Penn Museum archaeologists entered the Eastern Mediterranean region within an atmosphere of imperialism. Most of the material in the Eastern Mediterranean Gallery came from expeditions spanning the 1920s to the 1980s, periods that saw the contentious drawing and redrawing of political, economic, and community boundaries amidst the fallout of two world wars, multiple regional wars, and a cascade of national independence movements.

Analyzing the archives, and contextualizing their creation, sheds light on the ways archaeology was made possible by and contributed to the legacy of colonialism and empire in the region. This legacy continues to play a strong role in the way many people conceptualize the Eastern Mediterranean’s ancient past and contemplate the future.

After World War I, the League of Nations oversaw the British and French Mandate governments carve up the remaining Ottoman Empire. The Penn Museum was the first American institution to dig in what became British Mandate Palestine (today’s Israel and the Palestinian Territories) at the site of Beth Shean.

The Beth Shean excavation was instrumental in both the colonial practices of the British Mandate and in the rise of American Biblical archaeology. The excavation’s relationship with imperialism rested on everything from the colonial labor system archaeologists put in place, to the ways they formulated research goals and interpreted the material they found.

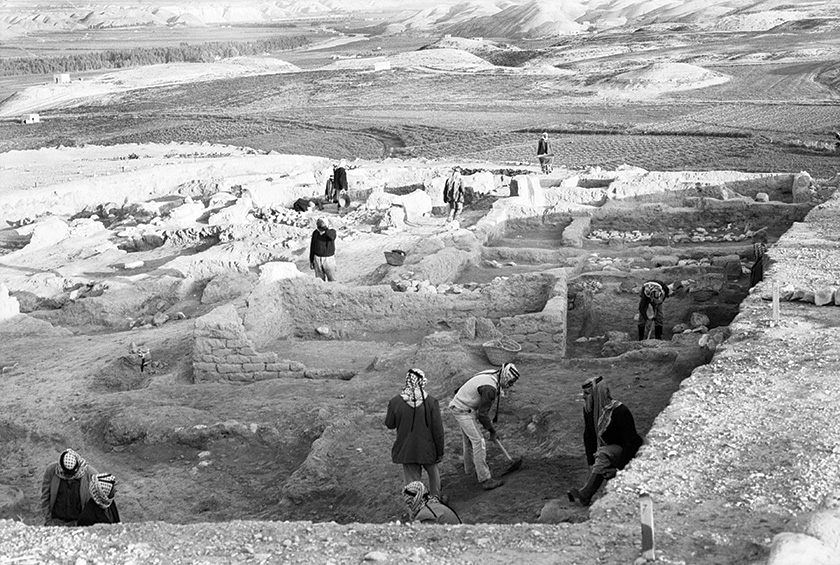

Labor in Palestine

Already digging in British colonial Egypt at Mit Rahineh (Memphis), Clarence Fisher led the Museum’s move to Palestine. Fisher chose Tell el-Husn, near the modern village of Beisan (Beth Shean in Arabic), because it was known from Biblical, Egyptian, and Classical sources. Its imposing, intact mound also signaled the potential to produce the exhibition-quality artifacts the Museum wanted and feared it might soon lose access to in Egypt due to the 1919 revolution against Britain. Eager telegram requests by Fisher to dig at Beisan circulated among British military administrators the same year, several months before the Palestine Civil Government coalesced in 1920. Under the Antiquities Ordinance of 1920, ownership and oversight of Palestine’s cultural heritage passed from the Ottoman Imperial Museum in Constantinople to the British-led civil government. Ottoman laws, previously stringent toward foreign nationals, were amended to ease site access and artifact export for American and European projects.

With permit in hand by spring 1921, Fisher was faced with starting a new project in a still war-scarred landscape. He sought quickly to reproduce the colonial labor infrastructure already well established in Egypt and Mesopotamia that relied on hired teams of workers to do the earth moving.

This was accomplished literally by moving dozens of Egyptian foremen and workers from his dig at Mit Rahineh to Beisan, as Fisher and George Reisner had done previously when digging at Samaria before WWI. Through the 1930s Western-led archaeological projects, like at Beth Shemesh, Megiddo, Jerash, and Tell en-Nasbeh, would seek out the experience of Fisher and the skilled Egyptian crew on which he relied to help open their own operations. Fisher’s method of excavation became a common model for running a project, enshrined in the research program of the American School of Overseas Research he later co-authored with William Albright.

On any given week, the Beth Shean expedition employed 25 to 250 Palestinian Arab men, women, and children to work under the Egyptian foremen. A meager daily wage supplemented their primarily agro-pastoral lifestyle and often took advantage of their precarious political and economic position since the War’s end. For example, the directors’ diaries record occasional, mostly unsuccessful, labor strikes. The first strike came in April 1923 when Fisher lowered wages to hire more workers. Fisher stood firm anticipating that a recent drought would push the locals to accept anything.

Stretching labor wages was common even for an unusually well-funded project like the Museum’s. Much of the over $200,000 (in today’s value) seasonal budget went to salaries for a director as well as the staff, a team of typically Western-educated specialists that included surveyors, illustrators, and object registrars. Specialist positions were filled by a rotating cast of experts with diverse backgrounds including educated Egyptians, former British, Turkish and Russian military servicemen, and recently emigrated Jewish scholars.

Non-Western staff members played an especially crucial role as the intermediaries between the foreign staff and the local workforce. Labib Sorial, a Coptic Egyptian, stands out as an example. Dr. Jeffrey Zorn has recently illuminated Sorial’s career as part of a history of the Tell en-Nasbeh excavations. Recruited by Fisher, Sorial became a fixture in Palestinian archaeology working nine different digs between 1921 and 1935. Though uncredited in subsequent publications, the Beth Shean archives shows Sorial performing the work of an assistant director. He supervised foremen, negotiated with and distributed payment to local laborers, organized project logistics, drew architectural plans, and much more. From piecing together their scattered references in project archives, more stories like Sorial’s are now coming to light to acknowledge the perspective and pivotal contributions of non-Western workers and staff in the colonial-era.

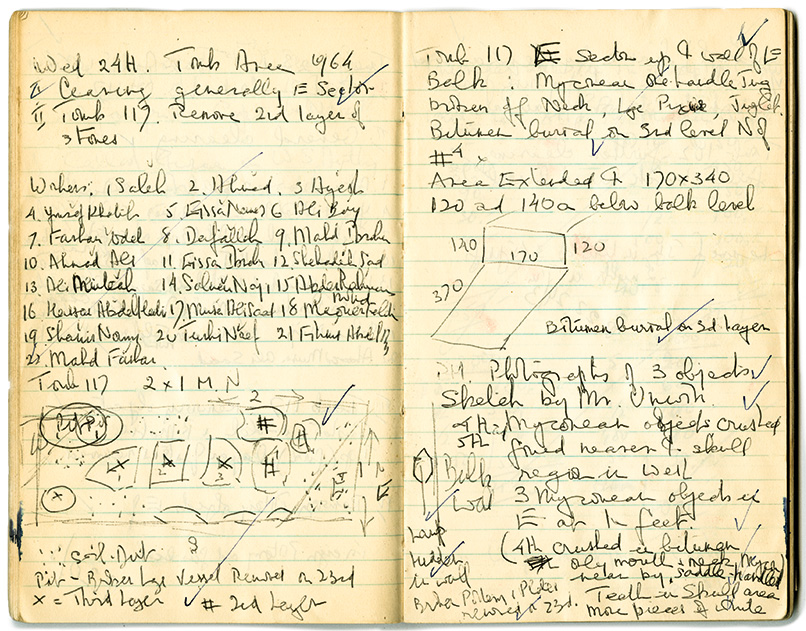

In the Eastern Mediterranean Gallery, visitors can examine copies of photos, diary entries, letters, and more from three excavations which created the collections on display; Beth Shean, Kourion, and Gibeon. The Archive Panel contributes to the “Crossroads” theme of the gallery by painting a fuller picture of the circumstances in which collections were formed, including the diverse backgrounds, skills, labor, and expertise of those who comprised the excavation teams, the motivations of researchers and project funders, and the complicated ways in which all involved intersected with period geopolitics.

The Land and the Mosquito

When Fisher arrived in Beisan, followed by Sorial and the Egyptian crew, much of their daily routines were determined by the Anopheles mosquito. The malaria-carrying insect was a widespread danger in Palestine especially to foreign visitors, and the marshy area around Beisan had a reputation for being particularly malarious.

Along with the excavation permit, the Palestine government provided instructions on where the project should place its camp, the care of mosquito nets, the proper daily dosage of the malaria drug, quinine, as well as a recommended curfew. Regardless of attempts to avoid infections, letters and diary entries over the course of the excavation contain lists of ill team members and frequent trips to hospitals in Haifa.

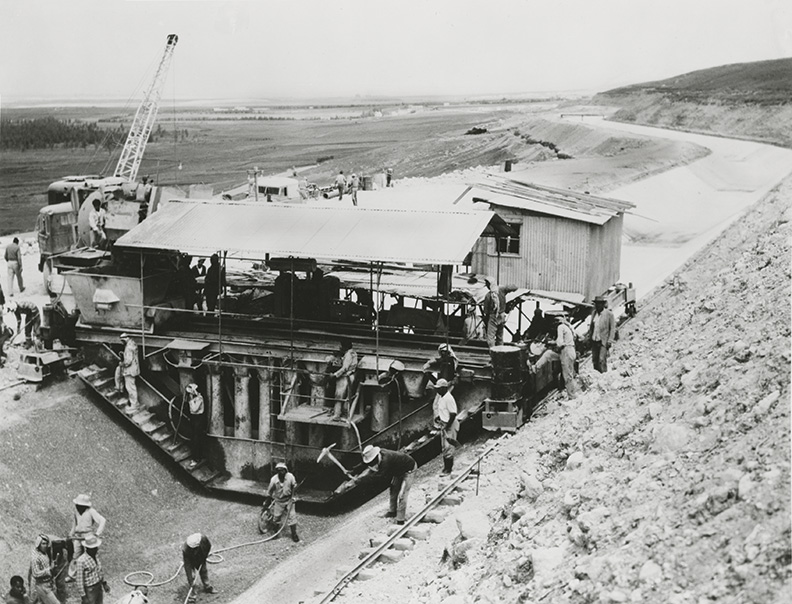

After the first year, avoidance measures gave way to action and attention was turned to cutting canals and draining the marshes around the site to reduce mosquito breeding grounds. While framed as increasing safety for the dig team and neighboring village, anti-malaria campaigns jointly carried out between the expedition and the health department contributed to the broader nation-making aims of the Mandate.

From the Mandate’s perspective, transforming the land and the local epidemiology was necessary to control Palestine, ensure the region’s capacity to sustain new Jewish settlement, and was ultimately to the Arab’s civilizational progress and benefit. A variety of different land, water, and health policies had the effect of disrupting the lifeways of most native Palestinians, especially nomadic pastoralists. The policies were often supported by widely held, colonial myths, which cast them and their approaches to land use as inherently unchanging and wasteful.

In all, the expedition’s anti-malarial work was small, centered on canalizing the Jalud River that wrapped around the ancient mound. But since canals require continued maintenance, and the project’s rotating foreign staff were always at risk, the disease became a prominent vector along which cultural and racial boundaries on the dig were reinforced. In several letters, Alan Rowe, an Australian archaeologist who succeeded Fisher as director, reports to Mandate authorities how he felt the local Arabs were making the malaria situation worse through their misuse of the canal and their generally “very careless” use of water. These letters, along with others that describe Rowe punishing workers he thought were not abiding by prevention measures, illustrate that his concern was about maintaining productivity as much as safety. They also show the biases with which he treated non-Western workers in enforcing a new vision of land and health management.

Lest the Anopheles mosquito seem too separate from the archaeology, Clarence Fisher explicitly tied the malarious conditions of the 1920s to the Islamic conquerors of Beisan in 634 CE. In their wake he imagined the destruction of the previous Byzantine city’s dams and that the once prosperous agricultural fields were flooded and left to turn pestilent. He assured readers of the 1923 Museum Bulletin that under the influence of the British Mandate, Beth Shean “may once more climb to its deserved height as the great city… of the Jezreel Valley.” Recent investigations have since demonstrated a peaceful transition to Islamic rule. Though diminished after a 749 CE earthquake, the city continued to be an industrial hub for glass and eventually refined sugar in the medieval period. Fisher’s biased story joins many, which underwrote the emphasis behind Biblical archaeology among Western scholars, led to the dismissal of Arab cultural heritage and Islamic heritage more broadly, and assisted the creation of a national narrative that justified European expansion.

Leading With the Word

When Penn Museum officers promoted their expedition to Palestine they led with the Bible. Philadelphians tuning in to WCAU radio in 1930 might have heard the voice of Cornelia Loring Dam, the Museum’s Head of Education, giving an update and quoting from the First Chronicles story of King Saul’s death and the display of his body on Beth Shean’s city walls. Dam continued “if you know your Bible you will remember that news of the calamity was brought to David who sallied forth to wreak vengeance. He captured the citadel of Beth-Shan and destroyed it—how thoroughly we could read in the excavations, where mud-brick walls had been baked red by the heat of the conflagration.”

The claim to evidence of David’s conquest was short-lived, generating as much skepticism and debate among scholars then as interest from the public. Nevertheless, Dam’s broadcast exemplifies over a decade of headlines promoting the “holy relics” being discovered at Beth Shean and the rise of a new kind of Biblical archaeology.

Research illuminating the lifeworld of the Bible had been carried out for decades before WWI. Mostly sponsored by French, German, and British national-scientific organizations, excavations and surveys often served the dual purpose of “Biblical exploration” and military reconnaissance intended to aid in staking claim to Ottoman territories once the empire ultimately dissolved. Indeed, the borders of Mandate Palestine were essentially those mapped by the British Palestine Exploration Fund since the 1870s under the cover of illustrating the Old and New Testaments. Thus began a territorializing of the Bible and a reframing of the region as belonging to principally Jewish and Christian heritage.

American scholars were relative latecomers to Biblical archaeology at the turn of the 20th century. Their research was stimulated by intense debates about the authenticity of Biblical history. Even before the dig began, the Museum advertised to the public and donors that archaeology in Palestine was important because of its Biblical connections. The primary goal of finding museum-quality artifacts related to Biblical stories was set from the beginning and heavily biased the interpretations of researchers. As big, privately funded projects like at Beth Shean and later Megiddo announced evidence for David’s destruction of Beth Shean or King Solomon’s stables, they contributed to the solidification and legitimacy of a new paradigm. During this “Golden Age” of archaeology, William F. Albright, a contemporary and mentee of Clarence Fisher, would define a distinctly American research outlook insisting that the Bible was essentially true as a historical document and that archaeology was proving it.

The financial and popular dominance of this outlook would persist through the 1960s. It would have far-reaching consequences as the land around Biblical sites and artifacts increasingly became pulled into nationalizing narratives that justified both the British Mandate’s claim to the region and that of the nascent Jewish State they supported under the Balfour Declaration.

The Penn Museum in the Eastern Mediterranean

1921–1933: Beth Shean, Mandate Palestine

By the 1933 season, then directed by Gerald M. Fitzgerald, the financial strain of the Great Depression, rising political unrest, and the diminished recovery of Biblical Period artifacts combined to discourage the Penn Museum from continuing work. The prospect of returning to Beisan was not officially called off, though, until 1938 at the height of the Great Palestinian Revolt against the British Mandate administration.

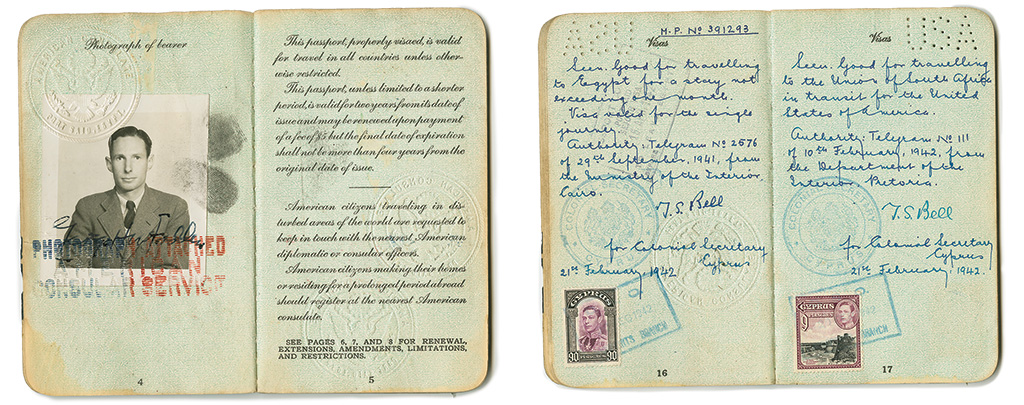

1934–1954: Kourion, Cyprus

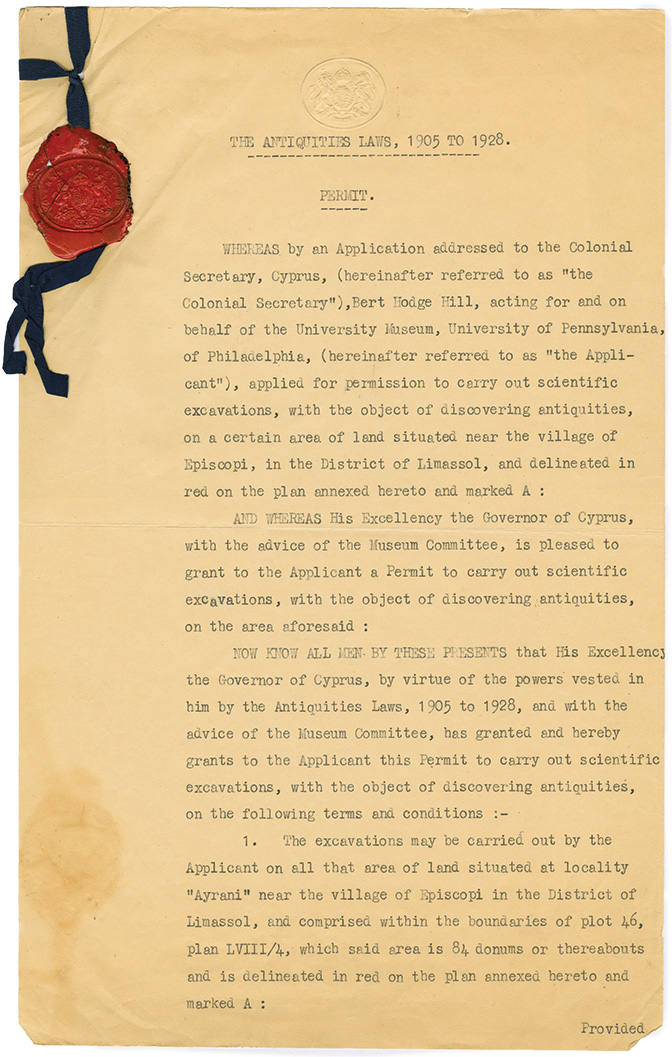

Kourion was one of the great ancient city-kingdoms of Cyprus. Over twenty years, with a pause for World War II, the Penn expedition uncovered over 5,000 years of human occupation. Their finds ranged from Neolithic settlements (4000s BCE) to stunning mosaic floors of the Late Roman and Byzantine periods (400s CE).

Cyprus had just recently become a Crown Colony when the British-led Department of Antiquities approved the Museum’s request to dig in 1934. The project was made possible by the exclusive support of George H. McFadden, III. Bert Hodge Hill, who already served the Museum at Lapithos, Cyprus, was contracted to direct the project. Numerous Cypriots ensured the project’s success like Christos Gregoriou, Christophis Polycarpou (see an example of his work in Smith page 46), and museum professionals like Porphyrios Dikaios.

Given the context of imperial competition and the lead up to WWII, Western scholars in the Eastern Mediterranean were seen as regional specialists and often recruited to spy for their governments. Project members like McFadden, John Franklin Daniel, and the project’s architect, Dorothy Cox, moved seamlessly between academic and espionage circles for the Office of Strategic Services, a predecessor to the CIA (see Reeves page 86). McFadden employed his personal yacht, the Samothrace, to shuttle operatives around the Mediterranean.

1956–1962: el-Jib/Gibeon

(Palestinian Territories)

Excavation at el-Jib (the Biblical Gibeon) uncovered an Iron Age city (700–600s BCE) with massive city walls and a complex water system. The project, directed by James Pritchard, was celebrated for the discovery of an extensive winery and decorated jar handles that shed light on political and economic life in ancient Judah (see Herrmann page 38).

Mentored by William Albright, James Pritchard became a leader amongst the second, more critical generation of Biblical archaeologists. Gibeon, where “the sun stood still” for Joshua’s siege, provided a chance to investigate the accuracy of the Hebrew Conquest of Canaan described in the Old Testament. Although Albright considered the conquest confirmed by pre-WWII research, the question was hotly debated by scholars in the 1950s and 1960s.

Howard Pew, president of the Sun Oil Company (later SUNOCO), personally financed the Gibeon excavation. A staunch Presbyterian, he was one of many wealthy American philanthropists who funded archaeological activities that might support scripture.

As before, the project relied on the labor and skill of many local residents, in what was then Jordan (now the Palestinian Territories). In his memoir, Pritchard described being especially indebted to Asia Halaby, a Palestinian aid worker who ran a support center for refugee women. She acted as intermediary between Pritchard, the workers, and the Jordanian Government, as well as excavating, cataloging, and providing medical services.

1962: Biblical Archaeology Section Created and Beth Shemesh Materials Purchased

After the successful expedition to Gibeon, Museum Director Froelich Rainey announced, “given the Hebrews and Greek impact on Western civilization” it was only natural that a new Biblical Archaeology section in the museum be created. James Pritchard was appointed as head curator and hired to teach as a professor in the Department of Religious Thought (Museum Bulletin 1962 [5]:1).

In the same year, the collections were expanded to include purchases from Haverford College’s 1928–1933 excavation of Beth Shemesh (Ain Shems, Israel). The excavation was directed by Dr. Elihu Grant, a Biblical Literature professor from Haverford, assisted by the Museum’s Clarence Fisher and Alan Rowe.

1964–1967: Tell es-Sa’idiyeh, Jordan

Pritchard turned his attention to the central Jordan Valley next, where there had been little excavation conducted. Part of this neglect among Western scholars stemmed back to the British Mandate period. Corbett (2014) has argued that the territory of Transjordan was delineated in opposition to Palestine, defined negatively as belonging to the inferior neighbors of the Biblical Israelites. Nelson Glueck, American rabbi and archaeologist, all but cemented the same outlook in his extensive mid-century survey of Jordan.

Tell es-Sa’idiyeh had been previously documented and identified by Glueck and Albright variously as Zaphon or Zarathen of the Bible. Pritchard himself did not clarify the name but was drawn to illuminating the history behind Biblical verses, which described the valley as once densely occupied. He was intrigued how such a prominent mound in a strategic location became “forgotten.” Over two seasons of work, the expedition recovered the remains of an urban settlement and extensive cemetery spanning the Late Bronze to Iron Ages (1250–700 BCE). Burials from the cemetery containing jewelry of precious metals and stones, elaborate bronze drinking sets, and imported pottery highlighted the cosmopolitan culture among the ancient local elite and ties to long distance trade.

Finds from the end of each season were stored in the Jordanian Department of Antiquities office in East Jerusalem. This became a problem in 1967 when the outcome of the Six Day War brought East Jerusalem under Israeli control. After some negotiations Pritchard secured permission from Israel to return the material, but only by way of Philadelphia. Jordan’s half of the excavated finds eventually made their way back to the National Museum in Amman.

1969–1974: Sarepta (Sarafand), Lebanon

Given the Six-Day War, Pritchard turned to Lebanon as a quieter alternative. Lebanon was formerly part of the French Mandate but had gained independence after WWII. This time Pritchard sought to shed light on the Phoenicians, the famous ancient Mediterranean seafarers.

After surveying many sites, he was given permission by the Director General of the Antiquities Service, Emir Maurice Chehab, to dig at Sarafand (Sarepta). Four seasons of excavation revealed a long period of occupation from the 1600s BCE through the Byzantine era (600s CE). The project reached Phoenician levels after the second season, most notably finding evidence for pottery and dyeing industries and the earliest example of a shrine complex in the Phoenician homeland. Sarepta remains one of the most important Phoenician ports and settlements documented.

The quiet Pritchard expected in Lebanon was short-lived. Events of the Jordanian Civil War had made southern Lebanon a new center for the Palestine Liberation Organization’s (PLO) activities. Sarepta’s situation on the coast near the Israeli border placed it in the crosshairs of rising tensions between the PLO and Israel. A 1971 clash happened to destroy the project’s dig house and left Pritchard uneasy about further conflict. The lead up to the Lebanese Civil War in 1975 put an end to the project altogether.

1977–1981: The Baq’ah Valley Project, Jordan

By the 1970s, the Biblical archaeology of William Albright gave way to a more anthropological archaeology. Patrick E. McGovern was at the forefront of this movement in the Eastern Mediterranean when he led the Baq’ah Valley project in Jordan with the Museum’s Applied Science Center for Archaeology (MASCA). Five field seasons comprising geophysical survey and excavation across tells and burial caves uncovered material spanning the Early Bronze and Islamic periods.

Applying what were new analytical techniques, from neutron activation analysis and petrography to scanning electron microscopy allowed archaeologists to trace detailed changes in stone, metal, and ceramic craft industries over time. These methods transformed our understanding of how Transjordan peoples experienced and responded to broader historical-environmental processes like the decline of the Late Bronze Age city-state system.

The Baq’ah project took place 9 miles northwest of Amman at a time when urban sprawl from the capital was rapidly reaching north. Using a mix of remote sensing and hypothesis driven analytics, the project was one of the first to anticipate today’s challenges of creating a targeted and efficient archaeological program amidst modern development. In the field, the project relied heavily on the friendship and labor of the Abu Orabi family of Umm ad-Dananir, on whose land the excavations took place, as well as Palestinian workers from the Baq’ah Camp. Another result of the Six-Day War was that the camp was home to a large population of Palestinian refugees displaced from Gaza and the West Bank.