe telling of chance discoveries and requesting information as to the age, origin, or meaning of whatever happens to have been found. Usually the writer is an amateur collector who only vaguely describes the object at hand and almost never provides a sketch or snapshot of it. Nor in the case of multiple finds does he normally trouble to record which objects were found together. The lack of these two elementary pieces of information–an adequate illustration of the finds and a knowledge of which objects went together–makes the curator’s task much more difficult. Worse still, the omission of a few scribbled notes often means the loss of historical information of real value.

Letters are crossing a museum curator’s desk constantly from different and obscure parts of the globe telling of chance discoveries and requesting information as to the age, origin, or meaning of whatever happens to have been found. Usually the writer is an amateur collector who only vaguely describes the object at hand and almost never provides a sketch or snapshot of it. Nor in the case of multiple finds does he normally trouble to record which objects were found together. The lack of these two elementary pieces of information–an adequate illustration of the finds and a knowledge of which objects went together–makes the curator’s task much more difficult. Worse still, the omission of a few scribbled notes often means the loss of historical information of real value.

Under such circumstances, the amateur has an opportunity to contribute in an important way to the field of archaeology whenever he visits a known or a new site, or observes chance discoveries made in areas disturbed by clandestine digging, road building, canal digging, and so forth. The recovery of whatever “archaeological scrap” may be at hand, usually thrown out by the operation itself as irrelevant to its purposes, and its recording in the form of a few notes on where and when it was found and in what circumstances may yield significant historical data when submitted to a specialist in the area of discovery.

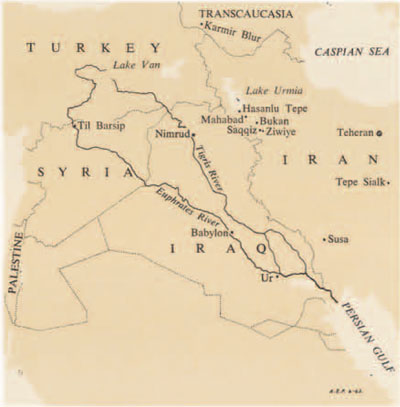

Let us take a case in point. In 1947, according to local reports, a shepherd made a chance discovery of a bronze or copper chest or coffin containing a treasure of gold washing out of the side of a small mountain in central Kurdistan, Iran. The local village of Ziwiye, not far from the town of Saqqiz, gave its name to this hoard which is sometimes also referred to as the Treasure of Saqqiz. Pieces soon made their way into the antique market after being divided, cut up, or melted down by the discoverers. A selection of it was acquired by the Archaeological Museum in Teheran where it is now displayed. Other pieces or parts of pieces are now to be seen in a number of major museums in Europe and America including our own University Museum (University Museum Bulletin, 1957).

Since its discovery, as might be expected, this collection of gold objects has been the center of an active discussion involving its stylistic origins and date. Such scholars as Andre Godard, former Director of the Archaeological Service of Iran (Le Tresor de Ziwiye, 1950), Roman Ghirshman, Director of the French Archaeological Mission in Iran (Artibus Asiae, 1950), Helene Kantor, Professor at the Oriental Institute of the University of chicago (Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 1960), Charles K. Wilkinson, Curator of the Metropolitan Museum’s Near Eastern Department (Iraq, 1960), and R.D. Barnett, Curator of the Department of Western Asiatic Antiquities in the British Museum, (Iranica Antiqua, 1962) have written authoritatively on these questions. Individual pieces have been attributed to the Assyrians, Urarteans, Scythians, and Medes. It has even been suggested that some of it may represent the work of the local inhabitants, the Mannaeans! The dates suggested range from the ninth through the seventh century B.C. As should be expected in the case of such troves as these, all of these allegations are likely to be true to some extent since such a hoard is normally composed of a variety of highly prized pieces and heirlooms.

Yet with all of the excitement over the treasure itself, and the accompanying argument as to whether it did indeed all come from Ziwiye as alleged, relatively little attention was paid by specialists to the site itself, located at the top of a small three hundred foot high mountain which towers over the local valley with its fine spring. From the summit there is a commanding view in all directions toward the neighboring mountains. The ascent is steep and only the stout of heart make it to the top which lies at an altitude of about six thousand feet above sea level. Others turn back to wait in the shade below. From that vantage point the top of the hill looks like any respectable hill with rocky outcrops. One would never dream that a site was located there just waiting to be dug into. In fact, even when walking around on the surface one has to look very sharply to observe the potsherds washing out of the grass covered with soil.

During the course of our seven years’ work at Hasanlu Tepe, several hours’ drive northwest of Ziwiye near the southern shore of Lake Urmia, we visited the mountain top on several occasions. During our first year’s survey in 1956, Jason Paige, our Iranian Archaeological Inspector Taghi Assefi, and I paid a visit to the village. We camped in the landlord’s orchard for two days and spent a good deal of time on top of the mountain examining the dumps of several small excavations being conducted by the villagers for an agent (then in Saqqiz) of the well known Teheran dealer Rabinou. (At that time commercial digging permits were legally issued by the Iranian Government for specific sites; the practice is now suspended.)

None of the men digging understood the nature of the deposit; they were simply cutting small neat squares into the slope indiscriminately slicing through brickwork and fill. When questioned, they reported that they had been performing this kind of work since 1947 when the hoard had been found, without adding anything of significance to the collection. They voluntarily pointed out the spot where the chest had allegedly been found, about halfway down the slope away from the village spring side in a deep gully. At the time, there had been almost no visits by foreign archaeologists to the site and it seems improbable that these local villagers would have bothered lying to us in the absence of the interested parties, or, for that matter, that the dealer would have been spending money excavating unless some discoveries had been made there. Whether all of the objects since attributed to the find came from here or not is open to question. A few are now known definitely to be from elsewhere. Ziwiye thus joins numerous other famous sites used as a foil for the real location of new finds.

From this first visit we acquired a few typical sherds from the dumps and one or two bits of corroded copper. On another occasion in 1960, a group of us went from Hasanlu to see what had been done to the site since 1956 and to collect a few more sherds for study purposes. Two of the authorities most interested in the stylistic problems of the gold accompanied us: Dr. Edith Porada of Columbia University and Dr. Helene Kantor of the University of Chicago. The trip was made through a golden countryside already busily harvesting its grain. It was drier than in 1956 when in June we had had to ford the small local river to get into the valley. In 1960, the dry cycle had progressed to the point where in July the river no longer flowed (just as the small fresh water lake near Hasanlu had disappeared). The drive is a long tiring one, taking about six hours from Hasanlu via Mahabad, Bukan, and Saqqiz. We broke it after crossing the dry river with a luncheon picnic under a sprinkling of shade provided by a scantily clad tree. It was blazing hot and thoroughly dry, and after such a long ride in an open truck, terribly dusty as well. Dr. Porada made a welcome discovery. Soon the ladies were luxuriating in the coolness of discarded cucumber skins draped across their bare legs! Cucumbers in Iran are an essential item providing a watery food (which is sweet and not bitter as in America) and, as it turned out, coolness as well.

The second visit, and others, provided a good sized collection of “scrap” consisting of potsherds and odds and ends of stone and corrosion. From this scrap, collected over the site and from the commercial dumps, and from a few observations on the site itself, it is possible to add significantly to what is known about the site and its history without ever lifting a spadeful of earth.

For example, the site was referred to by Godard as probably being Zibie, one of two strong Mannaean fortresses destroyed by Sargon of Assyria along with Izirtu, the capital city of the Mannaeans, in the eighth century B.C. A visit to the cramped top of the mountain shows that it was so restricted that there is no possibility of considering it a city or a town, although it might still have been the citadel residence of the ruler. Its position and size confirm the assertion that it was a citadel–perched on the crest of the hill and defended by mud brick walls towering above the naturally steep ascent. The structure itself appears to have been stepped in at least three stages: a lower rather triangular area at one end, a second level higher up, and a much smaller and very high third level. The latter was strewn with the fragments of large jars, indicating some kind of storage area.

Had there been no disturbance of the mound, that would have been all that we could have said. Fortunately the previous digging activities had uncovered a number of fragments of mud brick walls built of large square bricks (34 x 34 x 9 cm.). None of the exposures showed any evidences of multiple floor levels or rebuilding–but then, they were all of very limited size. One long trench cut down the side of the mound away from Ziwiye village (which lies on the valley bottom near the spring a short distance away from the hill) revealed two large round limestone column bases, while a third had been rolled down the mountain and could be seen lying in the field below. These bases, which are simple drums in form with a single flaring “collar” around the base, undoubtedly supported wooden columns in a portico or hall of a very grand building. In the disturbed fill of the same area were fragments of triangular wall tiles in plain terracotta as well as glazed white, yellow, or blue. Similar glazed wall tiles were used in the palatial buildings of Assyria beyond the mountains to the west and at Susa beyond the mountains to the south.

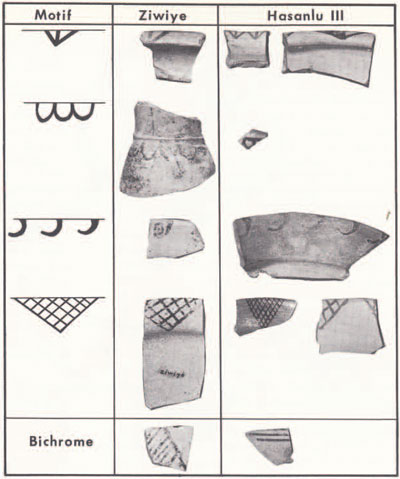

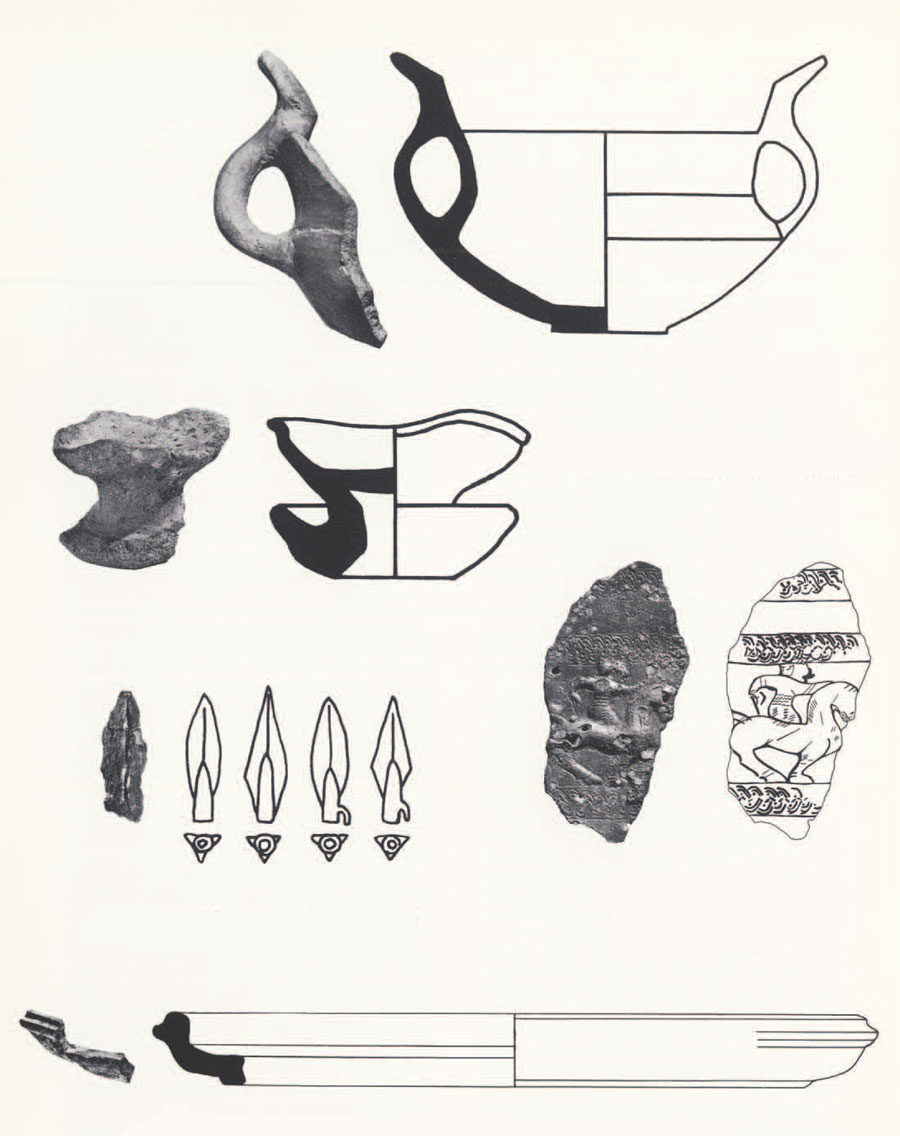

Among the masses of broken pottery lying about, we collected a representative sample, trying to find as many shapes as possible as shown by rim and other diagnostic pieces such as handles, spouts, and so forth. The pottery, which includes both a fine and a coarse ware, is largely buff colored with rare red slipped sherds and some highly polished sherds. The latter fire to a lovely almost white color (but range through orange-red to buff on a single sherd where the firing temperature was uneven). Most of the pieces found looked quite different from those being recovered at Hasanlu. This is especially true of pottery decorated with incised hanging triangles which is unknown at Hasanlu but one piece of which has been found far to the northwest at Lake Van in eastern Turkey. Other shapes looked more familiar however. Among these were spouts with long horizontal beaks attached to the rim of the vessel by a kind of bridge, and curious “tab handles” which suggest metal rather than ceramic forms. Both of these forms are typical of Period IV at Hasanlu which ended in a great fire in the late ninth century. At Hasanlu the forms are better made, far more common, and occur in burnished grey and polished black ware. The forms at Ziwiye appear to be decadent later versions of these types.

Mixed in with the masses of broken plainware sherds, but quite rare, were finely made painted sherds. The geometric designs included hanging triangles and a “hanging curl” pattern. To our surprise we have found that we can match almost every one of these sherds with pieces from Hasanlu III dated with two radiocarbon samples to around 622 B.C. But at Hasanlu the tab handle and spouted forms seem already to have disappeared. It would look, therefore, as though the Ziwiye pottery might be slightly older than the assemblage at Hasanlu, falling between Periods IV and III, or between the early eighth century and the late seventh century B.C. Ziwiye by this calculation would thus date to the period of intrusions by both Urarteans and Scythians into this part of Iran. It is possible that this circumstance may eventually explain the otherwise unique aspects of the Ziwiye sherds.

Besides the sherds, we also recovered the remains of a pottery lamp. It is made of coarse, sand-tempered buff pottery and has some evidence of burning on the rim where the shallow bowl containing the oil and wick was scorched. This particular specimen, broken as it is, finds an exact parallel in the lamps recently excavated at the Assyrian city Nimrud by Professor Mallowan. Since these Nimrud lamps are firmly dated as Late Assyrian, we find further confirmation of a date in the seventh century as well as additional evidence of Assyrian influence in the Kurdistan area.

A sherd of a “tab handle” pot from Ziwiye compared to a drawing of a Hasanlu IV pot;

Pottery lamp from Ziwiye and drawing of Late Assyrian lamp found at Nimrud; Three-winged bronze arrowhead compared to Scythian arrowheads from Karmir Blur; Fragment of copper belt ornamental plaque (?) from Ziwiye and a drawing of the design; Fragment of a stone bowl from Ziwiye and a drawing showing its original form.

Small fragments of stone bowls also turned up among our “scrap.” These included both a white limestone variety and several dark marble-like stones of greenish color. The bowls had flat bases and short ledge-like handles. While visiting Philadelphia to receive his Lucy Wharton Drexel Medal from the Museum, Dr. Mallowan identified these as being Late Assyrian in type since they were comparable to ones he had excavated at Nimrud. In view of the quantity of later Achaemenian stone bowls, one wonders whether the traditions of working in these hard stones may not have had an Assyrian source. In any event, the late seventh century date for the site is again confirmed.

Another group of surface “scrap” was made up of formless pieces of copper corrosion. On the chance that they might tell us something when cleaned, or at least provide possible material for the analysis of trace elements which might aid in the study of the ancient metal trade, the were brought home. The effort to save these unattractive bits paid handsome results in terms of new information.

One piece was part of a bracelet showing a little decoration. Another was a fragment of a rectangular copper scale armor section with raised central rib and holes for attachment to a garment. Such armor, made of overlapping scales, was in common use by the Urarteans and Assyrians in these centuries, and has also been found at Hasanlu in the ninth century level (IV). More important, however, was the recovery of a three-winged, socketed arrowhead of the type commonly associated with the Scythians in the Near East and South Russia. Their earliest occurrence in the area is in Transcaucasian graves of the late eighth to early seventh century B.C. Shortly after this they appear vaguely dated to the seventh century in Iran, Syria, and Palestine. This style of arrowhead is found in large quantities at the Urartean site of Karmir Blur (in the Soviet Union) which was sacked by the Scythians in the late seventh century. The occurrence of three of them at Tepe Sialk in central Iran in the fill in which the graves of Cemetery B are dug is also of special interest, since that culture usually has been dated to the ninth to eighth centuries by the excavator. At a minimum, these arrowheads establish a terminus post quem date of about 750 B.C. for at least part of the occupation of both Sialk and Ziwiye.

We learned subsequently that another visitor to the site, Colonel Smith, had also found one of these bronze arrowheads. Ghirshman in his recent report on the Persian Village at Susa has published three others which he asserts belong to the Saqqiz Treasure and which are listed as being from a private collection. One may only wonder whether these are not similarly derived in fact from the excavations father than from actual association with gold objects.

The relationship of the arrowheads to the gold hoard is an interesting subject in view of the “Scythian” stylistic elements in a number of the gold pieces in that hoard. A date of late eighth to seventh centuries for the appearance of these arrowheads in the area is supported by the excavations at Hasanlu where no such arrowheads have so far been found in Period IV (about 1050-800 B.C.) whereas one isolated example was recovered from the fill associated with Period IV (about 622-440 B.C.). This relative occurrence is well suited to the evidence already described above for the pottery parallels. Thus, once again, the materials at Ziwiye would appear to be later than Hasanlu IB with its burnished grey pottery and golden bowl.

A small link to the style of the latter occurs, however, in the form of a small fragment of copper decorated with chasing and slight repousse work recovered from Ziwiye. Returned from its amorphous state by Eric Parkinson, the Museum chemist, this piece of “scrap” reveals a horse and rider in full gallop passing between borders in the form of complex guilloches. The fragment is very small and the surface not very detailed. Nevertheless, a few features may be determined through the use of side lighting, and we present here a tracing of a photograph of the object augmented by visual inspection to show the maximum available information. The guilloche borders are made by a series of dots and short straight lines made by a small chisel-like tool. The effect produced is comparable to similar guilloches found on two belt attachments from Period IV at Hasanlu. The horse at gallop reminds one of the Assyrian wall painting from Til Barship in Syria where the front and rear legs are stretched full out in the same manner (the painting dates to the seventh century). The figure of the rider is, on the other hand, purely Iranian in its seated position. No legs are indicated in any way on the original piece. In this respect it resembles the lady riding the lion on the Hasanlu Gold Bowl which, in turn, has its antecedents in the clay figures of a thousand years earlier at Susa. The vitality of the figure on the little piece of copper stands in startling contrast to the formalized gold renderings. One wonders if here we are not looking at the more local and native tradition–a piece perhaps of Mannaean workmanship.

Who knows, perhaps another visit some day, and another handful of “scrap” will help us to answer this and other questions.